The Staffordshire Hoard , discovered by the metal detectorist Terry Herbert on 5 July 2009, presents far more of a puzzle to archaeologists and historians than the other famous Anglo-Saxon discovery, at Sutton Hoo. The start of the puzzle is working out what is there. The hoard weighs in at about five kilos of gold and almost two kilos of silver, and some claim you could pack it into a shoebox. The immensely detailed, multi-authored archaeological report from the Society of Antiquaries suggests, more sensibly, a couple of saddlebags. Unlike the Sutton Hoo treasures, which were discovered lying within a chamber within a ship within a barrow, the site of the Staffordshire Hoard had been disturbed by ploughing, so that the contents were scattered over an area more than ten feet square, with a couple of items so much further away that they might not be part of the hoard at all.

One can’t even say how many items it contained. The ‘Abbreviated Catalogue’, which takes up nearly a hundred pages of the report, lists 698 items, almost all of them dismembered, out of 1381 finds. The helmet is listed as four items in the catalogue, including a cast crest and two cheek pieces. But it originally also had a silver band decorated with running or kneeling warriors: this has been reconstructed from more than a hundred fragments, out of a total of 557 fragments of decorated silver sheet – it’s on display at the Birmingham Museum and Art Gallery. George Speake, the author of the entry on the helmet, claims that it was ‘a magnificent prestige item’, more ‘gilded and gleaming’ even than the iconic visored helmet found at Sutton Hoo. Despite the reconstruction, however, it’s not impossible that the fragments come from more than one helmet.

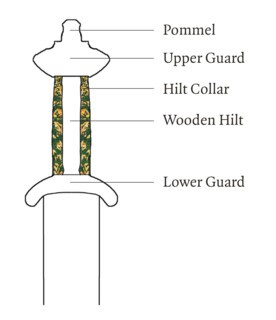

What one can say is, first, that the hoard is unique from the period. Previous discoveries have been grave burials, or single finds, not collections buried with (presumably) the intention of later recovery. Second, the general nature of the hoard is clear. It is strongly weapon-related, but without weapons. There are no coins, no brooches, no items of women’s jewellery, not even a single knife or sword blade. Some 80 per cent of the objects are fittings from weapons, mostly sword-hilt parts. An Anglo-Saxon sword typically had a wooden hilt fitted over the iron tang on the blade, but to this were added an upper and a lower guard, each secured by two hilt plates and a hilt collar, fixed by bosses, with a pommel on top. All these appear in the hoard in large numbers.

The authors point out that not long ago only one Anglo-Saxon sword pommel was known (from Sutton Hoo); the number found in the hoard currently stands at a minimum of 74. It represents not the equipment of one man, or one king, as at Sutton Hoo, but the relics of a small army, ‘in excess of a hundred aristocrats’ – sword-wielders not rank and file spear-carriers. All this looks pretty ominous, as do most things about the hoard. It’s plainly the result of deliberate dismantling. Someone collected several man-loads of weapons and took them to pieces. Many items show signs of wear, indicating that they were in use for a long time, and may have been family heirlooms, but there are also tong marks, indicating that pommels were wrenched off forcibly. Clear incisions on some of the pieces suggest that there was no great time gap between the disassembly and the burial, and it’s unlikely that there was much intention to re-use the material directly.

In fact, if one glances through the pages of illustrations in the report, the impression they give is of scrap metal: plates and wire, bent, twisted, sometimes folded, ‘destined for the melting pot … to be refashioned into new prestige objects’ – but not quite yet. Some of the garnet jewellery was loose, but the stones hadn’t been removed, as they would have been before throwing the gold settings into the crucible, and the inlays were still present. So how did this strangely homogeneous collection come about? An obvious answer is provided by the Anglo-Saxon terms wæl-stow, here-geatu, beah-gyfa. Wæl-stow means ‘place of the slain’ – killing ground, battlefield. The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle frequently reports on who, at the end of the day, ‘had control of the battlefield’, as in its 871 entry on a string of battles between the West Saxons and the invading Vikings. The West Saxon chronicler patriotically claims many Viking casualties, and twice says that Alfred and his brother Æthered were winning longe on dæg, ‘for much of the day’, but then concludes, honestly if lugubriously, that þa Deniscan ahton wælstowe gewald, ‘the Danes had control of the battlefield.’

