From time to time I’ve had the experience of revisiting a novel only to find that a scene which I thought had made a strong impression on me wasn’t there at all, or only passingly, and that my imagination had done the rest. Pierre Bonnard seems to have painted in this way – as a reader rather than a writer. He didn’t paint from life, but made drawings and noted down colours (he also recorded the weather, though that doesn’t seem to change much in his pictures), using them as prompts when he returned to the studio. Many of his subjects were intimately familiar to him: his companion Marthe, whom he painted again and again, her little dog, their houses at Vernonnet in Normandy and Le Cannet in the south, the view from his studio, from the dining room, of the bathroom, the washstand, the gingham tablecloth, the patterned towel, the white teapot. It’s one of the nice effects of Bonnard’s pictures that these places and things quickly become familiar to the viewer too, so that even in the course of a single exhibition, like the one currently at Tate Modern (until 6 May), we begin to feel that we too are sitting down at the old kitchen table for our morning coffee.

Intimacy (Bonnard and Vuillard were both thought of as intimistes by contemporaries) has a peculiar relationship to memory. Both can be ways of not seeing – the more we get to know an object or a place (or a person) the less we are able to see it clearly – and in his later work Bonnard apparently needed to avoid the subject in order to paint, finding the presence of the ‘motif’ an impediment (‘très gênante’). When he tried using a model after Marthe’s death, he told the woman to pretend he wasn’t there. It might be nearer the mark to think he was pretending that she wasn’t there, which isn’t to say that Bonnard didn’t look – he spent a lot of time just looking. The drawings he painted from are sometimes sketchy and furious, sometimes fussy, but never terribly precise, far from bravura pieces or the sort of detailed studies that artists of the past used to re-create musculature or drapery. Yet it was this sort of visual memory that he must have depended on. Which of us could outline, let alone colour and shade, any room in our house, or even a friend or a lover, entirely from memory?

This singular approach makes Bonnard’s later work both childlike and, given his self-imposed constraints, highly accomplished, lending it in the best instances a charm and inquisitiveness that is not entirely well served by the Tate Modern show, the first major British exhibition of his work in twenty years. The last occasion, in 1998, took in some of Bonnard’s early graphic work – he was an excellent illustrator and printmaker, contributing regularly to La Revue blanche as well as to books – and his commissions for decorative panels and murals. The current show bypasses this stage to begin in 1907 (there is one exception to the chronology) with a purported crisis of confidence that led to his shift away from commercial work and from the Nabis, the Post-Impressionist group of his youth whose allegiance was to Gauguin and Cézanne. Over the following decades he spent less and less time in Paris, partly on account of Marthe’s illnesses and dislike of society. Their relationship seems to have been founded on exclusivity and mistrust. Bonnard met her in 1893, or rather followed her after spotting her in the street. She didn’t tell him her real name or age; he kept their relationship secret from his bourgeois family.

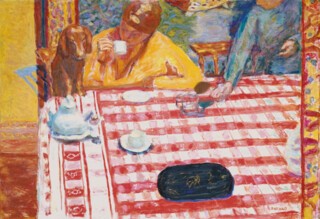

If the viewers of Bonnard’s paintings are being let in on a secret, it’s one that he appears to divulge wholeheartedly. There is generosity – as well as painterly convenience – in the way he tilts the scene upwards so that the paintings seem to tip their contents towards the viewer, always disclosing. Sometimes the effect is stranger than we might realise. In Coffee (1915) the kitchen table takes up two thirds of the scene; the figures at the top of the canvas are so closely cropped that one of them has lost most of her head. What is the subject here? The marvellous red and white chequered tablecloth? The insubstantial snowy white teapot? The dark heavy shape – perhaps a lacquer tray – in the lower half of the picture, which disturbs the stripes of the cloth around it? The woman drinking coffee, with the cup just paused at her lips, and the little dog with his forefeet on the table have the same downcast gaze; their chestnut hair catches the light in just the same slick way. Are they what we should be looking at? Perhaps it is all of these and something more: the shadows that Bonnard paints in bright ultramarine have a life of their own – the one cast by the woman’s chair hovers impossibly behind her, demanding to be an equal part of the picture.

This effect, like the decorative panel that runs down the right of the canvas, insists on the two-dimensionality of the image. Disliking the easel and stretched canvas, Bonnard would hang a large piece of canvas across the main wall of his studio and work on several paintings at once, extending or cropping across the space as he painted. ‘I don’t like to paint in grand rooms,’ he wrote, ‘they intimidate me.’ In paintings like Coffee one has the sense that he wants to show us a little moment, but not make too much of it: pushing the characters to the edge of the picture creates a pleasing off-centredness – something he surely learned from his graphic work and his study of Japanese prints – but it’s also a refusal to give us all the information we might want, to submit to the usual rules of engagement. While in reproduction Bonnard’s paintings lie still and accessible, their colours fixed and flattened, when you are in front of them the canvases seem to swim; his habit of painting everything with equal intensity, equal vividness, means that even shadows and empty spaces are animated and his sometimes too fussy brushwork blurs edges and undermines depth. It’s almost impossible to grasp the paintings, to see them all at once.

