Lucian Freud’s mother, Lucie, brought her three sons from Berlin to London in September 1933 when Lucian was almost 11. She was soon followed by her husband, Ernst, an architect and the youngest son of Sigmund Freud. Over the next five or six years, more members of the family, including Sigmund himself, came to England, where their papers were organised by Marie Bonaparte, who put in a good word with the Duke of Kent. Four of Sigmund’s sisters stayed behind in Vienna and perished in the concentration camps: Dolfi, of starvation, in Terezín, Rosa in Auschwitz, Pauli and Mitzi in Treblinka.

Lucian Freud was sent to a boarding school where students didn’t have to study if they didn’t want to. There were no marks or prizes, and no punishments were imposed. John Betjeman described it as ‘a co-educational school to which modern authors and intellectuals send their sons’. Freud had no interest in academic subjects. Instead, he was fascinated by horses, and remained fascinated all of his life. One of his school reports read: ‘Lucian doesn’t seem to have mastered the English language but is fast forgetting all his German. This seems to be quite a good argument against his taking up French.’ His handwriting ‘was, and remained, unschooled’, William Feaver writes in his new biography, and adds: ‘Having to learn to write with his right hand in a new language and a new script prompted him to feel that such discipline, being foreign to him, was not for him. This became his pattern of behaviour at boarding school and, later on, in London: wilfulness passed off as extreme individuality. He came to regard England as a place in which to be a lone operator.’ His time at another school ended because of a rule that every boy should make his own bed. Domestic chores were not, and would never be, Freud’s thing. His laundry was done by a friend called Jane all his life. ‘I don’t think he had the faintest idea what laundry was,’ Frank Auerbach said. ‘He put it into this basket and it came back from Jane immaculately laundered.’

After he left school, his father took a piece of sculpture – a sandstone horse, almost two feet high, ‘three legs serving convincingly as four’ – that Lucian had made, to show to the Central School of Art. Lucian was accepted as a student. His mother was proud of the piece, and displayed it on the mantelpiece. ‘My mother started worshipping it so I smashed it,’ he said. When his father introduced him to a potter friend, he said: ‘This wild animal is my son.’

The wild animal received helpful advice from some of his teachers, one of whom told him that the thing to do before parties is to ‘toss yourself off in the taxi to make your eyes shine.’ The same man also advised him to ‘step up production to, ideally, a picture a day’. His early paintings, Feaver writes, are ‘naive in that they appear untouched by, indeed oblivious to, academic discipline’. Over the next few years, as he moved around London, enjoying its pleasures, he spoke of himself as a painter. Later he explained that this was what started him off. ‘The image had to be substantiated,’ Feaver writes.

Once he was in his late teens, it became fashionable to fall in love with Freud. When Stephen Spender, according to himself, told T.S. Eliot that he had succumbed, Eliot said: ‘There’s nothing I understand more.’ Spender and Freud spent some time in a cottage in Wales when Freud was 18 and produced a little book of drawings and poems together. (Years later, Freud cut the Spender poems out of the book, ‘deeming them superfluous’.)

Peter Watson, who funded Horizon, also began to enjoy Freud’s company. ‘He helped me very much, looked at my pictures and bought things and gave me money and books,’ Freud said. ‘He had pictures that I liked and learned from, very good things … He had a marvellous kind of abandon. His queerness didn’t affect me; the gay world was more assimilated then, I mean for me: it wasn’t something people made a feature of.’

Freud’s uncle, who was an art dealer, ‘obviously thought I was queer … and told my father I was mixing with very disreputable and dangerous people’. Ernst Freud could do little: his son didn’t bother much with his family. He disliked his brother Clement, enjoying the fact that he worked as a waiter at the Dorchester. ‘I quite liked him being the waiter; he was rather a good waiter. Dressed in white he was OK.’ Some years later, in France (‘I may have a sadistic streak, I think’), he encouraged Clement to take a ride on a helter-skelter: ‘I was down below watching him go round, roaring with laughter at his fear and anger; he couldn’t get off he was in such a state.’

When Freud was in hospital once, his mother came to visit. ‘It was good because I had such strong sedatives I was asleep when she came.’ Later, when he moved to Delamere Terrace in Paddington, considered a dangerous part of London, she ‘used to go daringly down there and leave me food parcels on the step. I never liked having her round. She never called in.’ When he went to see his father to get money, his father would ask him to look in on his mother. ‘I’d say yes and go straight out. It was being forgiven I didn’t like. My mother always put nobler motives on my actions than those they were actually prompted by.’

