Louis-Léopold Boilly’s long life – his career began during the Ancien Régime and lasted until the final years of the July Monarchy – makes it hard not to view his work in parallel with the huge transformations that took place in French society during that period. Born near Lille in 1761, he received no formal training, but his early paintings impressed a local bishop, who arranged for him to work and study in Arras. When he arrived in Paris in 1785, Boilly specialised in cabinet paintings for private collectors. Two Young Women Kissing (c.1790), on display at the National Gallery’s small exhibition of his paintings (until 19 May), was previously catalogued as The Friends and Two Sisters, kidding absolutely nobody. These early works, heavy in innuendo and set in fashionable interiors, are far removed from the crowded Parisian street scenes that later became his stock in trade. Boilly’s concentration on frivolous or licentious topics pandering to the tastes of the Ancien Régime made him the subject of suspicion during the Terror, when he was denounced as a counter-revolutionary by a fellow artist Jean-Baptiste Wicar, and accused of making paintings that ‘dirty the walls of the Republic’. Forced to defend himself before the Société Populaire et Républicaine des Arts, Boilly was exonerated, largely due to his canny submission of a painting representing The Triumph of Marat (1794) and several other revolutionary works. It was lucky he could paint quickly.

Boilly’s career benefited from the Revolution’s transformation of art institutions and the new commercial opportunities this created. In 1791 the biennial Salon exhibitions were democratised, allowing a wide variety of artists to show their work there for the first time. Genre paintings and portraits filled the walls and dominated the art market. Boilly was an astute operator: he offered paintings in different formats – small, medium or large – to match the purse of his middle-class patrons, but he also knew they wanted works that built on the authority of the art historical past, not made a complete break with it. The Meeting of Artists in Isabey’s Studio, on loan from the Louvre, is a manifesto for the new conditions. Made in the looser political climate of the Directory, it was a hit at the Salon of 1798. The painting shows 31 artists, architects and actors, including Boilly himself, who together constituted a new pantheon of French art. ‘The crowd lays siege to this picture,’ one critic wrote, noting with disapproval the fun visitors had identifying those depicted. While the Revolution’s institutional changes had allowed many more women to exhibit, only men are shown in Boilly’s picture. These newly legitimised artists – porcelain painters, flower painters, printmakers, miniaturists, landscapists, military painters – are striving to align themselves with the greats of the past (old masters, including Leonardo and Carracci, are depicted on the frieze in the background), while demonstrating their ease with the demands of the market.

Boilly painted around five thousand portraits – a staggering number. Most of them had the same dimensions – 22 x 17 cm – and he boasted that he could produce one in only two hours. His family were regular sitters and he evidently enjoyed reproducing his own features: his beaky nose and round spectacles recur in multiple works. He also used himself as one of the models for a series of grimaces. His lack of academic training is sometimes evident in the cursory modelling of the body, but his portrait subjects are always identifiable as individuals. Their attributes, too, share this expressive register, rendered with minimal means: a characteristic hat, an umbrella, a necklace.

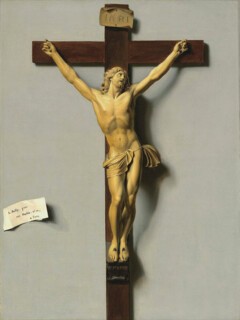

Boilly’s attention to textures and surfaces is remarkable. Fabrics crackle and shimmer. Fishbowls, telescopes and apples catch and reflect light. A bug-eyed child – probably one of Boilly’s sons – sits naked, clutching the floppy ear of a dog; we’re meant to think about the confluence of skin and fur, about touch and vision. Comparing Little Feet (1791) opens the exhibition, while the final piece shows hands and feet nailed to a trompe l’oeil crucifix. Figures grasp, reach, embrace and point. Madame Louis-Julien Gohin, Her Son and Her Stepdaughters (c.1800) shows the family of Marie-Suzanne Gohin, the second wife of a Parisian paint merchant. It’s a long way from the scenes of sons and fathers that populated academic history paintings of the 1780s and 1790s. Madame Gohin’s gaze meets ours directly, but her two daughters, distracted, look off to one side, while her son peers up in the same direction, a box of beetles at his feet. If you look carefully, you can just see a filament extending from his right hand to a tethered insect fluttering against a screen. So that’s what they’re looking at. Note, too, the red, white and blue colour scheme, brought together in the boy’s tricolore shoe and the children’s toys. It’s both a patriotic display and an advertisement for the colours Gohin stocked in his shop: ‘bright, rich carmines of every shade, red lakes, Prussian and Berlin blue’. Boilly knew the details that would appeal to his buyers and took assiduous care over them.

