‘The musicians of my generation, and I myself, owe the most to Debussy,’ Stravinsky said, but he would also say that, much as he admired Jeux, he found some of the music in it ‘trop Lalique’, a remark of a certain cattiness, calculated to put Debussy’s protean and elusive masterpiece back in its box, at a moment (it was 1959) when, perhaps not altogether desirably for the composer of Le Sacre du printemps, Jeux was belatedly becoming the poster piece of the avant-garde, the work everyone at Darmstadt would be talking about.

Debussy died in 1918. A century later, his music may at first appear more decorative than radical. The shock of the new is hard to feel at a distance, but as Stephen Walsh observes, we expect the music of the modernist generation, of whom Debussy was the first, to be difficult, abstruse, even rebarbative. The works of Schoenberg, Webern, Stravinsky and Bartók continue to present us with a residue of toughness. By comparison, the musical culture comfortably digested Debussy’s innovations, and it’s easy to overlook the departure they represented.

His strangest, most discomfiting piece is the second movement of En blanc et noir, a three-movement work for two pianos from 1915. In July that year, Debussy left Paris for the seaside, taking a house in Pourville near Dieppe, where he and his family (his wife, Emma, and their ten-year-old daughter, Claude-Emma, nicknamed Chouchou) spent the next three months. The house – Mon Coin – had a garden and a view of the sea, and Debussy seemed happy there, writing of it without his customary grumpiness. He had reason enough to be low-spirited: he had rectal cancer, and each day brought grim news from the front; yet, despite it all, he managed to compose. The completion of En blanc et noir broke a long creative drought and ushered in the last flowering of his genius, before illness made serious work impossible.

The first movement of En blanc et noir bursts into the world with a cascade of C major exuberance, which even Debussy was surprised by. He dedicated the third movement to Stravinsky and it too is alive with scherzando energy, so that the second movement seems like a gloomy declivity between two sunny outcrops. It’s prefaced by lines from François Villon’s ‘Ballade contre les ennemis de la France’ and is evidently intended as a cry of protest against the anguish and horror of war – perhaps too evidently. Where the outer movements of En blanc et noir communicate an exhilarating effortlessness, the energy of the middle movement seems blocked, as if the music were inhibited by its own high aims. A grim procession of broken and disconnected musical figures trudges past: muffled drum beats, bugle calls, forlorn scraps of melody, brave gestures at choral solemnity. The piece is marked ‘Lent. Sombre,’ and its mood is one of impotent anger: the music tries to weep, but no tears come.

At the centre of this strange movement there is a militaristic outburst in which harshly harmonised fragments of ‘Ein feste Burg ist unser Gott’ are hammered out. The impression here of a message too much striven for contributes to an overall feeling that Debussy is out of his skin in this piece. The rawness of the material gives the music a desperate poignancy, but it is an effect achieved outside art and it reminds us that Debussy’s expressive range does not naturally encompass pain.

For Debussy, the adversary had always been Germany. He was eight in 1870, old enough to understand the depth of national humiliation in the war against Prussia. The study of music quickly brought him up against the Austro-German hegemon, and the fashioning of a distinct identity for French music would be a vital preoccupation for him as a composer. Without the war of 1870 and its consequence in the Paris Commune, he might never have become a musician at all.

Not much is known of his early years. His father was poor and without a steady occupation. The family (Debussy was the eldest of five children) moved frequently. Unlike his direct contemporaries, Mahler (two years older) and Strauss (two years younger), Debussy had none of the advantages of infant immersion in musical culture. At three, Mahler was picking out tunes on his concertina; Strauss started piano lessons at four. What Debussy was doing at this age, we can only guess – playing in the dirt of a Paris back street, perhaps.

There is no record of Debussy attending school, and his father had him down for a life as a sailor. His musical talent was discovered by chance. In 1871, his father was arrested for participating in the Paris Commune, and in jail became friends with a musician, Charles de Sivry, whose mother – Antoinette-Flore Mauté – was a talented pianist and teacher who claimed to have been a pupil of Chopin’s (as it happened, she was also Verlaine’s mother-in-law). It was Madame Mauté who recognised Debussy’s exceptional musicality. She gave him piano lessons and a year later, aged ten, he was admitted to the Paris Conservatoire, the youngest candidate then to be offered a place.

