Afew weeks ago, I came across a young poet saying that the book he had been turning to during Covid was Francis Ponge’s Le Parti Pris des choses. (Siding with Things, the translation of the title in the old Faber Selected Poems, is clever, capturing as it does Ponge’s mixture of gentleness and misanthropy.) One of the most winning items in the Barbican’s Jean Dubuffet exhibition, Brutal Beauty (until 22 August), is a pen and ink drawing of Ponge, balding, flat-nosed, grinning from ear to ear, expecting the best from his portraitist. The year is 1947, and artist and model are united against existentialist gloom. ‘People Are a Lot Better Looking than They Think,’ said the poster for Dubuffet’s Portraits show that October. ‘Vive Leur Vraie Figure.’

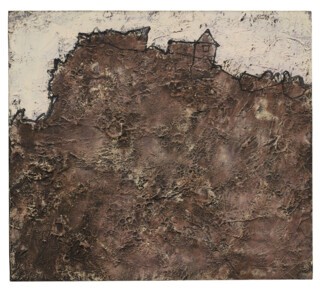

Dubuffet, like Ponge, was essentially a comedian. Look at his Abandoned House from 1952. Banish all thought of catastrophe. Rocks are nice. Ruined houses are pleased to be on their way back to them. Consider the wrinkles and bubblebursts of paint all over the picture foreground as the planet reclaiming its rights at last, maybe suppressing an attack of giggles. Compare Ponge’s prose poem ‘Moss’:

Long ago the advance guard of vegetation came to a halt on the rocks, which were dumbfounded. A thousand silken velvet rods then sat down cross-legged.

From then on, ever since moss with its lance-bearers started twitching on bare rock, all nature has been caught in an inextricable predicament and, trapped underneath, panics, stampedes, suffocates.

Worse yet, hairs grew; with time, everything got darker.

Oh obsession with longer and longer hairs! Deep carpets that kneel when you sit on them now lift themselves in muddled aspiration. Hence not only suffocations but drownings.

Well, we could just scalp the old, severe, solid rock of these terry-cloth landscapes, these soggy doormats: they’re so saturated, it would be feasible.

I grant that, even with C.K. Williams’s version of ‘Moss’ for a guide, it is hard to see a painting like Abandoned House – done at this date, using this range of colour, rubbing our noses in matière – and not think of bombsites and mushroom clouds. A canvas in the same series is called Le Burg dévasté. It doesn’t help that on its first showing Dubuffet accompanied the series with pronouncements on ‘formlessness’ and ‘landscapes of the mind’. I don’t doubt his sincerity as a writer, but I think he consistently misunderstood (or chose to disguise) his paintings’ tone – the level on which they truly affect us. He didn’t see (or wished not to talk about) the power of their lightness.

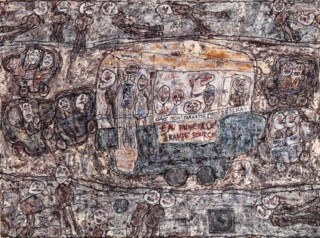

That power is on view throughout the Barbican show, but nowhere more strongly than in the dark room immediately to the right on entry. It contains three paintings from 1961. All are dazzling and full of laughter. The best is the biggest, Paris-Montparnasse. Its scene of obedience on the boulevard is put together, as very often with Dubuffet on form, in a rough and ready grid, compartments shallow as slides under a microscope, people encased in their cars and buses like infusoria, grinning à la Ponge. (Or maybe shrieking.) The overall colour of the picture is a light translucent brown, and the feeling of shit-smear is intensified by areas of pale yellow, red and blue, put on thin and dry and then worked with the brush into a kind of scarified concrete. The contrast with Abandoned House’s bubbling is complete. Dubuffet’s Paris is made of breezeblock. Mind what you touch. The words on the side of the 96 bus are counterfactual: ‘Eau Minérale Grande Source.’ From Vichy, I guess.

