He had two days to prepare. We’d been thinking about it for a year. Four thousand infantry had to be organised. Eight hundred cavalry. Mules, carts, munitions, medical services. A cannon. He was disappointed, having hoped ten thousand would follow him. There were two of us. We left from the same place, Piazza San Giovanni in Laterano, in Rome. He in 1849. We in 2019. On 2 July. The white mass of the basilica loomed in the dark, huge stone apostles silhouetted against the sky. He set out at sunset and had his men march through the night. No smoking was allowed. Orders were whispered down the lines. The enemy must not get wind of their movements. Our main enemies, we reckoned, would be traffic and heat. The forecast was for 38 degrees, so it was tempting to do as they did and leave in the cool of the night. But to walk along fast roads in the dark would be suicidal. So we left at 4.30 a.m., hoping to cover twenty miles before the sun was high.

The square was dead. No one had come to see us off. Garibaldi and his men were cheered by a big crowd. The American journalist Margaret Fuller was there. ‘Never have I seen a sight so beautiful,’ she reported, ‘so romantic and sad … I saw the wounded … laden upon their baggage carts … I saw many youths, born to rich inheritance, carrying in a handkerchief all their worldly goods.’ Garibaldi, Fuller said, was wearing a white tunic. Other observers have him wearing the red shirt he made an emblem of the struggle for Italian nationhood and a poncho, a relic of his time in South America. His Brazilian wife, Anita, six months pregnant with her fifth child, followed him on horseback at the head of the column.

The city of Rome and the territory known as the Papal States, stretching north to Bologna, east to Ancona and south to Terracina, declared itself a republic on 9 February 1849. It was the last of the ephemeral states that emerged across Europe after the Revolutions of 1848. The hope was to make Rome the capital of a united Italy: the country was then fragmented and largely governed by foreign or despotic powers. Initially, Pope Pius IX had looked favourably on the movement for national unity, even encouraging patriots to think of him as a future monarch and granting his subjects a constitution in March 1848. But, frightened by the clamour for further reform, he became hostile. When his prime minister was assassinated in November 1848, Pius fled the city for the protection of the king of Naples and called on Europe’s Catholic powers to reconquer Rome for him. At once, the Austrians moved south from the territory they held in the Veneto to crush the rebellions in Bologna and Ancona. But, ironically, it was France, a newly formed republic with a constitution committed to defending other republics, which set out to retake Rome for the pope; a French army disembarked at the port of Civitavecchia on 25 April.

Thousands gathered to defend the city and the dream of a nation-state. The most prominent was Giuseppe Garibaldi. A seaman by trade, he had been sentenced to death for insurrection in 1834 and spent years in exile in Brazil and Uruguay, where he was a courageous and effective fighter for liberal causes. Encouraged by developments in Europe, he took advantage of an amnesty to return to Italy with sixty comrades in June 1848. Wandering around central Italy gathering volunteers, he was in Bologna in November when news came that Pius had fled from Rome. He hurried south and spent some months in Rieti, forty miles north-east of the city, training 1500 men who would be known as the First Italian Legion. On 27 April 1849, they marched into Rome, just in time to play a decisive role in routing the French army on 30 April, then left the city again to defeat a Neapolitan army on 9 May. It was the first time Italian volunteer forces had beaten professional foreign armies in the field.

The French sent reinforcements and attacked again in June with 30,000 men and 75 cannons. Under constant bombardment, and with great loss of life, the city resisted for a month before the walls were breached. In the hours between the realisation of certain defeat and the entry of the French into the city, Garibaldi addressed a crowd in St Peter’s Square:

Fortune, who betrays us today, will smile on us tomorrow. I am going out from Rome. Let those who wish to continue the war against the foreigner, come with me. I offer neither pay, nor quarters, nor provisions; I offer hunger, thirst, forced marches and all the perils of war. Let him who loves his country in his heart and not just with his lips, follow me.

Garibaldi had extraordinary charisma. ‘I could not resist him,’ one man who hadn’t been planning to volunteer admitted. ‘We all worshipped him, we could not help it.’ What they worshipped was his total dedication, his calmness in crisis, his decisiveness, his readiness to fight alongside them. They responded to his belief in freedom, reflected in the outlandish clothes he wore, his impatience with convention, and his conviction, for all his foreign travels, that the nation-state was the prerequisite of individual liberty. When my partner, Eleonora, and I set out on our journey, support for the nation-state seemed a reactionary position. Talk of national sovereignty in Italy has been hijacked by those who blame immigration for everything and preach hatred and closure. It seemed a good moment to compare Garibaldi’s idealism with contemporary reality.

