Thomas Becket was not the first archbishop of Canterbury to meet a violent end – Archbishop Alphege was killed by Vikings in 1012 – but he was unique in other ways. Unlike his predecessors, he was not particularly learned and wrote nothing except letters (the 12th-century equivalent of texting), of which 189 survive. He preferred hunting, hawking and fine clothes to the discipline and asceticism of religious life, all of which left him heavily in debt. He didn’t direct his energies to grand episcopal projects like his contemporary Henry of Blois, the wealthy bishop of Winchester, who oversaw the construction of villages, canals, castles, abbeys and smaller churches. Becket concentrated instead on patronising his coterie of followers. Before his appointment as archbishop, he wasn’t even a priest.

The story of Becket’s ascent and his dispute with Henry II form the first part of the British Museum’s exhibition Thomas Becket: Murder and the Making of a Saint (until 22 August). The show opens in 12th-century London, where Becket was born in 1120, or thereabouts, to a Norman mercantile family of rising prosperity. Some pottery, coins and a pair of bone ice skates, supplemented by a manuscript illustration of boys skating and sledging, represent the environment in which the young Becket grew up, but we’re given little sense of the city itself with its diverse population of recent immigrants, foreign merchants, and its notable Jewish community. The young Becket was proud of his roots. An example of his personal seal declares him ‘Thomas of London’ and probably dates from his time in the household of Theobald, archbishop of Canterbury between 1145 and 1154.

Becket’s meteoric rise was remarkable, even in an age when ‘new men’ jostled with leading noblemen for senior positions in government. The presence of these novi homines reflected the increasing importance of legal education, powers of argument and documentary expertise in both royal and ecclesiastical administration. As a young man, Becket managed to acquire enough of these skills to charm his way to the centres of power. His good looks and indefatigable networking helped. At the age of 22, he was described as ‘gentle of manner and sharp of intellect, easy-going and amiable in conversation’. He made his way in royal government at a time when there was little distinction between politics, bureaucracy and diplomacy, and like all literate men in royal service, he had been educated in ecclesiastical institutions, which in Becket’s case meant London, Paris and a year of law in Bologna.

This was no preparation for life as a priest or monk, however, let alone head of a cathedral community that retained a distinctively monastic way of life. If his promotion in 1155 to the position of chancellor (head of the royal administration) to the newly crowned Henry II was unexpected, his appointment, at royal behest, to the archbishopric of Canterbury seven years later was even more so. The first was on the recommendation of Theobald; the second Henry’s own decision. Becket was ordained to the priesthood on 2 June 1162 and consecrated archbishop the following day. Soon after, on receiving papal confirmation of his appointment, he resigned the chancellorship. As one of his contemporaries remarked: ‘From a secular man and a knight, [Henry II] had fashioned an archbishop.’ Becket had jumped the tracks.

The handful of documents on display at the British Museum are included for the iconography of their seals, but they also serve as material witnesses to royal and ecclesiastical administration. Such documents are significant because when Becket and Henry II fell out in 1163 – over the primacy of Church v. monarch – the dispute revolved around what was or wasn’t written down. Henry II sought to limit ecclesiastical privileges, which had expanded under his predecessor, Stephen of Blois (1135-54), and to re-establish royal authority in the kingdom. To do so, it was necessary ‘to recollect and carefully write down’ the ‘ancient customs’ that had governed the law during the reign of Henry I (1100-35). Only in January 1164, after Becket had been bullied into verbally acknowledging such customs – he refused to do so in writing – was Henry II able to pass the Constitutions of Clarendon and limit papal authority in England. Regretting his compliance, Becket soon tried to back out, but the tension ratcheted up with charges that he had embezzled royal funds and denied justice to his subordinates. By the end of the year, Becket had fled England in disguise and sought asylum in the lands of the French king, Louis VII.

