Alend Shoresh is a Kurdish farmer and teacher from north-east Syria who was conscripted into fighting Islamic State in 2018: he joined the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) for a year, as was obligatory for men aged between 18 and 30. After he was signed up, he and the other largely Kurdish conscripts were dismayed when they realised that the bus taking them to the front was travelling south, away from their homes near the Kurdish city of Qamishli. After five hours’ driving, the bus started to pass through Arab villages where the men had long beards and short robes that ended below the knee, ‘like Afghan jihadis’, while the women wore veils and were dressed in black. ‘These were places that had been liberated for a year,’ Alend said. Yet ‘Islamic State culture still prevailed.’

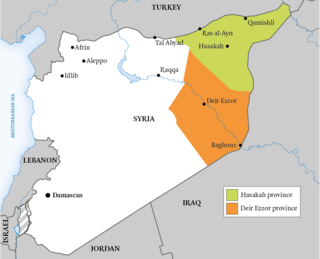

After a short time in a training camp, Alend went to guard a string of checkpoints on a road servicing the oilfields in eastern Deir Ezzor province, four hundred kilometres from his home town. IS, Kurds, Americans and the Syrian government had all fought hard to control this desert area in order to exploit the oil or to prevent their enemies from doing so. The oilfields were close to the last towns and villages held by IS, whose five-year caliphate once stretched across eastern Syria and northern Iraq. IS had lost its metropolitan strongholds – Mosul in Iraq and Raqqa in Syria – but its fighters were still able to slow down the SDF in Deir Ezzor using a mix of snipers, mines, booby traps and suicide bombers. Alend was appalled by the frequent dust storms: sometimes they couldn’t see advancing IS fighters until it was too late. Once, he and four other Kurds manning an observation post were attacked by IS under cover of a dust storm, and three of them were killed. The wife of one of the dead men had given birth on the day of the attack; Alend couldn’t call her because her husband had no phone. He says it would have been better for the dead man’s family if he had ‘been killed defending his town or house and had not died in the wastelands of Deir Ezzor’. Alend himself would willingly have fought in his home territory, which was then under Turkish assault, but it made no sense to him to risk his life defending an area whose people sympathised with IS, hated the Kurds, and had attacked the southern outskirts of Qamishli a few years earlier.

The military defeat of IS was brought about in large part thanks to the Kurds. They supplied the majority of the infantry for the fifty thousand-strong SDF, which fought with close air cover support from the US, along with American weapons, ammunition, money and special military forces. But American backing faltered as IS approached defeat and Trump declared his intention to withdraw from the Syrian ‘mess’ and restore the US’s traditional alliance with Turkey. The prospects for the Kurds is likely to improve under Biden, who will be less co-operative with Turkey than Trump, but they are still surrounded by enemies.

Alend describes once trying to explain to an American officer the political facts of life of the region as the Kurds see them. He was guarding a checkpoint close to an American base and reading a book when a military vehicle stopped nearby. An American officer got out and asked him, through a translator, what he was reading. Alend said he always read novels because he was unhappy in a place from which he felt alienated and was only there because he had been conscripted. ‘But you’re doing something great,’ the officer said. ‘You’re fighting Islamic State.’ ‘Fighting IS is not my job,’ Alend replied. ‘It is yours. I am here to liberate the people of this area, but they do not accept me at all and, when they have a chance, they will kill me.’ He told the officer that the local population was full of IS ‘sleeper cells’ and didn’t accept the US presence either: ‘in the Deir Ezzor countryside, they don’t say “American soldiers” or “troops”, they say “the pigs” and “the dogs”.’ The officer drove off without another word.

IS didn’t go down without a fight. Outnumbered and under heavy bombardment, they fought ferociously and skilfully, inflicting heavy losses. The SDF say that 11,000 of their troops were killed and 23,000 wounded over four years. Abu Fahed Khesham, a 35-year-old Arab commander in the SDF, who, like everyone else interviewed for this article, didn’t want his real name published, led a brigade in Deir Ezzor between 2017 and 2019. Like many caught up in the Syrian conflict, he had become a professional soldier, prepared to fight for various factions in the civil war: before joining the SDF he had fought Assad’s government in Idlib and Aleppo as part of the Free Syrian Army. But combating IS in Deir Ezzor was harder. Early on, he and his men were caught in an ambush: ‘We lost seventeen of our comrades in an open desert area with a few scattered, half-destroyed mud-built houses.’ His group of fighters were setting up observation posts when IS opened fire on their vehicles at long range. A suicide bomber on a motorbike got close and blew himself up, killing six SDF fighters. Another assault followed, from two sides, forcing the SDF survivors to fall back. ‘It was early in the morning when we retreated,’ he says, ‘and we could only collect the bodies of our fighters in the evening after coalition aircraft bombarded IS and pushed them back.’ He wanted to retrieve the bodies because IS routinely mutilated them.