When Sigmund Freud died in 1939 he left the proceeds from his copyrights to his grandchildren, which, since the royalties were sizeable, gave Freud a basic income. Another part of the old man’s legacy was that it encouraged people to feel that his grandson cared about their unconscious, which he did not. One girlfriend would tell him her dreams, presuming that, as a Freud, he would be all ears.

Early in 1941, Freud joined the Merchant Navy. He was the youngest of a crew of sixty and used his talents to design tattoos for his colleagues. After four or five hair-raising months he was discharged due to ill-health. ‘Over the years,’ Feaver writes, ‘as his seagoing exploits ballooned into legend, questions were asked. How precisely had he obtained his discharge? Was it true that he had murdered the ship’s cook?’ There were also rumours – Freud blamed Spender for spreading them – that, after this stint, he avoided being conscripted because he couldn’t handle being separated from his cat. ‘Stephen always embroidered. That’s how it got about. My strength has been on the solitary anarchic side. A psychologist’s report called me “a destructive force in the community”.’

In London on the loose, Freud had a good war. ‘You couldn’t go out in the blackout without getting the clap,’ he remembered. In descriptions by himself and others, he emerges as a feral young fellow who did not let much bother him. But there are interesting moments when he takes a moral position; for example, when Dylan Thomas, who annoyed him by making assumptions about his relationship with Spender, irritated him further by boasting how well he, Thomas, had done out of a visit to Peter Watson to touch him for money. ‘I thought that was a despicable attitude,’ Freud said. ‘I’ve never been alive much to repercussions.’ His response might also have been affected by Thomas’s opinion that two drawings he exhibited in spring 1942 were rubbish. Freud liked borrowing money and didn’t worry about it. ‘Sometimes,’ he told Feaver when they were discussing his borrowing habits, ‘I think you make me more moral than I am, less amoral than I am. I don’t suffer from guilt.’

By 1945, it was clear to his father that Freud was to become a painter. Ernst had considered the same vocation. To his own father, Sigmund, he had said, or so it was reported: ‘One should either regard painting as a luxury, pursuing it as an amateur, or else take it very seriously and achieve something really great, since to be a mediocrity in this field would give no satisfaction.’ Lucian Freud’s comment on this lovely piece of high-mindedness is: ‘It always seemed understood.’

Freud died in 2011 and the amount of first-hand information available about his antics means that Feaver could easily have written a book filled to the brim with gambling sprees and babies, as well as egocentricity, carelessness, fecklessness and an interest in danger. And while he has indeed filled his book to the brim with the excitement and strangeness of Freud’s life, he sees him as painter rather than playboy, or rather he agrees with Freud, who told him: ‘Everything is biographical and everything is a self-portrait.’

Feaver has a vivid sense of the sheer amount of time Freud spent in the studio and the determination and independence of mind that kept him charged. He is alert to the idea that the energy Freud spent on his work spilled over into the night, into sexual adventures, gambling binges, social climbing (up and down). The fact that convention didn’t bother Freud made him, of course, a lousy father, a financial headcase and a domestic nightmare, but that very failure to conform also made him single-minded in his attempt to explore a way of painting that might satisfy his own standards. The lack of complacency in the way he conducted his social life was matched, or indeed inspired, by the lack of complacency he showed in the making of a picture. This connection between forms of energy poses a dilemma to a biographer. It offers him or her the chance to ask many dull questions, most notably: does the fact that Freud was a genius excuse his behaviour? Feaver sidesteps this question, letting us know what happened without becoming a moralist. He remains sober, balanced. He uses his extensive interviews with Freud subtly and judiciously.

