Towards the end of her life, Tove Jansson wrote a novel about two women in love. In Fair Play, Mari and Jonna, two artists, live together but apart. They have separate studios, connected by a corridor. They eat dinner in silence, their books propped up next to their plates. Each night they watch a film, often by a well-known director – Truffaut, Bergman, Visconti, Renoir, Wilder – but sometimes they watch a B-Western in which men are ‘unswervingly honourable to one another’ and which ends with the sound of horns and a performance of ‘My Darling Clementine’. They go on holiday to America and Mexico and to their cabin on an island in the Finnish archipelago, where they argue about Mari’s mother, who, when she was alive, stole Jonna’s tools and got in the way. They get lost out in their boat in the fog. Their lives revolve around small, domestic details. Jonna rehangs the paintings on Mari’s walls, paintings that she’d stopped looking at: ‘Look, here’s a thing of mine and here’s your drawing, and they clash. We need distance, it’s essential.’ It is a kind of marriage, though it’s never called that: they are merely ‘friends’, friends who share a bedroom, who get jealous when one of them has a crush on another woman and who sense each other’s mood by intuition:

‘Is it your glasses?’ said Jonna without looking up from her work. After a while she said, ‘Have you looked in all your pockets? The last place I saw them was the bathroom.’

Mari said nothing. Her steps went from the studio to the library and back again, to the bedroom, to the front hall.

‘Tell me what you’re looking for.’

‘Oh, some papers. A letter. It’s not important.’

Jansson is best known for work very different from this. Her first Moomin book, The Moomins and the Great Flood, was published in 1945, though the character of the Moomintroll appeared before that, in her political satires, and was, she said, inspired by an argument about Kant with one of her brothers. Having lost the argument, she drew the ugliest creature she could imagine and wrote ‘Kant’ under it. She took the name ‘Moomin’ from an uncle who tried to curb her greediness by warning her that a ‘moomintroll’ lived behind the stove. The Kant-Moomin gradually became the more attractive and benign family of hippo-like Moomins and nine books followed. They were a huge commercial hit, spawning dolls, clothes, soaps, mugs, theme parks – though Jansson drew the line at sanitary towels – and made her famous around the world. But her creation wore her down: she ‘vomited Moomins’, she said. Writing the Moomin books, and, from 1954, drawing a weekly Moomin cartoon strip for the London Evening News, took her away from her other work. ‘By the end I was drawing with hatred.’ Even writing to friends became a chore: ‘I have lost my enthusiasm for writing letters after all the years of Moomin business.’ After six years, her younger brother, Lars, took over the strip. She was free to write and to paint, when she wasn’t answering endless fan mail, or writing the personal letters, often with illustrations, she sent throughout her life. A selection of around 160 of these letters has now been published for the first time and translated into English by Sarah Death. Covering the period between 1932 and 1988, they trace Jansson’s life more intimately than any autobiography.

She was born in 1914 to two artists from the Swedish-speaking minority in Finland. Her mother, Signe Hammarsten, known as ‘Ham’, was an illustrator; her father, Viktor Jansson (‘Faffan’), was a sculptor. Her parents had lived and studied in Paris, but brought up their three children – Tove, Per Olov and Lars – in Helsinki, in a house dominated by Faffan’s work (Ham had a small desk in the corner of a room). They spent the summer on various islands in Pellinge, an archipelago in south-eastern Finland. Ham had been one of the first Swedish Girl Guides and taught her children to look at the world around them, to read the direction of the wind, the age of tree trunks, the forms of mosses, clouds, ant-hills. But although it appeared idyllic, family life was fractious. Jansson’s father was more interested in animals, including his pet monkey, than his children (one of Jansson’s brothers hid a photograph of Faffan playing with the monkey so she wouldn’t get jealous). He didn’t seem to think much of women, either. He hosted raucous, drunken, all-male gatherings, which Jansson would observe from a distance, later writing – in the childlike voice she sometimes used – that ‘all men have parties and are pals who never let each other down … A pal never forgives, he just forgets and a woman forgives but never forgets. That’s how it is. That’s why women aren’t allowed to have parties. Being forgiven is very unpleasant.’

