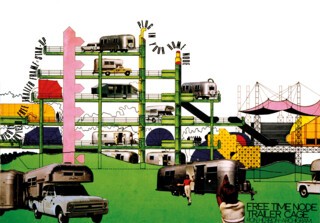

Archigram was an out-of-hours architectural band of six men – Peter Cook, Warren Chalk, Ron Herron, Dennis Crompton, Michael Webb and David Greene – whose day jobs were with big commercial practices and local authorities. They formed in the early 1960s and over the next decade or so produced thousands of designs for ‘cities of the future’ that were highly original, sometimes on the money, sometimes woeful, often funny, reliably coarse. They were artists as much as architects and Archigram seemed at times like a sci-fi serial without a plot; an anthology of wacky improbabilities, such as Ron Herron’s Walking City, in which ‘intelligent’ buildings (they look like a convention of bodybuilder pangolins) move around of their own accord; a spanner in the works of ‘responsible’ architectural discourse, which means timid discourse; a polemical comic that relied on fine draughtsmanship, drawing of the highest calibre, shock-tactics collage and inspired design. Like Ballard, who wrote on a typewriter, Archigram foresaw the future with Luddite tools. The group’s precepts and dicta changed by the hour. It created what were not yet called installations. It was supposed to be fun (though sometimes fun can get wearisome – a student jape by pranksters too old to be students).

In the sixty years since its founding, Archigram has become a self-mythologising, energetically self-celebratory bastion of old-fashioned avant-gardism, as tied to its era as popping out to a Schooner Inn for a half of Red Barrel. The former members have sedulously controlled their image. The hype has worked. A collective dedicated to impermanence and expendability has sold its archive for £1.8 million to M+ Museum in Hong Kong, designed by Herzog & de Meuron, a practice which Cook, the most visible member of Archigram, formerly derided.

There have been countless exhibitions, conferences, retrospectives, retrospectives of retrospectives, catalogues, (un)critical apparatuses, dozens of adulatory books of which Archigram: The Book is merely the most recent respectful documentary. And hardly any buildings. That’s the only quality Archigram shares with more orthodox designers of the City of the Future. Otherwise it abjured the illustrative tradition of, inter alia, late-19th-century imaginaries such as Albert Robida and Warwick Goble who illumined the texts of Verne and Wells. It broke, too, with another tradition: that of integrated rationalism whose extreme manifestation was Le Corbusier’s glum Plan Voisin for the destruction of Paris, a self-advertisement worthy of a base politician. Archigram was a reaction to the purity of the white orthogonal architecture of the 1920s and early 1930s championed by Nikolaus Pevsner, the most conservative of progressives, who described English architecture of the 1950s as ‘not the functionally best solution, nor an economically justifiable solution, nor acceptable in terms of townscape’. Early on, conventionally enough, the practice entered competitions, some for high-vis projects, but more usually for motorway service stations, educational buildings, social housing estates, comprehensive redevelopments (as ‘iconic’ regeneration campaigns were then called). The competition entries gave little indication of what was to come. The more rejections the six received, the more farouche their work became, the more unrealisable. The page or the gallery was as far as their imagined buildings would go. A design, they claimed, was not a stage on the way to glass and brick, but an end in itself.

Perhaps. The group’s rather wobbly aim seems to have been to create a representation of tomorrow that wasn’t escapist, douce and cuddly but much closer to the dense, pitted strata of imperfection to which all cities eventually yield. There is no flight from the gruesome chaos that flawed humans and their flawed programmes create. The germs of decay, of mechanical and electrical shutdown are everywhere implicit in Archigram.

Archigram’s members weren’t hippies. They were of the generation that did National Service, just too young to have fought in the Second World War. David Bailey once said that ‘Swinging London’ was ‘just national servicemen gone demob happy’. They were radical materialists who believed exclusively in what they could see and what their imaginations delivered them. Transcendence was not on the agenda. Bucolic revivalism, communes, cults, weekend mysticism, twenty-minute guitar solos and terrible clothes were not part of their world. Archigram was opposed to such retrospection. Its aesthetic had, after all, been established in the technophilic early 1960s.