Arriving at music late, and from the other side of the tracks, Debussy had the benefit of an unprejudiced perspective on the things he was taught. He was a gifted pianist. Within two years of entering the Conservatoire he gave a performance of Chopin’s F minor piano concerto and it was assumed he would have a career as a virtuoso. Though he turned to composition, the piano would remain at the heart of his life as a musician. There are stories of him as a student, sitting at the piano and provoking his teachers with sequences of unconventional chords. As a composer, he always liked to improvise, though he knew the possible pitfalls of this way of making music. He had an incomparable ear, and one can imagine him at the keyboard trying things out, feeling his way into new and unfamiliar areas, listening intently to the sounds his fingers were uncovering, testing them for their interest, implication and beauty.

In the musical language that Debussy was taught and that he would, in important respects, reject – the language of classical tonality – the distinction between dissonance and consonance is axiomatic. Individual dissonances must be resolved, areas of harmonic instability restored to equilibrium. Each degree of the diatonic scale is assigned a place in a hierarchy of relations with the tonic. The strongest degree is the fifth – the dominant – and dominant-tonic relations are at the centre of every musical structure. The discourse is highly directional: phrases and melodic lines are thought of as rising to a point of climax and then subsiding, modulation is a journey away from the home key and back again, structures unfold like arguments or stories. Many of the metaphors used to describe tonality – tension and resolution, disorder and equilibrium – are metaphors of feeling.

In the half-century before Debussy was born, composers had progressively disrupted the stability of the tonal system, exploring its potential to represent more extreme states of mind. The late works of Chopin, for example, express an agitation that Liszt thought verged on the pathological. The withholding of harmonic resolution in Wagner’s mature style – most famously exploited in Tristan und Isolde – threatened to take music into the realm of hysteria. Where could it go next?

One answer was simply to push on further, to ratchet up the harmonic and emotional tension to the very edge of psychosis, as Schoenberg was to do in Verklaerte Nacht and Strauss in Salome and Elektra. These are works in which a system is at breaking point. Reaching the border, Schoenberg went over, Strauss turned back. After Elektra, the guardians of ideological soundness never forgave Strauss. He was labelled a cynic and a coward for his next opera, Der Rosenkavalier. Elektra had almost been split apart by its stylistic contradictions: the sense of compositional stress in the more daring music of that opera adds to its derangement, but the queasy eruption of music from the Vienna woods into the charnel house of Agamemnon’s palace clearly pointed to the work’s true centre of gravity. This wasn’t something Strauss could possibly repeat and, for all the flak he received, one can only think he was wise to listen to his nature.

Debussy moved in the opposite direction, developing a musical language that relaxed harmonic and emotional tension rather than raising it. He was motivated by a need for a medium that would allow him to represent non-directional states, whether of energy – subtle drift (clouds, mist), great force (wind, waves), unified fields of intricate and random motion (reflections on water, fireworks) – or of feeling (sentiment and sensation). He rejected narrative and dialectical structures in favour of a music of apposition, placing one thing next to another – harmonies, motifs, even structural units. His harmonic language is usually spoken of as ‘non-functional’, a term that describes a way of writing music which uncoupled harmonies from their place in the tonal hierarchy and reduced the force fields between them. Perhaps a better description would be ‘less functional’: for all its rejection of routine procedure, Debussy’s music is awash with tonality and achieves its expressiveness as much from changing the emphasis of the existing idiom as from introducing elements entirely foreign to it.

His music is a naturally evolved inflection of the musical language he inherited – a continuation rather than a rupture. The whole tone scale and the harmonies implicit in it (musical elements that Debussy particularly liked) were not, in themselves, outlandish to the ears of his contemporaries. It was just that Debussy used them outside the contexts that obscured their perceived strangeness. Schoenberg, ruminating on the ‘emancipation of the dissonance’, acknowledged that Debussy had already unlocked the cage and thrown away the key. For all his valiant and ingenious attempts to argue for atonality as a continuation of the tonal system, Schoenberg had to admit that listeners simply didn’t feel this – his hope that one day people would whistle his tunes turned out to be forlorn. Unlike the younger composer, Debussy did not adhere to an ideology which held that all chords are equivalent: it was the individual character of complex harmonies that interested him; he praised César Franck as a composer ‘for whom sounds in and of themselves have a precise meaning’. (The quotation is included in François Lesure’s biography, an invaluable scholarly resource, now translated into English for the first time.)

