It began with the beheading of a god. In a dispute over theological primacy, Brahma – traditionally identified as the creator – insulted Shiva. The offended deity poured all his anger into the creation of a new god, Bhairava, who emerged wreathed in fire and shining like the god of death. He tore off one of Brahma’s heads, which immediately attached itself to his hand in the form of a begging bowl made from a divine skull. Rather than seeking vengeance on Bhairava, a penitent Brahma rejoiced: the encounter with divine violence shattered his self-regard, which had grown to eclipse the ultimate truth. He was, suddenly, enlightened.

Near the entrance to the British Museum’s Tantra exhibition (until 24 January, temporarily closed) sits a late sixth-century stone statue of Bhairava, his eyebrows arched in fury, skull cup in one hand, trident in the other. The statue provides a clue to curatorial intentions. The publicity material for the exhibition states that this is the first historical presentation of Tantric visual culture in Britain. The important word is ‘historical’: the works selected and the scrupulous sobriety with which they are treated represent a coded critique of the Hayward Gallery show on the ‘Indian cult of ecstasy’ in 1971, which, inflected by countercultural predilections and fascinated by sexual deviancy, set the tone for Tantra’s popular reception in Britain. Imma Ramos, the BM’s South Asia curator, is less prescriptive, preferring to talk of Tantra as a ‘body of beliefs and practices … above all a form of corporeal spirituality’, as well as a ‘countercultural philosophy’ with a ‘rebellious spirit’. Bodies, living and dead, are imagined, deified, worshipped, cultivated as sources of power and dismembered in terrifying rituals of transgression designed to free the mind.

Tantric practice is bewilderingly diverse. It ranges from relatively conventional devotional acts, such as breath control and repetitions of mantras, to the deliberate ritual transgression of dietary, sexual and caste taboos, or direct genital worship. A practitioner, or Tantrika, is directed to meditate in the charnel ground, among decomposing bodies, or to smear themselves with ashes from the crematorium pyre. Elaborate meditative instructions overlay the Tantrika’s body with a cartography of channels, whorls and lotuses on which gods sit; Tibetan manuals instruct the practitioner to imagine a vast and ramified symbolic cosmos collapsing into pure light, or their own body flayed alive. Stencilled on a wall in the exhibition’s first room is a reminder that Tantra sees the universe as animated by divine female power; female deities predominate, from the sky-dwelling Yoginis, worshipped in open-topped temples – one from Odisha is re-created in the exhibition, the light changing overhead, a litany playing on a loop – to Kali, a hugely popular goddess uniting maternal and destructive qualities. Motifs repeat through the galleries: the skull cup, originally adopted as a begging bowl and libation vessel by cremation ground mystics, passes from deity to deity, acquiring layers of symbolic meaning. Europeans have been especially intrigued by deliberate transgressions – the eating of meat, drinking of wine and, above all, ritual sex – but Tantrikas are often warned that this is the fast and dangerous track to enlightenment.

Visitors might still feel the lack of a clear definition. Tantra isn’t a religion, but it profoundly transformed two major religions, Hinduism and Buddhism. It isn’t about sex, but it’s shot through with sexuality. Its practitioners range from hucksterish wandering mystics to kings, from celibate monks to rock stars. Scholars frequently point to the word’s etymology – it derives from a Sanskrit root meaning ‘to weave’ – to suggest there is something intrinsic about the way Tantra pulls disparate threads together. Some use it strictly to refer to the scriptures called ‘Tantras’, a vast corpus mixing divine dialogue, ritual instruction and metaphysical commentary (some of the earliest surviving palm-leaf manuscripts are on display at the BM). Others argue that as a distinctive category, Tantra only really emerges from the interaction between Western observers and Eastern culture. Yet the recurrence of motifs, the constant return to the body throughout the millennium of history condensed by the exhibition, does suggest a clear internal coherence, perhaps defined against a persistent and more orthodox asceticism. One early Tantric text, the Hevajra Tantra, provides a neat definition of the knot at which it worries: ‘By passion the world is bound; by passion too it is released.’

Any modern presentation of Tantra must be conscious of the opprobrium and condescension that for centuries characterised its reception. Early British fascination – Ramos makes the case that Blake drew on popular illustrations of Kali for his vision of Lucifer – gave way to moralising repulsion and evangelical enthusiasm. The Victorian Sanskritist Monier Monier-Williams described Tantra as Hinduism’s ‘last and worst stage of medieval development’. The instinct to treat it as a kind of degeneration, a ‘lamented supplement’ to pristine orthodoxy, as one scholar of Buddhism has put it, is still common. Reading the work of early British Indologists, it is hard to avoid the sense that they sought in a strictly Vedic, pre-Tantric Hinduism an Indian analogue to Protestantism, one whose scriptural rationalism had been marred by an accumulation of barbaric ritualism. This impulse has been shared at times by Indian reformers and nationalists: the mid-19th-century Vedic ideologue Dayananda Saraswati launched a bitter attack on ‘the trickery of these stupid popes’, Tantrikas who represented everything he thought degenerate about the India of his day. The exhibition prefers to stress the prominence of Kali as a symbol of Indian independence, but also, for India’s colonial governors, as the source of panicked fantasies about the dangers presented by ‘thuggee’ cults. (The ‘thuggee’ panic of the 1830s, which attributed a religious motivation to banditry and unrest prompted by colonial exploitation, has had a long cultural afterlife, providing plots for innumerable European potboilers as well as Orientalist films such as Gunga Din and Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom.)

