In 1789, a year famous for a number of other reasons, the Swiss scientist and alpinist Horace Bénédict de Saussure invented the cyanometer, an instrument that measures the blueness of the sky. This simple paper colour-wheel had 53 sections, ranging from white to deep blue. Saussure tested the cyanometer at different elevations in Switzerland, hypothesising that the sky gets bluer the higher you climb, as the water vapour thins to unveil heaven’s darker nature. His highest reading was 39 on the scale. The Prussian scientist Alexander von Humboldt, who carried the instrument with him on his travels, took a reading of 46 during his ascent of Mount Chimborazo in the Andes in 1802.

Humboldt was born in 1769. His scientific activities would be impossible to confine within modern disciplinary boundaries: he worked in geology, botany, geography, ethnography, meteorology – the list goes on. The labels and labelling might have puzzled him. He wanted to explain the entire universe. He would give the title Cosmos to his masterwork – published, as he said, ‘in the late evening of a varied and active life’. Cosmos appeared in five volumes between 1845 and 1862, the fifth and final one after his death in 1859. By then, Humboldt was said to be second in fame only to Napoleon Bonaparte.

For this new edition of his works, Andrea Wulf has condensed the work of one of the most prolific non-fiction writers of the early 19th century into 792 pages of text – the only one-volume selection in English. On the dustjacket, a detail from a portrait of 1843 shows Humboldt holding a manuscript of Cosmos and sitting beside a library globe, with the Americas rotated towards him and at an angle to the viewer. It’s an efficient summary of the man, emphasising the significance of the Americas to him, and to his final, major accomplishment.

Scientific expeditions proliferated during Humboldt’s lifetime: they aimed at assessing territory for European empires, as well as collecting specimens and artefacts for museums, and theories for savants. Humboldt was a newborn when Captain Cook arrived at Tahiti in 1769 with a group that planned to observe the transit of Venus across the face of the sun. (The event offered an opportunity to calculate the ‘astronomical unit’, the distance between the earth and the sun, still used for measurements within the solar system.) Humboldt was seventy when Darwin published his Journal and Remarks (1839) about his voyage on HMS Beagle, the basis for his hypothesis about evolution by natural selection. Humboldt himself had set out in 1799, at 29, to make a five-year circuit of the Spanish colonies in the Americas, covering six thousand miles by land and sea. Like Tocqueville and Meriwether Lewis, he travelled with a sidekick, the French botanist Aimé Bonpland. The friendship was close and their correspondence affectionate; there has since been speculation that they were lovers. They were certainly steadfast friends and colleagues. Humboldt insisted that Bonpland be credited as co-author on the stunningly influential Essay on the Geography of Plants (1807).

Humboldt’s works were mainly descriptive, containing details of interest to specialists, but not meant only for them. Personal Narrative of Travels to the Equinoctial Regions of the New Continent (1814-29) is especially full of sight and sound, to the point of sensory overload. We see with him the blues of many skies, an alley of avocado trees leading to a monastery, the precise appearances of different kinds of monkey (‘The closer they resemble man the sadder monkeys look’). He describes the tremble of earthquakes in Venezuela and the nervous business of handling electric eels without getting too badly zapped, and records an invitation to test the hypothesis that certain bees sting only if you pick them up by their legs: ‘I did not try.’ He hears the cry of a jaguar that has probably just eaten the expedition’s favourite dog, listens to a shrub ‘whose large, leathery leaves rustle like parchment’, hears the snorts of freshwater dolphins in the Orinoco River, and compares the twangs of guitar strings made from howler-monkey guts to those made from boa-constrictor guts. He even captures the sound of silence: a tangle of salamanders, geckos and iguanas rest with their mouths open, noiselessly panting in ‘the hot air with delight’. He tastes manatee and curare. The latter’s ability to kill prey is judged by its bitterness, but it is harmless if ingested (it has to reach the bloodstream through a wound to have an effect), so Humboldt tries some when his Indian hosts brew it up. He comments on many smells, from the fragrant sap of the curucay, to Brazil-nut oil, which has a tendency towards rancidness.