Two of his officers, Egidio Ruggeri and Gustav von Hoffstetter, a German volunteer, kept and then published diaries of the march. In 1899, Raffaele Belluzzi collated their versions, adding details from letters, unpublished manuscripts and interviews with surviving witnesses. In 1907, G.M. Trevelyan added information from other correspondents. But there’s no agreement on the route taken in the first two days, perhaps because Garibaldi’s main concern was to fool everyone about where he was going. By leaving from Piazza San Giovanni, he gave the impression he was heading south, but by dawn his men were in the hillside town of Tivoli, due east. No one is sure where they changed direction. It was dark and the men marched in the dust thrown up by those in front of them. Garibaldi, Hoffstetter tells us, told no one of his decisions. He was afraid of informers.

Nobody leaves Rome on foot these days. There are no footpaths, only short stretches of cycle track. Once we’d crossed the railway lines near Termini station, beyond the monuments and grandeur of the centre, the cityscape took on a gloomy post-industrial feel, occasionally relieved by elegant umbrella pines. As the sun rose, we got our first glimpse of the distant hills, which Garibaldi knew he had to reach fast, to have a defensible position in case of pursuit. We were encouraged. They didn’t look all that far away. But beyond the ring road there were no more pavements. We had to press ourselves against crash barriers as trucks rumbled past inches away. Since it seems impossible to buy detailed paper maps in Italy, we had bought a hiking app that seeks out every possible pedestrian route. It couldn’t find one here. Brambles reached across the crash barriers. We walked on detritus: broken glass, roadkill, syringes, cans, condoms and plastic.

Tivoli, Hoffstetter writes, is ‘surrounded by woods’, ‘the sacred groves of ancient times’. He was a cultured man. At 7 a.m., alerted by an advance party of cavalry, the citizens came out to greet the soldiers, bringing bread, meat, wine and fresh water in abundance. Then the men slept in the woods outside the walls, while Garibaldi and his staff set about organising them into two legions of 1800 men, each divided into three cohorts, divided in turn into six centuries. Already there had been scores of desertions.

How I sympathise! In the early afternoon, with the sun at its zenith, having zigzagged across the torrid plain, past sandpits and stone quarries, across rivers reduced to a trickle, taking occasional refuge in the shade of a fig tree, we tackled the steep slope to Tivoli. The towns of central Italy are mostly at the top of hills, and that suited Garibaldi because of their defensive potential. I was quite dazed when we finally entered the shade of the narrow streets, heart racing. Garibaldi was there to greet us. A small, behatted bust, no doubt long removed from some more prominent place, was hidden away in the playground of the public gardens. Yet we noticed it at once: the flowing hair, deep-set eyes and thick beard. Across the road, on the wall of a deconsecrated church, a plaque read: ‘Terror of his Enemies, Admiration of the People, Garibaldi rested here with his brave men, July 3, 1849.’ We rested too. We found our B&B, gave up trying to explain to the landlady that we had walked from Rome and instead listened to her detailed instructions for parking the car.

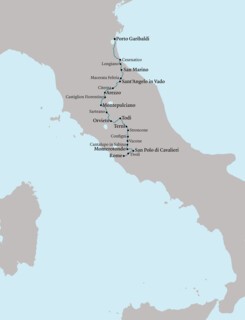

Our route in the coming weeks meandered back and forth, east and west but generally north through Lazio, Umbria, Tuscany, Le Marche and Emilia-Romagna. We didn’t pass through the most famous places, or the most beautiful. Garibaldi had left Rome hoping he could reignite the patriotic revolution in the provinces. When he realised that he was nursing a dying ember, he decided to make for Venice, where the last of the revolutionary governments was still holding out against the Austrians. But there were hundreds of miles and countless enemies – one French army, one Neapolitan army, one Spanish army and four Austrian armies – between him and Venice, and his men were ill equipped and demoralised.

In such circumstances you avoid all military engagement. Set off one way at twilight and switch direction in the night. Be unpredictable. Use the roads one minute, paths the next. Change your baggage carts for mules so you can tackle any terrain. Send bands of cavalry thirty miles in every direction and have them spread rumours you’re heading that way. Always order more rations than you have men. Garibaldi was a genius of complex organisation and systematic fake news.

