Fabio Barry’s book about stones alters our understanding of the sacred, or at least symbolic, nature of much of the great architecture of the past. In addition to his command of specialist modern scholarship in several languages, he has studied many old and often obscure texts, and supplies translations of these. But his ideas have developed on site as well as in libraries. In the ruins of the mountain-top Temple of Apollo at Bassae he is surprised that archaeologists have ignored the varieties of colour in the local limestones. In a monastery on Mount Athos he finds an episcopal pendant (enkolpion) supposedly cut from the marble slab on which the dead body of Christ was anointed (the ‘Stone of Unction’). He has also hunted down the few surviving scraps of ‘specular stone’ that once served as windowpanes in Pompeii and Ostia. Although he also includes discussions of synthetic substitutes for stone, such as Egyptian faience and glass and, centuries later, the development of scagliola and stucco lustro, there are four types of stone that play a major part in Painting in Stone.

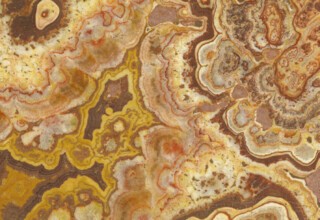

First, there are the alabasters, which are relatively soft. These are now divided into gypsum alabaster and calcite or onyx alabaster. Calcite alabaster from Egypt, commonly a creamy white with more translucent golden bands, is sometimes petalled, fleecy or cloudy in pattern, and darker types can occasionally resemble toffee. Its watery origin – often as stalactites – must have been well known and probably contributed to the old idea that mountains were able to regenerate material that was removed from them.

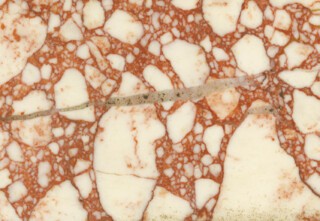

Very hard igneous rocks, notably the granites, feature less prominently, but Barry gives much attention to imperial porphyry, perhaps the most prestigious of all stones other than gemstones on account of its finely speckled purple colour, its remote mountain source in Egypt, its proverbial hardness, and its associations with blood, empire and immortality. The obsession with porphyry at the Medici court was the subject of Suzanne Butters’s The Triumph of Vulcan (1996), which includes a photograph of the English sculptor Stephen Cox (born 1946), stripped to the waist, caressing the smooth flanks of the quarry on Mons Porphyrites. Cox was the first person since antiquity to obtain porphyry from this source, and a huge chunk of it, partly worked by him and partly by Roman quarry slaves, serves as the frontispiece of Barry’s book.

Between these two extremes of soft and hard stones there are the marbles. White marble is quarried and occasionally mined at a number of sites in Greece and Italy. Describing and illustrating the different types is exceedingly difficult, but Barry includes a photograph of a fire-scorched Parian marble head of a goddess (now in the archaeological museum in Seville) because the nature of its damage helps us to appreciate ‘the corpuscles of light that seem to be sealed within Parian’s macrocrystalline grain’. Coloured marble can of course be veined, streaked, clouded, mottled, or it could be a breccia – that is, with irregular, sometimes jagged, inclusions. The Mount Athos enkolpion is of breccia corallina. The pale ‘amber matrix contains clasts both opalescent and clouded, like pearls or salty tears’; texts identify these as traces of the Virgin Mary’s sorrow.

For geologists the word ‘marble’ now applies only to metamorphic stones, but in common and traditional usage it covers numerous polishable limestones, including the mottled orange and tawny red stone of Verona that was used for the diapered pattern of the façade of the Doge’s Palace in Venice and for the paving of Venetian churches – as well as thousands of bathrooms throughout the world. The dark brown or grey-green fossiliferous marble from Purbeck in Dorset that was much used in English medieval architecture and sculpture is also a limestone. Barry notes that Master Henry of Avranches, the cosmopolitan 13th-century Latin poet and secular priest, likened Purbeck stone to the shining jasper mentioned in the Bible, and to the sheen of a fingernail (an allusion, I suppose, to onyx, the name of which derives directly from the Greek for ‘claw’ or ‘fingernail’). These may have been conventional similes, but Barry takes them seriously and he himself proposes, not quite plausibly, that Purbeck marble was ‘very likely regarded as a substitute for imperial porphyry’.

