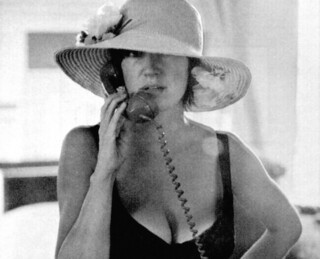

When Eve Babitz was growing up in Los Angeles in the 1950s, ‘the only thing in the county art museum that was the least bit alluring to me and my sister was the Egyptian mummy, half unwrapped so you could see its poor ancient teeth. As children, we both decided this would be the way to go, petrified and put in a museum, immortal.’ Babitz thought she’d die at thirty; she’s now 78 and witnessing her own resurrection. Youth was not wasted on her, and she crammed her life into her sentences, publishing her first memoir, Eve’s Hollywood, in her early thirties. She told her biographer, Lili Anolik, that ‘everything I wrote’ after that was ‘memoir or essay or whatever you want to call it’. ‘Death, to me,’ she wrote, ‘has always been the last word in people having fun without you.’

When she graduated from Hollywood High in 1961, Babitz wrote to Joseph Heller: ‘Dear Joseph Heller, I am a stacked 18-year-old blonde on Sunset Boulevard. I am also a writer. Eve Babitz.’ That year her family travelled to Europe so that her father, Sol, a contract violinist for Twentieth Century Fox (he delivered the stabs and screeches in Psycho), could pursue some musicological research. Babitz wrote a Daisy Miller-inspired novel, which Heller sent to his publisher: it was turned down. Deciding to be a groupie instead, she raced through the LA art and music scenes. ‘In every young man’s life there is an Eve Babitz,’ Earl McGrath, later the president of Rolling Stones Records, said. ‘It’s usually Eve Babitz.’ Ed Ruscha disagreed:

Even if she acted like a groupie, though, she never was. Groupies are passive, bounce off whoever they’re around. And she was so much of a personality – bright, a multitude of talents, and confrontational. God, confrontational! Her opinions were immutable. It wasn’t ‘I think it is.’ It was ‘It is.’

Groupiedom was a status that, like her appearance, allowed Babitz to slip in as ‘spy in the land of the privileged’.

She tried being a muse, agreeing to be photographed playing chess naked with a clothed Marcel Duchamp (‘I can’t blush,’ she said of herself). The photograph would be ‘an immortaliser’, she thought – it was also revenge on a gallerist boyfriend who hadn’t invited her to the opening of his Duchamp retrospective because his wife would be there. Duchamp, who had given up art forty years earlier to spend more time on his game, beat Babitz’s fool’s mate three times. Never a straightforward exhibitionist, she chose for the final image a photograph in which her hair covers her face.

She tried being a secretary, after moving to New York, which she hated. She was working at an alternative newspaper, the East Village Other, when the publisher accused her of embezzlement. ‘I didn’t know how much I was supposed to be paid, so I took as much as I thought I deserved. I guess it was too much.’ She introduced Salvador Dalí and Frank Zappa: ‘Dalí took one look at Frank from across the room and rose to his feet in immediate approbation.’ In New York, she wrote, ‘there are no spaces between the words, it’s one of the charms of the place. Certain things don’t have to be thought about carefully because you’re always being pushed from behind. It’s like a tunnel where there’s no sky.’ She tried designing album covers, ‘psychedelic valentines’ for bands such as Buffalo Springfield – until Earl McGrath criticised her choice of blue paint and she gave up on art.

Just as she began to worry she’d have to get married to survive, a piece she had written about Hollywood High was accepted by Rolling Stone. It was her first publication and lost her a jealous boyfriend – she had allowed him to rearrange the paragraphs into ‘a slightly more-so opening than the one I had’ – whose own writing she found ‘marvellous and exciting, even though all it was about was growing up in the Midwest’. This seems to have been her last serious relationship. ‘I got published and knew I was home free.’ In the essays and articles that followed, she favoured lowbrow topics (on life in a 36DD bra: ‘They get horny so I’m supposed to’) and provocative opening lines: ‘It seems that the only people on TV who don’t dye their hair these days are recently released captives’; ‘Architecturally, LA is a lot like epilepsy … full of grand malls and petit ones.’ She made showing off a sort of politeness – an obligation to give the reader a good time.

But no matter how more-so her performances were, she preferred the role of romantic observer-inventor:

I never had the necessary ability to suspend my own disbelief enough to act on a stage or in front of a camera with other people’s words. Besides, even I could see that something was the matter with Hollywood … The 1950s, as everyone points out, was a peculiarly charmless time in which to be an adolescent, but no one ever felt more bliss than I, accompanying an older girlfriend to Unemployment or inventing lives for fractionally viewed, careless young men in Jaguars.

