‘Apple’ and ‘sheep’: of the five words the neurologist asked me to remember the first time I saw him I still remember two. Remember these words, he said to me at the beginning of the exam. And at the end of the exam, about twenty minutes later, he asked me to recite them back to him. The truth is, I had memorised them by silently repeating them to myself throughout the exam. I didn’t mean to cheat; it was a reflex. The reflex of a lifelong panicky tester. Another thing the neurologist had asked me to do was to count backwards by sevens, which made my pulse race because I am also all but innumerate.

In any case, I wasn’t at the neurologist’s because I was having memory loss or any other cognitive trouble. I was there because of something that had shown up on a brain MRI. I’d had the MRI because an audiology test had shown hearing loss in one ear only, the left one. Normally if there is hearing loss it occurs in both ears. I would not have had the audiology test if I hadn’t gone to see an ENT, and the reason I went to the ENT was the occasional pain I’d been having behind either one ear or the other or sometimes both.

We call this an incidentaloma, the ENT told me, going on to explain the term, which in fact I already knew: it had happened to me before that some test had by chance detected an abnormality no one suspected or was looking for. In this case, a tumour in the tissue that covers the brain: an incidentaloma-meningioma. Benign.

We don’t have to do anything about it now, said the neurologist, but we do have to watch it. It’s when these things grow that they can cause problems. But if they do grow it’s usually very slowly.

Right now, the tumour was about the size of a chickpea.

Since then I’ve been seeing the neurologist once a year. Some years he prescribes another MRI. So far there has been no change in the size of the tumour. I’m not really trying to be funny when I refer to it as the chickpea, it’s just how I’ve always thought of it, but every time I do the neurologist laughs. Or a macadamia nut, he once said, musingly. But I stuck with chickpea.

We never did learn the reason for the left-ear hearing loss or for the pain in the back of my ears that had started the whole ball rolling. The ENT thought it might have been from clenching my teeth in my sleep. (The pain was mostly noticeable first thing in the morning.) It still happens at times, but I’ve learned to ignore it.

Meanwhile, the hearing in my left ear worsened, and the hearing in my right ear caught up, or should I say down, with it. Just how bad my hearing was came as a surprise. If I couldn’t always catch every word that was said, I thought the blame lay with the inescapable racket where I live: the big-city traffic; the music blasting in so many public places, deafeningly at the gym; the din of crowded parties and restaurants. It didn’t help when everyone started talking through masks.

I was relieved to get the hearing aids not only because I can now hear better but because I know about the connection between hearing loss and memory loss and other kinds of cognitive decline. I did not want to be one of those annoying people who keeps saying What? or who has to be constantly reminded of all the things they would otherwise forget. And what about those studies that show that people with even mild hearing loss are more likely to develop dementia.

As someone who once never had to write down an appointment or a phone number, I take the inevitable weakening of memory that comes with ageing hard. A common response to I forget is Don’t worry, if it’s important it will come back to you. If this was ever true, it is less and less so as life goes on.

Once, when I was sitting in a park, I heard an elderly man lament to his care attendant, It makes me so sad, how much I forget. And the attendant, a woman who appeared to be getting on herself, said chidingly, Now, baby, why do you have to go and think about it like that? Why don’t you think about how much you remember?

I have noticed, though, that in many cases the memories of young people are as bad as their elders’, most likely the result of their deep addiction to digital life, which I have heard a famous neurologist compare to ‘a neurological catastrophe on a gigantic scale’.

Now that I think of it, it might have been the word for some other hoofed animal, not ‘sheep’ but ‘horse’ or ‘goat’. This happens. You remember something promptly but on only a little reflection you begin to have doubts. And the harder you try to remember it, the more your doubts grow.

My aunt Gilda, who lives in a senior housing complex, has just turned 89. Her mind is still sharp, though even with hearing aids she can get things wrong. When I said ‘five words’ she thought I said ‘five wounds’. Her memory is pretty good – better than that of many others her age.