In Venezuela, he delighted in conversation with the local gentry, men and women, everyone smoking cigars in moonlight on a riverbank. ‘We lived like the rich,’ he said of one rural idyll. ‘We bathed twice a day, slept three times and ate three meals in 24 hours.’ It wasn’t always so pleasant. The expedition’s boat nearly capsized in the middle of the Orinoco River. Humboldt managed to save his diary, even as ‘books, dried plants and papers’ slid overboard and began to float away. The men got the boat back on course and retrieved much of what had gone overboard. ‘As night fell,’ he wrote, ‘we camped on a deserted island in the middle of the river. We dined in the moonlight sitting on scattered empty turtle shells. How pleasing it was to be safe and together!’ Robinson Crusoe’s fate, to be a lost man on a deserted island, was not part of his plan.

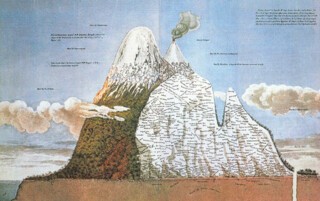

His great contribution to science was synthesis. ‘Rather than discovering new, isolated facts,’ he explained in his Personal Narrative, ‘I preferred linking already known ones together.’ Later, in his Essay on the Geography of Plants, he declared his goal more fully: ‘I bring together all the physical phenomena that one can observe both on the surface of the earth and in the surrounding atmosphere.’ Humboldt interpreted the earth, in modern scientific terms, as a total system. He centred his claim on the role of plant life. Plants depend on their geographical and geological position, he reasoned, and then all animal life depends on the vegetable. In working out the connections between physical place and plant life, Humboldt thought about the effects of altitude. European geography had long taught that living forms varied according to latitude, meaning exposure to the sun. Anyone living near mountains would have known that vegetation also varied by altitude. Humboldt made that variation a central principle of geography, and of the science of living organisms: ‘The observer who leaves the centre of the earth by an infinitely small amount compared to the radius can reach a new world, so to speak,’ far more than ‘if he were to pass from one latitude to another’.

Today, Humboldt seems unusually prescient because of his thoughts on climate. A justly famous illustration from the Geography of Plants, showing Mount Chimborazo in cross-section, is reproduced in this edition. It’s a brilliant infographic, a visual summary of what Humboldt had observed and what he had learned from others (Europeans, Creole Spanish settlers and indigenous peoples), offering a stratigraphical assessment of the relationship between altitude, vegetation, precipitation and topography. Climate was affected by both latitude and altitude, plus the atmosphere (including humidity and temperature) generated by those conditions and the vegetation that resulted. If the atmospheric conditions changed, so must the living beings: ‘If the temperature of the planet underwent significant … changes, if the proportions of land to sea and even the height of the atmosphere and its pressure have not always been the same, then the size and shape of the organism may likewise have been subject to manifold changes.’ Cosmos analyses the features of the natural world, the relationships between them, and the power of human perception to appreciate them, whether in science or art or religion.

Humans also had the capacity to destroy the natural world. In three swift paragraphs, describing the area around Lake Valencia in Venezuela, Humboldt explained that each new settler’s hut lowered the water line, because the hut-dwellers cleared and drained land for cultivation. A doleful cause and effect could be seen from the Alps to the Andes. ‘By felling trees that cover the tops and sides of mountains men everywhere have ensured two calamities at the same time for the future: lack of fuel, and scarcity of water.’ Humboldt worried deeply about ‘mankind’s mischief’. In a diary entry from 1801, he predicted that any humans who ventured into outer space would probably take with them the tendency to leave everything ‘barren’ and ‘ravaged’.

Widely read in his lifetime, Humboldt remained famous for at least a generation after his death. His contemporaries Goethe and Darwin admired him; so would Thoreau and John Muir. Many places and things in the natural world now bear his name: a current in the Pacific Ocean, towns in Kansas, Nebraska and Saskatchewan, a county in California, a university in Berlin, not to mention a penguin, a bat, a cactus, an orchid, a mushroom and a big, big squid. There isn’t any escape from him off-planet, what with the Mare Humboldtianum on the moon. The list of Humboldtiana is odd in a way, given their namesake’s goal not to be a discoverer of things. It would perhaps have been a bit extravagant to have renamed the entire planet after him, but certainly his science prefigured the Gaia hypothesis, Spaceship Earth, the Whole Earth – theories that present the planet as a single, living entity.

