In the mid 1970s , Iran started buying nudes. Some were abstract nudes, such as Willem de Kooning’s Woman III, with her yellow hair and emphatic yellow breasts and an expression that suggests some bemusement at de Kooning’s ‘melodrama of vulgarity’. Some featured nudity as part of a mysterious mise en scène, as in Francis Bacon’s triptych Two Figures Lying on a Bed with Attendants, in which a pair of naked men lie on a peculiar, possibly therapeutic bed. Observers on each side – one suited, one nude (both Bacon’s lover George Dyer) – keep company with animalistic figures. Others were just-for-the-sake-of-it nudes, such as Gabrielle avec la chemise ouverte, one of Renoir’s ‘problem nudes’, which shows Gabrielle Renard, his wife’s cousin and the family nanny, with her sheer blouse open to the waist. All of them were bought for a new state museum, which opened in 1977 as the Tehran Museum of Contemporary Art.

The scheme to create a world-renowned museum of modern art was closely connected to Iran’s political and economic position. While US and European economies faltered, Iran’s soared, buoyed by high oil prices. When Henry Kissinger entreated the shah to freeze oil prices in 1975, he refused, and later cited the US government’s ‘threatening tone’ and ‘paternalistic attitude’. It was time, he argued, for the oil-rich nations of the global South – countries such as Iran, Venezuela, Algeria and Iraq – to resist economic domination from abroad. US intelligence noted that the shah’s ambitions for Iran to ‘become politically and economically co-equal with England and France before the end of this century’ were ‘well-known’.

These ambitions informed Iran’s cultural policies. A country seeking to upend historic power relations needed institutions that rivalled those of its old colonial foes, and the circle around Empress Farah Pahlavi believed that Tehran should have a grand national museum on the scale of the British Museum or the Louvre. In her account of the museum’s formation, Iran Modern (2018), Pahlavi writes that the idea occurred to her in the late 1960s, when a young woman painter complained there was nowhere in Tehran where artworks could be permanently displayed. Pahlavi asked her cousin, the architect Kamran Diba, to come up with a design. He planned the building around a central atrium, which spirals below ground like an inverse Guggenheim. The galleries overlook courtyard gardens, following classical Persian design, and Diba also drew on Persian architecture to create towers shaped like badgirs, or windcatchers. In the desert these provide ventilation; in the museum they allow light to stream in.

A curatorial delegation arrived in New York in May 1975 for the first round of acquisitions. They bought Jackson Pollock’s Mural on Indian Red Ground; several Picassos, including Open Window on the Rue de Penthièvre in Paris; and de Kooning’s Light in August. In the months that followed, these were joined by a number of Rothkos and Alexander Calder’s Orange Fish. The curators had been instructed to purchase art from Impressionism to the present day, so they acquired Monet’s Giverny haystacks, village and garden scenes by Pissarro and Vuillard, Toulouse-Lautrec portraits, paintings by Van Gogh and Magritte, and a few more difficult works, such as James Ensor’s Mariage des masques.

Paintings that documented the West’s preoccupation with the East were a productive theme: Matisse’s mysterious Persian Woman; Gauguin’s Still Life with Japanese Print; a photograph of Edward Lane in Persian costume; André Derain’s L’Age d’or, a pointillist scene of nude women in an unspecified exotic setting. There was something extraordinary about the notion that the museum might bring these Orientalist visions to Tehran, turning the Eastern subject into the viewer. And although most writing on the state collection focuses on Western art, the original idea was a universal museum, one that challenged the categories of ‘Eastern’ and ‘Western’, and displayed Iranian contemporary work alongside international artists. As the art adviser and former curator at the Tehran museum Roxane Zand put it, this was a rare instance of ‘a major institution actually reflecting a reverse process, a reverse colonialism or reappropriation’.

Some of the Iranian contemporary artists whose work the museum collected had lived abroad most of their lives and had built their reputations through the international art market. Although their inclusion was central to the museum’s concept, they are peripheral to Donna Stein’s account of her time as an adviser to Pahlavi. The painter Bahman Mohases, whose work is in Tate Modern’s permanent collection, is mentioned fleetingly (he was ‘known to be homosexual and therefore despised by the Islamic Republic’), while the sculptor Parviz Tanavoli is remembered for giving a lecture on ‘art in a rapidly industrialising society’. Stein writes that she felt herself to be ‘a feminist in an all-encompassing Islamic cultural environment’ and still has complicated feelings about Iran and Iranians, whom she describes at points as ‘small-minded’, ‘under-educated’ and essentially insular (‘embedded into their nature is the idea that they should never trust anybody but their own family’), with the exception of a special few, like the ‘young Qajar prince’ who invited her to fly down to his ‘fabulous Hollywood-style playboy mansion in Isfahan’ for ‘an unexpected exercise in debauchery’. Stein was friends with many Iranian women artists but has little to say about their work or lives. (One exception is Monir Shahroudy Farmanfarmaian, who moved to New York in the 1940s, and whom Stein knew from Manhattan art circles.) She only met Pahlavi herself a handful of times in Tehran, as the grand opening approached.

