Comics emerged in Japan ‘at least a century earlier than in Europe or the Americas’, according to the catalogue for the Manga exhibition at the British Museum (until 26 August). Today, the term ‘manga’ describes a drawing style seen in comic books, graphic novels, video games and animations but its origins are in the late Edo period (c.1750). Woodblock prints called ukiyo-e, ‘pictures of the floating world’, were used to create serialised works bound in ten or twenty-page volumes, each page with a single image and block of text. They were initially aimed at children but quickly became tools of gossip and intrigue, often referring to contemporary actors, poets and politicians. Between 1775 and 1806, more than three thousand comics for adults, or kibyōshi, were created – around a hundred a year. Contemporary Japan has a word for people who consume comics obsessively, otaku; Western manga fans have reclaimed it as a term of endearment but in Japan it is a pejorative. In the late 18th century, kibyōshi protagonists such as Tōfu Kozō (Tofu Boy), a squat superhero whose weapon of choice is a plate of tofu, made their way onto hand towels (Japanese often carry their own), shop signs and blankets; some were even carved into netsuke. Obsessive nerd culture is not a modern phenomenon. Adam Kern, who has written books about kibyōshi, argues that they were ‘consumed with a zeal rivalling that of today’s otaku’.

The ukiyo-e artist Hokusai adopted the word ‘manga’ early on: the first volume of his Hokusai Manga was published in 1814. It was a money-making scheme, intended to attract paying pupils to his classes, but the sketches were so popular that he completed 14 further volumes. They aren’t obvious precursors of modern manga: his drawings of workers, ghosts, gods, birds and rabbits are a literal expression of the word itself, combining the Japanese characters for man (‘random’ or ‘run riot’) and ga (‘pictures’), and there is no narrative. But they do possess similar characteristics. Hokusai’s manga can’t stay still. His casual sketches of people at work – masseuses, samurai, blacksmiths – quiver with implied movement. In the postscript to One Hundred Views of Mount Fuji (1834), he wrote that, aged 73, he ‘partly understood the structure of animals, birds, insects and fishes, and the life of grasses and plants’. By the age of ninety, he said, his work would have progressed to penetrate the ‘secret meaning’ of life and, by his hundredth year, ‘the level of the marvellous and divine’. ‘When I am 110, each dot, each line will possess a life of its own.’

Hokusai died at 88, but the best manga fulfils his 110th birthday wish. His drawings, and those of his contemporaries, set the precedent for modern manga’s reliance on action, rather than language, to drive the narrative. A scene from Hokusai’s One Hundred Ghost Tales (1833), displayed at the start of the exhibition, depicts the skeletal remains of Kohada Koheiji, murdered by his wife’s lover, now returning to their bedroom to seek revenge. It’s a nice example of Hokusai’s skill as a storyteller and of a work that shares some of the techniques of modern comics. Kohada appears as a caricature skeleton, his teeth upturned into a wicked smile within his skull; his eyeballs are intact, wide and frank as in modern manga. The pinch of the curtain beneath his fingertips foreshadows the horror to come.

In its purest form, manga refers only to serialised comic books, always black and white and read from right to left, back cover to front cover. At the entrance to the exhibition, a series of prints from Giga Town: A Catalogue of Manga Symbols by the artist Kōno Fumiyo explains this reading style and introduces manpu – the language of visual cues manga uses to propel its narrative. Gappy parallel lines running horizontal behind an object suggest that it is moving at great speed; tight, vertical lines on the face of a character, or as a backdrop to a scene, indicate ‘darkness/fear/sadness’. Speech, when it appears, is to be read differently depending on the shape and size of the bubble that encases it. Some are self-explanatory: a spiky bubble indicates exclamation. Others are less clear: a voice ‘echoing in the head’ – a deity perhaps, or a malevolent spirit – appears as free-floating text encircled by thin strokes. The subtle, percussive style of manpu sets manga apart from the crash-bang-wallop of American superhero comics. Perhaps some of these signals linger from the ukiyo-e period, when a language of lines must have made for a quicker and cheaper process than carving characters.

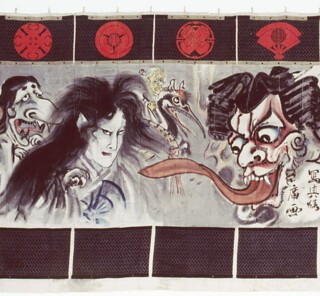

Manga artists work in the knowledge that the printed book is all that matters and the original drawings will remain unseen – unless they are fished out years later for display in a museum (one of the pleasures of this exhibition is seeing the marginalia, rough sketches and printers’ instructions on the original drawings). But the act of drawing is revered: a video clip of the artist Higashimura Akiko working on Snowflake Tiger celebrates her ability to ‘draw at speed’. Watching manga artists draw is its own entertainment; some livestream themselves working – hours of video footage are available online. Hokusai himself performed drawing too. At a public festival in 1804, he used a broom and buckets of ink to paint a 180-metre-long portrait of the Buddhist monk Daruma. A 17-metre-long theatre curtain by the artist Kawanabe Kyōsai, painted over the course of an evening in June 1880 and littered with wide-eyed spirits and ghosts, dominates the far wall at the British Museum. Kyōsai worked standing over the canvas, drunk on several bottles of sake, and satirical depictions of him in action, stooping brush in hand, circulated in the papers a few days later. The story of the work’s creation was as important as the work itself.

