In 2016, staff working on the refurbishment of the Rio Cinema in Dalston, East London, discovered a filing cabinet in the basement containing more than ten thousand photographic slides. The images were the remnants of an adult education project from the 1980s, in which a dozen or so locals – all of them young, most of them unemployed – were trained in photography and sound recording, and sent out to document life in the surrounding borough of Hackney with 35mm cameras and cassette tape recorders. They turned the material into short newsreel clips that were shown to cinema audiences before the main feature. When they started out in 1982, the group published a statement of intent: ‘We hope with the involvement of the community to bring alternative news to the general public.’

The audio is lost, but the slides have been digitised and many of them are once again available, via an exhibition at the Hackney Museum (temporarily closed) and an accompanying book.* Nearly forty years on, the most striking element in these snapshots of street life, festivals and protests are the people who lived in what was then a diverse, largely working-class neighbourhood. A family of five stick their fingers in their ears as they stand behind a crash barrier, waiting to watch the demolition of a council tower block. Two women with blue rinse hairdos are caught mid-conversation as they balance crates of Skol on a garden wall. Six teenage boys line up to show off their BMX bikes. A Traveller couple look down on a passing car as they ride a horse and trap under the A12 flyover.

The saturated colours (slicks of bright yellow, red and blue) and moments of humour or awkwardness – in one image a police constable, helmet teetering, helps push an ice cream van out of the mud at a funfair – make it tempting to draw comparisons with the English kitsch of photographers such as Martin Parr. However, the Rio group’s photographs engage with their subjects, who aren’t documented but rather are in dialogue with the camera, active participants in the cultural and political life around them. As Alan Denney (who helped to catalogue the images) notes, these pictures were part of a drive to put photojournalism, and the creation of images more generally, into the hands of people usually outside the process: ‘It was difficult to find sympathetic representations of working-class Londoners in any medium.’

The stories make the difference. A photograph of two older women sitting at a pub table behind glasses of porter and an overflowing ashtray might, in isolation, be taken as a Parr-style caricature. In fact, the women were members of the Hackney Pensioners Press, another community media project, recorded on one of the Rio newsreels while on a reporting trip to the women’s protest camp at Greenham Common. ‘When they left our untidy office in pre-gentrified Dalston and got on the bus to go home,’ a collaborator recalled, ‘these marvellous, independent-minded, articulate people were invisible … no one imagined that they had just come from a fiery discussion … thrashing out their ideas on pensions, housing, the health service, public transport, international affairs, religion, grandchildren, loneliness.’ Protests – against hospital closures, unemployment, nuclear weapons, racism and poor housing – recur in the archive. But many of these images have an air of celebration. A Welsh colliery band is shown marching down Stoke Newington High Street during the miners’ strike, their red banners and brass instruments illuminating the grey day.

A single face dominates one of the most remarkable images of protest: a passport photo of a young black man, copied in monochrome and glued onto cardboard placards. On 12 January 1983, Colin Roach was found with a gunshot wound to the head inside the entrance of Stoke Newington Police Station, which at the time had a reputation for racist harassment of the local black community. Roach’s death, which has never been explained, led to a long-running campaign for a formal inquiry and an end to police violence. No such inquiry was ever held, though the Roach family commissioned its own and published the findings in 1989.

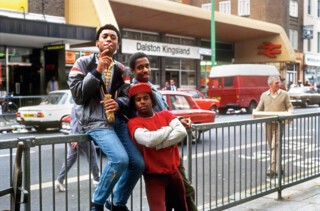

The photograph, taken on the second anniversary of Roach’s death, captures a greater sense of rage than any elsewhere in the collection. But even here, one or two protesters are caught smiling, as the others chant in unison. In another picture, three black teenage boys pose for the camera outside Dalston Kingsland Station, one of them grinning as he takes a drag on a cigarette. They might be displaying typical adolescent bravado, but they are doing so on a stretch of road that at the time was notorious for police raids – and only ten minutes’ walk from where Roach died. There is a double defiance here: the attitude of the teenagers, and the act of taking the photograph in the first place.

At less than forty years’ distance, these photographs don’t quite capture a vanished world; instead, it’s a world that is still within touching distance, close enough to make it hard to avoid comparisons. The photographs were taken between 1983 and 1988, when a seemingly unassailable Conservative government was busy dismantling much of the public sector, justifying its policies via a culture war that attacked London and other multi-ethnic cities as strongholds of the ‘loony left’. Young people in particular faced bleak economic prospects. The are obvious echoes – a Black Lives Matter vigil was held in Hackney last year in memory of Rashan Charles, who died after being chased and restrained by the police in 2017 – but it’s useful to think about what has changed. Hackney, like other parts of inner London, has been through a vicious process of gentrification, one result of which has been the colonisation of public space on behalf of the area’s wealthier residents. Many of the places recorded in these photographs are no longer available to the communities that once used them.

Members of the Rio group went on to make radio documentaries and publish newspapers, to write poetry, defend squatters and set up small businesses. One woman said the experience gave her ‘the confidence to go to university to train as a teacher’. Something of the collective spirit that these photographs express has been revived along with the archive. Over the past few years, the archivists have been posting highlights from the collection on an Instagram account, partly in the hope of identifying people and places in the largely unlabelled pictures. Followers add their own recollections in the comments. It’s this everyday intimacy, woven through with politics, that makes the photographs so appealing. Some of the best images come from two ‘day in the life’ newsreels, in which dozens of extra participants were given cameras and asked to go out and photograph the borough on a particular day. (There is a plan to recreate some of these images later this year.) One image stands out amid the glimpses of hospital canteens, tailors’ workshops and market stalls, of children playing or hiding their faces from the camera. In a back garden, a woman stands in an explosion of flowers: bright red roses, pink pansies and yellow sunflowers. Flanked by two garden gnomes, each holding a wheelbarrow filled with still more flowers, she has dressed to match her garden in a black dress with a pattern of red roses. ‘Still not been able to discover her name,’ the archivist wrote on Instagram.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.