As Pahlavi gained a reputation as a patron, she began to acquire significant new works through judicious social encounters. She met Henry Moore at a Downing Street dinner in 1976, and was invited to Hoglands, his home and studio in Hertfordshire. During her visit she impressed him by correctly identifying a wood carving as a Miró, and he wrote soon afterwards to offer her ten major pieces. Four of his sculptures eventually came to Tehran, including two massive bronzes that have reclined in the museum gardens ever since.

Pahlavi made overtures to Andy Warhol through the Iranian ambassador to the UN, Fereydoon Hoveida, a Sorbonne-educated writer and painter who often entertained artists. Warhol was a regular guest at his residence on Fifth Avenue, which he nicknamed the Caviar Club, enjoying the food and the opportunities for gossip. Elizabeth Taylor was at that time involved in ‘a highly complicated romantic relationship’ with Ardeshir Zahedi, the Iranian ambassador to Washington, and Warhol was able to tell friends that Zahedi ‘was getting nervous about her getting serious’, perhaps, he suggested, because ‘she can’t convert to Moslem … she’d never make a movie again, right? God, life is really hard. I mean, Elizabeth finally met Mr Rich Right and she can’t marry him because she’s the wrong religion.’

Warhol flew to Tehran in the summer of 1976. At the airport, he was ‘greeted by a dozen little girls in gold brocade’ with pink roses pinned to their lapels. ‘This is like Imelda Marcos arriving in China,’ he said to Bob Colacello, who travelled with him. Warhol holed up in his orange-on-orange room at the Hilton, eating buckets of Imperial Gold caviar and complaining that international calls had to be booked in advance. When he was finally coaxed out, he went to see the crown jewels. ‘Gee, this was the best time we had in Iran. Or anywhere.’ Pahlavi had a sitting with him at Niavaran Palace. He took her Polaroid portrait on a Bigshot camera, with only one member of her entourage present.

The modern art museum was only one among many projects intended to make Iran a cultural hotspot and improve the monarchy’s reputation in the West. Pahlavi commissioned biennales and art festivals, founded a network of museums, and sponsored domestic opera and ballet companies, as well as theatre groups in Europe. Ted Hughes and Peter Brook wrote an experimental play, Orghast at Persepolis, merging the myth of Prometheus with Aeschylus’ The Persians, which was staged at Persepolis as part of the Shiraz Arts Festival. Subsidised in part by the Iranian government, actors from twelve different countries performed entirely in ‘Orghast’, a language invented by Hughes and described by a critic as ‘virile and austere, yet touched with pity and human suffering’. None of this provoked a significant reaction, except a performance called Pig! Child! Fire! by a Hungarian theatre troupe, in which the actors were claimed (incorrectly) to have copulated openly in the grand bazaar of Shiraz.

By the late 1970s, however, political discontent among Iranian students, both inside the country and abroad, was growing. The Carter administration’s inconsistently applied human rights policy emboldened Iran’s leftists, Islamists and Marxist Islamists, who opposed the shah’s authoritarian tendencies and his brutal treatment of political prisoners. They complained that the Pahlavis were ‘Westoxified’, removed from the concerns of everyday Iranians. The empress was an easy target, although not the best one. The shah’s twin sister, Princess Ashraf, was the force behind Iran’s top-down state feminism: she ran the Women’s Organisation of Iran and headed the UN Commission on the Status of Women. As Iran’s leading state envoy on women’s affairs, she espoused a couture feminism for a country where only 50 per cent of women were literate. At one of her balls in New York, fifty Iranian women arrived in matching taffeta gowns from Saint Laurent’s ‘Jewel Collection’, each in a different colour.

Pahlavi’s cultural diplomacy and frequent international trips exposed her to the rising anger of the diaspora opposition movement. In 1977, protesters in ski masks descended on a lunch event she was hosting at the Pierre, disrupting her speech on women’s rights. She recovered quickly, noting that her freedom to give such a speech was a sign of progress. Everyone clapped. How could they not? But the incident led to awkwardness among her artist friends, who began to wonder how closely they wanted to be associated with the regime. Warhol was more dispassionate, ignoring petitions by Kate Millett and Allen Ginsberg urging him to abandon his commissions from Tehran. In 1976 he had agreed to do a cover of Carter for the New York Times magazine (‘It’ll get the art world intellectuals and the liberals in the press off our backs about this Iran thing’), but he kept nervous watch over the portions at the Caviar Club as they dwindled from bowl to blinis, convinced they were a barometer of political turmoil.