IS relied heavily on guerrilla tactics, as it still does. A highly effective weapon is the mass use of IEDs. As the SDF advanced into the last IS strongholds around the village of Baghouz, Abu Fahed was badly wounded by a booby trap: ‘I was walking slowly up a hill at night to get a better signal for my mobile,’ he recalls. ‘I stepped on a wire under loose soil linked to a mine a few metres away.’ He lost his left eye and his jaw was shattered; he had difficulty eating and drinking for a year. Even so, he was back fighting in the area around Baghouz six months later. The village finally fell on 23 March 2019, provoking self-congratulatory messages from Trump and other world leaders exulting over the destruction of the IS caliphate. Belief in its defeat was reinforced when the caliph, Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi, blew himself up with a suicide vest on 27 October that year after he was trapped in a tunnel under a house in north-west Syria during a raid by US special forces. The fact that he died so far from the IS heartlands was evidence that the movement had no safe places left.

Yet IS was not as dead as its enemies hoped. Always better suited to guerrilla warfare than to holding fixed positions, which were vulnerable to US airpower, its leaders had foreseen the caliphate’s collapse. They had prepared hideouts and weapons dumps in the deserts of eastern Syria and western Iraq. By the end of 2019, many IS leaders were dead. But among those who survived were some of the most experienced, often Iraqis who had been involved in the Sunni Arab jihadi upsurge following the overthrow of Saddam Hussein in 2003. Even though the caliphate is over, in the tribal society of eastern Syria IS cultural norms live on. They are enforced with the killing not just of Kurds and those associated with the SDF, but through the punishment of secular and non-practising Muslims, of people who have sex outside marriage, or sell cigarettes, or deal in drugs, or fail to pay zakat – a traditional charitable tax – to IS. In parts of the countryside around Deir Ezzor and Raqqa, the SDF rules during the day and IS by night.

The political landscape changed in IS’s favour when the US-Kurdish alliance withered. In October, Trump gave the green light to a Turkish incursion into Rojava, the triangle of Kurdish-controlled territory in north-east Syria, forcing Kurds and Arabs to flee, but allowing only Arabs to return. Syrian Arab jihadi militiamen, the cutting edge of the Turkish advance, captured the border towns of Ras al-Ain and Tal-Abyad and a stretch of the main east-west highway, almost cutting the Kurdish quasi-state in two. The SDF are trying to preserve what is left of it through two shaky ceasefire deals: one with Turkey (sponsored by the US) and one with the Syrian government (sponsored by Russia). Northern and eastern Syria have become even more of a kaleidoscope of rival factions than ever. The SDF are still the strongest single presence, but there are American patrols in some areas – after Trump mercurially reversed the US withdrawal – and Russian patrols in others. Detachments of Syrian government troops act as buffers against another Turkish invasion. There are skirmishes along the front line between Kurdish forces and jihadi militiamen who loot and sell Kurdish-owned houses.

IS feeds off this chaos, partly because fighting it has become less of a priority for its many but increasingly divided enemies. SDF units have moved from Deir Ezzor and the surrounding provinces to confront the Turkish-backed invaders. Even before this shift, IS was launching an increasing number of hit-and-run attacks. The area around Baghouz remained unsafe, so did the road from the Kurdish cities in the north along which the bus carrying Alend and the other unwilling Kurdish conscripts had driven in 2018. In April 2019, just after the last IS holdouts were captured, a Kurdish friend of mine approached a checkpoint on the road near one of the oilfields. There were two lanes for vehicles, a faster one for the SDF and those associated with them, and a slower one for civilians, involving more rigorous security checks. My friend was in the fast lane when ‘suddenly two motorcycles, which were in the long line of vehicles beside us, moved out of it and a man on one of the motorcycles got out a gun from under his robes and started shooting at a vehicle with SDF men in front of us.’ The vehicles scattered in panic and my friend drove straight to the nearest SDF security police post. He learned later that two SDF men at the checkpoint had been killed and three wounded.

