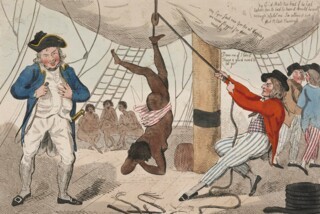

In the print that Isaac Cruikshank called Abolition of the Atlantic Slave Trade, an African girl is shown swinging several feet above the deck of a slave ship, the Recovery, a rope cinched tightly around her right ankle. She is defenceless and exposed. Captain John Kimber seems to be taking pleasure in her pain. He is corpulent, grotesque. We do not know the girl’s name. Nor did the crew who watched or assisted in her torture. They called one of her fellow captives Venus, which of course had no meaning in the village from which she had been taken, but said plenty about their expectations, intentions and transgressions.

Cruikshank based his drawing on a story told by William Wilberforce in a speech delivered in the House of Commons a week earlier, in April 1792, at the apogee of the campaign to ban the British slave trade. But while many in the country had spoken in favour of abolition – the Commons had received 519 petitions with 390,000 signatures in favour of abolishing the trade – Parliament had not. Wilberforce intended his vivid description of the girl’s anguish – she was left to die – to shock the Commons into action. There was shock. MPs demanded justice. The High Court of Admiralty took the highly unusual step of charging Kimber with the murder of a slave on the high seas. But making an example of a single slave ship captain had not really been the point for the abolitionists. Wilberforce and his allies wanted a majority in favour of the motion he had introduced in the speech: ‘the trade carried on by British subjects, for the purpose of obtaining slaves on the Coast of Africa, ought to be abolished.’

In this, they failed. Nothing happened. The Admiralty exonerated Kimber. The British slave trade thrived, reaching a new peak in the next decade, when nearly fifty thousand African captives were shipped to the Americas each year. Many in Parliament professed to loathe the trade: the abolitionists had succeeded to that extent. Loathing it and abolishing it were two very different things. A majority in the Commons responded to Wilberforce’s motion by voting for an amendment suggested by Henry Dundas, MP for Edinburgh and secretary of state for the Home Office, which backed abolition – but ‘gradual abolition’, in four years’ time, or seven, when the time was right. And even that more moderate resolution went too far for the House of Lords, which rejected the principle of abolition on any timetable, at least until the Lords had conducted its own investigation, which was repeatedly postponed during the French and then the Haitian revolutions. In the meantime, the government, led by William Pitt and Dundas, spent the next five years trying and failing to suppress the slave revolt in the French colony of Saint-Domingue in the hope of capturing its land and wealth for the British Empire. And so a governing elite that, on balance, regarded the Atlantic slave trade as appalling also felt, on balance, that stopping the trade would be even worse and extending the empire of slavery even better.

This inclination to concede the principle but postpone its application, perhaps indefinitely, prevailed within the British government until 1833, though it has received little attention in accounts of the British anti-slavery movement. Instead, historians have usually dwelled on the abolitionists’ resolve. This was the theme the leaders of the movement emphasised when they came to write their own histories in later life. And, in time, their story of triumph became the nation’s too. Few in Britain mourned the world that was lost after the slave trade was ended in 1807 and slavery in the empire in 1834. The country’s collective economic and political investment in slavery receded from public memory, as did the role played by its many defenders and the substantial record of government evasion, moderation, hesitance and deflection.

Recent events, most obviously the murder of George Floyd, suggest the pressing need for a confrontation with the deep history of institutional failure to act in the wake of spectacular racial violence. This negative impulse has a long lineage, as do its characteristic patterns of response: eventual acknowledgment, but only after a long delay; a call for action, but later, not now, at some point when the timing is better; reform, but in a way that advertises good intentions while protecting established interests; hope that the most recent scandal will not be repeated, so that the exclamation ‘this is not us’ may actually possess some truth.

Fourteen years on from the bicentenary of the abolition of the slave trade, the legacies of that moment of commemoration in 2007 have become clear. Engagement with the history of British slavery and the British slave trade has grown with the proliferation of museum exhibitions, the expansion of public history programmes, and revisions and additions to curriculums, particularly at university level. What people make of this history and what they do with it can’t always be predicted, as last year’s toppling of Edward Colston’s statue in Bristol showed. But, by any measure, the degree of attention recently given to topics once seen as peripheral to British history is impressive. According to the Royal Historical Society’s Bibliography of British and Irish History, since 2007 more has been published on the history of the British slave trade, slavery, abolition and emancipation than appeared in the entire preceding century.