Instead, Jansson drew closer to her mother. Her childhood with Ham was, she said, like ‘living together under a bell jar’. She would sit on her mother’s lap as she drew and fantasised about escaping with her. As an adult, she often thought of moving away from Finland, but couldn’t leave her mother behind: ‘It is Ham who keeps me here, because I shall never find anyone whom I can love as much, and who loves me as she does.’ In some of her earliest letters, written while she was just across the border, studying art in Sweden in 1933, she writes: ‘I am a part of you, more so than the boys … You are always close to me.’ When she went to study art in Paris, in 1938, her homesickness got worse: ‘Dearest, sometimes – well, often, I feel quite heartbroken that I can’t be with you.’ She has no secrets from Ham: ‘When I talk to you, at any rate, I find everything just comes spilling out of me!’

In Paris, she encountered many more queer figures than she had come across in smaller, sleepier Helsinki. Her uneasy reaction betrayed an interest she would only acknowledge, to herself at least, much later:

At the piscine I saw a gentleman in leopard-skin swimming trunks and a red cap with a bow at the back loudly hail each man he met with a ‘Vous aimez ces femmes?’ There are some very strange fish here. In the bistro next to Beaux Arts I spent ten minutes listening with growing astonishment to a boy I took for a particularly precocious and cynical 13- year-old – when he got up he proved to be a young lady, somewhat over twenty. I wonder whether I can be bothered to go back to that establishment at all.

She travelled around France and Italy, where she seems to have spent most of her time swimming, visiting museums and churches, and looking at soldiers in ‘swanky uniforms’. In 1939 she returned to Helsinki, and her parents’ home. Her relationship with her father worsened during the war: he supported the Nazis; she drew cartoons for Garm magazine that satirised Hitler and Stalin. They fought about nationalism and about her former lover, Sam Vanni, who was Jewish. In 1942, aged 27, she moved out to a studio. ‘I knew I’d never become a happy person, or a good painter, if I stayed.’ She bought a lynx stole and painted a self-portrait with it slung over her shoulders: she looks haughty, glamorous, free. At the time of the move, she thought she might be pregnant and wrote to a friend that ‘a kind of strange, calm “can’t be bothered” is growing in me, with a strong sense of loneliness and fear. Since I decided to leave the family, everything’s changed, choice of words, thoughts, even tastes.’

Helsinki was miserable during the war, and for a long time afterwards. But behind the blackout curtains there were nights of drinking and dancing. In 1944 Jansson met Atos Wirtanen, a politician eight years older than her and obsessed with Nietzsche. He was the ‘enfant terrible of parliament’, staunchly opposed to the war and soon to become leader of the Socialist Unity Party, which formed a coalition with the Communist Party of Finland. He was divorced and didn’t want to marry again, which seemed to suit Jansson. But their affair caused a scandal and prompted the first of the many anonymous phone calls she would receive, chiding her for her sex life or for selling out by drawing cartoons. Her father was furious about the affair, mainly because he disapproved of Wirtanen’s politics. Jansson was defiant. ‘I don’t want, and never will want, to have anyone else but him. Until now, the thought of potential loves to come has always been thinkable. That’s been a bit sad, perhaps, but also comforting. Now my burning wish is never to have another love affair – it seems inconceivable.’

A year later, the inconceivable happened. Jansson met Vivica Bandler, a theatre director whose half-Jewish Austrian husband was living in Sweden. At first, they didn’t hit it off. Bandler found Jansson too girly, while Jansson was terrified of Bandler. But at their second meeting they danced and drank cut brandy together and stayed on after the other guests had left. ‘I saw a tall dark aristocratic girl with a prominent nose, thick straight eyebrows and a defiantly Jewish mouth,’ Jansson wrote to her friend Eva Konikoff. ‘She is blind in one eye, but the other is clear, dark, penetrating.’ The attraction came as a huge surprise, ‘like finding a new and wondrous room in an old house one thought one knew from top to bottom’. The sex was a revelation, too. ‘I’m finally experiencing myself as a woman where love is concerned, it’s bringing me peace and ecstasy for the first time … I’m new again, liberated and glad, and with no feelings of guilt.’ Her phone calls and, when Bandler was in France, her letters, were similarly orgasmic, causing Bandler to reprimand her (homosexuality was illegal in Finland until 1971, and classified as a mental illness until 1981).

