In her new book, Rosemary Hill characterises the achievements of more than thirty antiquaries of the late 18th and early 19th century whose records of mysterious inscriptions, stone circles, monastic chronicles and ruined abbeys, and whose collections of rusty weaponry, stained glass and old ballads, provided new ways by which the past could be recovered – and also, of course, invented. Some of these antiquaries are familiar to architectural historians, others are known only to a few specialist curators of armour or to historians of ancient games or to students of Middle English, but the links between them and their often disparate specialities have never previously been explored. Walter Scott and Victor Hugo feature among the less familiar scholars, and some painters, including Bonnington and Delacroix, make brief appearances. As these names suggest, Hill has much to tell us about Anglo-French relations, present as well as past.

We learn, for example, that the Bayeux Tapestry, after narrowly avoiding destruction during the Terror, began to be treated with more respect and was even displayed in the Louvre when Napoleon was planning to follow the example of William the Conqueror; also that Carlyle’s condemnation of heartless capitalism was prompted by Jocelin de Brakelond’s 12th-century chronicle. But the best example of this dialogue between past and present is the way that the destruction of ancient monuments instigated by the French Revolution stimulated awareness of the ‘génie du Christianisme’. The word ‘vandalisme’, Hill tells us, was first used by the bishop of Blois on 14 fructidor, an III (31 August 1794). The previous year, the royal effigies from the Abbey of St Denis had been transferred to the former monastery of the Petits Augustins on the left bank of the Seine, a depot already filled with historical monuments salvaged by Alexandre Lenoir together with treasures confiscated by the state. It took Lenoir several years to convert this repository into one of the most influential displays ever devised in a museum: the religious and royalist past that the revolution had endeavoured to destroy was given chronological order, an evocative setting and a guidebook that was sentimental as well as informative. Although the Musée des Monuments Français only existed for twenty years, its progeny were manifold. (One offshoot in Paris, the private museum of Alexandre du Sommerard, which in 1832 moved into the half-ruined medieval Hôtel de Cluny, was acquired by the state a decade later, thanks to the efforts of Lenoir’s son, who was responsible for converting it into the Musée des Thermes et de l’Hôtel de Cluny.)

The elaborate tombs of the dukes of Burgundy, which survived the destruction of the Chartreuse de Champmol, were carefully reassembled and restored and placed on display in 1827 in the Guard Room of the Ducal Palace in Dijon. This was the creation of Févret de Saint-Mémin, a local aristocrat who, having earned his living making profile portraits in North America, was appointed director of the city’s art academy by the restored Bourbons. Although now incorporated within a much larger museum complex, it may claim to be the earliest, as well as the most spectacular, surviving museum devoted to the art of the Middle Ages. Hill, however, concentrates her attention on Normandy, which was of special interest to British as well as French antiquaries. In the early 1830s the new Musée d’Antiquités in Rouen was created in the former Convent of the Visitation. Not only did it incorporate the miscellaneous manuscripts and fragments of glass and sculpture and architecture assembled by the great antiquary Eustache-Hyacinthe Langlois but also (for a few years) the antiquary himself, who had long lodged there, often in freezing cold, always in dire poverty, together with his alcoholic wife and unruly children. ‘After his death,’ Hill writes, ‘the museum remained for some time both chronicle and monument of his strange life; the cloister was renamed the Galerie Langlois.’

In 2014, the museum of Bourg-en-Bresse (in partnership with the Musée des Beaux-Arts de Lyon) mounted a fascinating exhibition, L’Invention du passé, in the cloisters of the monastery church of Brou. It was devoted to paintings inspired by Lenoir’s Musée des Monuments Français – works by painters who are very little known to the British public, including Fleury Richard, Pierre Révoil, Henriette Lorimer, François-Marius Granet and Louis Daguerre (famous for his photography but not his paintings). In these works, moonlight on broken stone tracery is a common motif; dark interiors provide a foil for stained glass and for white satin and deep blue velvet. The men must be away on the crusades. Young women are sobbing beside tombs or seated in Gothic cloisters. Most are dressed in the style of 1280, but some in that of 1820, and there are numerous attractive young nuns in timeless habits. Hill illustrates a painting very much in this taste, depicting the Duchesse de Berry as Mary, Queen of Scots, sailing to exile in Scotland after the July Revolution of 1830.

