Letters

Vol. 42 No. 12 · 18 June 2020

Translating Camus

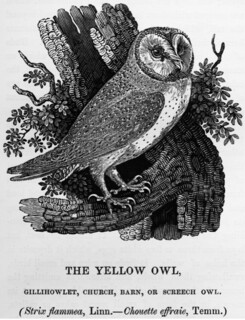

Neil Foxlee reproaches Jacqueline Rose for turning Camus’s ‘hibou rouge’ into a ‘yellow owl’ in her reading of La Peste (Letters, 21 May). But this is Stuart Gilbert’s translation, published in 1948, not Rose’s. In the novel, Tarrou refers to the figure in the dock as an owl four times, as ‘hibou’, ‘hibou roux’, ‘hibou’ and again ‘hibou roux’. Gilbert translates the first, not the second, as ‘yellow owl’. Foxlee misremembers ‘hibou roux’ – roux meaning ‘russet’, ‘ginger’ or ‘redhead’ – as ‘hibou rouge’, and there is such a creature: the red owl, or Soumagne’s owl, named for the French honorary consul in Madagascar who sent a specimen to Paris in the 1870s. But is Gilbert’s ‘yellow owl’ as inexplicable as Foxlee thinks it is? The man in the dock is ‘un hibou effarouché par une lumière trop vive’; in Gilbert, ‘a yellow owl scared blind by too much light’. ‘Effarouché’ may have led Gilbert by association to the yellow owl, one of many English names for what’s sometimes known in French as the ‘chouette effraie’. In the 1972 edition of Le Petit Robert, ‘effaroucher’ is glossed as ‘effrayer’ (to scare, or frighten).

Is there a flickering allusion in ‘hibou roux’ to Soumagne’s owl? If Gilbert knew of the bird’s existence, he might have reckoned a) that any attempt to render it in English should be used for Tarrou’s first reference to an owl to avoid a surprise in the second and fourth; but b) that this bird was unknown in the northern hemisphere and the British colonies. Was there a comparable species that English readers would have recognised? The ‘yellow owl’ is the subject of a wood engraving by Thomas Bewick in Vol. 1 of A History of British Birds (1797). Bewick’s illustration also carries the subheading ‘chouette effraie’.

Jeremy Harding

Saint-Michel-de-Rivière, France

The Bournemouth Set

In his excellent essay about Robert Louis Stevenson and his friends, Andrew O’Hagan misconstrues a quotation from my book on Alice James (LRB, 21 May). O’Hagan writes of her brother Henry:

Twice a day he would walk the short distance to her rooms to be with her for twenty minutes. She did not enjoy his visits. She required them, and agitated for more, but felt he belittled her, as her doctors did. ‘It requires the strength of a horse,’ she wrote, ‘to survive the fatigue of waiting hour after hour for the great man and then the fierce struggle to recover one’s self-respect.’ Her brother in turn had no great wish to live close to her, finding people more tolerable in recollection, or in art.

Alice, in this letter to their brother William, was referring not to Henry but to the doctors (each a ‘great man’) who had failed all her life to solve her mysterious medical problems. The sentence preceding the one O’Hagan quotes is: ‘It may seem supine to you that I don’t descend into the medical arena, but I must confess my spirit quails before any more gladiatorial encounters. It requires the strength of a horse …’ She adored Henry, enjoyed his visits immensely, did not feel he belittled her, and, so far as I know, never referred to him sardonically as ‘the great man’.

Jean Strouse

New York

Andrew O’Hagan writes: I am a great admirer of Jean Strouse’s writing on Alice James, and there is no doubt that Alice was speaking about her doctors in the remarks quoted. However, it seems to me that her remarks about those ‘great men’ carry an inference about great men generally, not excluding those in her own family. That notion, to my mind, is supported by Leon Edel’s view that Henry kept his visits short because she was ‘easily fatigued’. By contrast, Edel immediately says, ‘he spent hours in happy talk with the euphoric Stevenson.’ It is probably wrong of me to draw my own conclusions about Alice’s fatigues, especially when she found such conclusions so fatiguing.

Modelling the Epidemic

In his belief that the elderly and vulnerable should take it on the chin for the sake of the nation’s youth, Roland Salmon calls in evidence a study by the University of East Anglia that compares the UK with other European countries in their attempts to contain Covid-19 (Letters, 4 June). He says the study suggests ‘that general social distancing (lockdown) has had little effect’. But a careful reading of the study suggests nothing so clear cut.

This non-peer-reviewed paper, ‘Impact of Non-Pharmaceutical Interventions against Covid-19 in Europe: A Quasi-Experimental Study’, examined the effect on disease transmission of restricting mass gatherings, the initial closure of some businesses, the closure of non-essential businesses, the closure of schools and colleges, and stay at home orders. It also assessed the use of masks. Its main general finding is that ‘the imposition of non-pharmaceutical control measures has been effective in controlling epidemics’ across Europe, but the authors could not ‘demonstrate a strong impact from every intervention’.