In 1945, when Freud asked Graham Sutherland who the greatest painter in England was, Sutherland responded: ‘Oh, someone you’ve never heard of: he’s like a cross between Vuillard and Picasso; he’s never shown and he has the most extraordinary life.’ He was referring to Francis Bacon. That year, Bacon exhibited Three Studies for Figures at the Base of a Crucifixion. After the two met, ‘the friendship,’ Feaver writes, ‘was to spur Freud for the next thirty years … Bacon was, he said, the “wildest and wisest” person he had ever encountered.’ In 1948, he bought his first painting by Bacon; over the years he was, on and off, to own nine, one of which he referred to as ‘The Buggers’ and hung on the wall opposite his bed. He enjoyed Bacon’s company, but, more important, he paid attention to what Bacon had to say about paint:

He talked a great deal about the paint itself carrying the form, and imbuing the paint with this sort of life; he talked about packing a lot of things into a single brushstroke … The idea of paint having that power was something that made me feel I ought to get to know it in a different way that wasn’t subservient. I wanted to see what it could do.

‘By the time the war ended,’ Freud said, ‘I was longing to go to Paris. I went in 1946 when you were allowed to go … It just seemed amazingly exciting.’ While there, he had an affair with Michael Wishart, who was 18 – Freud was 23 – and a nephew of a woman Freud had been close to, and a cousin of the woman who would be his first wife. Wishart, who became a painter, would marry Anne Dunn, who was also a lover of Freud’s. In Paris he worked on drawings and paintings. ‘I set certain rules for myself and I suppose those rules were exclusive. Never putting paint on top of paint. Never touching anything twice; and I didn’t want things to look arty … I wanted them to look as if they had come about on their own.’

When he showed at the London Gallery in Brook Street in 1947, the reviews were not warm, one critic writing of ‘a quality of Germanic linear accuracy of the kind we associate with Albania, with a perfectly planned introduction of apparently irrelevant detail which is typical of some of the Surrealists’. A year later, when his Girl with Roses was on show at the same gallery, the painter William Townsend noted that it ‘looks like the work of someone quite simple-minded – using simple in the right sense – pressed by the business of tracing out his subject in all its particularity, down to the last irregularity of the sitter’s fingernails’.

In July 1948 Freud married the heavily pregnant Kitty Garman, the subject of many of the portraits from the previous few years. She was the illegitimate daughter of the sculptor Jacob Epstein. The couple set up house in St John’s Wood, but Freud kept his old quarters at Delamere Terrace. According to one of his constant companions, ‘Lu would tell Kitty that [we] were going to work together when really [we] worked an hour or so then would “go down the West”.’

Freud did not take to married life. A friend noted that Kitty, having made dinner, ‘had to sit with her face to the wall while he ate as he couldn’t bear being watched eating’. He left soon after their second child was born. ‘So I moved to Delamere. I remember lying on the couch there, first night, mice all around me, thinking this is the bachelor life.’ He didn’t get on with the mothers of the women he was seeing. He had grown to hate Kitty’s mother, and Anne Dunn’s mother hated him: ‘She couldn’t bear the way he moved. He’d sidle in through the front door, he’d come in like a crab and she’d say: “What’s that rat doing in the flat?”’ Dunn herself was enchanted by him: ‘Life without Lucian would have no meaning whatsoever. He was the sun and he managed to downgrade and diminish everyone else in his eyes. In removing himself he removed the reason for existence.’ She compared him to his grandfather: ‘One doesn’t walk into a victim situation but if one perhaps had been victimised in one’s childhood Lucian was quite productive at bringing that out. I think he looked very like his grandfather and behaved like his grandfather. The same control. One was clipped onto a dynamo.’ Freud did a heart tattoo on her thigh and showed her how to hang onto the back of a lorry while cycling.

When Freud was painting Sleeping Nude, using Zoe Hicks, an illegitimate daughter of Augustus John, as the model, he made sure Dunn was out of the way. ‘On the landing there was a bath where he kept coal and I never understood what was happening, quite why I was being locked in there.’ When Patrick Heron saw the painting at the Hanover Gallery in 1950, he wrote: ‘One is not sure. Terrific finish, no longer being idiosyncratic, cannot hide an uncertainty, not of drawing but of volume. And then there is a new element here: this work is atmospheric for the first time in Freud’s career.’

As his work became better known, Freud began to hang out with posh people, including the Rothermeres, who owned the Daily Mail. (He painted a portrait of Ann Rothermere, who married Ian Fleming in 1952.) He got to meet Garbo and dance with Margot Fonteyn and socialise with Princess Margaret. He got to disappear into the night with Simone de Beauvoir, whom he met in a club. ‘He enjoyed the perks of being an artist,’ Feaver writes, ‘authorised to stare, to roam freely throughout society, to enjoy a freedom that his parents could never fully experience and his brothers barely.’