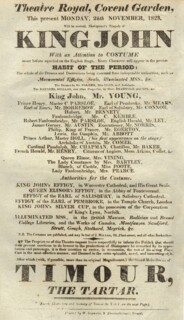

She also documents the many ways in which, on this side of the Channel, the medieval was employed to invest contemporary power with glamour and authority. Among the incisively captioned illustrations is David Wilkie’s painting of George IV in Highland dress – the outfit he wore for his entry into Edinburgh in 1822 (an event that was stage-managed by Scott) – opposite the playbill for a production in 1823 of Shakespeare’s King John at the Theatre Royal, which boasted an ‘Attention to Costume never before equalled on the English Stage’.

The century before Scott’s The Antiquary (1816) saw the burgeoning of a type of antiquarianism about which Hill has less to say. It is well illustrated by Three Hours after Marriage, a farce written by John Gay, with the assistance of John Arbuthnot and the young Alexander Pope, which was performed at Drury Lane in 1717. The leading character, Dr Fossile, has just married a much younger woman (‘the best of my curiosities’) and is unaware that two would-be seducers have moved into his domestic museum: Plotwell, disguised as an Egyptian mummy, and Underplot, as an alligator. I refrain from revealing the outcome but note that the mummy and the alligator, like coins and shells, neatly illustrate the artificial and the natural curiosities studied by the man who inspired the character of Fossile: John Woodward (1665-1728), then a figure hardly less eminent than Newton. Woodward, a highly successful physician, was especially famous for his Essay towards a Natural History of the Earth (1695). He had a great collection of fossils (bequeathed to Cambridge University and now incorporated in the Sedgwick Museum) but his most prized personal possessions included an urn mentioned by Horace in one of his odes and the head of Terence cut in an emerald.

Woodward was also the owner of a Roman shield on which the defiance of Camillus at the siege of Rome was represented in relief. This once celebrated weapon (which was in fact no more than 150 years old when Woodward acquired it) is now largely forgotten – as is the remarkable book by Joseph Levine, Dr Woodward’s Shield: History, Science and Satire in Augustan England (1977), which detected in Woodward’s publications and those of his many enemies the prehistory of palaeontology, geology, archaeology, epigraphy and numismatics. Levine demonstrates that antiquarian preoccupations were stimulated in the early 18th century by excavations of London following the Great Fire. A statuette of Diana, ‘made of brass and two inches and a half in height’, dug up not far from St Paul’s Cathedral was, Woodward thought, important evidence in the debate over whether there had been a Roman temple dedicated to the goddess on the site of the cathedral.

In her first chapter Hill traces the intellectual ancestry of her antiquaries to an earlier catastrophe: the dissolution of the monasteries, which created ruins throughout Britain of a kind that, in John Aubrey’s words, ‘breed in generous minds a kind of pittie; and sett the thoughts a-worke’. In her article ‘English Ruins and English History’, Margaret Aston emphasised how extensive the visible devastation must have been and how powerfully and frequently it generated a sense of nostalgia: ‘And with nostalgia came invigorated historical activity.’ The mainstream of antiquarianism that sprang from this invigoration commenced with William Camden (1551-1623), before proceeding to John Selden (1584-1654) and William Dugdale (1605-86), and on to Thomas Hearne (1678-1735). Hearne was a quarrelsome man, sacked from his job in the Bodleian Library for his Jacobite sympathies. Pope devoted five lethal lines to him in the third book of The Dunciad, adopting Chaucerian English for his purpose: ‘But who is he, in closet close y-pent … On parchment scraps, y-fed, and Wormius hight.’ What could be more ridiculous (even to a Roman Catholic like Pope) than respectfully studying the age when antique statues were hurled into the Tiber and Livy was burned by papal edict, and what could be more pointless and pedantic than investigating a Britain populated by dismal pedestrian monks and friars (characterised in plodding metre: ‘Men bearded, bald, cowl’d, uncowl’d, shod, unshod,/Peel’d, patch’d, and pyebald, linsey-woolsey brothers’)? Hearne, however, was not only a medievalist. He also published an edition of Livy in which he included an illustration of Woodward’s shield, and he defended its authenticity in other publications.

Hill contends that antiquarianism had been marginalised by the mid-18th century: ‘An increasingly secular age felt no inhibition about admiring pre-Christian civilisation and looked askance at manorial records, church monuments, brass-rubbing, heraldry and bells.’ This judgment is confirmed by Pope’s confident disdain for Hearne. It is worth noting, though, that the heroine of his Eloisa to Abelard suffers among ‘spiry turrets’, ‘awful arches’, ‘dim windows’ and ‘long-sounding aisles’, and Pope’s friends were at the very same time erecting castellated eye-catchers and imitation hermitages in their landscaped parks. As Hill points out, such follies grew into major residences and the monastic ruins became tourist attractions.