Being in possession of the battlefield at the end of the day brought obvious benefits. Since there was no convention about taking prisoners, even for ransom, you could both tend your own wounded and finish off any of the other side who had been left behind. Possibly even more important for the hard-headed war leader was the fact that possession of the field also allowed one to recover the weapons of fallen comrades while gaining a big haul of the opposition’s. If all the swords, spears, helmets, shields and mail shirts were gathered up, some sturdy churls and aspiring warriors could surely be found and kitted out, restoring the army to fighting strength. But there’s a complication here, because it isn’t always clear who got the loot that was recovered. In later times the word ‘heriot’ meant a tax, a kind of death duty, but the idea behind it was that once upon a time a lord issued ‘war gear’ (here-geatu) to his retainers, and claimed it back on their death or retirement. So some of the weapons a commander salvaged from his own side might go to the king or lord, who might equally have a claim on the war gear of the defeated.

Robbing the dead could be profitable in other ways, as an incident in Beowulf illustrates. When Beowulf arrives at Denmark on his mission to destroy the monster Grendel, he is challenged by a Danish coastguard, who remarks on Beowulf’s formidable appearance: ‘That is no hall-man, wæpnum geweorþad [made worthy by weapons].’ This tells us, first, that people in the heroic world were aware of men who looked like warriors and weren’t – they only had the gear – but also, more relevantly for the Staffordshire Hoard, that the worth or status of a warrior could nevertheless be estimated most readily by the worth or value of his equipment. The finale of the Society of Antiquaries’ report, a reconstructed sword hilt glittering with gold and garnet designs, shows this at work: it makes a gold Rolex look understated.

Warriors carried their wealth with them, and lost it in defeat. The most valuable object mentioned in Beowulf is the great torque, or neck ring, given to the hero by the Danish queen, which he seems to have passed on to his uncle Hygelac, king of the Geats. But the poet also notes its loss: it was stripped from the king after his defeat in battle by the Franks, when he ‘fell beneath his shield’ and ‘worse warriors robbed the dead.’ A sensible warrior who stripped such an item from a corpse would never keep it for himself but would make a public gift of it to his own lord or king, expecting, of course, some kind of reward. And a sensible lord would make arrangements for a dividend to those of his own men who deserved it. Such a figure appears in poetry as a beah-gyfa, a ‘ring-giver’, the one who distributes wealth and recognises worth.

Is that what lies behind the hoard? Does it represent a stage in the sharing out of loot? If so, one wonders whether it might have made more sense to hand out prestige weapons in a complete state, instead of taking them to bits. The report suggests that the deliberate dismantling may have been ‘ideologically driven’, the destruction of symbols of identity and authority. A famous sword, perhaps an heirloom with its own name, might prove a future focus for rebellion or – as mentioned in Beowulf – a call for vengeance: best make it unrecognisable. But then there is the even more puzzling question of how and why a whole armoury came to be buried. The depositing of treasure at Sutton Hoo was clearly a public and very visible affair. It must have taken a large work gang to drag the ship up from the River Deben to the barrow where it was buried, and all the barrows on the site have been on full view from that day to this. The Staffordshire Hoard, however, seems to have been buried secretly, in an unmarked field, fairly close to major travel routes but not visible from them, and with nothing on the surface. Hoards like that are usually taken to be a bad sign. They mean that valuables have had to be hidden for safety, and of course it’s an even worse sign that no one ever came back to reclaim them.

