The catacombs under the Left Bank were originally part of a complex of stone quarries, built over as Paris spread during the 13th century. By the 16th century subsidence had become a serious concern and from the 1780s an ad hoc process of infilling began, with human remains from overcrowded or sinking cemeteries dumped in the galleries. Tourists now enter the catacombs near the metro station at Denfert-Rochereau in the 14th arrondissement; often the queues are long, especially around Halloween. But the ossuary occupies only a small portion of the old quarries and there are still pockets of the city’s heritage below ground worth excavating and curating. One of these, also at Denfert-Rochereau, is an air-raid shelter at a depth of more than twenty metres, built in 1938 as a nerve centre for civil defence services in the event of a bombing war. In August this dank warren of offices and passageways was opened to the public as part of the new Musée de la Libération de Paris, deep below the splendid Pavillon Ledoux. The main collection is displayed on the ground floor; a set of steps – about a hundred – leads down to the shelter.

When the internal resistance in the Ile-de-France called for a general uprising in the third week of August 1944, activists were able to get into the shelter and repurpose it as a clandestine command post during the critical days that followed, making use of the phone system (still operational), which linked them to the fire service, the water authority, the police and other security forces, and the city’s transport network. Expecting the imminent arrival of the Allies, workers and management were quick to respond. The police, the gendarmerie and thousands of transport and post office workers were already out on strike.

The figurehead of the uprising was Henri Tanguy, or ‘Colonel Rol’, a former steelworker and Communist Party militant who had fought in Spain: he took the nom de guerre Rol from a comrade in the International Brigades killed at the Battle of the Ebro. Tanguy returned to France, joined the army and after the defeat in the summer of 1940 went into hiding in the service of the party. In the bleary eyes of posterity, Colonel Rol-Tanguy, as he’s now officially known, was a good communist, or at least an excusable one, who took part in anti-Nazi activities ahead of schedule, while the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact was still in force. In the gung-ho movie Paris brûle-t-il? (1966), the script portrays him as a steely, mono-dimensional character, while fudging his communist affiliation. But we get the message. In one scene he slips through a doorway and heads for an air-raid shelter to take charge of the insurrection.

The underground area of the museum is mostly left to speak for itself, despite piped noises (footsteps, murmurings, sirens, phones etc): the explaining and exposition is done upstairs. The trouble with a collection of this kind is that it’s really a sort of book, moving from one episode to the next until it reaches a historic dénouement. Real books and most films handle this task without having to distribute narrative across three-dimensional space or needing to leaven dense information with glass cabinets full of memorabilia. One example: Jean Moulin, who unified the resistance on de Gaulle’s authority and died from the effects of torture in 1943 while he was being taken by train to Germany. So here we’re shown the matchbox he used to hide microfilm when he was parachuted back into France after a clandestine visit to London in 1942.

Not that the matchbox fails to work a certain charm. But it’s the many thousands of words on printed panels, detailed labels and complicated captions that visitors really need to put their minds to. Even the superb documentary footage requires glossing. Maybe this is why it feels like cheating to skip a paragraph and take a sentimental short cut via Colonel Rol’s German Army pistol or a tube of American shaving cream – yes, the Allies were on their way – or a lovely tricolore dress decorated with monuments of Paris and worn by a bystander for de Gaulle’s triumphal entry on 26 August.

The new museum has swallowed up two collections which went on show in 1994 for the fiftieth anniversary of the liberation. One was named for Jean Moulin and the other for General Leclerc, who led the 2nd Armoured Division into Paris. Both were housed above the Gare Montparnasse, where the footfall was disappointing: it makes sense to subsume them in a single museum, more accessible and more ambitious than their predecessors. But this has proved a headache for the curators, largely because Leclerc and Moulin are still the presiding figures, yet it’s hard to pair them: they never actually met. When Moulin was being interrogated by the Gestapo in Lyon, Leclerc was still in North Africa with the Free French; the 2nd Armoured Division had yet to be constituted. And of course you can’t be seen to underplay de Gaulle or ignore the rogues’ gallery of Nazi puppets and collaborators: enter Marshal Pétain, mysteriously central to the liberation of Paris. The museum’s full (and cumbersome) title acknowledges Leclerc and Moulin, but not Tanguy. Yet he was the man in the basement orchestrating the uprising, and to some extent he’s been kept underground. You only notice when you leave the museum that you’re on the avenue du Colonel Rol-Tanguy.