At 5 a.m. we set out east and south, as if heading across the Apennines to the Adriatic (where the Spanish army was waiting), but then turned abruptly north and steeply uphill along tiny paths and mule tracks, through thick woods, dry heath and rocky spurs, to the charming village of San Polo dei Cavalieri, two thousand feet above sea level, where the adolescent who served us our coffee looked more than ready to forsake his summer job for a desperate military campaign. There were scores of teenagers among Garibaldi’s troops, French boys in particular. He thought them excellent soldiers; fervent idealists, they never complained.

No sooner had the Garibaldini dragged their heavy cannon to San Polo than they had to trundle it down again, along a ridge to the town of Marcellina, before circling back towards Rome and the towns of Montecelio, Mentana, Monterotondo. Celebrating his 42nd birthday with a cigar, Garibaldi was close enough to see the dome of St Peter’s in the sunset, and cheered himself with the thought that he had thrown his enemies off his track. The French and Neapolitans were looking for him south of the city. The Spanish were searching for him on the other side of the Apennines. The Austrians hadn’t yet learned of his escape. Even we, who had studied this route for months, were struggling to keep up.

We had promised ourselves we would do the walk in the same time as the Garibaldini. We had Omni-Freeze shirts, and sweat-wicking underwear, super-technical backpacks and expensive trekking shoes. Their red shirts and long trousers were made of wool. We didn’t have to carry our food tied with string round our necks – loaves of bread, sometimes a roast chicken. Or trail a herd of bullocks behind us and slaughter them in the dark. They were carrying the worthless paper money of the extinct Roman Republic: we had credit cards and smartphones. We didn’t have to negotiate loans with the local authorities in order to buy rations or persuade monks to supply barrels of wine.

But these men were among the last never to have used motorised transport and were accustomed to walking in a way we couldn’t be. Shattered by the heat, the hills, the rocky paths, we stumbled up steep slopes to dusty towns. On arrival, clothes had to be washed immediately, and dried before dawn, because we were only carrying one change. Garibaldi insisted his men keep their red shirts clean, even when water was in short supply. It was important to look like a regular army, not a rabble. For the same reason, it was essential to stop the men looting or stealing. Offenders were shot. Beyond the military war there was the war for hearts and minds, and here the main enemy was the Church, the priests who held the peasants in their grip. In all his years of campaigning for a united Italy, Garibaldi later reflected, not a single peasant volunteered to fight with him.

We were walking due north now, up the east side of the Tiber to Passo Corese, Ponte Sfondato, Poggio Mirteto, Cantalupo, Vacone, Configni, Stroncone, Terni, day after scorching day. Olive groves, vines and peach trees, oak thickets and stone farmhouses. A dusty earthiness enveloped us. An old man hoed between rows of tomatoes in the twilight; a woman with her hair tied back watered zucchini at dawn. At the heart of every little town was the church. And on the roads approaching those towns, monasteries, convents and shrines. For every bust of Garibaldi, there were ten of forgotten bishops and popes, scores of Madonnas and crucifixes. The churches themselves presented the drama of sin and hell and maybe redemption in their frescoes and twisted Christs. Invariably, a patron saint was shown holding a model of the town and offering it to the Almighty. God trumps politics. Change is evil. If the priest told you Garibaldi was a devil, you would believe it. Eleonora has three aunts who are nuns. In Bari, Rome and Naples. ‘They still believe Garibaldi was demonic. They’re still convinced he sacked the convents and raped the novices.’ When occupying the grounds of a monastery – they were convenient places for his men to sleep – Garibaldi would set a guard on the vegetable garden so that no one would be tempted to steal from it. One priest remembered taking a flask of wine to him; he insisted on paying for it. ‘People listen to me and the following morning they’re saying confession,’ Garibaldi complained.

In the piazza of Poggio Mirteto we found this plaque on a stuccoed wall:

Here in the house of the Lattanzi family,

ANITA GARIBALDI,

from 6 to 7 July 1849

was lovingly welcomed

and found rest and solace.

In her heroic heart,

together with the throb of motherhood,

the dream of Rome lived on.

And perhaps, like the light of the setting sun

she foresaw her death.

‘She was 28 years old and slight of build,’ Hoffstetter says of Anita, ‘but you could see at once she was an amazon.’ She had fought beside Garibaldi in Brazil and Uruguay and now, though pregnant and suffering from malaria, she refused to stay behind. These words engraved in the old stone moved me quite unexpectedly, as though the figures we were shadowing were still there behind that shuttered window. But the last line of the inscription – ‘nell’anno Garibaldino X dell’era Fascista’, ‘heroic year ten of the fascist era’ – tells us the plaque wasn’t put there till 1932, and was part of the fascist attempt to appropriate Garibaldi’s story.