Many of the works that derive from the BM’s own collections were locked away in its Secretum for decades, accessible only to those whose gender and class supposedly made them invulnerable to corruption. John Woodroffe (1865-1936) was typical of Britons with a penchant for Tantra: by day a judge on the Calcutta High Court, renowned for his severity, he was by night an ardent Tantrika, publishing translations and introductions under the pseudonym ‘Arthur Avalon’. The journey from spiritual emancipation to the politics of liberation isn’t inevitable, of course, but one can’t help wondering how often the two sides of the self met.

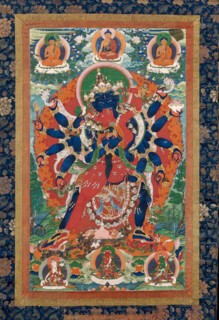

The best artefacts in the exhibitions are in the rooms devoted to the arrival of Tantra at the Mughal court and in Tibet. Mughal paintings evoke serene gardens, which lend their transgressor saints a luminous stillness; a scarlet Bhairavi exults on a corpse in a charnel ground, executed in precise and unruffled lines. The human body becomes a garden full of flowers on which deities rest. A Tibetan thangka (painting on silk) depicts an explosion of colour and light: a wrathful deity and his consort, shown in a carnal embrace, hold implements of war and destruction while skeletons dance around them. The sexual posture, we’re told, represents the union of wisdom with compassion, though when one looks at the thangka it’s easy to forget. Both the Mughal and Tibetan rooms prompt questions. How did an antinomian, transgressive mysticism find fertile soil at an imperial court? That it provided divine legitimacy for rulers, as well as diversion for aristocrats, doesn’t seem sufficient to account for its centuries-long endurance and wide-ranging appeal. Why was it taken up by celibate Tibetan monks, and why do they venerate the mahasiddhas, Tantrikas who gleefully break every monastic rule?

One clue might lie in the way that Tantra’s key symbols shift endlessly between metaphor and reality: the knives and swords of the Tantric deities are methods of breaking through attachment and delusion, but they are also real knives used to flay corpses. The charnel ground is at once the world of material form, the human body, the oppressed nation – and a real crematorium strewn with bones. The skull cup is a begging bowl, or represents non-attachment, or is filled with ecstasy, or with the reasoning mind – and it’s suddenly in front of you, a real skull, of someone who lived like you, and died like you will die. Now drink from it. The effect is vertiginous.

After this, the room devoted to 20th-century ‘re-imaginings’ of Tantra seems tawdry and shallow. It is the most difficult room to make cohere and could be part of another exhibition, about the longer history of the recurrent ‘turn to the East’ at moments of spiritual crisis. Some of the Indian artists might bristle at their inclusion under the label ‘neo-Tantrism’, but their work – along with the austere abstractions of Ithell Colquhoun (1906-88) – is more compelling than the reduction of spiritual liberation to the suburban transgressions of hashish and fucking, as in some of the more popular consumerist material on display. It’s a reminder that the exhibition’s subtitle (‘Enlightenment to Revolution’) is composed of concepts as full of shifting meaning as any skull cup. It would be unfashionable – very 1971 – to ask the more general, transhistorical question that troubled me: what is it about the experience of desire, which can terrify and overwhelm, that leads so many people along the same path, seeking freedom from it and through it? And in a culture which panders to desire above all, what is there left to transgress?

Ramos’s curatorial interventions are subtle. Wherever possible she has stressed the agency of – or at least reverence for – women, though Tantric traditions exist that treat women as convenient tools for male emancipation, to be used and discarded. The strand of 20th-century interest in Tantra evidenced by fascist dilettantes like Julius Evola is mercifully absent. Ramos has been brave in foregrounding heterodoxy and tolerance, illustrating contacts between Muslim mystics and Tantrikas at the Mughal court, quoting in her catalogue essay the 14th-century Kashmiri Tantrika Lal Ded: ‘The lord pervades everywhere,/There is nothing like Hindu or Musalman,/All distinctions melt away.’ This is not a version of history popular with the current Indian government. The exhibition is attentive to historic anticolonial uses of Tantra, but it would be enlightening to know more about the ways in which these dazzling items came to be in the BM’s possession. Of the Odisha temple statues, we are told only that they were ‘dispersed’ between various collections. Not every taboo, then, is broken.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.