When the royal couple fled Tehran in January 1979, they left the crown jewels behind. ‘I always had in mind the Romanovs,’ Pahlavi said. ‘If this happens in Iran, I never want them to say that we took everything away.’ Renoir’s Gabrielle avec la chemise ouverte had somehow made its way to the shah’s private bedroom and, with similar discretion, it was returned to the state museum. According to Stein, the only piece destroyed in the unrest was Warhol’s portrait of the empress. But other accounts dispute this. Sami Azar, who directed the museum in the early 2000s, recently told an interviewer that the damaged work was a portrait of the fifth shah, Mozaffer ad-Din Shah Qajar, which apparently took a bullet, raising the possibility that Warhol’s picture remains in the museum’s vaults. There seems to have been no move to loot the museum, either in the violent and chaotic early days of the revolution or when Saddam Hussein’s army invaded Iran the following year. Thousands of years’ worth of sculpture, carpets, jewellery, porcelain and painting devoted to the veneration of kings were thus preserved. The huge breadth of the collection has been on display at the recent V&A exhibition, Epic Iran.

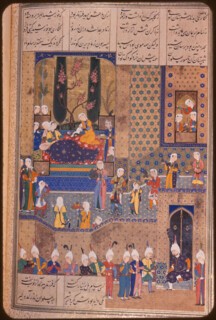

During the Iran-Iraq War, the museum closed and pre-revolutionary artists went underground. The authorities demanded art that served the revolution and which existed where the people could see it, primarily on the sides of buildings. This ‘non-art’, as the sculptor Tanavoli called it, featuring men with keffiyehs and beards, martyrs in combat uniforms and ghoulish Uncle Sams, overwhelmed Tehran. By 1990 the war had ended and a decade of reconstruction was underway, during which the revolutionaries were forced to confront Iranian society’s rejection of their pan-Shia ideology. They produced war cinema that no one watched, films that state television was obliged to broadcast at 3 a.m. In 1994, the government put de Kooning’s Woman III up for sale. It was sold to the American billionaire David Geffen, and the proceeds were used to buy pages of the Houghton Shahnameh, a particularly magnificent edition of the Persian Book of Kings, that had been taken apart and sold as single leaves by a collector in the 1970s. The purchase satisfied nobody. Some complained that the clerics hadn’t purchased a religious text; others asked why Iran couldn’t have both its national epic and de Kooning. No one spoke of selling from the collection again.

The Iranian artists who emerged during the 1990s were influenced by the kitsch visual culture of the revolution and by the new political contradictions: public façade v. private reality, the randomness of what was banned and what permitted, the flow of women into the workforce and their dispossession. In 2001, I visited the artist Khosrow Hassanzadeh at his basement studio in Tehran. I was interested in his tall silhouette paintings of chador-clad women, their forms suggestive of coffins, and his silkscreens depicting the victims of a serial killer who had targeted prostitutes in the shrine city of Mashad. The silkscreens were inspired by Warhol and the bold colours seemed to distinguish the women from their mugshots (the only images he had to work with). Hassanzadeh had studied in the private underground art school that one of the curators of the museum when the shah fell, Aydin Aghdashloo, started after the revolution, and went on to produce a series called Warhol Saved Me.

Around the same time, President Mohammad Khatami, a moderate who ordered the ‘beautiful-making’ of Tehran and launched what he called a ‘dialogue among civilisations’, appointed Azar as the new director of the modern art museum. While taking care not to offend too many clerics, he put on ambitious shows, such as the British sculpture retrospective in 2004, building links with other institutions. He even dared to display the Bacon triptych, although minutes before the opening the police arrived and removed the central panel. During Khatami’s tenure dozens of smaller commercial galleries opened, showing work by contemporary artists (at one point there were more than five hundred galleries in Tehran). There was a wave of enthusiasm for visual art, which like cinema and theatre, carried on a conversation that might have been conducted by political parties or human rights organisations, had they been permitted. The harrowing paintings of Delara Darabi, for instance, who was sentenced to death in 2006 for a crime committed by her boyfriend, were shown at a prominent Tehran gallery as part of an unsuccessful international campaign to secure her release.

Although Khatami formally altered almost nothing, the atmosphere of his presidency loosened the regime’s doctrinaire hold on public space. Alarmed, the clerical establishment backed as his replacement the populist Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, who revived the revolution’s radical philistinism. In 2009, Iranians angry at his re-election revolted. Their protests grew into the largest mobilisation since the revolution, which was put down with great ferocity by the security forces.

