For years, I impatiently clicked ‘Accept Cookies’ without, I confess, really knowing what a cookie was. It turns out that it’s a short sequence of letters and numbers that a website generates and deposits in your browser. From then on, whenever you make a new request of the site, or visit the site again at some later date, the browser sends the cookie back to the site. That’s how the cookie identifies you – or your browser, at least – to the website. (Cookies do have expiration dates, but they may be years in the future.)

Then there are ‘pixels’. The type of pixel used as a tool to gather data is a tiny, transparent image, which you can’t see on your screen. When I first realised that, without knowing it, I must have downloaded pixels of this sort many times, I was spooked. What does the invisible pixel do? It turns out that in itself it does nothing. What matters is that your browser requests the pixel, which it is prompted to do by computer code that a webpage downloads to your browser when it accesses the page. As a programmer explained to me, ‘the code runs in the browser to gather as much information as it can and encodes that into the address of the image it requests.’ Whatever you look at on the site; whatever you buy; the things you add to a shopping cart but don’t buy; information about your browser: all this and more can be transmitted via this process. The most widely used pixel seems to be Facebook’s, which the advertising technology firm QueryClick reckons is present on 30 per cent of the world’s thousand most visited websites. Facebook’s machine-learning algorithms use the data the company’s pixels generate to optimise the delivery of ads. In an article in the Atlantic last year, Ian Bogost and Alexis Madrigal reported that these pixels were playing exactly that role for the Trump campaign.

A conversation with another programmer prompted me to look into ‘fingerprinting’. Fingerprinting a phone or laptop means scanning it for characteristics that will help to identify it at a later point or in a different context. What model do you have? Which language setting are you using? Which browser, and which version of it? How does your browser render fonts on your screen? Even the level of battery charge on your phone or laptop can help an automated fingerprinting system keep track of it, at least over the short term. The first advertising executive I asked about fingerprinting, last May, told me it had a dubious reputation. It is ‘clunky, not a particularly elegant solution’, and – more important – if you engage in fingerprinting ‘you’re capturing a lot of information that is unique to essentially an individual device or browser … There’s a little bit of a grey area there … Should you really be capturing all of that information?’ But not everyone seems to share his qualms. I have noticed that more and more often websites will ask me to ‘accept’ having my laptop or mobile phone scanned, for what I can only assume is fingerprinting.

Cookies, pixels and fingerprinting are just a few of the technologies in the toolkit of what Shoshana Zuboff has called ‘surveillance capitalism’.* Her starting point is the observation that digital systems of any complexity spew out massive volumes of data, much of it ‘digital exhaust’, not needed for the operations of the system or for improving those operations. Zuboff argues that Google – in her view the primary inventor of today’s surveillance capitalism – came to realise that this exhaust data, when processed by sophisticated machine-learning systems, could be used to predict users’ behaviour. What kind of advertisement is likely to interest people enough that they will click on it? And will they go on to ‘convert’, as advertisers put it – in other words, to buy the product in question?

Predictions of this kind are obviously of commercial value, and digital advertising was growing fast even before Google was founded in 1998 (Zuboff’s history is a little too Google-centric). Traditional advertising, using billboards, newspaper ads, TV commercials and the like, had always been a somewhat haphazard process that demanded from advertisers a leap of faith in its efficacy. In contrast, technologies such as cookies and pixels – again, Google was not the pioneer of these – yielded copious quantities of data, which seemed to permit both the careful targeting of digital adverts to the desired audience, and the objective measurement of the success of those adverts.

Initially, what Google sold was the opportunity to link ads to specific search terms or combinations of them: ‘cheap flights to San Francisco’, ‘erectile dysfunction’, ‘mesothelioma’. (Ads linked to that last term were notoriously expensive. You are unlikely to Google this dreadful form of cancer out of idle curiosity: there’s a high chance that you have already been diagnosed with it, so might perhaps be persuaded to join a law firm’s potentially lucrative asbestos-exposure class action suit.) Increasingly, though, it became possible to buy and sell the opportunity to show advertisements instantaneously to a particular individual (identified, for example, by a cookie) who had, a fraction of a second earlier, entered a term into a search engine, clicked on a link taking them to a website, or was looking at Facebook or another social media platform. ‘Real-time bidding’, as this came to be called, was quite different from buying and selling advertising over cocktails on Madison Avenue. Automated ‘advertising exchanges’ were set up, with algorithms bidding competitively for advertising opportunities offered by other algorithms. ‘Markets in future behaviour’, as Zuboff calls them, had come into being.