The most effective interventions in reducing the spread of infection were the closure of educational facilities (though the study could not identify which level of school closure was most beneficial), the banning of mass public and private gatherings of any size, and the early closure of some – not all – commercial businesses. These early closures focused largely on bars and restaurants, but the study found that the blanket closure of all non-essential businesses and the imposition of stay at home orders ‘seem not to have had much if any value’.

The findings on mask-wearing were inconclusive. The authors cite two recent studies, one of which suggested that there was little value in wearing a mask outside a clinical setting, the other that community face mask use could reduce the spread of Covid-19. The fact that two studies looking at the same subject could come to such starkly different conclusions suggests that we should treat these studies with a level of caution. Indeed, the authors of the UEA paper add careful caveats to their work, noting that interventions were implemented in different ways in different countries. The timing of restrictions varied; some interventions, stay at home orders for example, were advisory in some countries and enforced in others; a travel ban was specifically instituted in some cases, but part of a stay at home order in others. ‘Because of this variety,’ the authors remark, ‘the results for the potential of stay at home advisories especially may be underestimated.’

It would seem that the complexity and subtlety of the paper was overridden not least by UEA’s press office, which announced it in a press release with the headline: ‘New study reveals blueprint for getting out of Covid-19 lockdown.’

Russell Davies

London SW20

Look out!

Michael Wood doesn’t miss a trick in writing about Keaton’s reliance on banana peel in three of his films (LRB, 7 May). While Keaton wasn’t alone in using this sight gag, his contemporary Charlie Chaplin took a different view. ‘You show the fat lady approaching,’ he explained in a conversation with Charles MacArthur, ‘then you show the banana peel; then you show the fat lady and the banana peel together; then she steps over the banana peel and disappears down a manhole.’

Jeffrey Susla

Woodstock, Connecticut

The Worst Judges

I suppose it could be that Stephen Sedley had in mind the late Ewen Montagu when writing of the senior representative of ‘the worst judges in the country’, formerly sitting at Middlesex Quarter Sessions and then the Crown Court (LRB, 21 May). Certainly the delinquents of West London were terrorised, if not always deterred, by his ferocious reputation. Nevertheless, if he could be brought to see the defendant as an individual personality, things could be different. Early in my time as a probation officer I was summoned to his room and invited to justify my suggestion that a probation order could be the making of a young offender with a bad record: Montagu listened, made the order and happily all turned out for the best. True, counsel could have a rough time in front of him, particularly defenders faced with the difficult task of making bricks without straw. It was no doubt off-putting (a valuable learning experience?) to face a judge with head in hands, audibly muttering ‘Oh God,’ in the course of your plea in mitigation.

I turned the page of the same issue to be surprised and amused to read in Mike Jay’s piece on Edward James of Magritte’s double representation of the back of Edward James’s head. Oddly enough, I too have a picture, alas not by Magritte, that features the back of James’s head in addition to my own rear view: we’re listening to the Academy of St Martin-in-the-Fields rehearsing in Castletown House, County Kildare, around 1977. James was staying with the Guinness family: my recollection is of his continuing flow of talk, and the difficulty of getting a word in.

Conrad Natzio

Woodbridge, Suffolk

The Corrupt Bargain

Eric Foner writes that, under the 14th Amendment, ‘states that deprive significant numbers of citizens of the right to vote are supposed to lose a portion of their congressional representation and electors. But this penalty has never been enforced’ (LRB, 21 May). That isn’t for want of trying. In 1965 the NAACP Legal Defence Fund took legal action to require the director of the census to compile statistics of deprivation and report the appropriate reduction in representation that the 14th Amendment required. A federal appeals court dismissed the case because in enacting recent civil rights legislation, culminating in the Voting Rights Act, Congress had moved in a massive way to eliminate racial discrimination: if such efforts were successful there would be no injury needing redress. But the court added an unusual limitation: ‘In telling appellants that events have made their complaint unsuitable for judicial disposition at this time, we think it also premature to conclude that Section 2 of the 14th Amendment does not mean what it appears to say.’ With an election coming up, the franchise is under attack. The Voting Rights Act was gutted by the Supreme Court in 2013. As Foner makes clear, the court has also permitted the widespread use of tactics such as purging voter rolls, ID requirements, and gerrymandering. Is it possible that these assaults on the right to vote may bring a long forgotten constitutional provision back to life?

Michael Meltsner

Northeastern University, Boston

As a small note to Eric Foner’s illuminating piece on the US electoral college, it may be worth adding that there is currently a case before the Supreme Court seeking to legalise the status of ‘faithless electors’, on the originalist ground that the Founders intended electors to vote according to their consciences and that the subsequent custom that they remain bound by the outcome of the popular vote in their respective states is therefore unconstitutional. It would be ironic that, should the ‘originalist’ justices, who comprise the court’s conservative majority, concur, they may thereby legitimate the liberal National Popular Vote Interstate Compact’s effort to bring about the functional demise of the electoral college.