It would not be easy to maintain that the Gothic held more sway over the poetic imagination than did ancient Greece in the period with which Hill is most concerned – certainly not if we consider the poetry of Shelley or Keats. More often the Gothic was shown in opposition. Stiff tomb effigies, angel corbels, tapestry of hare and hound, and heraldic stained glass feature prominently in The Eve of Saint Agnes but they are associated with the ‘bitter chill’ of winter and with death (even the ‘argent revelry’ in the castle is ghostly and the colours of the glass recall the ‘blood of queens and kings’). It is a place from which young lovers fled – ‘ay, ages long ago’ – whereas it is to Greece that love flees, finds and fulfils itself.

Michael Angelo Titmarsh (alias of William Makepeace Thackeray) informed the readers of his Paris Sketch Book that Jacques Louis David ‘died about a year after his bodily demise in 1825. The romanticism killed him. Walter Scott, from his Castle of Abbotsford, sent out a troop of gallant young Scotch adventurers, merry outlaws, valiant knights, and savage Highlanders’ who ‘did challenge, combat and overcome the heroes and demigods of Greece and Rome’. This was an overstatement that can be qualified by attending to the mythological paintings of, for instance, Prud’hon or Guérin, painted in the first decades of the century, which exhibit such affinities with the poetry of Shelley and Keats.

Nineteenth-century antiquarianism was, however, decisively, and almost by definition, separated from Greek and Roman art and history. It is also striking that there are no medical practitioners among the numerous antiquaries of this period described by Hill, whereas a century before it was not unusual. Collectors of fossils were no longer likely to collect armour, as Woodward had. During the 18th century the study both of Greek and Roman antiquity and of geology and palaeontology diverged and developed into separate and more respectable fields.

Levine, in the conclusion to his study of Woodward, demonstrated that Woodward’s methods anticipated those of the very scholars who would refute his theories, notably Winckelmann and Cuvier. Method could, of course, move from one field to another. In her accounts of the antiquaries Arcisse de Caumont and Dawson Turner, Hill suggests that their earlier interests in the study of geology and botany, respectively, may have helped them to analyse and illustrate the medieval antiquities of Normandy. She also observes that the strong organisational intelligence and meticulous observations of Thomas Rickman, whose Styles of Architecture in England from the Conquest to the Reformation, published in 1812, established terminology still in use today (Norman, Early English, Decorated and Perpendicular), may have owed something – if only its tighter focus on the visual evidence – to his limited education and ignorance of Latin. Rickman, who was also detached from nationalist and religious interest groups, certainly seems to have looked at buildings with the neutrality appropriate for the student of natural history – his subject was the way that architecture evolved, and it is tempting to wonder whether, reading him, it may have become easier to conceive of the evolution of the species.

Some of the more severe scholars described here may have preferred to be regarded as historians or archaeologists rather than as antiquaries, given that the latter were closely associated with fiction quite as much as with truth, and often with the ‘pasticcio’ (which in its original meaning refers to one genuine old object given a false identity by combination with another). John Keble, founder of the Oxford Movement and author, Hill tells us, of ‘the widest-selling book of poetry in the 19th century’, filled his church with miscellaneous old panelling and stained glass from a dozen different destroyed or deconsecrated churches on the Continent. He was supplied by dealers in Wardour Street who also helped to furnish new imitations of ancient structures such as Goodrich Court, built for Henry Meyrick, the great authority on medieval armour, as a substitute for a genuine and much coveted castle nearby. It would have been still harder to disentangle fiction and truth at Abbotsford, where Scott had gathered ‘the sporran of Rob Roy, the keys of the old Tolbooth and Napoleonica from Waterloo’, while the Highland home of the Sobieski Stuarts was a ‘farrago of Tartan, antlers and dubious Jacobite relics … so integral to their pretended place in history’, as claimants to the royal house, ‘that without it they were fatally diminished, snails without shells’. On the subject of credulity (or at least the willing suspension of scepticism) there is the conclusion of Hazlitt’s essay on Fonthill Abbey, published in the London Magazine in 1822, which is consecrated to Richard Cosway, the fashionable miniaturist who had died the previous year:

His was the Crucifix that Abelard prayed to – the original manuscript of the Rape of the Lock – the dagger with which Felton stabbed the Duke of Buckingham – the first finished sketch of the Jocunda [Gioconda] – Titian’s large colossal portrait of Peter Aretine – a mummy of some particular Egyptian king. Were these articles authentic? – No matter – his faith in them was true. What a fairy palace was his of specimens of art, antiquarianism, and vertù, jumbled all together in the richest disorder, dusty, shadowy, obscure, with much left to the imagination (how different from the finical, polished, petty, perfect modernised air of Fonthill!).