This can produce pleasurable effects, like the jangliness of Balcony at Vernonnet (1920), with its wild vegetation. (Monet lived across the river from Bonnard but the two artists’ gardens were very different.) It has also led to Bonnard being written about as one of the foremost painters of perceptual effects. His own letters and notes seem to confirm the idea that he was seeking to capture the first impression –the sense of walking into a new space and being dazzled by it, unable to distinguish its parts properly. One has to scan the picture carefully to make everything out. In some paintings, especially Dining Room in the Country (1913), this stipple and blend of colour brings the whole flickering surface to life. The red of the interior is echoed in the dress of the woman who casually leans through the open window; the tablecloth and door glow with a mother of pearl sheen in the blue-green light of the garden (Bonnard often used waves of pastel paint to create shimmering outlines and surfaces, particularly for flesh). Interior and exterior are one. But in other works at Tate Modern, Landscape at Le Cannet (1928), say, it’s harder to see Bonnard as an artist investigating visual perception than as someone who didn’t quite know what he was doing, or was painting on instinct.

As he grew older Bonnard seems to have cared less and less about anatomy or relations of scale. His earlier work as an illustrator guides his decision-making in places, or perhaps this was just how he liked to paint, with an element of caricature (cartoons, like memory, condense information). He squiggles and draws across his surfaces. His figures are often squat and round-faced, their features obscured or minimised. Hands are blurred or trail off, feet are encased in little shoes (even in many of the nudes), cats and dogs become smaller and smaller – little animal motifs rather than creatures pertaining to reality. In the exhibition the sudden preponderance of this menagerie, popping out from previously familiar paintings, becomes a bit irritating (there is a tiny cat on each of the chairs in Dining Room in the Country and they seem to be conversing). It is an odd mixing of registers, and yet here they are again – little dogs poking their noses into the scene, not so far from Bonnard’s 1904 drawings for Renard’s Histoires naturelles or his lithographs of cavorting terriers (one of the problems of cutting off the early work is that viewers have no sense of this hinterland). The earliest work in the show, Man and Woman (1900), is sometimes read as a scene of shameful post-coital detachment, the woman bathed in shadow and separated from her partner by a large screen, but the mood changes entirely when you catch sight of the two little kittens with which she is playing.

What can seem cute in prints or illustrations (or in letters: Bonnard complains in one that the cat has eaten the cream cheese) is more problematic in a painterly style whose antecedents were not in graphic stylisation but in fidelity to the observable. The attitude might have a different force in Gauguin, with his areas of flat colour and bold line, than it does in Bonnard’s busy surfaces. It seems to limit the paintings, and jars – at times I think embarrassingly – with the underlying darkness or discomfort in many of the works. Bonnard was by all accounts a man with a strong tolerance for discomfort. He and Marthe lived sparsely and he painted in a narrow galley barely fit for a studio, below a mezzanine that he had to climb up to in order to see the entirety of his pictures. In photographs he looks like the civil servant his family wanted him to become: lanky and awkward, with a little thin moustache and little round glasses. Seven of his strange, late self-portraits are on display at Tate Modern, painted between 1930 and 1945. Many of them show him reflected in a mirror, his pose ranging from reticence to futile confrontation to a kind of stillness in the final works, balder, thinner and – without his glasses – unseeing. Sometimes his face is so dark it’s impossible to interpret. Bonnard was a successful artist in his lifetime, turning down honours and retrospectives, but these paintings speak of failure and frustration – the frustration of ageing, perhaps, or of life after his affair with Renée Monchaty, which ended in her suicide in 1925.