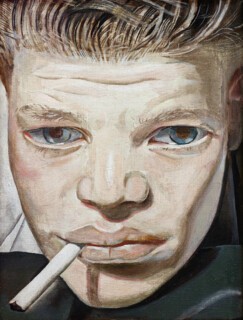

While he seemed to like the high life, he liked low life more. Charlie Lumley is one of the low-life figures who flits in and out of this narrative like a boy out of Dickens, and is the subject of paintings such as Boy Smoking (1950-51) and Man’s Head (1959-60). ‘He took a long time to paint my picture,’ Lumley remarked. ‘Three years. Course a lot of the time I was in and out of jail.’ ‘We were generally known as friends,’ Freud said. ‘We got on very well. Sometimes things that I didn’t understand Charlie would explain to me: the harsh ways and laws of the life [in Paddington], such as the things people were respected and despised for.’ He and his friends were ‘always fighting and shouting … I heard this clinking in his jacket; it was a knuckleduster and I took it out; next day he came back with an eye almost out and I felt bad.’ Anne Dunn remembers Lumley stealing a watch belonging to a friend. ‘There were serious raids on the Spenders’ house when L. was in his “Genet” mode with Charlie.’ Freud thought that was bad-mouthing his friend. ‘I looked after Charlie. I made his life much easier: money and comfort. He was good company. He seemed to get into trouble more when I went away … I really got nice letters from him in prison.’

Frank Auerbach, who met Freud in 1955, wondered about this relationship, saying that Bacon had told him ‘that Lucian had told him that sometimes he woke up – and it’s not entirely rare in Lucian’s life – in the same bed as Charlie and thought, oh yes, it was only Charlie, and turned over’. Some of Charlie’s letters display a genuine interest in what Freud was painting, but he had other uses. At a party, for example, when Freud spotted a girl he liked and wanted to get rid of the girl’s boyfriend, Charlie obliged by throwing the fellow down the stairs.

Freud planned to use Charlie for his painting Interior at Paddington, but he was doing National Service, so instead he used Harry Diamond. At the time the painting was made, in 1951, Diamond was working as a stagehand and thus was free during the day. For six months, he stood as instructed in Freud’s studio. When he saw the painting, he said that his legs were too short. ‘His legs were too short,’ Freud responded. In Man with a Blue Scarf: On Sitting for a Portrait by Lucian Freud, Martin Gayford reports that Freud told him that when Andrew Parker-Bowles protested about the way his stomach protruded, Freud ‘thought I’d better emphasise it more’.

Freud met Caroline Blackwood at a party in 1949 when she was 18. Three years later, he painted her portrait. Just as John Minton had commented when Freud painted him, Caroline, of whom Freud did a series of portraits, remembered ‘the amazed interest that he once took in the human vulnerability of his sitters. The portraits he did of me were received with an admiration that was tinged with bafflement. The results were only half-me, I think – after all it was Lucian’s vision.’ She wrote years later of his ‘genius ability to make the people and objects that come under his scrutiny seem more themselves, and more like themselves, than they ever have been – or will be.’ Her mother found Freud’s interest in her, Feaver writes, ‘repulsive and alarming in that, to her, Freud was the embodiment of pretty well everything she most loathed: poor and spivvy, and Jewish, a painter too and married.’ In order to make clear the general opposition among the posh to her consorting with Freud, Nancy Astor pulled Blackwood’s hair. ‘Don’t you think it’s disgusting when old women attack young women?’ Blackwood wrote to her afterwards. ‘Anyway, I THOUGHT YOU WERE DEAD.’

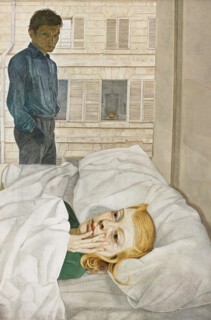

When Blackwood moved to Spain, Freud sold ‘one of my two paintings of bananas’ and used the money to go after her. He had the door number of the place where she was staying, but not the name of the street: ‘I knew she lived at 85 something and went round knocking on all the 85s.’ In 1953 they married. But ‘with marriage came deflation.’ In Paris, Freud painted Hotel Bedroom, in which Caroline is in bed while Freud himself, in shadow, stands watching her warily. ‘Day after day,’ Feaver writes, ‘through the winter she lay there, frigid under his scrutiny.’ While they were there, Anne Dunn reappeared. Though married to Michael Wishart, she remained, as Feaver writes, ‘susceptible’: ‘Of course then we took up again. Then I got pregnant and … had an abortion, the third or fourth abortion of Lucian’s.’ Caroline became ill. ‘There was a fight,’ Feaver writes, ‘during which he pushed her naked into the hotel corridor and locked her out.’