The ‘truth’ of Cosway’s ‘faith’ provides a clue. His specimens were by no means only medieval but they prompt us to ask whether enthusiasm for the ‘Age of Faith’ may have licensed an attachment to dubious relics.

Or was it simply that the historian’s imagination required more ignition than legitimate evidence could provide? ‘Abélard’, one of the first entries in Flaubert’s Dictionnaire des idées reçues, concludes with a reference to the tomb Lenoir concocted for Eloise and Abelard, by then transferred from the garden of the dismantled Musée des Monuments Français to the Cimetière Père Lachaise: ‘If anyone explains to you that it is a fabrication [faux], exclaim: “You are stripping me of my illusions” [Vous m’ôtez mes illusions].’ Such illusions were inseparable from the ideals of romanticism, just as their destruction was essential to the realist agenda.

The passages of her book devoted to the gradual understanding of the origins and development of Gothic architecture are Hill’s most significant contribution. As the biographer of Augustus Welby Pugin, she is especially well qualified for this task. The recognition that the cathedrals of Chartres, Salisbury and Cologne are as magnificent and beautiful as the Pantheon or the Parthenon is surely one of the greatest changes in the history of taste. The only comparable episode in recent centuries is the re-evaluation of Italian painting before Raphael. Hill records the excitement over an altarpiece by Jan Mabuse (Gossaert) among antiquaries in the 1790s, but Fra Angelico and Botticelli are not her concern. The rediscovery of the national past is undoubtedly a large enough subject. However, it is worth noting how intertwined these episodes were.

The 15th century in Italy came by 1850 to be identified as the ‘early Renaissance’, and therefore with the rebirth of Greek and Roman antiquity, yet many of the paintings of this period were clearly Gothic, not only in the architecture of their frames but in the graceful curves of the figures. Before these paintings were termed ‘Primitives’ they were often called ‘Christian’; the adjective, as Hill shows, enjoyed some favour as an alternative to ‘Gothic’ in descriptions of medieval architecture. The single most important figure in the rediscovery of early Italian painting in Britain was the artist, scholar and collector William Young Ottley, who had studied the frescoes in Assisi and the earliest of the Baptistery doors in Florence in the 1790s and was also the first British collector to own a work by Botticelli. He was, in addition, a pioneer investigator of the origin and early history of engraving and in his last years, when serving as the discontented keeper of the print room in the British Museum, he applied himself to cataloguing the rubbings of the large engraved plates set into tomb chests and the paving stones of parish churches. These cumbersome records of monumental brass effigies – ‘the great part of which no longer exist’ – had been bequeathed in 1834 by Francis Douce, one of the heroes of Hill’s book. Douce’s ivories and other medieval objects went to Goodrich Court, which was expanded by Samuel Rush Meyrick to accommodate them. It was not until 1850 that a department devoted to British antiquities was established at the British Museum.

Most of Hill’s antiquaries, and all of the British ones, worked outside any established institution. By the 20th century scholars who might be considered their equivalents, including many who were quite as difficult, eccentric and uncouth, had been fully absorbed by museums and universities. Many of us will recall the man in the moth-eaten cardigan, apparently talking to himself as he perambulated the lawn, who had a greater knowledge of his subject than anyone else alive but never finished his book.

Time’s Witness, which records with such verve the steady extension of subjects deemed fit for scholarly investigation two hundred years ago, is published at a moment when much of the curiosity and many of the pursuits it documents are endangered. The insistence on a global perspective, now more or less compulsory in schools and universities, is usually conducted in one language, often extends very little into the past, and seems better designed to buttress than to question contemporary pieties and certitudes. Museums in the UK and the US are sweeping away cases of specimens and reducing the number of curators responsible for old and ancient art and artefacts. Funding is available for ‘interventions’ and installations, whereas cataloguing the antiquities in store is ‘not a priority’ and sometimes is even discouraged.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.