Suppression of the press during the post-1945 Allied occupation meant that manga was hard to come by and many artists created – and consumed – Western styles instead. The artist Tezuka Osamu (1928-89) survived by drawing portraits of US soldiers for money; one client brought him ‘a mountain of American comic books’: ‘It was like the heavens opened and rained manna. There were absolutely no manga materials around at the time. I read through them like a worm, was overjoyed, and copied them obsessively.’ Tezuka is widely regarded as the father of modern manga and his career coincided with manga’s international rise (his early animation work paved the way for anime, manga’s moving image cousin). American influence on his most famous character, Astro Boy, is clear: boxcar eyes, smooth helmet of hair, triumphant raised fist. His borrowings muddied manga’s distinctiveness and it is sometimes hard to see what sets Tezuka’s work apart from other international comic traditions. Scenes from his Princess Knight could easily be from Disney’s Bambi, or French and Belgian bandes dessinées such as Tintin and Astérix. In return, America borrowed freely from Tezuka’s canon, not always with permission: frame-by-frame sequences of The Lion King are taken from Tezuka’s Kimba the White Lion (the theft is the subject of a joke in an episode of The Simpsons: ‘You must avenge my death, Kimba – I mean Simba’).

After the 1951 Treaty of San Francisco that ended the occupation, and the lifting of press censorship, manga production grew rapidly. It peaked in 1995, a year in which 1.34 billion comics were printed. The role of publishing houses in manga’s history is such that they are afforded their own corner of the exhibition – in which video interviews with editors and publishers explain production and marketing techniques. Tezuka said that editors would wait outside his house to collect commissions, some even hiring minders to follow him around the country and seize drawings as soon as he finished them. His close rival, Fukui Ei’ichi, died of karoshi, exhaustion from overwork, in 1954. Towards the end of his career, Tezuka was said to possess qualities equal to those of his most famous characters: undertaking marathon storyboarding sessions over several days without sleep, and dictating plots for one manga to an assistant while drawing panels for another. He is reported to have painted upside down at times, like a bat. This Herculean output was a feature of Japan’s earliest comics too: Hokusai was known by more than thirty different names during his lifetime and created at least thirty thousand works (there are four thousand sketches in the Hokusai Manga series alone). On his deathbed he is supposed to have said: ‘If only heaven will give me just another ten years … just another five more years, then I could become a real painter.’ Tezuka’s last words were: ‘Please, let me work.’

Manga has always had an international appeal. It also has an industry in the mould of Hollywood and a particular facility for distilling and accentuating extremes. It can be cute and kawaii, as in the Pokémon franchise, but also gruesome or otherworldly, as in the Yokai (supernatural) genre, without losing its overall visual consistency. Characters could step between panels, from comic to comic and from book to animation, without disturbing the feel of each work. Lines are inevitably blurred: sweet and sickly, animal and human, child and adult.

It has always seemed to me that manga lends itself best to horror. The absence of colour requires more imaginative scare tactics: penmanship provides the gore. Manga blood is jet black and uncommon; wounds are inscribed with dense and detailed cross-hatched lines. In Itō Junji’s Uzumaki, the coastal city of Kurōzu-cho is plagued by a supernatural curse: its citizens are obsessed with spirals – they long to embody them. The British Museum has an original sketch from the first volume of the series. An elderly resident, Mr Saito, has succumbed to the curse: in the image, his family lift the lid of a shallow barrel to expose his skinny frame contorted into an exaggerated swirl, feet snapped back above his head and hands clasped together in a central twist. He looks like a cinnamon Danish. An otherwise cartoony image is made terrible by its finer details: the intricacy of the shading on Mr Saito’s elongated ribcage; a pair of glasses lying amid the carnage. The panel also highlights the inherent difficulty of displaying comic-book art in a museum. In print the image appears on a full-page spread and, while the previous panels are on display to provide some context, you lose the sense of anticipation, of turning the page as the lid is lifted for the big reveal.

Animation is a natural progression for manga, a final resting place for a style that has chased the cinematic possibilities of line drawing for so long, and it seems appropriate that the exhibition closes with a montage of the work of Studio Ghibli, anime’s most famous production house. Studio Ghibli’s output draws heavily, perhaps more than anything else in the show, on traditional Japanese art. In 2015 the studio animated drawings from the 12th-century Handscrolls of Frolicking Animals as part of an advertising campaign for the energy company Marubeni Power. A small section from the scrolls showing an anthropomorphic rabbit dancing with a frog is reprinted in the exhibition, alongside a video interview with Tezuka in which he calls the Handscrolls the first manga. Studio Ghibli’s films are for children, and have childlike characters, but, as with the kibyōshi comics, the themes are often existential. In Pom Poko (1994), raccoons with shapeshifting testicles fight to save their home from aggressive urbanisation, while Porco Rosso (1992) follows the exploits of an ex-World War One pilot turned bounty hunter, who has been cursed to spend eternity as a pig.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.