When Hotel Bedroom appeared in London, destined for the Venice Biennale, the catalogue essay by Robert Melville said of Freud, among many other offensive things: ‘in England we look upon him as the finest of our living primitives. His art has the exquisite laboriousness of Sunday painting relentlessly pursued throughout the week.’ When the critic and collector Douglas Cooper saw the works at the Biennale, he wrote that Freud’s ‘faulty draughtsmanship and his modernistic distortions (contrasting oddly with the naturalism of his pretty-pretty flower and fruit still lifes) produce paintings that are affected rather than forceful’.

‘For Freud,’ Feaver writes, ‘the dwindling of his second marriage more or less coincided with the period during which his “gadding about”, as he put it, resulted in births and related complications.’ ‘Sometimes,’ Anne Dunn said, ‘instead of counting sheep, I count Lucian’s children.’ Suzy Boyt had four children by him, in 1957, 1958, 1960 and 1969. He had four more with Kay McAdam, one born in February 1958, another in April 1959. One Christmas many years later Boyt said to him: ‘I’d like to thank you for the children.’ ‘I can’t help noticing that some of my children are born awfully near each other, from different mothers,’ Freud said to Feaver. ‘All one can say is that’s how it was. You ask me why are these children all the same age. Don’t you realise I had a bicycle?’

He didn’t see many of the children when they were growing up. For a long time the McAdam children did not know that Freud was their father. ‘I got a covenant made when I hadn’t any money so that they always had some money. They don’t know that.’ His mother sent monthly cheques and generous presents: ‘She was very altruistic and had a very noble motive. I kept out of the line of fire.’ When McAdam needed money and threatened to complain to his parents, Freud dropped her completely. ‘If you’re not there when they’re in the nest you can be more there later,’ Freud claimed. ‘I have feelings for my children as they’ve grown up. I haven’t had a domestic life.’ Some of his brood became figures in his portraits.

Freud’s portrait of Suzy Boyt, Woman Smiling (1958-59), was ‘a venture into animated expression’, Feaver writes. He worked towards ‘more variety of effect, different strokes for the pull, the sag, the sheen of skin, and the tight whitening where boniness shows through … He wanted to be able to achieve more immediacy, more fullness, more body.’ As he struggled to give the paint more autonomy and force, he worried when people liked his work.

I’ve never minded being overlooked or forgotten. It wasn’t that I was abandoning something dear to me … I felt that the linear aspect of my drawing inhibited what I wished to do in my painting. Though I’m not introspective I think all this had an emotional basis. It was to do with the way my life was going and to do with questioning myself as a result of the way my life was going.

Freud’s first exhibition at Marlborough Fine Art in 1958 didn’t please John Berger, who thought the paintings were ‘like touched-up photographs of rotten apples … They appear to be fashionable but are worth very little.’ Lawrence Alloway, then the assistant director of the ICA, complained that ‘the new portraits reveal a disastrous interest in painterly values.’ Gayford writes well in Man in a Blue Scarf about the change in Freud’s work in this period, a move from making paintings that depend on the line to paintings that depend on the brushstroke. He compares the portrait of John Minton, done in 1952, to that of John Deakin, done more than a decade later: ‘The former is so sharply defined that one feels one could count every hair of Minton’s head; the latter is so broadly executed that, on the contrary, you see the marks of the bristles of the brush in the broad scoops and whorls that make up Deakin’s face.’ He also notes that the change in style ‘was manifested in an alteration of brush: previously he had used sable, afterwards hog-hair.’ This change in his work alienated Kenneth Clark, among others: ‘He wrote a card saying that I had deliberately suppressed everything that made my work remarkable, or something like that, and ended: “I admire your courage.” I never saw him again.’ Among Freud’s supporters was Auerbach, whom Feaver quotes: ‘Lucian just carried on in his own way and knew exactly what he was doing and what he was heading for: what turned out to be an enormous gap in art history where there isn’t anything like Lucian’s lumps of flesh and human animals … With Lucian it was absolutely new and nobody recognised it.’