In LA, as at Hollywood High, ‘the people were what was going on.’ The aim was to remain enchanted: ‘When it got dark I left, my illusions intact.’

I Used to Be Charming consists mostly of articles Babitz wrote between 1975 and 1997 for everywhere from the New York Times to Wet: The Magazine of Gourmet Bathing. She describes shadowing Francis Ford Coppola as an extra in The Godfather Part II. ‘What’s the matter with you, anyway?’ she asks, when he borrows her Brownie camera to take her picture and instead photographs mostly sky. ‘Don’t you know a thing about cameras?’ Her attachment to her own perspective stopped her from becoming too sycophantic in interviews. She removes the genius sheen from ‘Francis’, who appears as a loveable dilettante, strolling around ‘throwing chocolate-covered almonds into everyone’s mouth’ and dreaming of starting a magazine, a ‘little radio station’, a restaurant. This, for Babitz, is a sign of his incorruptibility: ‘On Francis’s side are Righteousness and Truth, Pure Untainted Visions of Ancient Glory and Modern Goodness. On the other side are the Capitalist George Grosz Money Masturbators, amassing Power in secret vaults.’

Babitz’s profiles draw attention to her own preoccupations. The question of ‘getting it right’ recurs (‘it’ being art). In Eve’s Hollywood she describes watching a conductor who would ‘pick a few measures just ahead of where it wasn’t working and say that that was the part they had to iron out, and what usually happened is that the musicians would concentrate so hard on a part they were already doing well that the part they were doing badly followed without a hitch.’ In one of the best pieces from I Used to Be Charming, originally published in Esquire, she describes the time she picked up Jim Morrison (‘He was Bing Crosby from hell’) and tried to rename the Doors: ‘I dragged Jim to bed before they’d decided on the name and tried to dissuade him; it was so corny naming yourself after something Aldous Huxley wrote. I mean, The Doors of Perception … what an Ojai-geeky-too-LA-pottery-glazer kind of uncool idea.’ Babitz’s famous boyfriends didn’t become famous until after she knew them. ‘So it turned out that power was the quality of knowing what you liked,’ she writes. She was set in her ideas. The artists she hung out with were funnier than the comedians; Steve Martin sitting at the bar in the Troubadour ‘could never bring himself to look on the bright side of total debauchery or “overboogie” … In fact, sometimes I’d look at Steve sitting there and say to myself, “Oh, poor Steve, he just has no sense of humour.”’ It was Babitz who put Martin in the white suit that became his trademark.

Her preoccupation with getting it right didn’t make her a perfectionist. ‘I have never liked perfect things, they give me the creeps.’ She accosts a man from New York: ‘How can you look like this? You’re so neat, you’re perfect, and I’m … I’m just from LA.’ The evening unfolded and ‘he remained perfect and only I got drunk.’ Not having good taste, that is, ‘being too LA for words’, was necessary in the face of East Coast pretentiousness. ‘Jeez,’ she says as she visits a friend’s home, ‘I know Aaron knows a lot about art because the paintings in his house are too overbearing for words; they clash with your sensibilities here in LA. They’re like hearing the subway, and you don’t want to hear the subway in LA.’ Her ‘taste for slapdashedness’ and impatience bred immediate images, phrases that sum up a particular state or words chanced on rather than laboured:

In the tenth grade I took a test and got the highest grade in the city in grammar. I had learned the kind of cosy mathematical sense of wellbeing you can derive from a parsed sentence. I liked the way a sentence looked all Royal Familyed up with bloodlines and right angles, all those reasons. But it seemed to me after looking at it that a point that parses is a point that people’d rather go to the circus to avoid seeing than hang around and appreciate … I wonder if [Picasso] felt the same way when someone said, ‘you can’t draw a face like that’ when the fact that the person could tell it was a face meant you could, as I felt when an instructor said ‘“be” is never a noun.’

Eve’s Hollywood is dedicated to a long list of supporters, including tempura, her gynaecologist and ‘the Didion-Dunnes for having to be who I’m not’.

Babitz’s medium is the energy that comes from enthusiastically recommending, judging, doing something verboten. As a cure for a nervous breakdown, if you can’t afford ‘a Henry James one’, she prescribes shocking the seller at Tiffany by ordering garishly coloured notepaper.

Of course, what I ought to have gotten was ‘Ecru-White Kid’ with black engraving or, at worst, dark green or brown script … if it weren’t bad enough that my first venture into Tiffany stationery was cards of buff-peach, it turned out that the colour of the engraved script I wanted was turquoise. Her frozen downcast eyes immediately told me I was never going to get by with anything so demented as turquoise.