You brought me tulips last time, too, she says, as she peels away the florist’s wrap. And maybe they weren’t tulips, maybe they were daffodils, but she is surrounded by neighbours who would not remember if you had brought them anything last time, or perhaps even that you’d visited at all.

Gilda is not her real name (though it does suit her), and she is not really my aunt. I was told to call her aunt to make it seem like she was more family than just family friend.

She is the family friend I sometimes went to live with when my mother had trouble remembering she had a daughter.

Gilda makes me think of Dolly Parton’s girlhood story, about the town tramp, a woman Dolly’s mother told her was trash, but who to little Dolly was so pretty that she thought trash was what she wanted to be when she grew up too.

Though they were friends, ‘tramp’ and ‘trash’ were words my mother sometimes used to describe Gilda behind her back. And though I knew better than to say it out loud (and not that I had to), I wanted to look just like Gilda when I grew up. Oh, the marvel of her piled-up blonde hair – her termite mound, my mother called it – adorned with a butterfly bow on the front. She put on her face every day, whether or not she planned to go out. Lipstick and blush, eyelashes so long and thick and stiff they made me think of black pipe cleaners. Her bust was the biggest of any woman I knew. She wore sweater dresses with cinched belts, and tall high-heeled boots. Layers of chunky jewellery announced her appearance with as much jangling as Marley’s ghost.

She still wears lipstick, but now I see something that didn’t used to be there before – I would’ve remembered, I think, those red smears on her teeth. Once, after I hadn’t seen her for many years, I met her at a diner for lunch. When I arrived and saw her sitting in a booth I got a shock: her bust was gone. I had just time to think cancer when I saw that her breasts were still there, below the table line. These days, instead of sweater dresses she wears sweatsuits, and her breasts loll on her waist.

Her eyes, always her most beautiful feature, are beautiful still. Like forget-me-nots, as she’d say in her preening moments: flecked gold around the pupil inside a ring of hot blue. She used to be notorious for batting them and for what was called her come-hither look. The trace of that look that has stayed with her into old age I think of as beseeching.

Gilda has a beau, or so she likes to refer to him. She jokes about robbing the cradle, because he is twelve years younger. But it’s really only a game they play; she and he are just friends. Widow and widower. They sit in lounge chairs side by side on her patio like any old folks. There have been Covid deaths in the complex, as well as deaths from other causes, including two suicides, and varying degrees of mental and physical decline have been seen among numerous residents, but these two seem to have come through the pandemic all right. (Better, frankly, than some high schoolers I know.)

How can you wear those things? he says. He had once been prescribed a pair of digital hearing aids but he could not get used to them. No way, he says, not for me. You hear things – you hear everything! I’d take a piss and it sounded like glass breaking. I kept getting spooked, thinking someone was walking up too close behind me. And I’d get these weird clicks sometimes, too, like dolphin speak.

Oh, you, Gilda says, lightly smacking his arm.

Seriously, he says. Who wants to hear everything? Half of what goes on out there, you’re better off deaf.

The grass growing, the heartbeat of the squirrel, to hear such things – ‘that roar which lies on the other side of silence’ – would be too much for us, it would destroy us, George Eliot said.

According to the beau, bad hearing was something the good Lord sent you as you got older to humour you.

You ask someone for directions and they say, That depends on how much spaghetti the chimpanzee put in the pot. And you just have to laugh.

It is true that we’d all cracked up over ‘five wounds’.

The beau recently learned that he has developed atrial fibrillation.

What does that feel like? asks Gilda.

It feels like love, he says.

‘If it was important, it will come back to you.’ Maybe, maybe not. What I want to know is why so much that is unequivocally not important comes back, and why it comes back at the particular moment that it does. I’m not talking about the Proust effect, that glorious blooming into florid life of a past experience that some chance sensory stimulant can inspire. I’m talking about putting away groceries when out of nowhere there floats into my head LG & JS 4 EVER, which was what someone had used a red pen to carve into the back of the seat of the desk to which I was assigned in second grade. It’s the detail that amazes me: the exact crooked shape of the letters, just how much the J slanted to the right, the grain of the wood – indelible, but why? I didn’t know LG or JS. Nor can I remember anything else about that room, such as which classmate sat in that seat in front of me every day. And no intense, poignant childhood episode drenched in beauty and nostalgia arose next. My mind flashed on the image, was momentarily stymied, and moved on.