Freud, Feaver writes, ‘painted his sitters just as they were, just where they happened to be, in whichever room was serving as his studio, aiming to accomplish paintings that held true’. He didn’t make preparatory drawings. In the case of Gayford, he began with the forehead and worked painstakingly downwards. As he attempted to paint the face and the whole body, Freud’s lack of rigorous training became clear. Feaver writes of a painting of Jane Willoughby – the woman who did his laundry – from 1962 ‘in which the head, the character part, sits uneasily on the body’. Freud viewed this painting, and other ones like it, as ‘write-offs’.

What rescued him was a system of working with what Feaver calls ‘vigilance and abandon’. Perhaps the most telling moment in his book is the speech Freud made to students in Norwich in 1964:

You’ll be dead very soon and I want you to do naked self-portraits and put in everything you feel is relevant to your life and how you think about yourself and not think that this is a picture on the way perhaps to doing a better picture; I want you to try and make it the most revealing, telling and believable object … Take off your clothes and paint yourself. Just once.

Jeffrey Bernard remembered Freud once putting £500 on a horse. ‘During the running of the race never have I seen a man so adrenalin-filled. Not white, he looked almost transparent with nerves.’ The owner of the Marlborough remembered him taking more than £4000 – others said it was £2500 – from the gallery to the betting shop and losing it in a few minutes. ‘I want to change things with the bets,’ Freud said. ‘Either be dizzy with so much money or otherwise not have my bus fare.’ In his interviews with David Sylvester, Francis Bacon connects chance in gambling with chance in making a painting. What Freud did seems more deliberate, less open to chance. Because the process was slow and delicate, involving many small decisions in the mixing of paint and the creation of texture, a small lapse could be corrected, as a horse race or a bet could not. (‘I like to think that everything in the picture is changeable, removable and provisional,’ Freud told Gayford.) It’s not as though Freud’s gambling actually fed the paintings, but rather that the excitement of what he did outside the studio fired the nervous system, and he worked from that when he went to paint.

The element in Freud’s character of ruthlessness and dark wilfulness did not merely create havoc in his personal life, it gave him steel and determination in the management of his work, until his work became his life. (For about fifteen years, Freud and Auerbach would have a meal on the afternoon of Christmas Day. They would both have spent the morning working in their studios.) This devotion to work had its dangers. ‘The thing is,’ Freud said, ‘if you spend your time working and have no time for courtship and flowers,’ then you are more likely when you go out and find someone to get the ‘clap’.

Feaver’s book shows how easily Freud could have become someone else: a painter of society portraits, for example, if he had been willing to soften his style; even a painter of pretty still lifes and flowers. (The Marlborough wished he would do more flowers.) He could also have become a professional sponger, a troublesome presence in bars and clubs, someone who used to paint. (There were many examples in his London world – John Minton, Robert Colquhoun, Robert MacBryde, Michael Wishart among them.) As a way of steeling his nerve, the example of Bacon, who relished his own untidy life as he sought perfection and excitement in the work, must have been useful. Auerbach’s solid application to painting must also have been of some help. Watching both of them persevere as fashions changed, and Abstract Expressionism became all the rage, not to speak of Pop Art, must also have been of assistance.

Freud only named his sitters when they were public people; otherwise he put a generic title on the painting. It was ‘partly to do with privacy’, he said, ‘but it also seems to me to be pretty irrelevant. Portraits are all personal.’ Feaver fills us in: it’s an advantage that he’s writing a biography of a painter. In biographies of writers, there is something both dreary and false about trying to identify the people on whom fictional characters are based. It is fascinating, having read his book, to open a catalogue of Freud’s work and to see portraits of Kitty Garman, Caroline Blackwood, Charlie Lumley, Jane Willoughby, the artist’s mother – the whole cast of characters. Knowing how Freud met these people and when he painted them and who they were adds enormously to the interest in looking at the work. But no matter what we know or don’t know, the paintings hold their strength, their mystery, their distance. Freud, too, in Feaver’s version, maintains his own strength, his mystery, his distance. His biographer makes no effort to delve into his inner being and explain his work accordingly. Freud’s outer being gives him more than enough to go on.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.