One of the paradoxes of his work is its insistence on the scrupulous depiction of people and objects, while at the same time testing the limits of the means used to represent them. Sometimes verisimilitude threatens to slip into mimicry. Boilly made many grisaille paintings that replicate engravings, complete with ‘printed’ signature and border. The National Gallery’s Girl at a Window (c.1799), often used merely as an example of technical virtuosity, appears in a new light here. The reduced palette provides another way of thinking about vision and materiality. Even his more conventional paintings move across media: Boilly painted on carefully prepared thick white grounds, which give his portraits a luminosity and slickness more typical of panel paintings. His experimentation was driven by commercial as well as artistic imperatives. The boom in new reproductive media created opportunities for artists willing to exploit them. Fascinated with optical devices, which were a regular subject of his paintings (and were possibly used in their production), Boilly was a very early adopter of lithography – in 1845, the year of his death, William Henry Fox Talbot selected one of his prints for photographic reproduction in The Pencil of Nature.

The majority of works on display at the National Gallery come from the collection of Harry Hyams, the property developer responsible for Centre Point, and haven’t been shown before (there’s a nice affinity in the fact that towards the end of his life Boilly abruptly gave up painting to speculate in property). In both subject matter and style they betray the influence of Northern European genre painting, rather than the austere classical models emulated by contemporaries such as David or Ingres. In his crowd paintings Boilly subjects the world of early 19th-century Paris to meticulous scrutiny. An old man lights another’s pipe from his own. A drunk pisses against a wall. Dogs bark and children gape. A pair of hands grip the reins of a carriage, their unseen owner tucked away inside. Figures bustle in the midst of games, greetings, conversation. Boilly traded in fleeting incidents of everyday life, but not in a simply moralistic or documentary spirit. His paintings draw attention to the malleability of the social formations and new urban subjects they represent; the anxieties of the self-fashioning middle class in the wake of the French Revolution.

Perhaps the strangest painting in the exhibition is A Carnival Scene, made in 1832, when Boilly was 71. A diverse group of commedia dell’arte characters ranged on the boulevard Saint-Martin are accompanied by figures in masquerade wearing the outmoded fashions of the Ancien Régime, the bonnets rouges of the Revolution, the styles of the Empire. A dog runs across the foreground, a carnival mask attached to its rear. Is the joke on us, or on Boilly himself? At the centre of the painting one figure – possibly a man in women’s clothing – hitches up their dress to expose their backside to the crowd, teetering precariously above the feathery plume of a soldier’s hat and raised bayonet. Pricking and tickling: that’s a good description of the effect Boilly’s work achieves.

This self-referential quality reaches a crescendo in his trompe l’oeil paintings. Although the practice of making illusionistic works far preceded him, Boilly is credited with the first use of the term ‘trompe l’oeil’: he exhibited a painting under that title at the 1800 Salon. In Boilly’s hands, trompe l’oeil isn’t an artistic dead end, or even a category in its own right, to be distinguished from more serious pursuits. Rather, it’s a continuation of his interest in masks and feints, surfaces and reflections, proliferation and reproduction. After all, we’re not really meant be tricked by the painting but to take pleasure in the intellectual and visual games the artist is playing. Boilly’s commercial acumen is of a piece with this sort of art. His 1812 trompe l’oeil of an ivory and wood crucifix is just about the least religious treatment of the subject one could imagine. Attached to the wall supporting the impressively rendered crucifix is a paper cartellino advertising Boilly’s services and giving his address at 12 rue Meslée, Paris. If you want one, you know exactly where to go.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.