Debussy was exceptionally responsive to the music of other composers, a permeability which helps explain our sense of the embeddedness of his work within the musical tradition. He sought his models for the most part outside the Austro-German mainstream: in the music of the great Renaissance polyphonists, Palestrina, Victoria and Lassus; in Couperin and Rameau; in Chopin (his great love) and Mussorgsky; and in non-Western music, especially the music of the Far East. Of the Germans, Schumann was particularly important to him. And then there was Wagner, whose influence threatened to overwhelm him. As a young man, he found ways to dismiss the Ring, but Tristan and Parsifal exerted a force that could not be ignored and he had no choice but to make terms with them. The story of that accommodation was the story of his career as a composer, as Robin Holloway grippingly demonstrated in his early book Debussy and Wagner. Holloway’s explication of Jeux, Debussy’s 17-minute ballet, as a molecular refashioning of Wagner’s four-hour opera, is a tour de force of applied musical analysis. Holloway sees Jeux as the work in which Debussy finally laid Wagner’s ghost to rest – but it had taken him the best part of three decades.

It wasn’t until he was in his early thirties, a decade after he graduated from the Conservatoire, that Debussy found a voice with which to begin to answer Wagner, in two works – Prélude à l’après-midi d’un faune and Pelléas et Mélisande – which would eventually establish his reputation as a major composer. He began work on Pelléas in 1893, completing the first version of it two years later, and wrote Prélude à l’après-midi d’un faune between 1892 and 1894. The sovereign assurance of his genius as a composer is announced in the prelude’s first ten bars, a gesture of irresistible beauty that turns the musical conversation away from Wagner in a brilliant and irreverent misprision of the master’s most famous chord progression. At a stroke (or should one say, with a little gentle stroking), the prelude blasphemed against the necessity and the high seriousness of the German musical tradition. It showed that there could be other ways of doing things: different scales, different arrangements of common chords, perfectly delightful arrangements of not so common chords, new kinds of structure. And it was unashamedly secular. Since the beginning of the 19th century, the claims made for tonal music had been escalating, and a powerful strand of essentialism had developed, whereby classical tonality was accorded the unassailable status of a system based in nature. This way of thinking was to reach its most extreme formulation in the 1920s in the writings of Heinrich Schenker. In his rather alarmingly titled periodical Der Tonwille, subtitled ‘Pamphlets in Witness of the Immutable Laws of Music’, Schenker would speak of ‘truth in the realm of tones’ and the ‘truth of the triad’. He was an unreconstructed nationalist, but, on the left, Adorno would elevate the tradition of German music in comparable ways. (Schoenberg, irritated by the way Adorno championed his music, once sardonically asked a friend ‘Was macht die Musik?’, answering the question himself: ‘Sie philosophiert’.) For Adorno, the ideal way to listen to music was silently, in the head, and he criticised Debussy for his ‘fetishising of the material’ – i.e. sound.

Although he wrote more music criticism than most composers, Debussy was not a theorist. He sought to compose music that was expressive and beautiful, and he grounded it in the quality of his ear and in his musical intuition. It wasn’t only that he was restlessly bored with formulaic solutions to composition, but that he felt music had become too noisy and too rhetorical, and that in its high claims to various kinds of content – religious, cod-religious (Wagner), philosophical, psychological, sociopolitical, whatever – music had forgotten its origin in sound. The racket and bombast of much late 19th-century orchestral and operatic music distressed him. It was as if he couldn’t hear himself think, or rather, as if he couldn’t hear himself hear. Debussy’s music is capable of wonderful gaiety, exuberance, jubilation, ecstasy; yet, given his preoccupation with sound, it was inevitable that an unusual proportion of his work – compared to that of other composers of his time – would sit at the quieter end of the dynamic spectrum, as Stephen Walsh points out, and it’s one of the reasons it is difficult to perform well: the modern concert piano is incapable of the differentiations of pianissimo that Debussy asks for, and the subtle discriminations of his orchestral works, such as La Mer and Jeux, pose big challenges for even the best players (and for conductors: Boulez, the finest interpreter of Debussy’s orchestral works, described titrating the tone of Jeux as a matter of hair’s breadth musical judgment).