Large-scale traditional advertising is an expensive business. Automated advertising, targeted at what could be quite a limited number of likely consumers, opened up new, cheaper possibilities for startup companies such as a small clothing brand or craft brewery. As the co-founder of one startup told me, ‘you can get your product in front of a global niche audience,’ and experiment quickly and cheaply with different targeting strategies, or the wording and images on adverts. The downside is that targeting requires the collecting of data on individuals, their interests, their likely purchases and so on. An advertiser will want to know, for example, what kind of phone you’re using: someone with an Android phone is usually a less valuable target than the typically bigger-spending owner of an iPhone. And an advertiser’s algorithm will want to bid quite a bit more if it finds out, say, that someone previously had a particular product in a shopping cart but hasn’t yet bought it.

Online advertising may have been the prototype of surveillance capitalism, but in Zuboff’s view it was only the beginning. Her analysis ranges widely, from uses of harvested data that seem all too plausible – in helping decide whether a given individual should have access to life insurance or health insurance or car insurance, for example, or how much it should cost – to the downright bizarre, such as automated vacuum cleaners that try to make money on the side selling floor plans of their owners’ apartments. The techniques of surveillance capitalism combine big data, machine learning, commercially available predictions of user behaviour, markets in future behaviour, behavioural ‘nudges’, and careful structuring of ‘choice architecture’ (the actions available to users and how they are presented). Zuboff’s fear is that the ensemble is already effective in steering human actions, and may become even more so, playing an ever larger role in determining the way we think and behave.

Surveillance capitalism, Zuboff writes, doesn’t just want to know the histories of our Google searches, the contents of our abandoned shopping carts or ‘my body’s co-ordinates in time and space’. It is ‘determined to march through my self’. It is ‘imposing a totalising collectivist vision of life in the hive, with surveillance capitalists and their data priesthood in charge of oversight and control’. She doesn’t agree with the familiar remark that if a digital service is free, you’re the product. Like an elephant slaughtered for the digital ivory of its data, ‘you are not the product; you are the abandoned carcass’ (Zuboff seldom understates things). Surveillance capitalism, she believes, is increasingly stripping people of their autonomy, free will and individuality.

Zuboff is a fierce opponent of surveillance capitalism, but is she enough of a sceptic about it? Does she overstate its powers? For the past year or so I have been seeking out practitioners of online advertising who are prepared to tell me about what they do and how successful – or unsuccessful – it is, and hanging out (first in person, then online) in sector meetings in which they talk to one another. Digital advertising may be only a part of surveillance capitalism, but it remains crucial because it is still the way Big Tech makes much of its money. Google’s parent company, Alphabet, runs other businesses, but advertising currently accounts for about 80 per cent of its revenue. For Facebook, that figure is more than 98 per cent. Clustered around those giants is an ecosystem of mostly smaller firms (by no means all of them advertising agencies of the traditional kind) that sell advertising services, technologies and data.

Are the huge sums of money devoted to digital advertising well spent from the advertiser’s point of view? It’s difficult to be sure. ‘I know that half the money I spend on advertising is wasted,’ the 19th-century Philadelphia department store pioneer John Wanamaker supposedly said. ‘The trouble is, I don’t know which half.’ Today’s huge volumes of data don’t necessarily bring as much clarity as one might imagine. Everyone in the business would agree that the effects of what they call ‘upper-funnel’ advertisements are almost always small, and any effects they do have may not manifest themselves for weeks. (An upper-funnel ad, such as most of the ‘display ads’ you see on Facebook or when you visit a news website, is more like traditional advertising in that it may be shown to you even if you have done nothing to indicate an interest in making a purchase.) Online experiments to determine the effects of advertising of this kind can be like looking for a very small needle in a very large haystack, as Randall Lewis and David Reiley – two of an increasing number of economists working for tech firms – put it.

