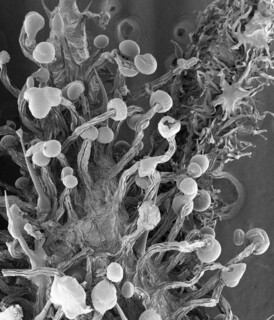

At the start of the First World War, 12-year-old Tom Harris moved with his family to a semi-derelict mansion on the outskirts of Leicester. Struggling at school and with few friends, he built a world for himself from its garden, a museum of pressed plants and tree samples. He established a fernery – complete with grotto – and spent evenings ‘skeletonising’ dead animals, which he kept in buckets on the roof. This industrious boy became a distinguished paleobotanist, whose investigations into the structure of living matter enabled him to describe lost landscapes and species. After he died, his name was given to the botanical garden at the University of Reading, the site of my earliest childhood memories. A huge Turkey Oak stretches out over the lawn like a great candelabra. Beneath it are spiralling ferns and mossy ledges, furrowed barks and conkers. This world of pattern and texture, which Harris spent his career tracing, is as natural to humans as it is to plants. We can find it by rubbing our eyes, in the phosphenes flashing against our eyelids, and in the fractal patterns of our fingerprints. We can see it more easily by using microscopes, or ingesting plants with entheogenic or mind-manifesting properties – as in the crystalline visions induced by ayahuasca. The shapes of nature, what used to be called ‘sacred geometries’, are the closest thing we have to a global aesthetics.

The Botanical Mind at Camden Arts Centre (currently closed, viewable online) brings together artworks from different centuries, continents and belief systems that consider our relationship with the plant world. Jung’s illustrations for his Red Book introduce the cosmic tree – a link between earthly and celestial realms – and the mandala. His Tree of Life combines the two in a heavily worked watercolour. At the bottom of the page, the red earth and its creatures form an intricate grid, tangled with roots. Above, the tree’s crown swirls out like flame, from a white flash in the centre to a deep blue edge. The careful shading suggests activity and immersion – the mandala as meditation device – but it also functions as a symbolic representation to be decoded or analysed.

Jung’s illustrations appear stiff in comparison to two small pictures by the American artist and fisherman Forrest Bess. Bess used a limited palette, just three or four colours per image, without any of the surface pattern associated with cosmic diagrams and none of the overt symbolism. Instead of a tree, he paints a pale stick figure reaching up from a dark world towards the rising sun. The paintings have an intense energy. Bess’s simple mandala suggests better than Jung’s ‘a psychic centre of the personality not to be associated with the ego’, its viscous paint and wobbly symmetry giving form to the effort of prolonged introspection.

Variations on the tree and mandala, the snake and the axis mundi, multiply in the tantric, Surrealist and Christian examples on show. There is the Rosicrucian symbolism of Charles Filiger, the sweetly humanoid mandrakes of the 15th-century manuscript Ortus Sanitatis, mediumistic drawings by Hilma af Klint and Emma Kunz, and woven textiles by the Shipibo-Conibo people of Amazonian Peru, the patterns (kené) of which echo the songs sung in ayahuasca-guided healing ceremonies. In the exhibition, connections are made lightly, simply by the presentation of repeated shapes and overlapping iconographies, with greater context given in the catalogue (presumably to allow the mind to create its own patterns).

For many of the works, this feeling-thinking approach reflects the way they were made. Wolfgang Paalen’s fumage pictures from the 1930s, for instance, are repeated shapes left on paper by candle smoke, an exercise, we are told, in unconscious communion. He saw painting as an opportunity for ‘affective identification’ between viewers and ‘painting-beings’, a stance that left its impact on a generation of American painters. Abstract Expressionists, especially Rothko, made mainstream the idea of the aura as both spiritual emanation and emotional interaction.

There have been limited opportunities for this kind of communion at Camden Arts Centre, which was closed for most of 2020, and the exhibition looks unlikely to reopen in 2021. Throughout its interrupted run, however, the show has existed as a website, bolstered by new commissions and supplementary reading. The sprawling nature of the project is reflected in its online presentation: you can enter in roundabout ways, veer off to read a dense essay on the theology behind Hildegard of Bingen’s botanical writing or watch the ethnobotanist Terence McKenna delivering a practical course on using psychoactive plants to achieve ‘the dissolving boundaries of the vegetable mind’.

An accompanying podcast series covers plant intelligence, the Amazon pharmacopeia and ecologist Stephen Harding’s concept of ‘Gaia alchemy’, which seeks to access the intelligence of the earth through meditation and shamanic ritual. To address the climate disaster, Harding urges, we first have to heal the split between science and rationality. One of the new commissions is a guided meditation by the artist Joachim Koester: you begin as a mantis, grow into a plant and by the end you are floating without a body at all. It is best experienced, the voiceover suggests, close to the brink of consciousness – a state that would be tricky to reach in the Camden Arts Centre.

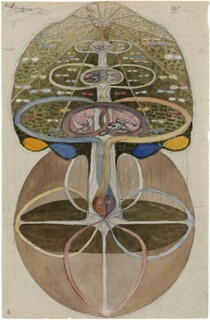

One of the central images on the website is an illustration known as Cultivating the Cosmic Tree from Hildegard’s 12th-century book of visions, Scivias. It shows a world with the tree at its centre, an embodiment of the divine ‘greening’ energy she calls ‘viriditas’, from which both soul and mind emerge. ‘Know that you are a plant,’ she counsels, ‘and know, furthermore, that your knowledge, hued with a fading green, is the afterglow of vegetal growth.’ In recent years the belief in a conscious, interconnected plant world has been taken up by writers, for whom, as the poet Rebecca Tamás argues, ‘the basis of new thoughts must be equality, not only between humans but of every being on earth.’ Hildegard’s concept of a world in which self emerges through plants provides a prototype for this. In a reversal of gender stereotypes, she figures the Virgin Mary as ‘the greenest branch’, a symbol of virility and wisdom, while Jesus is the flower. This vision shares much with Yggdrasil, the unisex cosmic tree that connects the nine worlds of Norse mythology, and to which af Klint returned repeatedly.

A series of works by Andrea Büttner looks to plants for accounts of human sexuality. Her photographic slides flick between images of moss enthusiasts pressed to the hillside, their faces close to the ground and their bums in the air. The accompanying text, influenced by Linnaeus’s description of cryptogam reproduction as ‘clandestine marriage’, relates lichens and moss to queerness, hidden sexuality, smallness and shame. It also recalls the anthropomorphising language of Maeterlinck, who couldn’t help but marvel in The Intelligence of Flowers at the ejaculation of a balsam apple: ‘As if we succeeded, relatively speaking, in emptying ourselves in one spasmodic movement and had shot all our organs, innards and blood half a kilometre from our skin and skeleton.’ Sometimes the project goes too far, as with the assertion in the podcast that ‘it is actually a fact that nature is queer.’ But it does present a wide-eyed challenge to our preconceptions. It also provides the bearings for a new story, what Donna Haraway calls the ‘big-enough story’. The oldest known plants, a clonal colony of aspens in Utah, date from more than seven thousand years ago, almost a millennium before the earliest fossils indicate the impact of humanoids on the planet. In plant time, at least, we are relatively young.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.