The final section of Epic Iran at the V&A focused on the responses of Iranian artists to the last thirty years. The Iran-Iraq War and the flashpoints of violence that followed pushed many towards film and photography, in an attempt to challenge the state narrative of the recent past. The artist Shirin Neshat has said that her discovery of an irreversibly altered country on her return to Iran in 1990 transformed her life and work. Her installation, Turbulent, counterposes two performances: on one screen a man sings a track by a famous Iranian musician in front of an audience; opposite, a woman in what could either be an executioner’s hood or a headscarf, stands mute before an empty hall. The day I visited the exhibition two young men recently arrived from Iran watched the male side of the installation appreciatively, until I coughed and tilted my head towards the silent video. Eventually the man’s singing ended, and the woman’s began, her voice breaking out like a sudden shriek.

Women were banned from singing in public after the revolution, as the clerics promoted a notional ideal of womanhood that bore little resemblance to the lives of most women, especially those in rural areas who largely worked outdoors. Mitra Tabrizian’s Tehran 2006 is a staged photograph of an everyday urban scene transposed to a wasteland on the fringes of Tehran. Under a mural of Iran’s last and present supreme leaders, a young couple stroll, a mother takes her child home from school and an old man clutches a loaf of bread. A ghost-like woman in a villager’s white chador lurks in the background. The figures appear frozen in time, unaware of one another and of their surroundings. Iranian art, particularly cinema, is often praised for exploiting the aesthetic subtleties demanded by strict censorship laws, but Tabrizian isn’t interested in this but rather in the flattening effect of state ideology on people who don’t have recourse to or interest in visual arts.

For women in Iran, obliged to wear the manteau (the utilitarian overcoat mandated by the revolution) and head covering, dressing means navigating narrow definitions: conformist, rebellious or – the elusive ideal – modest yet original. The young woman in Shirin Aliabadi’s photo-portrait Miss Hybrid #3 shows no such ambivalence about her appearance. She has fashioned herself to look determinedly Western. A perfunctory headscarf is pushed back over a wave of platinum blonde hair and two fake blue eyes look out over a surgically taped nose. She blows a large, defiant pink bubble. Aliabadi, who died in 2018, lived between Tehran and Paris and was taken by the contrast between the images of Iranian women she saw in France and the aesthetics of young women in Iran. ‘I don’t believe that you automatically become a rebel with a Hermès scarf around your neck,’ she told an interviewer in 2013. ‘Ultimately these young women’s concern is not to overthrow the government but to have fun.’

Not all the contemporary Iranian artists included in the V&A exhibition engage overtly with political and social questions. A piece by the artist Farhad Moshiri, Aliabadi’s husband, shows the word eshq – the spiritual love at the heart of Persian Sufi poetry – spelled out in Swarovski crystals (it’s famous to Iranians for its price tag: one million dollars when it sold at an auction in Dubai in 2008). Moshiri’s work often incites a criticism much made of contemporary Iranian art, that it is facile and clichéd in comparison to work produced before the revolution, mindlessly commercial in theme and appearance. The V&A curators chose not to explore whether such artists are representative of a society in the grip of superficiality, or are responding to this shallowness, or something else entirely: complicit in their own exoticisation by creating work bound for a Persian Gulf art market hungry for glitter and uninterested in irony. In the catalogue, Ina Sarikhani Sandmann describes Moshiri’s fascination with ‘global consumerism’ and the ‘commodification of desire’, but he is, I think, a more active participant, his work both lament and enthusiastic submission.

‘Despite international rhetoric,’ the curators claim, ‘Iranian culture, even beyond fine art, travels well.’ They cite the films of Asghar Farhadi and the popularity of Persian food. ‘Travelling well’ is another way of saying that Iranian culture wields soft power. In Iran Modern Pahlavi staked her claim explicitly, claiming to be ‘testament to the influence of soft power to change the fabric of a nation for ever’. Stein wants credit too, for her ‘leadership role’ in assembling the modern art collection. Iran’s chargé d’affaires in London attended the opening of Epic Iran and noted that the embassy had supported the idea of the exhibition for years in the hope that exposure to Iran’s long civilisation would help Westerners ‘better understand’ the country. The V&A director, Tristram Hunt, stressed the significance of the show in the current political climate, saying that sanctions on Iran (which prevented the lending of many pieces from Tehran museums) and ‘militaristic language’ – presumably Trump’s threat to blow up Iranian cultural sites – made the exhibition ‘more valuable’. The Tehran Museum of Contemporary Art, for its part, soldiers on quietly, maintaining the most discreet and attention-deflecting public profile of any major institution. Its first post-pandemic show was a Warhol exhibition.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.