He is unimpressed by the popular idea that the citizens of ancient Rome habitually regarded the presence of such stones as gratifying reminders of the extent of their empire. Little space is given to the extraction and working of stones, and he isn’t much concerned with the locations of the quarries, to which a great deal of archaeological investigation has been devoted. He pays more attention to the original meanings of the words used to describe marble. The originality of his approach lies in the attention he has given to the language through which the intentions of artists and their patrons and the response of their publics may be divined. Sceptics may discredit the motives of the writers Barry cites – the court poets who were obliged to flatter, the clerical intellectuals who mesmerised their readers with obscurantist hyperbole, the pilgrim texts that were liable to exaggerate marvels – but he makes a powerful case against their neglect.

Here at last is an authority who considers it a ‘gross simplification’ to argue that the marble sculpture of ancient Greece and Rome was completely covered in opaque paint. Why, if this was always so, bother to extract and transport with such difficulty, and at such cost, the finest Parian marble? And why was the shining whiteness of the divine statues so much emphasised in literature? Analysing the statue of Augustus as Pontifex Maximus (the ‘Augustus of Via Labicana’ in Palazzo Massimo in Rome) Barry notes that the toga is carved out of Italian marble, but the flesh out of Parian. The latter was more expensive, especially in large pieces, so we might suppose that this measure was adopted for the sake of economy, but Barry argues that the sculpture embodies the different qualities of two Latin words: candidus for the gleaming white light emanating from a divinity, and albus for the purity of the white robes.

Barry’s own prose, while lively and engaging, is also sometimes irritating. He can adopt schoolboy slang, as when lamenting the ‘sadly piffling’ remains of the ivory employed in ancient Greek chryselephantine cult statues. Occasionally he assumes redundant priestly robes: ‘The perduration of this perception reveals the enduring propriety of an extraterrestrial image.’ This line, which occurs in the chapter ‘Walking on Water’, alludes to the often repeated idea that the flagstones of Hagia Sophia, made of local Proconnesian marble (white with rippling bands of grey), resembled a frozen sea. He translates some of the Byzantine texts relating to the stones before going on to mention the admiration of Mehmet the Conqueror and several Ottoman poets, and the comparison with watered silk made by a Florentine visitor shortly before the paving was ‘submerged under Muslim prayer mats’. He then produces examples of watery metaphors used elsewhere, citing for example a German visitor to a crusader palace in Beirut in 1211 who felt, or claimed to feel, that he was wading in, rather than walking on, its marble floors. From there Barry moves on to ‘premodern’ theories of the way marble was created and cites the summary of a treatise on this subject by Avicenna that was appended to, and became confused with, the work of Aristotle.

In the last chapter before the epilogue, Barry illustrates the great marble table, its top inlaid with hardstones, marbles and alabaster mostly recycled from Roman remains, completed in 1573 for Cardinal Alessandro Farnese, later acquired by the Duke of Hamilton, and now in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, observing that it ‘heralded an industry’ in palatial furniture that was still flourishing in the 19th century. By 1820 this industry was focused on luxury souvenirs in the form of round tabletops in which a hundred or so samples of coloured stones were geometrically displayed in a matrix of white Carrara or black Belgian marble. Educational as well as ornamental, they were accompanied by keys identifying the samples for the benefit of students of Pliny the Elder and of use to anyone with an interest in mineralogy, geology or geography. By this time, as Barry notes, the ‘idea that stones held magical properties and consonances with the astral realm’ had fallen from favour and the ‘taming of the marble medium was in lockstep with the advent of geology and geochemistry as analytical sciences’.

Faustino Corsi (1771-1846), a Roman lawyer, was the great expert who supplied the scarpellini (marble workers) with the keys for these ‘specimen tables’. His publications described, classified and named the coloured stones of ancient Rome and modern Italy and also further afield (he includes the rare Derbyshire red stone drawn to his attention by the sixth duke of Devonshire). By 1827 he had assembled a thousand samples. Stephen Jarrett, a ‘gentleman commoner’ with a fortune derived from Jamaican plantations, purchased the collection for Oxford University and the stones were admirably displayed in the Radcliffe Camera, together with plaster casts of the Laocoön group, the Apollo Belvedere and the Discobolus.