We were growing stronger, finding the hills easier, and the heat. Our app was performing better too, proposing pleasant paths away from busy roads. One morning, in a meadow of Umbrian flowers, grasshoppers leaping over our feet, blue butterflies blowing around our faces, feeling the pull of the slope inviting us towards a distant campanile, I began to understand the consolations of Garibaldi’s men. They were in life, and in it together. ‘They danced together in the bullets,’ Hoffstetter reported, incredulous, of an earlier battle.

Initially, Garibaldi had imagined they might find a town where they could raise the tricolour of Italian independence and defend it against all comers. Todi, he thought, might be the place: eighty miles north of Rome, dramatically isolated on a steep hill, stoutly walled. As elsewhere, a band played to greet his men. But the town’s leaders had no stomach for a fight. They didn’t want their homes and churches razed to the ground. The Austrians were close by to the north. The French were approaching from the south. Garibaldi didn’t insist. In another unexpected move, he travelled west over the high plateau to Orvieto, arriving just in time to eat the plentiful rations that the French had ordered in advance, then leaving the town travelling north, just as the French marched through the gate on the other side. He knew they couldn’t follow him into Tuscany, which was under Austrian control.

Garibaldi believed the people of Tuscany would be better disposed towards him than those in the Papal States, who had been cowed and dumbed, he thought, by centuries of Church rule. The Tuscans were more modern, more liberal. Is anything of this left today? Certainly the heart lifts at Tuscany’s rolling hills and picturesque arrangements of pines and cypresses in romantic silhouette around hilltop farms or churches. Certainly the vowel sounds and cadences shift and soften. In the countryside the people greet you with a wave as they pass by in their SUVs. But in the towns they have seen too many tourists, and the generosity we found in Lazio and Umbria froze into snootiness, even hostility. The prices doubled.

Garibaldi was disappointed too. His welcome in Montepulciano had been so enthusiastic that he printed an appeal to the Tuscan people inviting them to rise up and join him. ‘We offer a nucleus for whoever is ashamed of the dishonour, humiliation and adversity of our Italy.’ But people weren’t ashamed, or not ashamed enough to act. From that moment on, the Garibaldini knew they were simply on the run. They also knew that if caught by the Austrians they would be shot, since they were not recognised as a legitimate army. Desertions increased. Senior officers disappeared. When the strategic town of Arezzo refused to let them enter for fear of Austrian reprisals, it seemed possible that the army would melt away.

How can inevitable defeat be turned into moral victory? Each evening, we read up on the next day’s events: an Austrian spy captured, a monk who set the monastery dogs on an officer, Anita in a huff when Garibaldi seemed taken with the Tuscan women. One book contained the communications between the Austrian commanders who were trying to pin Garibaldi down. Their low opinion of the Italians is all too evident: Garibaldi’s men were thieves, rabble, dregs. But as he continued to elude them, that initial confidence dissolved into bewilderment. They couldn’t understand how a mere hothead could lead them such a frustrating dance. After the move west to Orvieto they were sure he was heading for the Tuscan sea and set off to intercept him, but he popped up to the north in Sarteano. They thought he must be intending to occupy Siena or even Florence and called for reinforcements. Garibaldi’s horsemen were everywhere. But the main body of men moved sharply east again, marching at night in heavy rain. General Stadion complained that even when he managed to get close, his men were too tired to attack.

Eventually, it became a race across the high Apennine chain: Garibaldi hoped to reach the Adriatic and sail to Venice. ‘The climb to Moon Mountain is spectacular,’ Hoffstetter wrote. ‘The column wound slowly up to the summit in gigantic spirals, like a long and beautiful snake. Garibaldi rode at their head, beside his heroic wife, followed by his chief officers, recognisable for their white cloaks ruffled by the cool breeze of the mountains.’ To avoid the motorbikes that now use this road as a racetrack, we followed narrow paths up the slopes and looked down on the road’s serpentine curves, with all of Tuscany visible to the west. At the high pass the inevitable memorial stone awaits. ‘These communities still hear the echo of their irresistible yearning,’ the inscription declares. The path our app proposed petered out after half a mile or so and we had to turn back in gathering cloud and got caught in a thunderstorm. The ground dissolved in a torrent of mud. Hoffstetter and Ruggeri recall similar incidents and their effects on morale.