Given Debussy’s mission to bring music back to its origins in sound, it seems on the face of it paradoxical that he should have attached words to so many of his works. It led critics to label him an ‘Impressionist’, which vexed him, and the association between his music and turn of the century French painting has become a cliché of our thinking about him. Walsh, who has attempted the ambitious task of counterpointing a retelling of Debussy’s life with accounts of all of his important pieces of music, clearly knows that the connection between music and visual art is spurious (he says as much on a number of occasions), but – perhaps at the behest of his publishers – he has called his book Claude Debussy: A Painter in Sound. The analogy between music and painting is unhelpful: they are two art forms with little in common, since music’s main expressive modality is to enact movement, the one thing painting cannot do. It’s significant that Debussy placed the descriptions of his piano preludes at the end of each piece, rather than at the head, which suggests that we are to take the titles and descriptions he attached to his music more in the manner of similes in poetry than as directions to think of it as depicting things: reflections in water, goldfish, fireworks, least of all girls with flaxen hair or sunken cathedrals.

The practical function of Debussy’s titles was to provide distinct identities and simple frames of reference for pieces of music whose idiom contemporary listeners might have found hard to grasp – a way of helping them get their bearings. Their more polemical purpose was to direct us to think of music not as ‘deep’ but as rooted in the physical world, in the world of wind and water, of sea and mist and cloud, the world to which music – in its material nature as sound – itself belonged. He understood that, in our minds, music and nature are connected through a web of metaphors of movement, that we animate nature and music through the third term of language: the light dances on the sea, the music heaves like water. At the same time, he was captivated by the states of mind and body elicited by nature: intimations, fleeting impressions, elusive sympathies, but also feelings of exhilaration with life. One way to think about Debussy’s music is as an invitation to attention: at its most rapt, his music seems itself to listen, and the act of listening to which it draws us becomes the value of which it speaks – its ‘content’.

Debussy’s reputation has been smudged by the association of his music with words. Notions of indefiniteness, of the nebulous and vague, have attached themselves to a music that interests itself in these phenomena. The opening of Prélude à l’après-midi d’un faune may be an evocation in music of gentle, trance-like languor, of afternoon idleness, of lassitude even, but the music has a breathtaking rigour and exactitude. The clouds in Nuages may have indistinct edges, but the music that makes the analogy is cool and sharp. Once the superficial paraphernalia of descriptiveness is stripped away, Debussy’s music is revealed as almost abstract in its extreme concision, in its economy of means, in the sheer amount of ground that it covers within very short time spans. He spoke of his last creative phase as a return to ‘pure’ music (études, sonatas), but, despite its linguistic apparatus, all his best music is pure.

There is very little darkness in Debussy’s music and even at its loudest and most forceful it is rarely, if ever, brutal. Boulez would point out that the scene in Pelléas where Golaud drags Mélisande around by her hair is as sadistic and cruel as it gets. But this was an exception. The range of emotion in Debussy’s music extends from melancholy and wistfulness to ecstatic joy, but it stops short of pain; its energies encompass the hesitant fragility of the first movement of the Sonata for Flute, Viola and Harp, the exhilarating force of the climaxes of La Mer, the uncompromising ferocity of some of the piano Études, but it declines to frighten us.

Even at its most declamatory, Debussy’s music never hectors. The richest and densest piano textures – the climactic passages of L’Isle joyeuse or Feux d’artifice, for example – are acoustically magnanimous. En blanc et noir, so nimble and limpid, is a model of how to write wild music for two pianos. Debussy dreamed of a piano without hammers, of an orchestra without feet, and there is something in his music that does not like hard surfaces. One of its most characteristic traits is to cushion the impact of sounds, to disperse the energy of instrumental attack, through ornaments, grace notes, various forms of appoggiatura. The most common of these – a short-note/long-note rhythm with the accent on the short note, known in Baroque music as a Lombard pair (Walsh calls it a Scotch snap) – appears everywhere in his music, from quiet and sad pieces such as Des pas sur la neige to the most imperious passages of La Mer.