As memory fails, imagination steps in. It took me a while to realise that what Gilda was doing in the stories she sometimes told about the past was filling in the blanks with things she made up. What I couldn’t tell for sure was when she was and when she was not aware that she was doing this. I’d catch her making mistakes but hesitated to correct them, especially in front of the beau – even though, more often than not, having missed too much of what was said, he got lost, tuned out, and started to nod.

She’d been married twice, but she couldn’t always remember if it was her first husband or her second one who’d done this or that.

It must have been Jack, she’d say. Let’s say it was Jack.

Certainly it made no difference to me. The point was for me to listen, not to set the record straight. For whom would I be setting the record straight? And aren’t we all unreliable narrators of our own lives? I see in her the little novelist that sits in each of us busily working to arrange experience into story. The idea that a human life isn’t like a novel, that there is no plot, no narrative arc, that our memories can’t be relied on for shit, and that everything depends on how much spaghetti the chimpanzee put in the pot – this the human heart will not have.

Married twice, but no kids. When I was old enough to understand, I was told this was because of something that Gilda had done, or that had been done to her, back in the days when abortion was illegal. She’d been just a kid herself then, and unwed, and turning to an angel maker had seemed the right thing to do. She couldn’t know it would become the great sorrow – or, as she put it, the tragedy – of her life. You might think this would have made her a person in favour of legal abortion, but in fact it did the opposite: she is a pro-life fanatic.

The death of her second husband when they were both still middle-aged left Gilda with a deep fear of growing old alone. Even before the lockdown, many in her housing complex were known to be living in isolation, and she could name several – mostly women – who’d ended up dying with no friend or relation nearby. Besides the beau, she has made friends with some of her neighbours, but she clings to me as someone who, unlike any of them, is a link to her past.

She was horrified to hear that my mother had died alone. In her last years, she had become more and more withdrawn, leaving the house only when absolutely necessary, refusing to answer her phone. All attempts to get her to socialise were met first with weariness, then suspicion, and finally rank hostility. Why couldn’t everybody just leave her be? Days, and later weeks, would pass without her even talking to another person. The people next door noticed that, though they were sure she was home, her lights remained off for a whole weekend.

That’s how we learned she was gone, I told Gilda. But when I saw how shaken she was, I regretted having spoken.

This conversation took place the time we met in the diner, well after she had been widowed but before she moved into the senior complex. I’d been surprised to hear from her. Though we didn’t live far apart, it had been so long since we’d been in touch – decades, in fact – that I would have been far less surprised never to hear from Gilda again.

But we really were like family: more than once that day – and innumerable times since – she reminded me.

Your mother was so kind, she said. She felt sorry for me. It wasn’t what you thought, that she was dumping you on me. Not that she wasn’t grateful for a taste of freedom now and then. She was so young when she got pregnant and being a single mother was no picnic. She didn’t want you around your father and his new girlfriend – can’t blame her for that. She needed to find a new man, and how was she going to do that if she didn’t go out? And it’s true that she had lots of dates, but didn’t she deserve to have some fun? And it made me so happy to have you, I kept begging her to let you spend more and more time at my house. It wasn’t that she didn’t want you, or that she ever neglected you. It’s just that I got so depressed thinking how I could never have a child of my own, and she wanted to help me. And it did help. Nothing made me happier than when I had you in the house, especially when you stayed over, and I could pretend you were really mine.

This is how she remembered it.

Speak of pretend, it was on the way to meet her that day that there surfaced something that had been buried a long time, a fantasy I used to have, that Gilda was my real mother. (How I’d ended up with the mother I had was a detail I was content to leave vague.) This was at the height of my infatuation with Gilda. Before Jack – and we can definitely say it was Jack – ruined everything.