There is greater confidence in ‘search ads’: the ads you are shown when you Google something of commercial interest. You are then lower in the funnel: you may be only a couple of (easily detectable) clicks away from buying. Here, though, the problem is disentangling the causal effect of an advertisement from mere correlation. Recently I needed to replace a worn-out pair of hiking shoes made by an Italian firm, Scarpa. The shop I usually go to was shuttered, so I bought a new pair online. When I was searching for ‘Scarpa walking shoes’, I was shown ads. Did the ads cause me to buy these shoes? Even if I had been shown an ad for a particular retailer, and had gone on to buy my shoes from them, how sure could the firm be that I wouldn’t have done so had it not paid for the ad?

In what has become a famous set of experiments conducted in 2012, it was demonstrated that apparent success in advertising may not always be real. The auction site eBay used to pay Google and other search engines to display an ad even if someone’s search was actually for ‘eBay’ or included the word ‘eBay’. Such ads can seem very effective: they are often clicked on, and many are followed by ‘conversions’ (someone who searched for ‘eBay shoes’, for instance, often went on to buy a pair on the site). However, three economists working for eBay found that levels of traffic on its site were scarcely affected when it stopped these advertisements: users who weren’t shown them seemed to find their way to eBay anyway. The researchers then started experimenting more systematically by turning off all eBay’s Google search advertising in randomly chosen metropolitan areas, while continuing it in others, and concluded that the $50 million a year that the firm was spending on this advertising wasn’t making a positive return.

If you have skin in the game, if your pay or career is influenced by whether the advertising for which you are responsible is seen as effective, you may well be wary of discovering that it isn’t. Other well-known firms often do what eBay had been doing: paying to show an ad when the firm’s name is entered into a search engine. Despite the eBay experiment, that might still make sense: firms often fear that if they don’t pay for ads, a competitor could get top slot on the results page, even though Google’s rules on the use of trademarks can make it expensive, for example, to bid for the search term ‘British Airways’ if you are actually a different airline. It’s striking, though, that other big firms simply don’t seem to have tried to find out whether they too are wasting their money. Two researchers, Justin Rao and Andrey Simonov, who looked for traces of analogues of the eBay experiments in a large, detailed advertising dataset, couldn’t find them. As they put it, perhaps people who had spent money on such advertising didn’t want to take the risk that ‘past expenditure could be revealed as wasteful,’ with the cuts in budgets and personnel that might follow.

As far as I can tell, the majority of people who work in online advertising firmly believe that data collection and experimentation with digital systems do make the measurement of success possible. I think they would all agree, though, that what they call ‘attribution’ is a very difficult issue: Wanamaker’s problem in modern guise. A firm that advertises online at any scale is likely to buy search ads, standard display ads, video ads, ads in apps and so on, as well as conventional ads in other media. When a ‘conversion’ occurs, the customer who buys a product or service has probably seen a variety of the firm’s advertisements. How, then, should credit for the purchase be divided up among the various ads? Because different people often have responsibility for different types of advertisement, once again they have skin in the game. ‘Attribution is a very touchy subject in any company,’ an advertising executive told me. Marketing teams can be ‘really attached’ to a particular way of dividing up credit (for example between immediately pre-purchase search ads and earlier display ads), ‘so they don’t change the attribution model easily.’

Tim Hwang, in Subprime Attention Crisis: Advertising and the Time Bomb at the Heart of the Internet, draws a provocative parallel between the dependence of Big Tech on advertising revenues and the dodgy mortgage-backed securities that triggered the near implosion of the global financial system in the 2008 banking crisis.† Online advertising too is dogged by deception. In ‘bot fraud’, for example, the clicks on adverts are generated by computer programs, but advertisers pay for what they think is a human audience. (A lot of effort is devoted to detecting fraud, but the bots, I’m told, are getting more sophisticated. They often used to run on computers in static, identifiable locations such as poorly policed data centres, and did little more than pretend to click on ads. Now malware can install them on the phones or laptops of genuine human users. Today’s bots can fill in forms and simulate an actual person’s hesitant mouse hovers.) I’m not confident that Hwang is right in his overall argument that the effectiveness of online advertising is already low and in decline: that seems quite likely to be true of website display ads, but I’m told that well-designed search ad campaigns remain reasonably, and predictably, profitable. To the extent that Hwang is correct, though, it would suggest that surveillance capitalism’s power to shape human behaviour is weaker than Zuboff fears.