It’s tempting to ask what it was in Debussy’s life that led him to make these musical choices. What, as it were, was the shock he had to absorb? Despite his ramshackle family background, there’s no evidence that he had an unhappy childhood, though he must have seen things that a middle-class child would have been sheltered from. He always remained loyal to his parents, even as he moved into a quite different social milieu. Temperamentally, he was not easy: he was touchy and prickly and often curmudgeonly; he suffered fools badly and could be cutting. He was no good with money, whether earning it or keeping it, and his need for nice things (presumably a reaction to his lack of them as a child) was a mild addiction. He could lie when it suited him, especially when it came to musical commissions, and at times his promises to his publisher approached the fantastical (works would be publicly announced that he hadn’t even started). Photographs of him corroborate accounts of his saturnine, compelling personality, but there is a discernible sulkiness in his face and he could be childishly helpless and demanding with those near to him. He made and lost many close friendships. The women in his life were truer to him than he to them. His callousness towards them was perhaps not much wide of the norm for male artists of the time; what is surprising is how tolerant they were of him: his first wife, Lilly, shot herself in the stomach when Debussy left her for Emma Bardac, but, recovering from the physical wound, suggested a reconciliation. His strongest and least alloyed relationship was with his daughter, Chouchou.

He certainly had a darkness in him, a default moroseness that at times took a dive into despair (he more than once contemplated suicide). Throughout his career, he came back to Edgar Allan Poe’s story ‘The Fall of the House of Usher’. He first had the idea of writing an opera based on it in 1894, and as late as 1913 he was giving his publisher wishful accounts of his progress with the work, when in fact he’d hardly begun. Walsh observes that the ambience of Poe’s story, its atmosphere of gloom and menace, had already found its creative home in Pelléas: Debussy couldn’t write ‘The Fall of the House of Usher’ because he had effectively already written it. His inability to let the story go suggests that it spoke to him at some quite deep level, that he perhaps identified himself with the main character, Roderick Usher, whose pathological sensitivities, not least to music, are summed up in the two lines of poetry at the story’s head: ‘Son coeur est un luth suspendu/Sitôt qu’on le touche il résonne.’ In Pelléas et Mélisande, Mélisande’s first words are a frightened cry to Golaud: ‘Ne me touchez pas, ne me touchez pas.’

Touch is almost as important to Debussy’s music as sound. No composer has better understood the relationship between the two senses, the way in which the quality of any sound is both a function and an expression of the nature of the energy used to create it. Strauss thought Pelléas lacked ‘Schwung’ – swing, drive, oomph – and of course he was right. There’s still something provocative about the refusal of Debussy’s early music to engage phallic energy (just compare, as young man’s music, L’Après-midi d’un faune to Strauss’s Don Juan). His fixations would always be aural and tactile. Robin Holloway used to think that Jeux was ‘all about sex’, but that’s not really true of any of Debussy’s music (whatever being about sex might entail). It refers instead to the very earliest experiences of our lives, taking us back to the primal, magical time when we were lying in our prams or on a rug under the trees, watching the play of light among the leaves, feeling the touch of the breeze on our skin, hearing the sounds of insects.

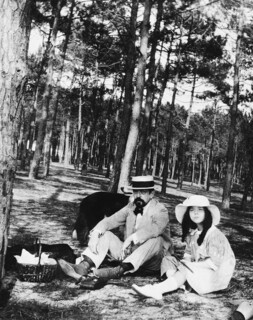

In September 1916, Debussy and his family spent a few weeks in Le Moulleau, near Arcachon. There’s a photograph (not included by Walsh) of Debussy and Chouchou sitting on the ground together in a wood. Chouchou, who would soon turn 11, looks at the camera from under a floppy white hat with a quizzical, intelligent gaze; Debussy looks ill and his darkly circled eyes speak of a man close to the limits of his endurance. Debussy and Chouchou had a deep affinity with each other. She was by all accounts a bright, talented, precocious child. In the photograph, she attracts and reflects light, while her father seems to suck it into himself. His life is over. She has it all before her. Except she didn’t: a little more than a year after Debussy’s death in March 1918, Chouchou died of diphtheria.

Edward Lockspeiser, in his two-volume biography of Debussy, includes a story told by the pianist Alfred Cortot, of how, some months after Debussy’s death, he had played some of the composer’s music to Emma and Chouchou and asked them their opinion of his playing. Chouchou was guardedly positive, but added: ‘Mais Papa écoutait davantage.’

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.