In the opening scene of his television series Civilisation (1969), Kenneth Clark admits that while he can’t define exactly what civilisation is, he knows it when he sees it. The camera pans towards Notre Dame Cathedral as if to say ‘this is it.’ For Clark, the artistic achievement of the medieval period was European. The sophisticated cultures flourishing simultaneously in West Africa weren’t part of the story. Despite recent attempts to challenge the idea that the Middle Ages belong to Europe – including Henry Louis Gates Jr’s PBS series Africa’s Great Civilisations – the eurocentrism of Civilisation prevails. It wasn’t that Clark didn’t recognise the significance of medieval African artworks: he was instrumental in acquiring a 14th-century bronze head from Ife, the capital of the Yoruba people, for the British Museum in 1939. It was simply that he couldn’t conceive of Africa and Europe as belonging to a cultural continuum.

Caravans of Gold, Fragments in Time: Art, Culture and Exchange across Medieval Saharan Africa, a timely, scholarly exhibition with an ambitious catalogue, doesn’t simply redraw the boundaries of what constituted the medieval world, but argues for West Africa’s central importance in the complex systems of trade, exchange and interaction between Asia and Europe. The show, which opened at the Block Museum in Chicago in January 2019, has travelled to the Aga Khan Museum in Toronto and is now at the National Museum of African Art in Washington DC (currently closed, but available online). It spans the period between the eighth and sixteenth centuries, focusing on specific areas in modern day Mali, Nigeria and Morocco. The overlapping historical empires of Ghana, Mali and Songhai in the west, and the Almoravid and Almohad dynasties to the north, are all linked by the Sahara – not a lifeless, inhospitable desert, but an inhabited region with its own cities and ancient knowledge, traversed by nomads for centuries. Over time, some of these nomads, notably the Almoravids, travelled north across the Sahara and settled there, in what is now Morocco, creating a vast empire and, in the process, laying the foundations for cities such as Marrakesh, a citadel of walls and mosques founded in 1070, just as the Normans were laying claim to England.

Arabic accounts provide the earliest written record of trans-Saharan trade. The scholar Ibn Hawqal, who visited Sijilmasa in southern Morocco in 951, testified to its importance as a trading centre. ‘There is,’ he wrote, ‘an uninterrupted trade with the land of the Sudan and with other countries, abundant profits, and the constant coming and going of caravans.’ Convoys of camels laden with gold dust – nuggets were reserved for West African kings – or elephant tusks crossed the Sahara from south to north in order to exchange goods at markets such as those of Sijilmasa. Gold was transformed into dinars, each one stamped with an inscription naming the authority by which they were minted. Coins from the mint at Sijilmasa, famed for using only the purest gold, circulated widely throughout North Africa, Asia and beyond. The extraordinary productivity of the mint demonstrates the importance of West African gold to the bullion-based economies of the Islamic world, which enjoyed privileged access to a trade that eluded European rulers until the later Middle Ages. Hoards of Almoravid coins minted from gold that had crossed the Sahara have been found as far away as Cluny and London.

In return for gold and ivory, traders received salt, textiles and copper – all highly prized and extremely rare – from elsewhere in Africa, Asia and Europe. Salt in particular, used for food preservation but also as a currency in Ghana and Mali, drove the trade of goods across the Sahara. Writing in the 12th century, the Andalusian traveller Abu Hamid al-Gharnati recorded the relative exchange value for gold and salt among the traders: ‘They sell the salt at one weight for one weight of gold, or sometimes they sell it at one weight for two weights or more.’ The artefacts in the exhibition attest to a vast traffic in valuable goods: this was not a region defined solely by the exploitation of its material wealth. A fragment of delicately glazed Chinese Song dynasty porcelain, made sometime between the tenth and 12th centuries, was uncovered at Tadmekka in Mali in 2005; a tiny piece of Chinese silk, also found at Tadmekka, still bears the red threads added on arrival so that it could be attached to something else. Both the porcelain and the silk must have been conveyed to Tadmekka along networks of Islamic trade stretching from East Asia to West Africa. Bronze basins, made in either Egypt or Syria, and dating to the 13th and 14th centuries, can be found in Nsawkaw and Atebubu in Ghana, where they remain highly regarded as ceremonial objects. Their forms, and the decorative flourishes of text around the rim, were imitated by later West African metalworkers. African artists took inspiration not only from Asia but from Europe too. A group of five 12th-century stone monuments, each with carved textual inscriptions, were made in Almería (an Andalusian town in what was then Islamic southern Spain), but have been found in Gao in Mali and were almost certainly commissioned by Malian patrons. They were discovered in a graveyard along with a series of locally made stone monuments similarly inscribed.