Albion Urdank

Los Angeles

What to Do with Flowers

In the late 1990s I met Dolores Vanetti – who, as Joanna Biggs notes, nearly displaced Beauvoir as Sartre’s grande passion – at a party in New York (LRB, 16 April). When I told Vanetti that I was a fan of the French philosopher Alain, she offered to give me several volumes of Alain’s essays that had belonged to Sartre. I enthusiastically accepted, imagining that the volumes might contain marginal comments in Sartre’s hand. On receiving the volumes, I was disappointed to find that not only were they free of Sartrean marginalia, but their paper spines had been thoroughly shredded – by, Vanetti told me, her pet monkey.

Jim Holt

New York

Bitten by a Snake

The title of Nathanial Rudavsky-Brody’s translation of ‘Le Cimetière marin’, cited by Michael Wood, demonstrates the first difficulty encountered in rendering Valéry’s famous poem into English (LRB, 21 May). However euphonious it may be, ‘The Graveyard by the Sea’ – the title chosen by the first translator, Cecil Day-Lewis, whom Rudavsky-Brody follows – is wrong on two counts. First, ‘un cimetière’ is a cemetery, not a graveyard: the former, common in Europe, is not on consecrated ground; the latter, common in England, surrounds a church. Second, the cemetery at Sète, Valéry’s native town near Marseille and the unnamed subject of his poem, is above the sea, not ‘by’ it. For my own verse imitation (published in Long Poem Magazine, Winter 2017), I chose ‘The Headland Cemetery’.

Adam Taylor

Chichester, West Sussex

Michael Wood says that Valéry’s notebooks ‘are still awaiting their printed and annotated form’. My bookshelves beg to differ: for years they have held the two-volume Pléiade edition of 1974. Unlike the 13-volume set from Gallimard that Wood mentions, the Pléiade edition is not arranged chronologically, but by topic. What’s more, it is complete, and at more than 3200 pages, will keep the reader occupied for quite a few hours.

James Cowan

San Francisco

Elgin in China

Rory Scothorne quotes Lord Elgin’s remark, of his time as high commissioner in China, that he ‘never felt so ashamed of myself in my life’ (LRB, 21 May). Scothorne includes the destruction of the Summer Palace in Beijing in a list of things Elgin had to be ashamed of. In fact, he was writing about the forthcoming bombardment of Guangzhou in 1857, which would begin, he grimly noted, on 28 December, the feast day of the Massacre of the Innocents. He expressed no such qualms about the destruction of the Summer Palace in 1860. ‘I do not think in matters of art we have much to learn’ from China, Elgin said, though he was ‘disposed to believe that under this mass of abortions and rubbish there lie some hidden sparks of a divine fire, which the genius of my countrymen may gather and nurse into a flame’. It was typical at that time in the West to believe that China had little to offer the world. In the 18th century, a high value had been set on its civilisation, as anyone who has seen the pagoda in Kew Gardens may appreciate, and Enlightenment figures like Voltaire greatly admired Confucian values. But by the 19th century, China had come to be seen as static and tyrannical, in contrast to the Western countries that were energetically industrialising and reforming their political institutions.

Robert Morton

Tokyo

Consider the Greenland Shark

From the southern hemisphere and the relatively warm winter in Sydney at longitude 33.8798°S, latitude 151.1870°E, I send thanks to Katherine Rundell for her insights into the Greenland shark (LRB, 7 May). I too have just consumed at least ‘one and a half chocolate digestives’ – dark chocolate – to ward off hunger and cold. I have also taken an afternoon walk at a speed of ‘somewhere between 1.7 to 2.2 mph’. I am drifting towards the ‘elderly’ category, though not yet odorous or half-blind. Rundell finds hope in the idea of this marvellous marine Methuselah. It’s true that there must be something wonderful about spending a long life in the ocean depths, not giving a damn about human beings.

Suzanne Rickard

Glebe, New South Wales

The White Bus

Susan Pedersen isn’t exactly right to say that The White Bus, Shelagh Delaney’s collaboration with Lindsay Anderson from 1967, ‘was never commercially released though it can now be found online’ (LRB, 4 June). The 47-minute film was intended to form the middle part of a portmanteau feature called Red, White and Zero, between the short films Red and Blue (by Tony Richardson) and Ride of the Valkyrie, starring Zero Mostel. When the production of Red, White and Zero fell through, The White Bus was given a British theatrical release on its own, according to an editor’s note in Lindsay Anderson’s published diaries. The complete Red, White and Zero wasn’t screened until 1979 (in New York), and in December 2018 was finally commercially released on DVD and Blu-Ray by the British Film Institute in a beautifully restored version. Fans of Delaney, Anderson, buses and indeed Arthur Lowe should seek it out in preference to those online bootlegs.

Marc David Jacobs

Glasgow

Polio

Lydia Hill writes that the Salk polio vaccine could be taken by mouth (Letters, 21 May). In fact the Salk vaccine, which came into use in 1956, was administered by injection. It was the 1961 Sabin vaccine that was given orally, often on a sugar-cube, and, largely for that reason, supplanted the earlier one.

Diane Vaughan

Little Silver, New Jersey

Read anywhere with the London Review of Books app, available now from the App Store for Apple devices, Google Play for Android devices and Amazon for your Kindle Fire.

Sign up to our newsletter

For highlights from the latest issue, our archive and the blog, as well as news, events and exclusive promotions.