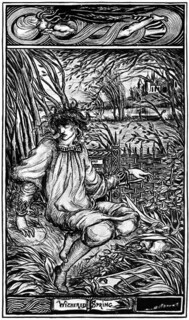

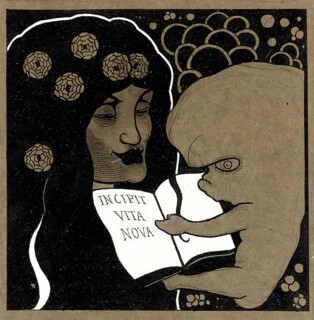

‘Irepresent things as I see them,’ Aubrey Beardsley said, ‘outlined faintly in thin streaks (just like me).’ Beardsley, who died at 25, passed his brief life in the fin-de-siècle milieu of Max Beerbohm and Oscar Wilde. Like them, he was his own artefact. Immensely thin and hollow-eyed with long fingers and a large nose, he seemed to the actress Elizabeth Robins, who met him at a lunch party, to be merely the ‘uncertain ghost of Oscar’. Tate Britain’s exhibition (until 20 September) demonstrates how deceptive the cultivated appearance was, revealing the sheer scale of Beardsley’s industry and the determination with which he pursued his peculiar vision. He had been tubercular from childhood and, as if sensing that his career might be short, his art matured at hectic speed. Its roots were among the Pre-Raphaelites. Burne-Jones was an early champion and the dishevelled androgynous figure in Withered Spring, a drawing of 1891, has the heavy, sensuous eyes and mouth of Jane Morris. A year later, in Incipit Vita Nova, they had gone. An impassive female head with closed eyes faces a foetus with its eyes open. By the following year Beardsley had found his style, monochrome and linear. ‘I take no notice of shadows,’ he explained, ‘they do not interest me; therefore I feel no desire to indicate them.’

A commission from the publisher J.M. Dent to illustrate a two-volume edition of Le Morte d’Arthur, conceived in the style of William Morris’s Kelmscott Press, enabled Beardsley to give up his deadly day job as an office clerk, only to find the quest for the Holy Grail almost as constraining. The endless knights and ladies bored him; something odder and darker was emerging from the Pre-Raphaelite chrysalis. It found its expression in illustrations for Wilde’s banned play Salome, which brought Beardsley fame and notoriety in one go. Despite the publisher’s insisting on a fig leaf here and there, sexual imagery proliferated throughout, from phallic candlesticks to small men with enormous erections. The latter became something of a theme, reaching its apotheosis in the illustrations to Lysistrata, Aristophanes’ comedy about the Athenian women’s sex strike. As Clare Barlow writes in her catalogue essay (Tate, £25), Beardsley’s work includes ‘a striking range of sexual practices’, as well as fantastic, sometimes nightmarish figures of satyrs, hermaphrodites, foetuses and chimeras, several with the face of Wilde and all drawn in needle-sharp, shadowless detail. It is the line, like tight wire, that keeps his outlandish scenes from tumbling into Hieronymus Bosch-like orgies, or erupting into the bawdy romps of Thomas Rowlandson. His theory of line, Beardsley claimed, was his only original idea. Instead of ‘thin lines to express backgrounds and thick lines to express foregrounds’, he kept ‘the same value of line’ in both. The resulting flattened monochrome picture plane gives even the most bizarre scenes an air of cool inevitability.

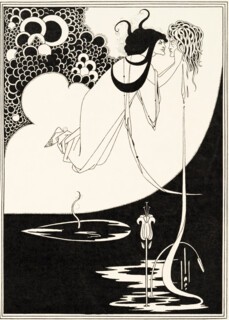

For an artist so possessed by sex, the part it played in his own life remains surprisingly unclear. There was talk of mistresses and a rumour of incest with his sister, to whom he was very close, but for which there is no evidence. Insofar as he bothered to defend himself from allegations of obscenity, Beardsley merely claimed that his drawings were ‘anatomically correct’, reiterating that he drew only what he saw, even if ‘I see everything in a grotesque way.’ Perhaps his physical frailty made him feel like an outsider, an amused or satirical observer of sex. Barlow’s essay is titled ‘Beardsley’s “Obscene Drawings”’, inverted commas presumably meant to distance her from the prudishness of the 19th century, but ‘obscene’ is probably the best word: they are certainly not ‘erotic’. These are scenes of constant titillation, voyeurism and frustration in which desire is torment, there is little sign of pleasure and consummation comes only, in Salome, with death. The Climax shows Salome holding up the severed head of John the Baptist to look him in the eyes, beside the lines: ‘J’ai baisé ta bouche Iokanaan/J’ai baisé ta bouche.’ Below and between the two a phallic lily rises. The Art Journal found Beardsley’s work upsetting, ‘terrible in its weirdness’, full of ‘horror and wickedness’. His reputation was made.