According to several articles I’ve read, more than a year of pandemic stress and social isolation has affected many people’s memories. Complaints of opening a closet or cabinet door and not remembering what you were looking for, turning on the phone and not remembering with what intent. Some say they’ve been unable to recall past experiences, or how to do things they once knew how to do perfectly well.

I haven’t noticed that I’ve become more forgetful myself, but in my mind, at least, there will always be a connection between the pandemic and my hearing loss. And since I got the hearing aids, though I can’t imagine what connection there could possibly be, scenes from the past keep flashing through my head in a way I can’t recall happening before.

I don’t want to go to Aunt Gilda’s anymore, I said. But I didn’t say why. And when my mother pressed me I said, I don’t like Jack.

Why not? she said. What don’t you like?

He breathes on me funny, I said. And my mother laughed.

Don’t be silly, she said. You know how she feels about you. You’ll break her heart if you don’t go see her anymore.

I don’t want to go.

Look, my mother said. You said you’d go, she’s expecting you, and you can’t just change your mind now just because you’re in a mood. I don’t get you anyway. I thought you loved it there.

How do men know that you’ll be quiet. Because they do know that. You won’t tell. You won’t throw that bomb. You won’t bring the sky down on everyone’s head.

And tell what, exactly? He breathes on you funny. What was that supposed to mean? He was just smelling your perfume.

He was just dusting lint off your dress.

He was just giving you a big hug because he was so glad to see you.

He was just teasing, seeing if you were ticklish.

He was just trying to warm you because the radiator was broken and the room was so cold.

And the truth is, none of this was the real problem. He wasn’t hurting me, Jack. He didn’t actually scare me. I locked the door before I went to bed. I could handle Jack.

What I couldn’t handle was the sadness – the immense sadness and pity that I felt for her. What I couldn’t handle was being the cause – however innocently – of Gilda’s humiliation. My mother already looked down on her. She wouldn’t blame Jack alone, she’d blame Gilda too – she’d blame Gilda more, I thought. After all, Gilda was the one who was supposed to be taking care of me.

And whom would Gilda blame? She who was so vain. I had learned by then that there were limits to the love of grown-ups. And now I grasped, without fully comprehending, that the whole situation was even more complicated because Jack was a cop.

If he hadn’t grabbed you when he did, you would have got hit by that car.

The trauma of the pandemic and the long solitary confinement of lockdown did much to increase Gilda’s fears. When, after our first visit in more than a year, I leave her with the beau snoring at her side, she doesn’t have to say anything, it’s all in her eyes. Beseeching. Forget me not.

Unlike the beau, I like getting messages from the dolphins. And I like how, after they’ve been recharged, and as you insert them, the hearing aids emit a brief welcome-back jingle. It’s true that, until your hearing adjusts, ordinary sounds can be startling. Chewing and swallowing. Other people chewing and swallowing. Toilet flushes like Niagara Falls. The explosion of a lighted stove.

The audiologist told me about a man who was plagued by the voice of his dead father speaking through one of his hearing aids. Angry, like he’d always been in life. Telling his son what he’d always told him. That he was no damn good. That he would never amount to anything. That he’d driven his poor mother to an early grave. Constantly cursing him, chewing him out.

She stole you, is what she did. She stole your affection, my mother said. She seduced you with everything she had. Next to her I was always the mean one, because I wouldn’t give in to your every little whim like she did. And you thought she was a goddess. If it was up to you, you’d have spent every minute of the day with her. And she was one of those women who treat girls like they’re living dolls, always dressing them up and playing with their hair. You’d come home looking like a tramp. She teased your hair and sprayed it stiff, and she put lipstick and nail polish on you, and drowned you in April Violets. I could smell you before you even came through the door. The first thing I made you do when you got home was take a shower. But worst of all was the time she asked if it would be OK – since, according to her, it was like you had two mothers – if you could call her Mom. I remember you thought it was a great idea. I thought she was out of her mind. That’s when we decided you should call her aunt.

This was how she remembered it.

Once, around the time I turned thirty and was living in a city far from the one where we’d known each other, I ran into Jack. An outdoor holiday market. The hot chocolate stand. He was with his second wife, and they were in town to visit her parents. The three of us walked along together for a few minutes until his wife spied the restroom she had been looking for and asked us to wait for her.