The subcultural change that led to the demise of this aesthetic was, according to George Melly, signalled by a ‘secret society’ that congregated at the party for the V&A’s Aubrey Beardsley exhibition in the summer of 1966. The next future would be looking backwards. Archigram’s architectural collages had always included ‘dolly birds’ and ‘get-away people’, ‘the fun set’ and ‘people in a hurry’ and other impatient clichés of their hedonistic era; when the dolly birds went from minidresses to Laura Ashley there was a fundamental disconnect between the collective’s imagined decors and the people inhabiting them. As a graphic force, Archigram’s Rotrings and whiteprint were briefly pushed aside by a combination of acid and airbrush, Mucha and Pogany.

But as an architectural force this practice that resisted the label ‘practice’ and which built virtually nothing was increasingly potent, perhaps for those very reasons. Its ideas were often garbled and incoherent but reliably catchy. Its sightbites were persuasive and covetable. Its rare political prognostications were inaccurate: it brought into the commonplace the idea that mechanisation would bring leisure rather than slavery. Its apothegms were unconvincing, but that hardly mattered. It wasn’t the speech bubbles in Dan Dare that enchanted a generation of future architects but Frank Hampson’s drawings. Like Piranesi and Lequeu, J.C. Loudon and the Ideal Home Book of Bungalow Plans, it threw generous scraps to the less inventive. What Archigram drew, its disciples built – in diluted forms acceptable to planning authorities whose taste was three decades in arrears and to clients scornful of architectural integrity. Among the early debts to Archigram was Levitt Bernstein’s Royal Exchange theatre in Manchester: an ingenious structure which bellowed ‘Design!’ and was met with incomprehension. The Beaubourg, the first major building obviously in thrall to Archigram, was equally unfavourably received. The reaction of the members of Archigram and their collaborator Cedric Price is shown in a film from 1980 in which they turn up in a minibus, apparently gobsmacked – amazed, amused – and increasingly resentful at the sheer effrontery, the diabolical liberty taken by Piano and Rogers. Cook wrote with venomous tact of ‘the believed manifestation of Archigram ideas in several buildings that have been made by [Norman] Foster and his friend Richard Rogers … it raises all those classic issues about origin, innovation and the ownership of ideas.’ Indeed. But then so too do the off-the-peg Victorian-medieval churches that constellate England.

Archigram’s flaw was its timing. Founders seldom prosper. Being too original scares the punters. It’s the second and third waves that succeed – they include Will Alsop, Future Systems, Rem Koolhaas and Coop Himmelb(l)au. And while architecture may be 10 per cent bedsit lucubration, it is 110 per cent a cut-throat business that demands graft, oily diplomacy, baksheesh, clubbable chumminess, anilingual shamelessness. In their day jobs Archigram’s original members worked for Taylor Woodrow, the construction giant that erected several of John Poulson’s designs (there was an architect who got his priorities right: he could grease a palm up to the elbow). They learned nothing from him.

A wrongheaded hierarchy of realities grants primacy to a breezeblock over a painting of a breezeblock, to the sweating dominatrix over Dix’s portrait of her. While Archigram’s members moved, faute de mieux, into academe, their insouciant epigoni made their designs ‘real’, without necessarily knowing the sources they were drawing on. Their inventions and wheezes and jests seeped into the collective architectural and sub-architectural consciousnesses to form a language casually picked up piecemeal.

Archigram’s ghost, a very colourful ghost, is everywhere: in the recycled containers that have perhaps improved conditions in bidonvilles from Dakar to Ho Chi Minh City; in the crazily knotted service pipes that spill from Aachen’s University Hospital; in the 12-storey city of Harwich that looms above the two-up-two-downs then recedes, leaving a view of the Stour’s confluence with the Orwell; in the decorative ‘golden brains’ at the top of Yuri Platonov’s Russian Academy of Sciences in Moscow; in the wine gum-coloured spectacles by which one architect recognises another. And, most satisfyingly, in Archigram’s Kunsthaus Graz, a tentacled blue growth designed by Cook and Colin Fournier. It got built.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.