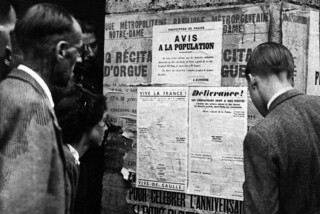

But the story is fascinating, whichever way it’s spun, and moves along at a pace. On 18 August the internal resistance plastered bills and flyers across Paris urging citizens to rise up. The following day, a Saturday, resistance cells in the police seized control of the préfecture on the Ile de la Cité. On Sunday barricades began to appear, the Hôtel de Ville was overrun, and Rol-Tanguy made his way to the air-raid shelter under the Pavillon Ledoux. His wife, Cécile, joined him later that day. Rol-Tanguy was already hitting the phones and doing what he could to manage dozens of initiatives across the city. It was now a question of holding out until the Allies arrived. Nobody knew when that would be. The 2nd Armoured Division had landed in Normandy three weeks earlier but Leclerc was still waiting for orders from the Americans to head for Paris.

By Monday the city was a shooting gallery; scores of resistance activists were dying as German units hung on. The military governor, Dietrich von Choltitz, had blown up the flour mills in the suburbs to stop bread production and was now laying explosives at key supply points and heritage sites in the heart of the capital. On Tuesday, 22 August, Leclerc received instructions to advance, but the roads were bad. Against Allied orders he decided to send a column up ahead: the 9th Battalion of the Régiment de Marche du Tchad, which had been swept up into his rank and file during his campaigns in Africa. These were not colonial African troops, as their name suggests, but mostly defeated remnants of the Spanish Republic who had made their way across the Mediterranean and re-enlisted in the anti-fascist struggle. On Thursday, 24 August, in the late evening, the 9th – known as ‘La Nueve’ – entered Paris. They were the first Allied soldiers to get there. Behind them came the rest of Leclerc’s division and the 4th US Infantry. By Friday the city was secured and Choltitz surrendered his command.

There were many scores to settle. Paris during the occupation had been a hive of collaborators and petty racketeers. The museum tackles all this head on. A newsreel clip shows Pétain in Paris in April 1944, touring the city after an Allied bombing raid as ecstatic crowds greet his motorcade. Detailed written material about reprisals after the Allied entry is set alongside harsh documentary footage. But we’re never allowed to forget that Paris was a ‘capital of resistance’ or that the odds were always stacked against its members. Rol-Tanguy calculated that 1750 fighters were the most he could hope for, equipped with revolvers, rifles, and around a hundred light machine guns, compared to twenty thousand German soldiers and dozens of tanks. In that decisive week the death toll among Parisians – resistance cadres and spontaneous insurgents – reached at least fifteen hundred. The dead were honoured and the living praised to the skies. One mesmerising film clip we can watch again (and again) at the museum shows Anne-Marie Dalmasso, a 22-year-old Italian member of the resistance, as she runs from the Hôtel de Ville during a skirmish and expropriates a rifle from a wounded German soldier. That impulsive dash across the concourse turned her into a legend.

No museum can give us a sense of the occupation as it was experienced, day by day, by millions of people caught between varying states of complicity and outright defiance. Filmmakers – Truffaut, Jean-Pierre Melville, Marcel Ophüls, Louis Malle, Claude Berri and recently the creators of Un village français, a seven-season blockbuster for France 3 – have handled the business of improvisation and negotiation much better. Writers were quicker still to understand the pull of agnosticism when bravery has become a cult. In 1945 Sartre described how easy it was for citizens to get used to an occupying army. ‘Over time a kind of shameful and indefinable solidarity grew up between Parisians and these [German] soldiers who were, deep down, so similar to French soldiers’: ‘We were squashed together in the metro, we bumped into them in the middle of the night.’ For most Parisians, rubbing shoulders with the Germans made it difficult to hate them without hatred becoming another burden.