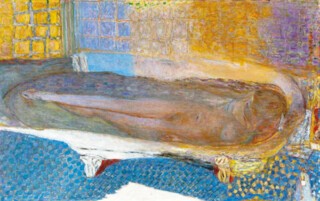

Perhaps it was as much Bonnard’s diffidence and inability to face the subject head-on that led him to shadow and conceal faces; we become very familiar with Marthe’s narrow-hipped, high-breasted body without ever properly seeing her face. Even in his photographs she is often blurred or shaded, shot against the light, and it comes as a shock to see in one archival image that she had quite a big nose. Bonnard was less dependent on photography than many of his contemporaries, but his compositions can have a chancy offhand informality that seems to emulate the snapshot, especially the accidental sort where someone has walked in at the wrong moment (as in Two Women in the Garden and the 1925 Nude in the Bath) or in which a part of the photographer – or painter – protrudes, like the folded knee in Large Blue Nude (1924). Degas said Bonnard ‘cherished the accidental’ and that seems to be part of what makes his pictures so approachable, along with their wobbly lines and bright colours. But it can also give us an uncomfortable proximity to their unwitting subjects – Bonnard’s people rarely look us in the eye – or put us in a voyeuristic position: in many of the famous paintings of Marthe bathing the viewer looms over her head, as Bonnard himself must have done.

Five of the bath paintings are on display at Tate, though not all in the same room. Marthe took long baths for her ailments and Bonnard returned to the subject of the bather repeatedly between 1925 and 1946. The final two paintings were created after Marthe’s death, and even the first, begun when she was in her fifties, shows a young woman (some have taken against this portrayal, but it could be interpreted as one of the peculiarities of memory: that after a certain point we forget we have aged and remember others as more youthful than they are, even as they were when we first knew them). The baignoires display Bonnard’s work with colour and pattern at its most playful and most pure. Light came into the bathroom at Le Cannet from two windows, bouncing off the wall behind Marthe as well as illuminating her from the far end of the room. In each painting the bath takes on a different shape, swelling and narrowing, encompassing and tapering, to fit Marthe’s form and contain her like a tomb. In Nude in the Bath, from 1936, the floor is a spangle of yellow and turquoise, the bath an oyster’s shell, a shallow dish offering the bather up to us. Although in other bath paintings Marthe’s body appears corpse-like (the eerie appearance of flesh seen below water), the most jubilant of them have the sense of everything being underwater, or dissolving into vapour. The chromatic field has a warp and weft of its own, and one thinks of what Bonnard could have achieved with Vuillard’s use of pattern to structure a scene, if he’d wished.

These effects of shimmer and dazzle, which owe something to the colourful sweet wrappers Bonnard pinned up in his studio, sway and dart across the painting, like shoals of little fish, or as Patrick Heron put it in another watery simile, ‘like a piece of largescale fishnet drawn over the surface of the canvas’. Bonnard is loved by many painters, and by writers who paint, and there has been much excellent writing on him (Timothy Hyman’s Bonnard especially). His indeterminacy is frequently described in literary terms, though it’s clearly not the same thing as Henry James’s metaphorising around a subject, or Mallarmé’s deliberate evasions. Artful uncertainty is a different category from uncertainty proper (Bonnard was famous for retouching his work long after completion, not like Turner on varnishing day or Balzac’s Frenhofer making the final flourish, but continually changing his mind or adding newly discovered colours). Bonnard’s singular pursuit of honesty – he claimed to distrust virtuosity – might mean we have to read him differently from Vermeer, say, or even Matisse, whose pictures want to achieve a formal unity. Yet he can’t be considered straightforwardly naive. Bonnard asks us to indulge an anti-virtuosity that is nonetheless bound up in traditions of virtuosity; his paintings don’t depart so entirely from the conventional register that they can be considered ‘outsider art’, or even particularly original, and he had less interest in tribal art than nearly all his contemporaries.

Where then to place him? Picasso’s frustration – ‘that’s not painting, what he does … painting isn’t a question of sensibility’ – is understandable. Painting is active and we prize well-executed intent and inventiveness, not avoidance and haphazardness. The places where Bonnard is most exciting, as for instance when he plays with depth by allowing the pattern on the floor to overlay part of the figure standing on it, are never distinguished in his pictures from areas of doubt and predictability. Phantasmic, indecipherable zones appear in some of his scenes, like the amorphous white shape in Nude at Her Bath (1931), and signify a failure of memory, or a failure to surmount it artistically, or perhaps a grasping towards abstraction without the will to see it through. Placing as much faith in memory as Bonnard seems to have done (the ability of memory to retain fleeting impressions) can’t have been the best way to capture the sort of detail he liked, the newness or formlessness of things, even the effects of light. The conjuring trick doesn’t always come off. But perhaps we are asking too much of him. Bonnard used to be thought of as the painter of happiness, of unspoiled afternoons in the country, of open windows and dappled reveries in quiet houses. The interrogator of perception who has replaced him is intriguing, if not wholly convincing, as is the darkly psychological painter; the clumsy, uncertain colourist less so. It seems a shame to lose the idea of his paintings as romantic submarine daydreams. Bonnard ought to exist for the same reason that we enjoy anything pretty, bloomful, billowy, patterned, pink – even his name, bonheur, bonne heure, wants to make itself decorative.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.