After the building of the Oxford University Museum of Natural History was completed in 1860, the collection was transferred there. It fell into neglect, and it is said that some of the samples had to be tactfully retrieved from service as paperweights and doorstops, chiefly thanks to the work of a young volunteer, Mary Porter, author of What Rome Was Built With (1907). Porter, whose formal education had been truncated by paternal edict, eventually studied crystallography in Germany. She returned to Oxford with a fellowship in the 1930s and helped revise the redisplay in the 1960s. Visitors in that decade included Count Raniero Gnoli, a professor of Indology at the University of Rome (and grandson of one of the archaeologists who had inspired the teenage Porter), whose Marmora Romana of 1971 – now in its third edition – employs full-size photographs of Corsi’s samples for the majority of its colour illustrations. More than any other publication, Gnoli’s book rekindled a fascination with the subject of the stones employed by the Romans on the part of both archaeologists and scholars of Renaissance art. Corsi’s collection is no longer on public display, although the museum has devised a superb website based on its contents, made possible by the Esmée Fairbairn Foundation.

There is another reason why the student of marbles should visit the Natural History Museum in Oxford, which Barry mentions in his epilogue. The column shafts of its aisles on two floors are made of coloured stones from all over Britain that are identified by inscriptions on their plinths. The quarries that yielded these shafts were partly the by-product of industrialisation: most obviously, steam power made the cutting, turning, polishing and transporting of granite economically viable in Aberdeenshire, Cumberland and Cornwall. But there were also unprecedented numbers of amateurs, described by Tennyson in 1847 as ‘Hammering and clinking, chattering stony names/Of shale and hornblende, rag and trap and tuff’. What had been regarded as ‘heaven-sent images’ in stones were now recognised as fossils. But, if the geologists dismissed the religious attitudes that Barry has reconstructed, these relics of marine life generated their own poetic and indeed eschatological response: ‘O earth, what changes hast thou seen!/There where the long street roars, hath been/The stillness of the central sea.’

Polychrome stone architecture was especially favoured in the second half of the 19th century by the high church sponsors of the Gothic Revival, who thought the fabric of the church should itself constitute an offering of the riches of nature – reminders of its divine architect. The return to a medieval style entailed a revival of medieval symbolism but not of premodern geology. The only popular stone that had a longer history of use was English gypsum alabaster, which (unfortunately) resembles streaky bacon or gelatinous beef stock. Most of the stones were newly available: Derbyshire fossil marble, together with the sickly green marble of Connemara, are combined in numerous church chancels with polished granite, likened by detractors of Victorian architecture to potted meat.

The leading supplier to church architects was William Brindley (1832-1919), a stone-carver and partner from 1868 in the firm of Farmer and Brindley. After Farmer’s death in 1879, Brindley grew increasingly interested in foreign stones and eventually became one of the world’s greatest experts on marble. He was aware of the importance of Corsi’s samples and even wanted to cut slices from them for his own reference. In the last two decades of the century he pioneered the reopening of white marble quarries in Greece and discovered the location of major Roman quarries on several Greek islands. His knowledge and enterprise, together with the new appreciation of Byzantine architecture that had been heralded by Ruskin’s enthusiasm for the basilica of San Marco in Venice and much developed by Lethaby’s great study of Hagia Sophia, helped make possible the creation of the Roman Catholic Cathedral of Westminster, the masterpiece of John Francis Bentley, opened in 1903 and consecrated in 1910.

Barry recognises the significance of the cathedral, even though it is consigned to his epilogue. More than 120 coloured stones from at least two dozen countries can be found there, some of them displayed with great imagination. Bentley’s beautiful baldachin owes much to the soft yellow Verona marble (sister of the far more common mottled orange stone) chosen for the eight monolithic columns. Yellow Verona, blended with white marble and sparkling with mosaic ornament, provides a perfect foil for the still brighter gold on the altar it shelters. The arrangements on the outer walls of the chapels in the north aisle, completed more than twenty years later, are no less distinguished. In two of these chapels, spectacular monolithic columns, one of pavonazzo marble (white, with exquisite purple veins), the other of fior di persico (resembling damson mixed with cream), are given the prominence of sacred images.

In many parts of the cathedral the marble revetments are book-matched – that is, composed of slabs sliced from the same block and arranged in sets of two or four so as to present symmetrical patterns. Barry explains the way this ancient technique created images suggestive of faces of saints or the Virgin that were sometimes regarded as ‘miraculous apparitions’. The patterns are often reminiscent of the curved folds of suspended drapery but the quivering concentric ellipses and the extended vertical lips formed by the book-matched panels of cipollino verde in the Chapel of Saint Joseph in Westminster Cathedral suggest the passage through which we all descended into this world. This is unlikely to have been consciously intended, but in some cases an irregular embryonic cross appears in the centre of the patterns, which surely was carefully devised. (Cipollino verde, named for its resemblance to sliced onion, was one of the stones that Brindley extracted from rediscovered Roman quarries.)