A minute or two in front of Paris-Montparnasse is enough to confirm the picture’s sophistication. The least detail of drawing, clumsy and electric as it seems at first sight, is adjusted to the play of colour and the pressure of the free but constraining grid. Look at the man swigging beer inside the bus – look at the chatter of red on his cheek, or the geometry of his nose and beer-arm. You can spot his eye from twenty paces: it is the painting’s still centre. Dreadful – every character in sight (there are 31 of them) is trapped, flattened, rigid with attention to something we’re glad we’re not shown – but happy. Euphoric. They’ve never had it so good.

One of Dubuffet’s preoccupations as an artist was the thin line between vividness and vagueness in perception. His 1954 series of single figures looming out of urban darkness, pressing against the picture edge, gives the idea its purest, most sinister expression: Chevalier de nuit and Intervention, for instance, are apparitions whose indistinctness only makes their proximity worse. They’re characters catching our eye on an ill-lit street. Wearing their rags as a weapon. Paris-Montparnasse continues the train of thought: the shocked individuality of each figure is inseparable from the storm of brushmarks overtaking them – the din of traffic noise, the cold glare of sodium. The picture as a whole borrows its syntax from Cubism: rectangular cell structure, spidery line, overall monochrome, flicker of ‘touch’ wherever there’s emptiness. But in Cubism evenness – this was the claim – came out of coherence, out of a logic discovered in things. In Dubuffet unity is force. People and things are steamrollered into togetherness. That’s the way things are.

There was agreement from early on, among those who cared, that Dubuffet was a major artist, and most likely the last that France would produce for years to come. He stood at the end of a tradition. He had Watteau and Fragonard in his bones, alongside Renoir, Redon, Miró, Dufy. Again, at the level of opinion and self-reflection Dubuffet was undoubtedly sincere in his wish to escape from that inheritance – he spent much of his career pouring scorn on the paintings he saw on the Rive Gauche – but he was no kind of fool: he knew full well that every movement of his brush reeked of tastefulness, learnt precision, delicacy. The Barbican show rightly gives room to the results of Dubuffet’s long effort as collector and propagandist for Art Brut: several galleries are devoted to the paintings and drawings he assembled, done by the insane, the reclusive, the deeply disadvantaged and ecstatic. They may well hold the visitor’s attention in a way no Paris past master is likely to. Dubuffet would have sympathised. Perhaps there were moments in his studio when he looked at the world of non-art with which he had surrounded himself and thought he had a chance of borrowing its honesty and strangeness. But it would have to be borrowing, not counterfeiting. And in practice the borrowing did not take place.

The most difficult thing to decide in Dubuffet’s case, therefore, is what his worked-up lightness and laughter are after, and why the lightness has depth. (It’s a question that comes up with many in the line of French art he inherited. Think of Corot or Monet or Bonnard.) There are some phrases in a poem by Emily Dickinson that strike me as helpful, particularly with Paris-Montparnasse in mind:

Anguish – and the Tomb –

Hum by – in Muffled Coaches –

Lest they – wonder Why –

Any – for the Press of Smiling –

Interrupt – to die –

This could almost be the painting’s script – all the more so because Dickinson’s sardonic moroseness is so leavened by line breaks and dashes, her version of ‘touch’. The French themselves can be more severe on the subject. Democritus, Montaigne tells us, ‘never went out in public but with a mocking and laughing face’. And his attitude is exemplary, Montaigne says, preferable to Heraclitus’ tears, ‘not because it is pleasanter to laugh than to weep, but because it is more disdainful, and condemns us more than the other; and it seems to me that we can never be despised as much as we deserve … We are not so full of evil as of inanity; we are not as wretched as we are worthless.’ Florio’s translation is triumphant: ‘We are not so full of evil as of voydnesse and inanitie. We are not so miserable as base and abject.’

But this, Dubuffet would have thought, moves comedy too close to moralising. (Sartre was a constant bugbear of his. He loathed Sartre’s criticism of Céline.) Real life leaves judgment behind. Laughter is an automatism. The achievement of a painting such as Paris-Montparnasse, it follows, is bound up with its refusal to decide – or to allow its viewer to decide – whether the right attitude in the face of ‘modern life’ is a true Democritean facetiousness, or a kind of astonished compassion. Look at it, the new form of freedom! Look at the babies in their motorised prams! How could anyone – even my lunatics and visionaries – find an idiom to match?

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.