Both Becket and Henry tried to enlist papal support, but Alexander III, mired in his own difficulties and also in exile in France, sat on the fence. Here again the question of what was written, proclaimed verbally (sincerely or not) or left unsaid greatly influenced the subsequent course of events. Alexander III told Becket that some clauses of the Constitutions of Clarendon were contrary to Church law, but others tolerable, without being specific or committing anything to writing – in effect, he kept his options open. It has been said that we know more about Becket’s life than any other Englishman of the Middle Ages, but his character and principles emerge much more fully from the parchment page than from an array of objects taken to be illustrative of his times.

The exhibition only hints at the controversy surrounding Becket’s activities as archbishop, his flight into exile, his efforts to influence events in England from abroad and his return to Canterbury at the start of December 1170. But the moment of his death is another matter. Graphic representations of the four armed knights who struck Becket down, sliced off the top of his head and repeatedly stabbed him with their swords recur across artefacts of various kinds. Many were produced soon after the event, including the spectacular stone font, carved c.1191, that has travelled to the BM from Lyngsjö in Sweden. Four ‘Becket leaves’ are all that survive of a mid-13th-century illustrated verse Life of Becket, produced at St Albans and written in Anglo-Norman French. They are superb examples of English Gothic book art, depicting key moments of narrative drama with attention to historical detail and political spin. The Lyngsjö font and the Becket leaves were produced well after Henry II had been reconciled with the Church: in 1174 he had made a barefoot pilgrimage to Becket’s tomb and been whipped before it by the monks. Yet both works firmly fix the blame on the king.

Representations of Becket’s death as martyrdom, however, illustrate a consensus that arose a while after the fact. His murder resulted in a real sense of crisis, locally in Canterbury, throughout the Church in England and also abroad. According to Caesarius of Heisterbach, Parisian scholars were divided: ‘Some said he was a damnable traitor to his kingdom, others that as a defender of the Church he was a martyr’ – positions which T.S. Eliot echoed in Murder in the Cathedral (1935). Becket’s death was shocking, but his canonisation as a saint in 1173 was far from a foregone conclusion. The French pressed for it, but it was bitterly opposed by those English bishops who recognised it as a political manoeuvre on the part of Alexander III. The objects on display at the BM capture nothing of this. Instead, they emphasise Becket’s exceptional popularity, as evidenced by the pilgrims who flocked to his shrine in Canterbury and the rapid diffusion of his cult from Scandinavia to Sicily. And they demonstrate, too, the extent to which the present glories of Canterbury Cathedral are indebted to his gory fate.

There was no established route to canonisation in the 1170s and none would emerge for another half-century (indeed, Alexander III’s formal pronouncement of Becket’s sainthood was instrumental to its development). ‘Canonisation’ simply meant papal approval of someone who was already venerated. Proof of sanctity was required, and although Becket’s biographers made a retrospective effort to demonstrate his piety in life, the real evidence started to come within a week of his death. Much to the consternation of the clergy, Becket began rapidly to acquire a post-mortem celebrity. Townspeople who were in the cathedral at the time of his death instinctively dipped their handkerchiefs or fingers in the congealing blood. Taken home and diluted with water, it became a drink with powerful effects. The paralysed walked, the blind saw, stillborn children were revived. In effect, the laity invented a form of eucharist for themselves.