Barry also illustrates the Chapel of St Andrew, appropriately adorned between 1910 and 1915 with Scottish granites and with marble from a small quarry on Iona, now abandoned. Iona stone is nearly white, with flecks of green like floating weeds, and since St Andrew was a fisherman it is a delight to detect, inlaid in this stone in appropriately coloured marbles, numerous marine creatures, including a baby shark, a crab, a lobster and an eel. A deeper stream of darker, grey-green Scottish marble meanders through these shallow waters, which surround book-matched slabs of dark violet and white swirling in a pattern similar to that of a sliced head of red cabbage and here evocative of churning surf. This stone is identified by Patrick Rogers in his guide to the cathedral’s stones as ‘Fantastico Viola’, a recent trade name for a variety of richly veined marble from the quarries of Carrara and Seravezza.

It may be that when marbles were thought to be liquid in origin – when ‘few doubted that rock crystal was a form of ice that had been frozen by primordial cold’ – that belief prompted the similes that Barry so admires in late antique rhetoric, but the watery paving in the Chapel of St Andrew affects us just as powerfully as the Byzantine examples that inspired it. Barry writes in his preface that ‘with the gradual erosion of the four-element theory … the poetic imaginings that fill this book were sacrificed and lost to folklore.’ But metaphor and symbolism needn’t depend on ‘premodern’ beliefs. While it’s true that modern medicine ignores the humours, ‘fiery’, ‘wet’ and ‘earthy’ are still in use as epithets for personality types. We can still see fire and embers in africano marble; it can also suggest bruised flesh. Many other stones are, as Barry has it, ‘incarnational’. More generally, stones are ‘veined’, just as meat is ‘marbled’ with fat and so on.

At the climax of one chapter Barry takes us to the cathedral of Ávila in central Spain, noting that its nave is constructed of one sort of local granite but that another granite, ‘like no other’, a stone known as piedra sangrante, with a pattern resembling spattered blood, is used for the internal walls of the chancel – ‘the site of the Eucharistic sacrifice, where bread became flesh, and where the transformation of wine was as miraculous as getting blood from a stone’. But did the clergy of Ávila believe that the granite contained traces of Christ’s blood, as was certainly the case with the various columns venerated as relics of the Flagellation that Barry lists elsewhere? We are not told whether they did, and I would suppose that for them it was a potent symbol, as was the colour of the two monoliths of imperial red granite from Kalmar in Sweden that were chosen to frame the nave from the entrance of Westminster Cathedral, which is dedicated to the Most Holy Blood.

Yet the human mind certainly has changed. Few, even among the pious, who today admire Bernini’s sculpture of St Teresa elevated on clouds believe that this miracle actually occurred or that an angel pierced her with a dart. Bernini’s original public did and Barry argues that for them the miraculous was also present in stones. One of his most remarkable passages is devoted to Bernini’s Cornaro Chapel in the church of Santa Maria della Vittoria, which is the setting for this sculpture of St Teresa. Having analysed the way coloured marbles are employed here to imitate cloth and even wood he notes that ‘on the altar wall that links the heaven-bound Teresa and descending heaven on high, they instead foreground an image of their own “geological” nature’ as this was then ‘vividly imagined’. He describes the way these stones might have been seen and felt by the believer. ‘Divine light is not only illumination, it is fecundating, it is heat … the material returns to its thermoplastic state and matter is transformed before the eyes.’

Barry believes in the superior powers of the ‘premodern’ mind, but he also has faith in the contemporary sublime. A full-page illustration of Olafur Eliasson’s The Weather Project (2003) in Tate Modern’s Turbine Hall is placed opposite a view of the interior of Hagia Sophia. A large colour illustration of Dan Flavin’s fluorescent tubes accompanies, silently and somewhat comically, an account of the radiant white of the resurrected Christ depicted by Fra Angelico. Barry concludes with an enthusiastic description of a series of high-tech images of the performance artist Marina Abramović, her grimacing face cut in alabaster, which seem to me worthy of a sci-fi horror movie. It is far more rewarding to meet Barry in the library, explaining and translating an ancient text. And among the ruins of Delphi he is an incomparable guide, observing how marvellous it must have seemed when the dawn light, filtered through the fine translucent marble tiles, crept across the floor.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.