Ilya Kaminsky was born in 1977 in Odessa, the Ukrainian city named after Odysseus. In his first full-length collection of verse, Dancing in Odessa (2004), he let his readers in on a ‘secret’: ‘At the age of four I became deaf. When I lost my hearing, I began to see voices.’ When he was 16 his parents were granted asylum in the US and left ‘Odessa in such a hurry that we forgot the suitcase filled with English dictionaries outside our apartment building. I came to America without a dictionary, but a few words did remain.’ The change of worlds and the loss of the dictionaries enabled Kaminsky to invent his own definitions: ‘forgetting: an animal of light. A small ship catches a wind and sails.’ An émigré who cannot hear must have a strangely divided experience of a new culture. The new language will be unfamiliar, but I would guess that many of the habitual ways of reading people through signs, physical gestures and expressions stay the same. That may be the reason strong bodily gestures play such a big part in Kaminsky’s poems – dancing, kissing on the floor ‘among the peels of lemons’ – and why he often emphasises the physicality of communication: ‘In Odessa, language always involved gestures – it was impossible to ask someone for directions if their hands were busy.’

Dancing in Odessa includes a series of elegies for 20th-century Russian writers including Marina Tsvetaeva. In 2012, in collaboration with Jean Valentine, Kaminsky produced English versions of several poems by Tsvetaeva in a book called Dark Elderberry Branch. The volume is accompanied by a CD of recordings of the Russian originals, so that even the Russianless (like me) can enjoy the richness of Tsvetaeva’s language while reading the spare but delicious English translations. Kaminsky and Valentine convey the lyric intensity of Tsvetaeva’s love poems particularly well: ‘A kiss on the lips – is a drink of water./I kiss your lips.’ The master spirit of Kaminsky’s early work, however, is not Tsvetaeva but the most successful of all Russian-American poets. ‘I tried to imitate you for two years,’ he writes in his ‘Elegy for Joseph Brodsky’. ‘It feels like burning/and singing about burning …/You would be ashamed of these wooden lines.’

There’s nothing wooden about Kaminsky’s poetry now. It bursts with energy and can sometimes display internal stresses that make its texture shift and warp. Kaminsky wants to evoke the ecstasies of Tsvetaeva, to be as successful as Brodsky, and to communicate the experiences of Russian citizens under communism to his predominantly American readership. This mixture of aims means his verse always operates at a pitch of feverish intensity. Being Russian, for Kaminsky, means being the heir of Tsvetaeva (who hanged herself in 1941), her one-time lover Osip Mandelstam (who died in a transit camp in 1938) and Isaac Babel (who was executed in 1940). He takes on not just the burden of translating the political and erotic energies of 20th-century Russian poetry into a new language, but also a burden of historic suffering. There are moments in his early work when his shoulders seem to sag under the self-imposed strain. Take, for example, the title poem of Dancing in Odessa: ‘My grandfathers fought/the German tanks on tractors, I kept a suitcase full/of Brodsky’s poems.’ Are the two acts moral equivalents, or is keeping the suitcase a miniaturised version of ancestral heroism? Kaminsky himself seems unsure, and his writing sometimes displays a slight disappointment about his inability to replicate the wild ecstasis of Tsvetaeva – and perhaps about not having lived through Stalin’s terror.

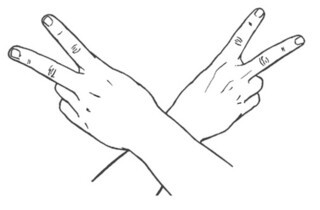

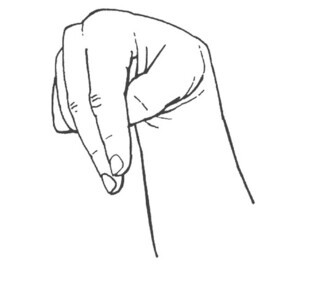

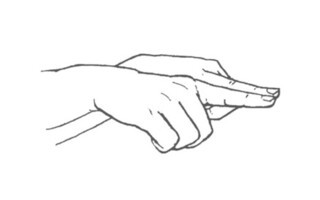

He reimagines that terror in his new collection, Deaf Republic (Faber, £10.99). It’s a sequence of lyrics, arranged as a drama, about events in the fictional town of Vasenka. Soldiers turn up during a puppet show and interrupt it; a deaf boy spits at them; he is shot and the people of the town go (or act) deaf as a form of resistance. They invent a new sign language (their gestures are illustrated in beautiful pastiches of a technical manual by Jennifer Whitten), a few of which are shown here, and hang puppets at the doors of those who have disappeared. The deaf boy’s cousin, a puppeteer called Sonya, resists arrest and is killed. Her husband, Alfonso, who narrates the first act of the drama, kills a soldier in revenge. He is hanged: ‘Urine darkens his trousers./The puppet of his hand dances.’ The owner of the puppet theatre, Galya Armolinskaya, leads a resistance movement whose members seduce and then kill soldiers. There are reprisals. She is also killed.