What is unequivocally the case, though, is that many advertising practitioners are under constant pressure to provide data showing that money is being well spent. There are ‘chains of persuasion’, so to speak: an advertising agency or other supplier of advertising services has to demonstrate the cost-effectiveness of those services to its client’s marketing department. That department, in turn, has to justify its budget to senior managers, and they may be answerable to owners, such as private equity firms, who take a close interest in how much money is being spent and on what. One practitioner told me that part of her job for one of her clients, a well-known hotel chain, had been to produce data-laden PowerPoint slides bearing the chain’s logo and in its preferred format, so that its marketing department could directly use them in presentations to their bosses.

Many of the divides in the world of advertising have to do with what data should be generated and how, and who should control access to it. At issue isn’t simply the targeting of advertisements, important though that is, but also ways of measuring the success of advertising and attributing the credit for it. In December, the Financial Times carried a full-page ad by Facebook – a print newspaper ad, by Facebook – denouncing Apple: ‘We’re standing up to Apple for small businesses everywhere.’ The ad wasn’t explicit about what exactly had riled Facebook, but the heart of the matter is that every iPhone or iPad has an IDFA, an Identifier for Advertisers, which identifies the device. If you are an advertiser, big or small, knowing a device’s IDFA is pretty useful: it eliminates, for one thing, any need for clunky and perhaps legally questionable fingerprinting. Previously, a user who wanted to block access to their device’s IDFA had to know that it had one (I didn’t), find the relevant setting and make the change. From now on, however, Apple is going to require every app – on pain of banishment from its App Store (a penalty that even Facebook is not prepared to pay) – to get each user’s explicit permission to access the IDFA or to track them in other ways. It’s not going to be like accepting cookies. The interface Apple is using makes it just as quick to deny permission as to give it, and Apple (which treats the App Store as its estate, and sets the rules) won’t allow apps to restrict the services they provide to those who say no. The assumption in the industry is that only a small minority of users will agree to be tracked.

Restrictions on tracking, and not being able to access iPhones’ or iPads’ IDFAs, make it harder to target advertisements to potentially big-spending app users. (Much of the revenue from game apps, I’m told, comes from a small minority of users who, having downloaded them, go on to spend hundreds or even thousands of dollars on in-game purchases.) Apple’s changes also potentially screw up ‘attribution’. If you click on an ad for a game or any other app (let’s say it’s an ad on Facebook), and the link takes you to the App Store where you install the app, Apple will, as it always has, send a message to Facebook telling it about the installation. But from now on the message will not contain the IDFA of your device. So, as John Koetsier wrote in Forbes magazine, it may not be possible for either Facebook or the app developer reliably to attribute post-installation revenue to the ad. Such ads may no longer seem cost-effective, and the bidding algorithm acting for the app developer won’t bid so much to have them shown. It sounds like a small thing, but it could trigger a substantial loss of revenue for Facebook and other companies that carry ads which seek to persuade people to install apps: that business is worth around $80 billion a year.

There are currently similar disputes, too, over the use of cookies. A long-standing principle in the design of browsers is the ‘same-origin policy’, which keeps a browser’s interactions with different websites separate, so limiting the damage that a malicious website can do. One consequence is that a cookie is readable only by the website that set it in the first place: a browser won’t send the cookie to a different website. That potentially makes the tracking of users across websites (and also attribution) extremely difficult. More or less since online advertising began, the workaround has been what’s called a third-party cookie, set not by the website being visited but by a different firm’s system. For example, the advertising technology firm DoubleClick, set up in 1996 in New York’s ‘Silicon Alley’, operated a system that generated advertisements on many different websites. When a user visited one of those websites, the system would, in the course of displaying an advert, deposit a cookie of its own in the user’s browser, and then be able to read it when the user visited another of the sites, so making it possible to connect up a user’s behaviour across the web.