Over time the meaning of defeat and all that followed has changed. The titanic stand-off between Gaullism and communism did much to shape France’s troubled sense of the occupation through the 1970s and the first Mitterrand administration. The fall of the Soviet Union and, now, the demise of traditional left and right parties in France have drained the energy from this ideological contest. At the same time, historical research has brought into focus the role of minorities in the liberation, including Jewish resistance members, women, immigrants and internationalists, among them figures like Dalmasso and the Spanish Republicans: as part of this year’s anniversary celebrations a sequence of large pop-up murals honouring La Nueve appeared near the Salpêtrière.

Africans and African Americans are absent from this multicultural tableau: the Americans decided to ‘whiten’ their own contingents before they entered Paris, and foisted the policy on their junior partners. Black soldiers were purged from all Allied ranks for the occasion. The only one you’re likely to see in the archive is fictional: he appears as an extra in Paris brûle-t-il? A racialised fear that victorious non-whites and colonials would overdo the revels in Paris seems to have haunted the Americans. Later, as the Free French pressed forward into Germany, de Gaulle dismissed thousands of seasoned troops recruited from outposts of empire on the grounds that people of colour might suffer from the cold as winter drew on. In reality he had to clear space in the army for demobilised resistance members as quickly as possible: no good would come from leaving the communists at a loose end in liberated France.

The museum looks set to become the gateway to a constellation of memorial sites in the Paris area: the National Resistance Museum in Champigny, the Gaullist monument to the fallen at Mont-Valérien and two impressive Holocaust memorials. The first of these, opened in 2005, contains a vast card index file kept by the Nazis and the French authorities: 76,000 Jews were rounded up in France, most of them murdered in Auschwitz and Birkenau. The index is on view in a chamber at the side of a magnificent crypt with a marble Star of David commemorating all six million who died in the Holocaust. The files are on loan from the state archives. A second site opened in 2012. It overlooks La Muette, a housing project in Drancy begun in the 1930s and still unfinished when it was requisitioned by the Nazis as a transit camp for Jewish deportees. It has since become a desirable housing estate, in a banlieue with many first, second and third-generation immigrants, many from Muslim-majority countries. The permanent collection, understated and entirely to the point, is housed in a first-floor room with an enormous curving window. Every dark detail of the past is recorded as dispassionately as possible. As the light pours in through the window it’s tempting to turn away from all the painstaking evidence. But when you look down at the residents moving around the housing project, you can still see the contours of the camp.

Sometimes people slated for deportation would be taken inexplicably from Drancy and driven away in trucks. Their destination was Mont-Valérien, a grand hilltop fortress west of the Bois de Boulogne. During the occupation, the Germans executed 1008 people here as part of a quid pro quo policy. After significant resistance operations, inmates would be removed from detention centres in the Paris area, including Drancy, and taken to the fort to be shot. Many were killed on arrival. Others had to wait for an execution detail to be put together. A little chapel was used as one of the holding areas and graffiti from the original stucco wall have been preserved. Some are addressed to family members; one speaks to the bleak prospect of abstinence in death (‘bons baisers à ma femme’); others signal the cause for which they are about to die. ‘Vive la France’; ‘Mort pour la France’; ‘Vive l’Union Soviétique’; ‘Vive le parti communiste.’ The people executed at Mont-Valérien were mostly communists and all were men, but many female resistance members were deported to Germany. Nine, as far as we know, were guillotined there. Shooting seditious women in situ was thought to be ungentlemanly: better to expedite them to Germany and cut off their heads – the guillotine was one of many French traditions the Nazis admired.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.