Anyone wearing jeans or driving a large modern vehicle of the kind favoured by SDF officials, usually white in colour, is likely to be attacked. The safest way for non-locals to travel in this part of Syria is to wear traditional Arab dress and drive a beaten-up car in the company of local tribesmen. A farmer in Deir Ezzor, who gave his name as Abu Dahham, says that although the ‘Arabs here are still influenced by IS and look at Kurds as disbelievers and pagans’ the support for IS in the area doesn’t derive only from religious and ethnic hostility but from a struggle over who profits from Deir Ezzor’s oil. When Assad’s forces withdrew from the oilfields seven years ago, the insurgents – at first in the shape of the Free Syrian Army and the Nusra Front, then part of IS – gained immediate popularity by sharing oil revenues with local people. This produced a radical social transformation. ‘Many traders and officers close to the regime left the area,’ Abu Dahham says, ‘leading to chaos and a security vacuum.’ Those who took over were people with little education who had demonstrated against the regime in 2011 and later became commanders in the Nusra Front and IS. ‘They were illiterate and working in agriculture and as shepherds, often in debt,’ he says. ‘And suddenly they had millions of Syrian pounds, not just in their pockets, but in big bags in which they once used to store wheat and barley.’ Just imagine, he says, going from deep poverty to being a super-rich commander of a military group. After it split from the Nusra Front, IS continued to share the money from oil sales with local tribespeople to retain their loyalty. The fact that Kurds and their Arab proxies don’t do this provokes daily street protests as well as escalating attacks. The demonstrators, who burn tyres and block roads, aren’t just complaining about being out of pocket: they say there is ‘no petrol and diesel available for our cars and heaters’.

Raqqa was the effective capital of IS in Syria until its capture after a four month-long siege in October 2017. By the time the siege ended, almost the entire city was in ruins, the buildings still standing pockmarked with bullet holes and scarred by shrapnel. When I was there the following year everyone spoke ominously of IS ‘sleeper cells’ waiting to strike. At the centre of the city was a space enclosed by iron railings with spikes on top which IS had used to display the heads of those it executed. Gunmen and kidnappers made the city unsafe for foreigners. There was a water shortage, no street lighting and no electricity.

People I’ve spoken to in Raqqa say that conditions have improved somewhat over the past year. Dozens of restaurants and cafés have opened and solar-powered street lights make it less dangerous to walk at night. Foreign aid organisations and NGOs have flooded in, providing services and rebuilding schools and clinics. They also provide jobs that pay better than anything Syrian organisations can afford. Residents cite the example of the hospital run in part by Médecins sans Frontières, which pays salaries ranging from $300 to $1500 a month; another hospital, run by Raqqa City Council, only pays between $90 and $150. Yet the improvements are striking only when you consider the previous level of destruction. A local contractor says that more than half the city is still in ruins, though this is ‘down from 80 per cent three years ago’.

What are the chances of IS making a comeback in Syria? All sides, Syrian and foreign, say they are against IS but they may privately calculate that its total elimination is not in their interests. ‘I met many people in Raqqa and Deir Ezzor this week,’ someone who frequently travels to both places says, ‘who are upset because they say the SDF is trying to keep the fight against IS an issue in the eyes of the world by turning a blind eye to their sleeper cells.’ There is a strong whiff of Middle East conspiracy theory in such suspicions: an SDF commander in Raqqa once told me that he and his men were endlessly called out to investigate ‘sleeper cells’ that turned out to be mythical. But one Raqqa resident talks of the French teacher, Samuel Paty, who had shown his pupils cartoons of the Prophet Mohammed and was decapitated by an IS supporter. The SDF refused to investigate the demonstrations in Raqqa in support of his killer. ‘The SDF will make us victims of IS again to get support from the US and the anti-IS coalition,’ he concluded. Many Syrians suspect that the Pentagon, too, finds a continuing IS threat useful as a justification, politically saleable to the American public, for continued military intervention in Syria. The Americans can also see the advantage to them of the fact that many IS attacks are in Syrian government-held territory. According to the Syrian Observatory for Human Rights, IS has killed 1010 government soldiers and supporters in the area west of the Euphrates since March 2019. On 30 December, IS fighters ambushed buses carrying Syrian soldiers and paramilitaries, killing 37 of them.

It’s unlikely that IS will ever be able to resurrect itself as it once was. It is too feared; it made too many enemies. It has lost the advantage of surprise and probably of covert support from foreign governments. But this doesn’t mean that Sunni Arab jihadi fundamentalism, not very different from IS in beliefs and behaviour, is finished. Syrian Arab militiamen, paid for and under the orders of the Turkish army, who have carried out ethnic cleansing against Kurds and Yazidis in northern Syria, aren’t much different from IS. Both Syria and Iraq are increasingly unstable and impoverished. Both have been badly hit by the coronavirus epidemic, at a time when the Syrian economy is being devastated by American sanctions and the Iraqi economy by the fall in the price of oil. As the chaos deepens, IS has a chance, probably in some new guise, to rise again.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.