Jansson’s happiness lasted only a few weeks. In France, Bandler took up with another woman and came back colder. ‘We’re no longer in love in that radiant, self-evident way, there are always complications – anguish and irritation and jealousy – and the constant need to conceal it!’ Bandler described Jansson’s affection as like ‘being hungry all one’s life and then suddenly being given dessert, nothing but dessert’. In 1947 Jansson suggested they stopped seeing each other, ‘and definitely this time’. That summer she went back to Pellinge and tried to forget about the affair by building a log cabin on one of the islands. She wrote to Konikoff that Bandler had ‘taken away my anxiety about so many things, Faffan and Ham, my masochistic tendencies in sex, that ambitious sense of duty that’s driven the pleasure out of my painting, and she freed me from the timid, old-maidish prudery that makes people think I am, or pretend to be, naive.’ Even so, a few weeks later she proposed to Wirtanen, her voice prudish and hesitant again: ‘I wonder whether you think it would be a good idea for us to get married … If you don’t want to, we can talk about something else when you get back. There’s plenty, isn’t there.’ He accepted, but suggested they wait until after the parliamentary elections the following year. The wedding never took place. Jansson slept with Unto, a man she knew from art school. ‘I think the thing that touched me most was the fact he made the bed the next morning. No one else has ever done that.’

In 1952, Wirtanen finally decided that he did want to marry her, but she turned him down. It was too late. Jansson, who had previously thought of herself as bisexual, wrote to Konikoff that year:

Another group that’s few in number is the lesbians. The ghosts, as we call them – and as I shall call them in my letters from now on. That might be one of the reasons why Vivica attracted so many people’s attention. It seems to me that the world is full of women whose men don’t satisfy their need for affection, eroticism, understanding etc … I haven’t made the final decision, but I’m convinced that the happiest and most genuine course for me would be to go over to the ghost side.

Jansson had many other euphemisms for lesbianism: ‘rive gauche’, as if all Parisian women were at it; ‘borderliner’; a ‘new line’, ‘tendency’, ‘attitude’. She had become more discreet since her affair with Bandler. (Perhaps because of this, there’s very little in the recent biographies of her, by Boel Westin and Tuula Karjalainen, or in these letters, about Britt-Sofie Fock, a goldsmith with whom she lived for a few years in the 1950s.) Some of this reticence was due to her parents’ reaction. Her father tried to ask her if the rumours were true, but couldn’t say the word ‘homosexual’ because it made him so angry. ‘Ham said nothing. She never says anything. I think she knows. But she doesn’t want to mention it. I can accept that this is right and more elegant. But it feels lonely.’

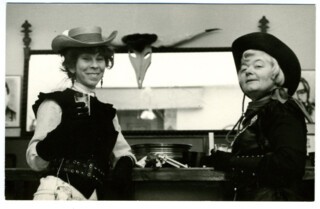

At a Christmas party for the artists’ guild in 1955, she met Tuulikki Pietilä, an engraver and graphic artist, as they both hovered by the gramophone (lesbians felt they had the best taste in music even then). Jansson and Pietilä, who was soon given the nickname Tooti, spent the next 45 years together: they had studios in the same building, separated by a corridor, went on holidays together and shared a bedroom (they had separate beds in their cabin but would ‘slither over and lie close’ in the morning). They shared a love of the Finnish archipelago. ‘I miss those quiet June days when you were piecing together your mosaic or whittling away at some knotty bit of wood and it was possible to listen, contemplate and explore how we felt,’ Jansson wrote to her after they’d been dating for a few months. ‘I dream of islands every night,’ she told Pietilä later, as if islands were a proxy for something else. ‘I read somewhere that ghosts have pronounced island complexes, which interests me,’ she told her friend Maya, who had married Sam Vanni. ‘Some form of identification, isolation trauma, the devil only knows.’