No work in this field matters more than the Legacies of British Slave-Ownership project. Conceived and executed by Catherine Hall and her colleagues at UCL, it has made plain the full extent of British investment in human bondage. Many people now know that the end of slavery in the British Empire, legislated for in 1833, took the form of a negotiated settlement between the government and slaveowners, with £20 million paid out in compensation. The Legacies project used the records generated by that payout to construct an online biographical dictionary of the forty thousand people who filed for compensation. In Capitalism and Slavery (1944), Eric Williams argued that profits from the British plantations financed the industrial revolution, an argument that caused controversy among British economic historians for more than fifty years. The Legacies project suggests that in key respects Williams did not go far enough. If the precise impact of plantation profits on industrialisation remains disputed, the massive British stake in the ownership of African men, women and children in the British West Indies during the first decades of the 19th century does not.

This new financial history of emancipation has consequences for the way the political history of British slavery should now be written. It has been convenient to cast the defenders of slavery as a powerful but narrowly constituted interest of absentee planters and their colonial allies. The new evidence about who actually owned slaves makes apparent what might have been obvious all along: investment in human property ranged widely across Britain and extended up and down the social ladder. ‘The West India interest was not just a handful of planters and merchants,’ Michael Taylor writes in the final paragraph of his excellent new book, The Interest, but involved ‘hundreds of MPs, peers, civil servants, businessmen, financiers, landowners, clergymen, intellectuals, journalists, publishers, sailors, soldiers and judges, and all of them went to extreme lengths to preserve and protect colonial slavery.’ The scale of what the abolitionists were up against is only now becoming clear. To paraphrase Virginia Woolf, opposition to anti-slavery may turn out to be more interesting than anti-slavery itself.

The voyage of the Recovery provides Nicholas Rogers with his subject in Murder on the Middle Passage. The torture and murder of the unnamed girl off the coast of New Calabar has never received more than passing mention in histories of the anti-slavery movement, probably because it was a scandal without consequence rather than a turning point. Rogers has special expertise in the politics of 18th-century England, its maritime life and the history of Bristol (Kimber and the Recovery’s home port). Liverpool may now be more strongly associated with the slave trade, but in the first half of the 18th century Bristol mattered far more. Its merchants helped liberate the English trade from the monopoly of the London-based Royal Africa Company, so that any merchant with sufficient capital in any British port could engage in it. Edward Colston exemplifies this transition: he worked first under the auspices of the chartered monopoly before emerging in the 1710s as a founding father of Bristol’s slave trade. At the height of its success in the 1730s the port launched more than thirty slave ships a year. By 1791, when Kimber set sail on the Recovery, the epicentre of the trade had shifted to Liverpool, and Bristol’s merchants had come to concentrate on the shuttle traffic with the West Indian colonies, carrying sugar and other commodities. But this had little effect on the prevalence of pro-slavery opinion in the city. When in 1787 the abolitionist campaigner Thomas Clarkson visited the Bristol docks to ask men who had served on slave ships for information, the city fathers directed their employees and dependants to keep quiet.

Most sailors on the slave ships had no stake in the trade. They received wages rather than shares. Only officers could expect to profit from a successful voyage. The rest of the crew hoped to survive the venture, to avoid getting into trouble with their superiors, and to find rewards and pleasures where they could. So, although they had seen much, most would say little. A few sailors told Clarkson that they hated the traffic. No one, however, thought that much could be done about it given the economic interests at stake. Some of them pressed rather more urgently for the abolitionists to help relieve the sufferings they experienced while working on the ships. Clarkson reported that nearly half the sailors who left England on slave ships never returned. He exaggerated a bit, though probably not intentionally (when he was doing his calculations he lumped together those who stayed in the Americas after the journey with those who died along the way). Nonetheless, mortality rates among sailors were brutal. Roughly a fifth died from malaria, yellow fever or other diseases while collecting captives on the West African coast and guarding them during the Middle Passage. The sympathy Clarkson expressed for these men’s experiences helped him gain access to the information the abolitionists eventually brought to Parliament. A few crew members became whistleblowers, and this was how the story of the murder on the Recovery came to light.

The abolitionists wanted Kimber’s crime to be recognised as typical. The danger was that it would instead be perceived as so extraordinary that it could not possibly be true. It can be difficult to make the spectacular seem representative: atrocities often acquire their emotional power from a specificity that belies their frequency. The abolitionists needed Kimber to serve as an example rather than become the point. We’ve seen in our own time how quickly attention comes to centre on ‘bad actors’ rather than on the institutions and norms that create or enable them. Rogers shows the apologists for the slave trade perfecting the arts of deflection: the so-called scandal is not as scandalous as it seems; the incident has been taken out of context or blown out of proportion by ill-informed ideologues; those who know the truth of how things work also know best how they might be improved; if a scandal did occur, responsibility lies with the person or persons who deviated from the norm rather than with the norm itself, which could perhaps bear reform but does not require dramatic change.