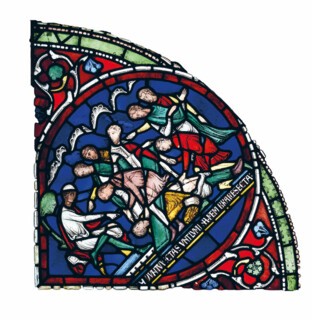

It took the monks of Canterbury some time to accept that they were now in receipt of a miracle-working martyr. Beyond Canterbury, many remained unconvinced, while to Becket’s detractors, these extraordinary occurrences were the work of demons. The controversy of his life and the manner of his death reveal with unusual clarity just what it took to establish a saint’s cult. Over time, as the monks smoothed away their hesitations, as doubters and opponents were won over, and especially after Henry II’s penance, the new consensus emerged. The cathedral exploited this by selling small phials of ‘St Thomas’s Water’, and the BM exhibition charts the discovery of these lead ampullae and other pilgrim badges throughout Europe. But Canterbury itself holds pride of place. The fire that ripped through the chancel at the east end of the cathedral in 1174 created an opportunity to build a new tomb-shrine for Becket’s remains. Consecrated in 1220, the corona (‘Becket’s crown’) became its spectacular setting: a sequence of sixteen stained-glass windows, each over six metres tall. They depict Becket’s life, death and glorious afterlife. His huge gold shrine, studded with jewels and surrounded by candles, would have shimmered in the windows’ multicoloured light. Combined with monastic chant and the heady aroma of incense, a pilgrimage to Becket’s shrine must have been quite an experience.

The nearest visitors to the British Museum can get to this is a digital mock-up of the shrine displayed on a small screen. They can, however, get right up close to one of the Miracle windows, on loan for the exhibition, in a way that would be impossible in the cathedral itself. Displayed in four segments so that the panels can be studied in detail, it is simply stunning. The representations of Becket’s earliest miracles introduce us to life in 12th-century England – and to what a saint’s mercy meant. Ralph the Leper drank St Thomas’s Water and washed his sores in it until his pustules disappeared. Two congenitally crippled sisters arrived on crutches but left walking unaided. In distant Bedfordshire, the peasant Eilward – wrongly accused of thieving – is blinded and castrated in front of a royal justice. Subsequent panels show Becket visiting Eilward in a vision, the restoration of his eyes and genitals, the amazement of his fellows at this sight and his pilgrimage to Canterbury, where he gave an account to the monks and other pilgrims. After his death, it’s made clear, Becket made dramatic interventions into the lives of struggling men and women, becoming England’s unofficial patron saint.

It was Becket’s good fortune to have grown up in a society on the cusp of documentary government; he was equally fortunate to die a few decades before new forms of piety swept through Europe, fostered by the orders of wandering preachers founded by Francis of Assisi and Dominic of Osma. It is testimony to the power of his deeply traditional cult that it thrived despite the challenge presented by a plethora of charismatic preachers, ascetics, mystics and visionaries. This is confirmed in a section towards the end of the exhibition that shows the ferocity with which, 350 years later, Henry VIII tried to extirpate Becket’s cult in the early years of the English Reformation. He had the shrine at Canterbury demolished so completely that nothing of it survives for certain (though a piece of carved pink marble probably comes from it). An array of defaced books and images are evidence of the way Becket’s cult was singled out above all others for wrathful destruction, a reflection of his symbolic power as an opponent of royal interference in ecclesiastical matters, as well as his status as a rallying point for the Catholic cause. A small piece of Becket’s skull is all that survives in the cathedral of the man himself – and this only because it was smuggled abroad by a Catholic couple in the 1590s. The cranial relic and mutilated books prove the inadequacy of legislation in eradicating firmly held religious beliefs and practices. Only physical destruction of the architecture, texts and material objects central to religious activities is approximate to this, and even so, the exhibition marks the limits of Henry VIII’s success.

Canterbury remains a major centre of Anglican, Catholic and secular pilgrimage, of which ‘Becket2020’ is the latest manifestation. This makes the exhibition and accompanying book implicit commentaries on some of the assumptions of 21st-century British culture. Both are pitched at visitors and readers who are presumed to know what an archbishop is and does and, roughly, what the psalms and Mass are. By allowing the objects on display to speak for themselves with minimal interpretive assistance (there is more in the catalogue), the curators have taken for granted some understanding of the centrality of saints and their relics to medieval Christianity and have drastically over-simplified the issues at stake in the Reformation. My fellow visitors seemed extremely well-informed, but I left this remarkable (and remarkably beautiful) representation of historical, political and religious complexity wondering what meaning, if any, the exhibition would have had to the ordinary Londoners with whom Becket once rubbed shoulders in the streets.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.