Their island life, though, was becoming complicated, with too many visitors passing through and not enough space to work. When Bandler came to stay with her latest pair of lovers in tow there were ‘major ghost dramatics’, with Bandler ricocheting between the two women, ‘because Lisbeth refused to sunbathe in the same cleft as Nita’. After Faffan died in 1958, Ham became more of a problem too. Jansson felt guilty about leaving her mother when she went on holiday with Pietilä, writing that ‘we’re so close to one another that we can’t really cope with being separated for any stretch of time.’ But when they were all at the cabin in Pellinge, her mother squabbled with Pietilä, ‘in a disrespectfully-gruff-but-friendly sort of way’. It got too much, and in 1963 the couple built a cabin on a more remote island, Klovharen. Ham, who was increasingly unwell, saw the new place as an ‘enemy’. ‘It’s so awful,’ Jansson complained to a friend, ‘these two women I love, one of whom wants to die and the other to live at any price – and I can’t help either without making things worse for the other. Sometimes I think I hate them both and it makes me feel ill.’

In early 1970 Jansson went to Klovharen for the summer. Two months later Ham died. At first, Jansson was so upset she couldn’t say her mother’s name. ‘The summer continues, just as beautiful,’ she wrote, ‘and the work continues.’ A year later The Listener, her first book of short stories, was published. The year after that, her first novel, The Summer Book, came out. It follows a girl called Sophia, her grandmother and her taciturn father over the course of a summer on a Finnish island. The death of Sophia’s mother is mentioned only once. Their days on the island are self-contained. ‘An island can be dreadful for someone from outside. Everything is complete, and everyone has his obstinate, sure and self-sufficient place.’ The chapters read like short stories: a long-tailed duck dies; grandmother sneaks cigarettes; she and Sophia argue about God; they wait anxiously for father to come back during a storm. The landscape has its own life:

On the whole island, there was nothing but rock and juniper and smooth round stones and sand and tufts of dry grass. The sky and the sea were veiled by the yellow haze, which was stronger than sunshine and hurt the eyes. The waves heaved in towards land like hills and curled into breakers at the shore.

After Ham’s death, it was as though a heavy weight had been lifted. ‘I’ve a feeling I’ve been worrying about Ham all my life,’ Jansson wrote, ‘and sometimes it’s such a burden.’ But her mother haunted her fiction, in the figure of the grandmother in The Summer Book, or in Fair Play where Mari’s mother is the subject of disagreements between the two women. In ‘The Great Journey’, a short story in her collection Art in Nature, a lesbian decides to go on holiday with her mother instead of her lover. ‘I’ll steal you from Papa … I’ll build you a castle where you shall be queen.’ By contrast, in 1971 Jansson and Pietilä went on a eight-month round-the-world trip. They drank in pubs on the King’s Road in London, though they failed to find any ‘ghost places’ there, and hoped to have better luck tracking down lesbians in Amsterdam. They then headed off to Japan, Hawaii, America and Mexico.

More books came, but slowly. In 1982 Jansson published The True Deceiver, a taut, sparse thriller in which Katri, a woman derided as a ‘witch’ by her village, moves with her brother into the house of Anna, a successful writer of children’s books. ‘It just gets harder and harder to write,’ she told a friend as she worked on the novel, writing and rewriting it over four or five years. Her last book, Fair Play, appeared in 1989 when she was 75 years old. Shortly afterwards they abandoned life on Klovharen – they could no longer haul their boat up to the shore and the cabin had been broken into several times – and moved to Helsinki for good. Even worse, after a lifetime of loving storms, Jansson now found them frightening. ‘That felt like a betrayal – my own.’

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.