She ends up with ‘bloodcurdling scarlet’ lettering and feeling ‘slightly sorry for poor Henry James’ who had to go to England and start again ‘when a simple trip to Tiffany’s might have saved him the trouble’.

She had a line in cures of this sort. For a friend’s midlife crisis, she suggested the tuna melts at her favourite deli, Victor’s, where ‘the onions were grilled beyond dreams of gluttony, the tuna was fluffy, the Swiss cheese on top melted like a dream, and it was altogether a promise fulfilled’. For overdoses, like Janis Joplin’s: taquitos on Olvera Street – the sauce ‘deserves the Nobel Prize’. Not all the people who fascinated Babitz were celebrated, or celebrated in the way they should have been. Marni Nixon, a teenage mum and opera singer with a ‘crystal casual voice’, breaks Babitz’s schoolgirl heart when she hears her rehearsing. Marilyn Monroe wasn’t recognised for her art. Many of Babitz’s beautiful contemporaries didn’t make it into the movies. But even her cat Rosie had connections. Rosie’s mother, a Siamese, once belonged to Frank O’Hara, a detail that suggests lineage shouldn’t be taken too seriously either. When the cat dies, Babitz admits: ‘I couldn’t feel bad for her; she wasn’t nice.’

The dissonance produced by living in LA convinced her that the only limitation was the limit of one’s own magical thinking: ‘You can change the boundaries of heaven, just so long as you don’t really believe in it or anything that anyone tells you … It’s the frames which made some things important and some things forgotten. It’s all only frames from which the content arises.’ This determination to remain playful or die is of a piece with the narrative voice of Eve’s Hollywood. Later works, such as the relaxed, seductive Slow Days, Fast Company (1977), don’t try to stun, but here she seems to be writing at the reader, explaining, conspiring, gossiping, sharing theories, opinions, tips, assuming a benign authority. She navigates the city’s highs and lows during weekday mornings spent ‘maniacally’ roller-skating with her lover Annie Leibovitz. Her attitude switches from reverential to disinterested in a beat. She scrutinises the different powers of beauty, art, money – ‘Beauty, unlike money, seems unable to focus on the source of the power,’ beautiful people don’t like to concede ‘why they were invited’ – without becoming cynical about the mystic forces that shape LA. In Slow Days, she is more willing to cede control. Faced with the Santa Anas, she notes that ‘Raymond Chandler and Joan Didion both regard the Santa Anas as some powerful evil, and I know what they mean because I’ve seen people drop from migraines and go crazy. Every time I feel one coming I put on my dancing spirits.’ Of a disruptive acquaintance: ‘She was like the Santa Anas, and if she hadn’t kissed me, William and I would probably still be going to the museum together. Entombed.’ Of an apartment: ‘Disorder had the upper hand.’ Of a boyfriend: ‘Shawn lumped all love together and was drawn to whatever burned hottest, which is usually me.’ A lot turns on her use of ‘usually’.

The 1980s were a comedown. She and her fellow ‘shimmering charismatics’ had always been ‘such gluttons for narcissistic fantasies … that we began our lives knowing that sinking into gracious old age, being happy about grandchildren, planning family dinners, being proud we put children through college or had children not in jail – these were not the things we meant by “life” when we started. I mean, they may have happened, but not on purpose.’ Aids was killing her friends, ‘the biggest events in people’s lives [were] receiving cakes at meetings for how many years they’ve been sober’, the political gains of the 1960s were slipping away, artists were selling out, and the whole country ‘was off on this Reagan roll, dreadful Trumped-up cities, but especially LA; a city built on the premise that downtown was unnecessary suddenly had one, we were rolling in traffic, quaint old neighbourhoods fell to “improvements” and people squeezed out of Central and South American countries by war and poverty fought their way to “paradise” – us, LA.’ The Chateau Marmont had been ‘recarpeted, repainted, and the phones work almost too well’, ‘ugliness was merrily multiplying [and] people would forget about each other and settle for BMWs instead.’ Now, when she saw someone attractive, she wondered, ‘If they’re so cute why aren’t they dead?’

In 1992, the LA riots erupted. In a short story called ‘Expensive Regrets’ Babitz documents a fling she was having at the time. She assumes the burning smell in the air is something to do with passion. As reports of the riots start to seep in, she tries to integrate them. They jangle. Her boyfriend, Renzo, ‘was wearing a faded olive-green T-shirt that matched his eyes so perfectly, it made my heart melt like the melted electronics stores all over the town’. Renzo is into yoga. ‘If everyone in LA did Sun Salutations instead of drive-by shootings, the fires would have been within, instead of without.’ Is she serious?