I was the one who put a stop to it, Jack said. I thought Gilda’s thing for you was unhealthy. I’m not saying it was anything kinky, but I thought it was out of control. You might not have seen it, you were so young, but she wasn’t in such good shape then. She never did have the best judgment. Now it was like she was living in her own make-believe world. It was partly my fault, because I’d finally convinced her that we should try to adopt, which up till then she’d resisted. We had an interview with a guy at the adoption agency, and he said Gilda didn’t seem stable enough to adopt a child, and that’s when she really lost it. She truly believed she could have you, that she could get your mother to give you up. I didn’t like going behind her back, but I told your mother that it had to stop. She’s your daughter, I said. She belongs with you, not us.

We watched as Jack’s wife came heading back towards us. Jack was holding a cup of hot chocolate in each hand. I remember Gilda telling me that it took a strong woman to be a policeman’s wife, especially if he worked in a big city. But Jack was about to retire now.

Not that I didn’t miss you, he said.

I missed you too, I said. For a time, he was like a father to me. The only father I had. We really were like a family. Beautiful Gilda, beautiful Jack, and me. He really did save me from jumping in front of that car.

Now that we’re no longer stuck in corona time, that everlasting present where the days all seemed to bleed into one another, everyone is looking ahead. Places to go, people to see: everyone is full of plans.

But already you hear words of nostalgia about the pandemic. As in a news programme I saw. Hospital staff who recall the brutal intensity, how they’d never known a greater sense of purpose, or camaraderie, and how, like soldiers in wartime, they’d never felt more alive. People who discovered blessings in lockdown, in restricted routines that forced them to reassess their sense of values and how they should live. Some say they would not have wanted to miss the awesome feeling of living through a historic moment, of bearing witness to a once-in-a-century event. The cacophonic evening celebrations of healthcare workers. The twenty-dollar bills in the tip jar. The hand-sewn masks and the home-baked bread. The purer air. The calm of abandoned streets.

That everything that was and is no more is to be mourned is an unsettling idea, but what other explanation can there be for the persistence of this kind of emotion? And it’s this yearning, I think, that is partly – perhaps even mostly – responsible for why we get so much wrong, for why memory is so easily overruled by fiction, and why it can be so hard, no matter how we struggle, to get at the truth of our lives.

Iwanted to try an experiment: find a bottle of April Violets, which I haven’t smelled since girlhood, and see what happened when I smelled it again. I couldn’t recall seeing it on sale anywhere lately, but then, since I haven’t worn any kind of scent in a very long time, I hadn’t looked. What with the lockdown, I wasn’t about to go searching in stores, but I figured I could order a bottle online.

But it turns out the original fragrance no longer exists. The company that made it discontinued it some years ago and replaced it with another, also called April Violets, a change that has been met with considerable disappointment. Don’t be fooled, customers warn. It is not the same. It is not the perfume of old!

According to several complaints, the new brand not only doesn’t smell as good, it is also not as strong. It does not seem to have occurred to these customers that in fact the matter might not be with the scent but rather with their sense of smell. Hearing, vision, sense of smell – all are known to grow weaker with age. (Loss of smell: now thought to be another possible herald of dementia.)

Those too young ever to have known the original April Violets appear to be happy with the new one. Not that I was tempted to order a bottle. Needless to say, for the experiment to work, only the perfume of old will do.

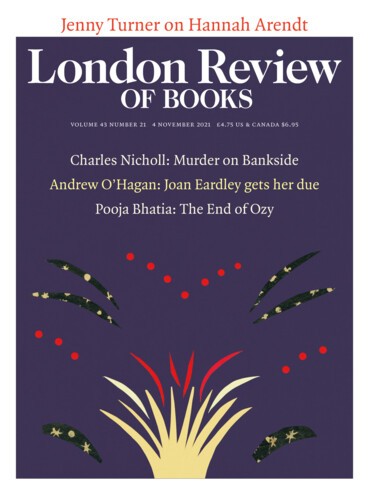

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.