Bristol’s leading citizens came to Kimber’s defence: the mayor, its MPs, the Society of Merchant Venturers. This is telling, because they could have sacrificed him for the good of the trade, acknowledging his depravity so as to indicate their own capacity for self-regulation. Instead, they closed ranks. They understood that the reputation of the British slave trade was at stake, that it would be difficult to separate the charges against Kimber from the larger allegations the abolitionists had made against the traffic. So instead they destroyed the reputation of the accusers. Kimber’s counsel told the court that the ship surgeon, Thomas Dowling, and the third mate, Stephen Devereaux, held grudges against Kimber, and that overeager abolitionists had exploited these unmerited grievances. Dowling and Devereaux stood no chance against these influential men. Eight months after the High Court of Admiralty acquitted Kimber in 1792, the two men faced prosecution for perjury. Witness intimidation, character assassination, manipulation of the judicial system: this was the way British slave traders and their allies dealt with threats from within their ranks.

The British plantation lobby rarely receives credit for the skill with which it defended colonial slavery. Taylor’s book is one of the few studies to give it equal time. For nearly half a century, slaveowners blocked emancipation schemes, neutered reform proposals and terrorised those in the colonies who threatened the established order. It helped that they had the right friends. Tory governments spent the 1810s and 1820s appeasing plantation owners and slow-rolling abolitionists. George Canning, foreign secretary from 1822 to 1827 and briefly prime minister, fobbed off opponents of slavery by pretending to agree with them. He declared that personally he ‘abjure[d] the principle of slavery’. He brought resolutions to the Commons that called for the mitigation, amelioration and gradual abolition of slavery. But these were mostly for show. Canning made little effort to implement the measures he endorsed. He allowed those with West Indian interests to determine for themselves what constituted suitable reforms. He let lobbyists write the terms of the regulations that would govern them. This meant that the slaveowners would decide when the time for emancipation had arrived, when it was ‘compatible with the safety of the colonies, and with a fair and equitable consideration of the interests of private property’, as he put it. Since the criteria of ‘safety’ and ‘equity’ were deliberately vague, and since few expected agreement on what those conditions would look like in practice or on how they might be achieved, it wasn’t clear whether emancipation would ever come. In 1824 the abolitionist Thomas Fowell Buxton ruefully predicted that it might take seventy years.

British West Indians did not rest easy, though, even with this protection from the men Taylor calls their ‘Tory guardians’. There was more at stake for them than their property in persons. They worried about the stability of the colonial social order, their right to self-governance, their standing with a national government that had approved and encouraged decades of investment in West Indian lands and captive African labour. They had a way of life to defend. Taylor describes the secessionist impulse that coursed through plantation society in the 1820s, a subject most accounts of British emancipation have minimised because the possibility of an American revolution in the British Caribbean seemed so unlikely at the time. A war of attrition of the sort that delivered independence for the thirteen colonies would be impossible in a situation where the slave population outnumbered the settlers by between eight and twelve to one. Historically, the British in the West Indies relied on the army and the Royal Navy to protect them from their own slaves in times of war, particularly during the American and Haitian revolutions. If they could not pursue independence, some of the West Indian elite thought they should try to find other guardians, perhaps the United States, where in the 1820s opposition to slavery was less ardent, less organised and less likely to influence the national government.

The West India interest was both powerful and insecure. Fear of slave revolts generated existential dread in the British Caribbean. Talk in Britain of emancipation gave rise to doubts about where metropolitan sympathies would lie. In the last days of 1831 thousands of enslaved Jamaicans put plantations to the torch. The insurgents believed that the British government had enacted emancipation and that colonial officials were refusing to implement it. Something like civil war ensued, with British colonists and Anglican clergy pitted against sixty thousand enslaved rebels and some free black Dissenting missionaries. Observers in Britain feared that Jamaica might be the next Haiti. It took a brutal counterinsurgency led by Sir Willoughby Cotton – ‘a veteran of Wellington’s campaigns in Spain and Belgium’, as Taylor describes him – to defeat the uprising. An orgy of executions followed and for a year, Church of England vigilantes roamed the island terrorising the Baptist clergy whom they blamed for inciting the revolt.