There is a network effect at the heart of digital advertising. The more website publishers engaged DoubleClick to generate adverts, the more widely disseminated its cookies became, and the more information DoubleClick gained with which to target those adverts, thus becoming ever more attractive as an advertising partner. In 2007, Google bought DoubleClick, fusing its own unparalleled technical expertise (and increasing dominance in search advertising) with DoubleClick’s prominence in display advertising, owed to its exploitation of the network effect. Although automated advertising may make life easier for new entrants in other industries, network effects help make the business itself something of an oligopoly, dominated by Google and Facebook (though Apple and Amazon may be hoping to catch up).

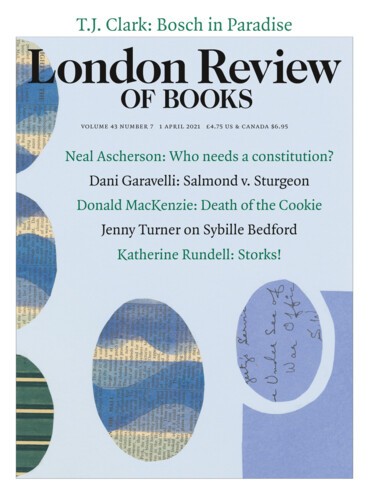

The hot topic at the online advertising industry meetings I attended last year was the imminent ‘death’ of the third-party cookie. Two mainstream browsers, Mozilla’s Firefox and Apple’s Safari, had made the blocking of such cookies part of their default configurations. (If I’m right that there has been a shift towards ‘fingerprinting’, this above all was probably the driver.) Divides on this issue run through corporations as well as between them. In January 2020, Justin Schuh, director of engineering for Google’s Chrome (which accounts for more than 60 per cent of browser use globally), said that it too intended to start blocking third-party cookies by the end of 2021. That caused consternation among Google’s advertising staff: ‘People are like, wait, what is Chrome doing there? How are we supposed to do our ads? Why didn’t they talk to us first? … Maybe some executive somewhere had seen it and agreed to this … It certainly wasn’t communicated to us.’

Decisions such as Chrome’s and Safari’s are often criticised on the grounds that they reinforce the dominant position of Big Tech by denying crucial data to their smaller competitors. Apple’s IDFA decision, for example, is being challenged legally in France by a consortium of organisations including not just advertising technology firms but also Le Monde. But I think it is a mistake always to be cynical. The engineers and programmers who work on digital advertising or in other roles for Big Tech do often have strong views, by no means always in alignment with the economic interests of their employers. One, for example, tells me that reading The Age of Surveillance Capitalism ‘made me feel bad’; on his own personal computers he uses ad-blocking software.

There is, nevertheless, something unsettling – especially in the midst of a pandemic that has forced so much of commerce and everyday life to move online – about being brought face to face with the extent to which crucial decisions that shape what can and can’t happen online are made by private companies and those who work for them. The two main tools of public policy that have been applied so far are data protection law and competition law. These leave crucial issues largely untouched, such as the way in which indiscriminate digital advertising can inadvertently fund hate speech, or the dependence of so much of serious journalism on revenue from online advertising. What’s more, these areas of law have only limited purchase on the shockingly high proportions of that revenue which can get absorbed by intermediaries’ fees and markups instead of going to publishers.

And, crucially, data protection measures and policies designed to enhance competition are often implicitly at odds. It isn’t so very painful for a big corporation to implement a data protection regime that requires it to get its users’ permission for what it does with their data, because its data transfers will often be entirely internal; such a corporation may even welcome rules that stop it sharing data with other companies. Complying with a regime of that kind is potentially much more onerous for the ecosystem of independent firms, which often need to pass data to one another. Is it possible to preserve the advantages of digital advertising for small companies while curbing invasive data gathering, and to do both while preventing the field from becoming even more of an oligopoly? Momentum has yet to build behind any clear plan for doing so.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.