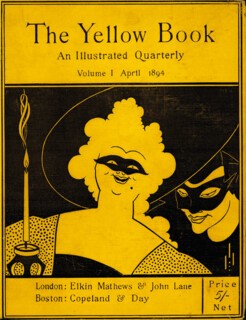

Two months later he designed the cover and four illustrations for the first issue of the Yellow Book, which became the house magazine of the aesthetic movement, and of which Beardsley was art editor. Articles by Henry James, Frederic Leighton, president of the Royal Academy, and other luminaries were overlooked in the outcry at what the Times described as the ‘repulsiveness and insolence’ of Beardsley’s pictures. This time there was nothing overtly sexual in them, but an unmistakeable aura of concupiscence clings to the figures, some masked, one a leering old Pierrot, another a woman out alone at night. The ‘insolence’ presumably consisted in Beardsley’s disregard for academic rules of proportion – heavy heads on drooping bodies or tiny heads above great tents of drapery. His sinuous line was inflected with what would come to be called Art Nouveau, a movement for which the English showed marked distaste. The Yellow Book became another succès de scandale.

Beardsley pronounced himself ‘enchanted’ by the outrage, which made circulation soar, but that was not his main intention. The Yellow Book was conceived as a challenge to the position of illustration as the ‘handmaid of literature’. Words and images were to be on an equal footing, and there was to be ‘no connection whatever’ between the pictures and the text. Beardsley’s style was ideally suited to illustration, but his temperament was not. He was incurably wayward. His Salome was not Wilde’s, which is set in ancient Judea, but a parallel drama taking place in a floating world informed by ‘something suggestive of Japan’. ‘However much I may admire a piece of literary work,’ he said, ‘the moment I am about to illustrate it I am seized with an instinctive loathing to the cause of my woe.’ While slogging away on Le Morte d’Arthur he gave vent to his feelings in a series of Bons Mots, small format collections of the sayings of Sydney Smith, Sheridan and others, published by Dent, which Beardsley adorned with skeletons, Pierrots, angry animals and mythic beasts, wilfully at odds with the subject matter. These anti-illustrations have now been collected by Beardsley’s biographer Matthew Sturgis in Bons Mots and Grotesques (Pallas Athene, £12.99), where they appear alongside Beardsley’s own sayings, making a mosaic of a life in miniature.

In 1895 the frisson of scandal around Beardsley’s set turned to disaster. As the police led Wilde out of the Cadogan Hotel, he picked up a book with a yellow cover. It wasn’t the Yellow Book, but the press assumed it was. Beardsley’s presence at the magazine made it guilty by association. He was sacked and something of the charmed, gadfly character of his career was lost and never recovered. Later that year he was back on the illustrator’s treadmill. Despite his assertion that ‘contemporary illustrations are the only ones of any value or interest,’ he took on two classic texts at once: Pope’s Rape of the Lock and Lysistrata. Both are fully represented in the exhibition and show Beardsley learning to work in two registers at once. Pope benefited from Beardsley’s recent interest in the Rococo, which came out as high camp Art Nouveau. The 19th century’s somewhat sickly view of 18th-century elegance was replaced by figures in vast wigs, soaring up to become trees or merging with elaborately ruched window blinds. Dresses melt into upholstery. Beardsley thus evoked Pope’s combination of refinement and decadence, a suggestion of beauty spots concealing something suppurating. Meanwhile, in Lysistrata, sexual hell was breaking loose.

On a visit to Paris, Beardsley saw Toulouse-Lautrec’s poster for the Divan Japonais, a café chantant in the rue des Martyrs. A red-haired woman dressed in black gazes, eyes half closed, across the waving arms and fiddle heads in the orchestra pit towards the bright yellow light of the stage. Posters on this scale were new, made possible by developments in colour lithography, and for Beardsley they were another way out of the illustrator’s dilemma. In such big advertisements the image had to be dominant. Text was merely for information. If there was ‘a general feeling that the artist who puts his art into the poster is déclassé – ‘on the streets’ – that suited Beardsley, who claimed never to have visited the Royal Academy. He declared the billboard ‘no bad substitute for a hanging committee’, a chance ‘to keep that distance that lends enchantment to the private view’, and took to poster design immediately. Toulouse-Lautrec reciprocated his admiration. The advertisements for the Pseudonym and Autonym Libraries, the Avenue Theatre and others arrive with a bang at the end of the exhibition. Line was still of the essence, but colour amplified its possibilities. Scale also required adjustments. Unlike his earlier work for reproduction, the posters could not be drawn out full size but had to be enlarged. Beardsley was always learning.

In 1894 he made a block print, Self-Portrait in Bed, in which a doll-like head is tucked between voluminous bedclothes under a great canopy, the bedpost supported by a hermaphrodite satyr. It was a rare direct reference to the delicacy of his health, which now began to decline. ‘I believe I am so affected,’ he said to friends, ‘even my lungs are affected.’ On doctors’ advice he and his mother sought changes of air, moving restlessly from Boscombe to Dieppe and finally to Menton, on the Riviera, where he died in the Hôtel Cosmopolitain on 16 March 1898. His reputation, like his career, was left hanging. Opinions of how well it has been served depend partly on one’s age. In the 1960s the Art Nouveau revival and an exhibition of his drawings at the V&A spread Beardsley’s influence across album covers and advertisements. For those of us buying Athena posters in the 1970s, Isolde and The Peacock Skirt were so familiar we grew up thinking he was famous. Yet the forthcoming showing of this exhibition at the Musée d’Orsay will be his first ever exhibition in France, and for the Tate it’s the first since 1923. As Alan Crawford wrote in his ODNB entry, Beardsley has been ‘fragmented’ since his death, parcelled out between academics, curators, collectors of art and of books, and biographers. In its scale and range the Tate show goes some way towards putting him back together.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.