Deaf Republic is grim reading. It imagines a world in which everyone is complicit in murder. Its violent and distinct images recall Eisenstein’s Battleship Potemkin. Here is the first murder, of the deaf boy, Petya:

I watched the Sergeant aim, the deaf boy take iron and fire in his mouth –

his face on the asphalt,

that map of bone and opened valves.

It’s the air. Something in the air wants us too much.

The earth is still.

The tower guards eat cucumber sandwiches.

The cut to the guards with their sandwiches is harshly cinematic. But Kaminsky doesn’t just offer vivid representations of violence. In Deaf Republic the pressure of tyranny intensifies the dangerous delights of love to a surreal vividness – this aspect of Kaminsky’s work is reminiscent of Bulgakov, or indeed Tsvetaeva. Consider Alfonso’s description of his wife, Sonya:

You step out of the shower and the entire nation calms –

a drop of lemon-egg shampoo,

you smell like bees,

a brief kiss,

I don’t know anything about you – except the spray of freckles on your shoulders!

Relishing a moment, or a spray of freckles, can take over the entire world of Deaf Republic and replace oppression with ecstatic love.

After Snya and Alfonso are murdered, Galya, the organiser of the resistance, adopts their daughter Anushka:

So much to live for.

To bed, Anushka!

I am not deaf

I simply told the world

To shut off its crazy music for a while.

A disability can be a reason for persecution: the deaf in the deaf republic are regarded as sick and bundled away by the soldiers. It can be a means of resisting occupation by performing dumb insolence. But it can also be a way of shutting out the surrounding environment to enable the making of a private world, in which you can ask: ‘What is a child?/A quiet between two bombardments.’

‘For lyric poets and fairy-tale authors,’ Tsvetaeva wrote, ‘it is better that they see their motherland from afar – from a great distance.’ Deaf Republic re-creates Russia from the vantage point of contemporary America and hints at analogies between the two worlds. These analogies contribute to the disturbing power of Deaf Republic, but they can also generate the odd false note. The opening poem suggests that a silent war is underway in America and scoffs at its citizens’ half-hearted resistance:

And when they bombed other people’s houses, we

protested

but not enough. I was

in my bed, around my bed America

was falling

The final poem in the sequence returns to this supposedly ‘peaceful country’. It describes ‘a cop demanding a man’s driver’s licence. When the man reaches for his wallet, the cop/shoots.’ This takes us back to the murder of the deaf boy that set the drama in motion, and implicitly identifies Vasenka with contemporary America:

Ours is a country in which a boy shot by police lies on the pavement

for hours.

We see in his open mouth

the nakedness

of the whole nation.

We watch. Watch

others watch.

The body of a boy lies on the pavement exactly like the body of a boy –

The ending is again cinematic: on our phones we watch others watching, but do nothing. It also gives an uncomfortable edge of contemporaneity to the title of the volume: maybe the real deaf republic is not the one in which protesters become deaf as an act of dissent but one which refuses to hear, or respond to, what is going on inside it.

The implied parallel between Soviet oppression and American state violence is not intended to be comfortable, but it may cause discomfort in a way that Kaminsky does not intend. It raises a problem of scale: a bit like his uneasy juxtaposition of his grandfathers fighting the Germans in their tractors and his own suitcase full of Brodsky. How fully do the systematic murders and abductions in neo-Stalinist Vasenka equate to contemporary acts of police violence?

Kaminsky is honest enough to pose the question. But, because he can’t quite answer it, the two ‘American’ bookends to Deaf Republic are much less vivid than the depictions of violence and familial love that occupy its neo-Soviet centre. In the opening poem, an unspecified ‘they’ bomb the houses of unspecified people. In the final poem a ‘man’ is shot in a car, then suddenly becomes a ‘boy’ on the pavement. Is it the same person? Or is the change from man to boy in order to force an analogy with the deaf boy who was shot in Vasenka? That uncharacteristic vagueness in description hints at a problem with Kaminsky’s larger project. He draws inspiration from Mandelstam and Tsvetaeva, but knows that he lives in a different world. Reimagining the literature of Stalin’s terror carries two big risks. The first is trivialising catastrophic horror by comparing it to lesser horror. The second is appearing to exaggerate the ills of the present by forcing an analogy with events of a different order of magnitude. Probably no poet can fully overcome those risks, but Kaminsky is brave enough to take them on.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.