‘I’ve always tried to cultivate a disillusioned and world-weary attitude to counteract my rude streak of optimism,’ Babitz wrote, ‘which gets in the way of reality.’ By 1997, she was working on a book about learning the tango, ‘the dance of the truly driven’, in which partners still had ‘a kind of drooping joie de vivre’. Nobody in tango class ‘ever heard of a “Bo-da” meeting, nobody ever heard of suicide hotlines, nobody ever heard of any self-help programme – wallowing in self-pity with only a touch of stylish irony was the only idea. And I loved it for its fearless wrongness.’

That was the year of her accident. Babitz refused to address her brush with death, the subject of the book’s title essay, for years. She tells it as if to an audience: ‘Here’s what you would have witnessed if you happened to be standing outside the Raymond restaurant in Pasadena on April 13, 1997.’ Lighting up a cherry-flavoured Tiparillo cigar in her car, Babitz set her skirt on fire and her tights melted into her legs. She rolled around on the grass, setting that on fire too. ‘Third-degree burns, which is what I had, meant that my nerve endings were burned off. So wasn’t in much pain at all.’ Babitz planned to rub on some aloe and go out dancing later with Paul Ruscha. Her sister insisted she go to the intensive care unit. ‘Over fifty without health insurance. Did that make me a real artist?’

A cigar? ‘It was just a fad,’ she explains to the male doctors who call her ‘Eva’. ‘A Demi Moore type of thing.’ (The previous year Demi Moore had been on the cover of Cigar Aficionado, ‘a fat cigar in her mouth’.) Babitz seems incapable of negativity, except in matters of taste. She was now ‘a blackened mermaid’, but still objected to the décor of her hospital room: ‘funereal teal blue everywhere’. Given a prognosis for survival, she was upbeat: ‘To me, fifty-fifty meant I had a good chance … At least I hadn’t burned my face or run into a traffic pole headfirst.’ The only way she knew she was getting better and the nerve endings were growing back was when she began to feel more pain. Finally, she starts to want things again – a tuna sandwich, a muscle-bound ‘extremely cute male assistant’ – and ‘the cravings made me feel human.’ She flirts. ‘I used to be charming before I got here.’ She had to relearn how to walk. Six months after moving to another hospital, she comes back to the burns unit and finds the trauma had warped her memory. ‘The whole place wasn’t that obnoxious pale turquoise … there was only a single curtain in that horrible shade. The jacuzzi, which I experienced as a kind of baroque object of torture and relief, was just an ordinary long aluminium tub … the distance between the bed and the bathroom, which I thought must be a city block of pain, was no more than ten feet.’ Bankrupt, she printed some new business cards: ‘Eve Babitz. Better red than dead.’

She stopped publishing. Seventeen years passed before Anolik published a profile of her in Vanity Fair in 2014, years during which Babitz denies she became a recluse (she claims to have been working on a fictionalised biography of her parents). Anolik found her in the LA phonebook. After the piece, Babitz’s books began to be reprinted. Reviewers now praise her for making a case for pleasure, for the present moment, appetites. She is held up, somewhat carelessly, as an example of how to be a woman and not be angry. (It’s true that Babitz hardly ever complains.) Hulu is making a dramedy based on her life. Celebrities post pictures of themselves reading Sex and Rage and LA Woman – photogenic titles but not her best work. She got into conservative talk radio around 9/11, wears a MAGA hat and reads Ann Coulter.

How would she describe the supermodel Kendall Jenner, star of Keeping up with the Kardashians, who posted a picture of Black Swans, her short story collection, on Instagram? Babitz is enthralled by beauty, which for her symbolises LA: ‘People with brains went to New York and people with faces came West.’ She had to get used to having beautiful friends, classmates who ‘had one talent – exaggerating the colour until everything else in sight looked faded’. She wrote in Black Swans that ‘children … are the ones most impaled on the sharp recognition of jealousy … Sometimes I think that jealousy, like skiing, is only for those with enough youthful stamina and energy to endure it.’ She didn’t just endure it: she turned it on its head. After all, an offence to beauty was an offence to LA, and Babitz had made herself the voice of the city. When a ‘spectacular’ girlfriend is dumped

It got colder and colder. It rained. Electricity and phones and cable TV, even regular TV and schools, went out of commission. Cars slid into ravines. People were forced to go to movies or read books by candlelight. The Auto Club Emergency Road Repair Service phone number was busy, busy, busy.

The pathetic fallacy is always narcissistic, but Babitz’s type of narcissism is extravagantly grievous. Besides, she was once giddy at her own gorgeousness too: ‘I was always scaring the timid junkies with my radiant molecules. In fact, I was obnoxiously radiant.’

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.