Eighteen miles from where we slept that night, at Sant’Angelo in Vado, an advance party of Garibaldi’s cavalry reported that yet another Austrian army was moving towards them, this time from the Adriatic. The road to the coast was closed. General Stadion was at their heels. Garibaldi once again had the cannon pulled up tortuous mule tracks and headed north. But discipline was failing. The men assigned to security hadn’t sealed off Sant’Angelo’s western gate and a band of Hussars rode in, cutting down 18 men.

The pace quickens now and we struggled to keep up. For miles Garibaldi followed a dry riverbed to escape detection. We tried the same, but gave up after sinking in mud and being tormented by flies. A woman told Belluzzi of a soldier who sat down on the slope outside her village, unwound the rags on his feet, contemplated the bleeding skin, put his pistol in his mouth and pulled the trigger. The men were exhausted, but went into ecstasies north of Macerata Feltria when they glimpsed the Adriatic thousands of feet below and twenty miles to the east. ‘Like proud swans in gilded sunshine,’ Hoffstetter wrote, ‘ships ploughed a mirror-smooth sea.’ Garibaldi shared his last cigar with his officers. He had decided there was no way he could get his men through the Austrian lines to the sea, but he hoped to make it to the neutral state of San Marino, thus saving them from mass execution.

To reach San Marino, first you plunge into a deep valley and ford a stream, then you climb Mount Titan, where the towers and palazzi perch a thousand feet above. The undercarriage of the cannon broke. Losing time trying to fix it, the men suddenly realised that the Austrians in their smart white uniforms were upon them. Garibaldi wasn’t with them. He had gone ahead to strike a deal with San Marino’s governor. For a few minutes it looked as if this would be the end. The cannon was captured. But Anita and the other officers stood firm. She had her whip out and cracked it around the fleeing men. Some kind of order was re-established and the Austrians beaten off. Yet when at last the men filed in through the San Francesco gate, Garibaldi released them from their oath of allegiance. They were to hand in their arms and in return San Marino would negotiate their safe passage home. ‘But remember,’ he said, ‘Italy must not remain in servitude and shame.’

I dislike San Marino. We took a day off here (Garibaldi was leading feverish negotiations from a small café near the town gate). The most visible activity was the sale of duty-free perfumes, liquors, designer goods and above all weapons. Men sat in elegant bars drinking spritz, their new semi-automatics in cardboard boxes beside them.

The Austrians made promises, then backtracked. Garibaldi saw which way the wind was blowing, gathered 250 of the faithful, and at midnight a guide took them down a riverbed between the enemy lines. There was no question of our keeping up with their speed now: they slept only two hours in the next 36. Exhausted, we checked into an agriturismo near the quaint town of Longiano; here, on a terrace looking towards the winking lights of the coastal resorts, we ate spaghetti alla chitarra con funghi e tartufo grattugiato. Anita, now seriously ill, ate a watermelon, slicing it open with her dagger.

At last the final dash to the coast. The hills flattening to plain, the midnight arrival at the port of Cesenatico, where they disarmed the small Austrian garrison. Commandeering fishing boats, they struggled for hours to get them out of the narrow port in a heavy sea. The beach now contains row after row of garish sunshades, old men reading the Gazzetta dello Sport and hordes of screaming children. We felt a sense of anti-climax. Garibaldi had eluded us too. When the men he left behind in San Marino woke up and found their leader gone, they were distraught; they wanted to set out after him; they could not imagine life without the sense of purpose he gave them.

The Austrian navy intercepted the fishing boats off the Po delta, fifty miles from Venice. Most were captured. Garibaldi beached his boat and carried Anita across the dunes. He had just one close friend beside him, lame, wounded and slow. Others who made it to land were rounded up and shot. After days in the marshes, where they were assisted by local patriots, Anita died. But to the chagrin of the Austrians, Garibaldi escaped, recrossing Italy incognito to reach the Tuscan coast and, eventually, America.

Half-heartedly we took train and bus to Porto Garibaldi, near where he landed. It’s a seedy, rundown resort. We walked ten miles to the farmhouse where Anita died, saw the narrow bed where he wept over her, the place where they laid her in a shallow grave. But we never felt as close to our heroes as we had when walking across Italy’s endless hills. Many of the men Garibaldi left in San Marino rejoined him in 1860 for the campaign that swept away the old regime and brought about Italian nationhood far sooner than anyone expected. When he conquered Naples, Garibaldi arrived in the city by train.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.