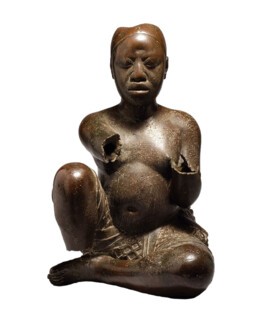

The most extraordinary objects in the show were made in West Africa itself. Several are on loan from the Nigerian National Commission for Museums and Monuments, including the group of ninth or tenth-century copper items discovered at Igbo Ukwu between 1959 and 1964. The excavations revealed around 685 objects across three sites. Particularly remarkable is a large copper-alloy pot. Its trumpet-shaped foot, decorated with alternating blind and open swirling motifs, is the pedestal to a vase, rounded at its centre like an ostrich egg, which curves upwards into a thin but broad rim. A rope of bronze hangs loosely around it, tied at various points in double knots to form an outer openwork shell. The virtuosity is breathtaking and predates anything in Europe approaching its sophistication: Abbot Bernward’s bronze doors for Hildesheim Dom, for example, were commissioned only around 1015. The pot from Igbo Ukwu required three castings to achieve its final form. First, using the lost-wax method, the pot and stand were made as a single piece. The rope-work outer shell and additions were separately cast and then all the parts fused in a third casting, where, unusually, new wax elements were applied to the almost finished bronze. Then, in a high-risk finale, the whole piece was encased in clay and placed in the forge.

Most medieval historians of the trans-Saharan trade worked from second or even third-hand descriptions. Ibn Battuta (1304-68), who travelled throughout the Islamic world, actually crossed the Sahara in order to visit the medieval empire of Mali. He went, like later European travellers to El Dorado, in search of the source of the gold for which the region was famed. But despite the central place of gold in the economies of these West African kingdoms, Ibn Battuta and most other Arabic authorities were ignorant of its source and never discovered the locations of the mines. Those who controlled the resource clearly didn’t want them to know.

But gold there certainly was. Mansa Musa, the 14th-century emperor of Mali, was renowned for his phenomenal wealth. His largesse was evident on a pilgrimage to Mecca in 1324 where, as Al-Umari recorded, ‘he left no court emir … no holder of royal office without the gift of a load of gold.’ On his way he passed through Egypt, where he was said to have been personally responsible for deflating the price of gold. Musa’s wealth was so well known in the Middle Ages that he was depicted on an object produced for a European king: the Catalan Atlas, attributed to the Jewish cartographer Abraham Cresques (1325-87) and commissioned for Charles V of France by his cousin Pedro IV of Aragon. Musa is shown seated on his throne, wearing a gold crown and carrying a sceptre topped with the fleur-de-lis. He holds aloft a brilliant gold disc, which he offers to a camel-mounted trader. The text alongside him states that ‘this king is the richest and most distinguished ruler of the whole region on account of the great quantity of gold that is found in his lands.’ European rulers of the Middle Ages, always in need of ready cash, must have envied Musa’s seemingly endless supply of gold.

Once we start considering ‘European’ medieval art in terms of its materials, the presence of Africa is inescapable. Italy’s trade connections across the Mediterranean, particularly with the Hafsids of Tunis, resulted in a steady flow of gold into its city states. The gold-ground paintings produced in Florence, Siena and other artistic centres are indebted to trade these trade networks. Florins, minted in Florence from the 13th century onwards, were one of the earliest gold currencies to circulate in late medieval Europe. In artists’ workshops, these coins of African gold were hammered into gossamer-thin leaves and applied to the background of countless panel paintings from Flanders to Ferrara. Ivory, or ‘white gold’, was similarly imported to Asia and Europe from West Africa across the Sahara. A 13th-century boom in ivory carving, centred on Paris, created a flourishing trade in elephant tusks from the African savannah. These tusks were larger in diameter than those from Asia, and were highly prized by Parisian sculptors who used them for religious diptychs or carvings of the Virgin and Child. The form of the tusk is echoed in the exaggerated tapering and curvature of some of these pieces.

There is no lack of evidence for the singular importance of West Africa in the trade of gold or ivory to Asia and Europe in the Middle Ages, or for the crucial role played by towns such as Sijilmasa. Yet paradoxically there is little surviving archaeological evidence in some of the centres for the existence of such a trade, including Sijilmasa itself. All that has been discovered there is a single ring dating to the ninth or tenth century: a band, just under two centimetres in diameter, of two twisted wires suspending between them a continuous ripple of gold.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.