In attempting to understand how this situation came about, it’s worth noting two important features of the hoard, one geographical and one historical. The hoard was buried in what was then the Anglo-Saxon kingdom of Mercia, about ten miles west of Tamworth, which would eventually be the major Mercian royal centre, and only five from Lichfield, where later Mercian kings hoped to establish their own archbishopric. The area was something of an intermediate zone between two different groups of Anglo-Saxon settlers, the Pencersæte along the River Penk and the Tomsæte along the Tame: one scholar has said the site is ‘not so much marginal as liminal’, intermediary between Angles and Britons, between different groups of Angles, between northern and southern Mercia. Its closeness to the intersection between the old Roman roads of Watling Street, running east to west, and Ryknild Street, running north to south, might also put it in an area convenient for neutral assemblies. Where better to share out the loot from a successful campaign?

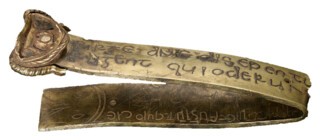

As for the historical issue of date, one clue is the presence of eight definitely Christian items, including the largest single object in the hoard (though still quite a small one): a gold processional cross, folded up as if to be put in a bag or box, but originally about a foot tall. In addition there are several small crosses, something that might be part of an ecclesiastical headdress and what appears to be the base of an altar cross. Most revealing, though, is an inscribed strip, perhaps once also fixed to the arm of a cross, with a quotation from Numbers 10:35, which in the King James Version begins: ‘Rise up, Lord, and let thine enemies be scattered.’

The interesting thing about the inscription is that it’s so badly done. The quotation has been inscribed twice, the first attempt presumably having been rejected as substandard. Yet even the second betrays a lack of familiarity not just with the Latin language but with its alphabet. The phrase inimici tui is written first as inimictiui, and then corrected. The Bible reading dissipentur comes out once as disepintur and once as disepentur, suggesting confusion between the Latin verbs dissipare, ‘to scatter’, and dissepire, ‘to tear apart’. ‘May your enemies be scattered, may your enemies be torn apart.’ Either would be a perfect choice for a cross used as a battle standard – Oliver Cromwell is said to have used the same quote at the Battle of Dunbar – but only one can have been intended, and whichever it was the word came out wrong. There are several other errors or inconsistencies.

Just the same, the presence of Christian items suggests the hoard postdates the arrival of Christian missionaries to the Anglo-Saxons. They came in a kind of pincer movement, from north and south: St Augustine began his mission in Kent in 603, while Christianity in the north began with the conversion of King Edwin of Northumbria twenty years later. Mercia, however, resisted for another generation, and the combination of Latin, literacy and Christianity was not far advanced by the time of the hoard, as the inscription attests (it also indicates that these items weren’t looted from the long-Christian kingdoms of Wales). Such a conclusion fits quite well with the dates implied by the nature and style of the objects retrieved, and by the quality of the gold, which in north-west Europe became steadily worse during the seventh century as imports from the south dried up. All these considerations point to a date for the materials in the hoard between 590 and 650, with a preference for the last quarter-century of that period.

What signs of trouble were there in Mercia at that time? The short answer is: almost too many to choose from. It doesn’t help that the two main accounts of their own history by Anglo-Saxons come from the Venerable Bede, who was a Northumbrian, and The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, compiled in Wessex. But the main suspect here, as Barbara Yorke points out in her contribution to the report, is King Penda, whose story – Mercia being in the middle of England – is one of continued conflict against the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms of Northumbria to the north, East Anglia to the east, Wessex to the south and the Welsh kingdoms to the west. Penda, who ruled from roughly 626 to 655, certainly had several opportunities to accumulate battlefield wealth. His first major campaign was against the saintly King Edwin of Northumbria, whom he killed at Hatfield in 633. In 642 he killed Edwin’s equally saintly successor, King Oswald, perhaps at Oswestry. In 645 he drove King Cenwalh out of Wessex and in 654 he killed King Anna of East Anglia. He also raided deeply into Northumbria, reaching as far as Bamburgh some time before 651 and taking a heavy toll from the Northumbrian king, Oswiu, perhaps as far north as Edinburgh, in 655. Oswiu finally put a stop to Penda’s charge, finishing him off at the River Winwæd, possibly near Pontefract, later that year.