Humboldt’s vision of life on earth has not been refuted, though its details have been updated (and its equipment – no more paper cyanometers). Environmental science is neither thrillingly new nor hypothetical. Controversy about climate science has been manufactured, mostly for the convenience of fossil fuel interests, but also to suit people who see the implications of climate science as a revolutionary attack on their way of life. Humboldt himself did support some revolutionary changes. He was a consistent critic of slavery at a time when this was far from typical among privileged white men. He was outraged by public sales of slaves in Venezuela – his first sight of the market in human labour in the Americas – and called slavery ‘institutionalised barbarity’ and ‘possibly the greatest evil ever to have afflicted humanity’. When a translation of his Political Essay on the Island of Cuba appeared in the US in 1856 with the denunciations of slavery expurgated, Humboldt issued a press release to be published in American newspapers, repudiating the edition and stating that the deleted passages were the most important in the book. He forfeited political contacts and influence as a result of his support for the failed revolutions of 1848.

And yet some problems remained invisible to him, and some solutions seemed excessive. His awareness of ‘mankind’s mischief’ notwithstanding, he underestimated the human tendency to ravage nature. The American wildernesses seemed to him unassailable. He wrote of one part of the American tropics that it ‘still seems wild … we cannot doubt that, even with an increasing population, the torrid zone will keep its majesty of plant life.’ If only. His optimism is particularly striking in his remarks on the Columbian exchange: the swapping of biota between hemispheres that brought smallpox and ruminants into the New World and sent back tobacco and potatoes. The scale of the exchange was already prodigious in Humboldt’s era. The hinterland beyond Caracas, he noted, was estimated to have nearly two million domesticated oxen, horses and mules; and there were 12 million cattle and three million horses on the Buenos Aires pampas, ‘not counting the animals without owners’. These figures don’t quite support his claim that wilderness would withstand settler invasion. Nor did he acknowledge the catastrophic decline in the indigenous population. He remarked that the native population in Mexico was growing quite vigorously, despite its earlier collapse after Spanish conquest. That recovery showed, he felt, ‘how mistaken it is to assume the destruction and diminution of Indians in the Spanish colonies’. ‘There are still more than six million copper-coloured races in both Americas,’ he insisted, ‘and though countless tribes and languages have died out it is beyond discussion that within the Tropics, where civilisation arrived with Columbus, the number of Indians has considerably increased.’

He truly believed civilisation had arrived with Columbus. In the Americas, he said, ‘civilisation slowly works its way inland from the coast,’ carried by Europeans to the uncivil Indians. His offhand contempt for many Indians is painful to read (he described Carib villages as having ‘fat, disgustingly dirty women’), but he depended on them for information, labour and guidance during his travels. He never considered them intelligent partners in science, though he was quick to regard them as potential specimens, particularly for phrenology. When he visited a cavern where Indians buried their dead in large baskets called mapires, he and Bonpland ignored ‘the indignation of our guides [and] opened various mapires to study the skulls’. They packed up some of the remains, intending to deposit them in European collections, again in spite of their guides’ protests. He saw little reason for Indians to resent Spanish rule and, except for slavery, didn’t support any radical change to the colonial societies he visited. When the political revolutions associated with Simón Bolívar broke out after 1811, he worried that without strong ties to Spain the educated elite in colonial societies would be too small to foster the civilised society he prized. Political independence was not, as he saw it, a valid goal, particularly in places where non-Europeans were likely to outnumber creole whites.

If there is a purpose in dwelling on Humboldt’s errors today, it is to recognise that we persist in some of them, in particular the inability to see humanity’s dependence on nature. Humboldt defined nature in terms of interconnections, but – as a seeker of blue skies and happy endings – he also underplayed the damage humans would do to the natural world, damage we still underestimate, to our peril.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.