Historians now see the Jamaican uprising as precipitating a chain of events that culminated in emancipation in 1834. Under different historical circumstances, Taylor suggests, the consequences might have been different. Eight years earlier there had been a similar slave uprising in the British South American colony of Demerara. That rebellion had ended the same way as the 1831 Jamaica revolt in one respect: British soldiers slaughtered the insurgents and colonial officials tortured and killed its leaders. But rather than precipitating emancipation, the Demerara insurrection stigmatised anti-slavery. In 1823, Taylor writes, ‘the abolitionists were decried as traitors to the empire and condemned as if they had led the rebellion themselves.’ The West Indians had abundant experience in using slave rebellions as justification for pro- slavery politics.

This time, however, the bloodshed in Jamaica seemed repulsive to polite society in Britain and, even more important, alienated the new House of Commons elected after the passage of the Reform Act in 1832. That legislation pierced the political bastions that had long sheltered West Indian slavery from abolitionist broadsides as well as the weight of public opinion. Suddenly, the West Indian interest lost its friends. The Reform Act had eliminated pocket boroughs, which had secured a disproportionate number of parliamentary seats for the pro-slavers. It had also added new constituencies in the industrial North where abolitionist fervour ran high. One can see why Whig historians came to see emancipation as a Whig victory. In his final chapters, Taylor doesn’t quite avoid the triumphalism usual in histories of emancipation, and he doesn’t explore, even briefly, the political afterlife of the planter class post emancipation. This is a subject that still needs examination.

Neither Taylor nor Rogers has much to say about black actors. This is not a surprise given their subjects: ‘The Trade’, as Rogers calls the British traffickers and their allies; ‘The Interest’, as Taylor describes the planters and their apologists. Nor is it necessarily a problem. The British owners of slave ships and plantations, as well as the people who profited from the system and perpetuated it, also need their stories to be told. But the new focus on the perpetrators casts enslaved Africans either as victims of British brutality or as occasional rebels against exploitation, rarely as rounded human beings. This troubles both writers. Taylor acknowledges the difficulty: his book is purposefully and explicitly ‘a history of how white Britons have thought, written and acted about slavery’. Rogers attempts to correct for it, but in an unconvincing way.

‘There is not one extant autobiographical narrative of a female captive who survived the Middle Passage,’ the African American literary critic Saidiya Hartman wrote in ‘Venus in Two Acts’, an influential essay published in 2008. Hartman opens with the death of a different captive – ‘Venus’ – on the Recovery. She contemplates ‘the irreparable violence of the Atlantic slave trade’, how difficult it is to say anything definitive about women and men whose lives appear in the archives in the most limited ways, if they appear at all. What has been lost, Hartman argues, can never be retrieved but can serve instead as a prompt for reflection on the unknown and the unknowable. In his final chapter, Rogers dismissively attributes this line of interpretation to a ‘racial polarisation … fuelled by American identity politics’. He asks that Hartman, and others who focus on the trauma of the Atlantic slave trade and the limits of its archive, look in the record for evidence of slaves’ ‘agency’, so that they can be understood as more than ‘catatonic’ victims. We should aim to tell the story of how slaves fought back rather than how they died, Rogers argues, though he makes little attempt to do this himself.

Here Rogers betrays a limited understanding of the way the scholarship of Atlantic slavery has evolved. Not only African American scholars have an interest in the lost records of these shortened lives. Ian Baucom published a study on a similar theme sixteen years ago, Spectres of the Atlantic: Finance Capital, Slavery and the Philosophy of History. His subject was the voyage of the slave ship Zong in 1781, when the captain threw more than 130 captives overboard to justify an insurance claim. Hartman and Baucom, like the scholars who have followed them, begin their work at the point where the archives fall silent. They talk about the vast majority of people who did not and could not ‘fight back’ while emaciated, dehydrated, sick, traumatised, bereft and chained to the hold. It should not be necessary now to assert that African captives on slave ships, or anywhere else, hated their captivity and resisted it whenever they could. The historian Walter Johnson made this point in ‘On Agency’, an essay published in the Journal of Social History nearly twenty years ago. Why should we value those who died fighting more than those who could do no more than stay alive, or who failed to do that? The lonely, painful death of the tortured girl on the Recovery whose name we do not know, and the deaths of so many others, is no failing of theirs. To confront the vast and unmerited sufferings of those who succumbed and those who survived is to recognise the unfettered agency of the perpetrators. Taylor puts it well: ‘It is worth remembering that just as slavery was always something done to people, it was also something done by people.’

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.