Also to the point is the fact that Penda was an inveterate pagan, who would presumably see nothing sacrilegious about looting Christian churches and treating crosses as booty. This could account for what looks like deliberate damage done to one item in the collection, a cross-pendant with one arm broken off and the other bent. Bede, however, concedes that while the Mercians were ‘idol-worshippers ignorant of the name of Christ’, Penda didn’t forbid Christian preaching in Mercia and tolerated Christians as long as their conversion was sincere. His intermediary position between Christian and pagan is similar to that of King Rædwald of East Anglia, who is almost certainly the man commemorated at Sutton Hoo: a thoroughly pagan ship and barrow interment which even so contained a pair of baptismal spoons, marked ‘Saul’ and ‘Paul’ to indicate conversion.

The hoard, then, could easily have been part of Penda’s winnings, looted indiscriminately from his Christian neighbours, whether British or Anglo-Saxon. If we take the speculation further, it could well have been hidden after his death, in the disturbed period when Oswiu took control of northern Mercia and established Penda’s son Peada as king of southern Mercia, only for Peada to be murdered and replaced after a three-year interregnum by his brother Wulfhere, who had been kept in hiding by Mercian loyalists. Alternatively – if we consider the fact that, whenever it was accumulated, the hoard may have been buried any time after the date indicated by the objects themselves – we could look for explanation to the Mercian civil war in 716 between rival descendants of Penda. Yorke suggests that the hoard could have been assembled and vandalised by the winning side in an attempt ‘to obliterate traces of their rivals’. But as she also says, putting it mildly, there was more than one ‘uncertain period in Mercian politics’.

The possibility remains that the hoard is the result of straightforward theft, done simply for profit. Not far from the site is the village of Hammerwich, which as its name suggests may have been the location of the Mercian kings’ smithies. If the material was all waiting to be melted down and reworked, a thief (or a smith) might simply have made off with it, burying it quickly before he was traced. Many things might have prevented his return: being caught, for instance, and promptly hanged. But this is a consideration for a future Rosemary Sutcliff or Bernard Cornwell.

Even if you give up the mysteries as unsolvable, there is still much to be said about the artistry of the hoard, as revealed in the many illustrations in the archaeological report. It’s hard to pick out individual items from the mass of information when every scrap and fragment is listed, considered and weighed. Some of the material was less dauntingly presented in a booklet put out in 2014 by the British Museum, which gave a short account of the hoard and included a number of illustrations. The most striking appears at the start: it shows what a find looks like at the moment it’s uncovered from the earth. It must have been a heart-stopping moment for Terry Herbert: all those days spent tramping through fields with a metal detector were worth it after all.

But there’s more insight to be gained from another little book, Chris Fern and George Speake’s Beasts, Birds and Gods, also published in 2014, which selects a few telling samples for study and shows us how to read them. Zoomorphic art is prominent in the hoard – animal shapes, characteristically stylised and intertwined. One sword pommel, in gold and garnets, displays stallions fighting; on another, in silver, a bearded head stares out between a pair of unidentifiable beasts. The authors suggest old pagan significance in the boars, serpents, bears, eagles and strange chimeras, and in the mounted or marching warriors, with parallels in the pagan Scandinavian world. Even the processional cross, though in the Byzantine tradition of the crux gemmata (it’s now missing its six jewels, probably red garnets), has a decoration of interlaced animals on staff and crossbeam. These things come from a place where Roman and Scandanavian traditions, Christian and pagan, civilised and barbarian, all mixed and cohabited. The Staffordshire Hoard reminds us how much remains in the ground.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.