There is no reliable single view of a big city building. Take London’s tallest skyscraper, the Shard. Here’s one view: it looks like a blown-up version in glass and steel of Kim Il-sung’s Tower of the Juche Idea in Pyongyang – except it’s a monument to capital rather than revolutionary self-reliance. Both towers are steep pyramids, stretched vertically until they reach insane heights above the river they stand beside, with a viewing platform at the top drawing tourists from all quarters to see the low-rise city from an impossible angle. In place of the 25,500 stone blocks of Kim’s tower – one for every day of the first seventy years of his life – the Shard is encased in 11,000 high-tech low-iron glass panels: if we’re into decoding buildings, could this be one for each of the 11,000 military personnel at the US’s largest base in the Middle East, in Qatar, whose oil and gas money supplied most of the half a billion pounds required to build it?

The Shard is a thousand feet tall, standing on a slab poured from seven hundred truckloads of concrete. The tenants on some of the lower of its 95 storeys include Tiffany & Co, Campari, the Al Jazeera Media Network, the gambling company Tabcorp, South Hook Gas, the asset manager Foresight and the corporate consultancy firms Duff & Phelps and Protiviti (‘Face the Future with Confidence™’). Above them are the 19 storeys of a Shangri-La hotel, with its lounges and bars and restaurants and conference rooms and infinity pool, the highest in Western Europe.* Above this, occupying 13 storeys, are ten super-luxe apartments that were expected to sell for up to £50 million each and which six years later are still empty: they’ve never officially been marketed, either because nobody with that kind of money wants to live south of the river, or because they’ve been reserved for younger members of the Qatari royal family to retire to. Whatever the reason, their obscene opulence is its own monument to capital accumulation, their expensive emptiness a sky-high reflection of a problem that plagues the city below.

But look from another point of view: the tallest building in London is merely the 96th tallest in the world. If you fancy a dip in a pool in the clouds, go to Singapore and try the one in the SkyPark on top of Marina Bay Sands – three times Olympic length. If you’re into big-money building projects, check out the new European Central Bank in Frankfurt (cost: £1.2 billion), Apple’s new headquarters in Cupertino (£3.8 billion), or – if you really want to revel – the ongoing development at the Masjid al-Haram in Mecca, which is said to have cost the Saudi government around £80 billion so far. If you want sheer height, see Prince Al-Waleed bin Talal’s skyscraper currently going up in Jeddah, which will be taller than three Shards balanced on top of one another. For megaproject collectors, the Shard is a zero; for many of the hundred thousand or so people who pass underground through London Bridge Station every day, the tower above them is something they’re barely aware of, if they even remember it exists.

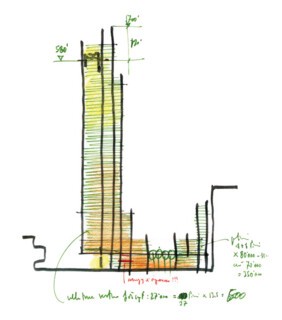

It’s hard to be in London, though, without at some point at least noticing the Shard. From a certain perspective it’s there, in the corner of your eye, wherever you look – and up close it’s inevitable. You live with the buildings that give you direction and a sense of scale. From another perspective altogether, you start to think about the person who dreamed it up: the architect, Renzo Piano, who with a green felt tip on a napkin over lunch in Berlin sketched out what a newcomer to the London skyline might look like. He thought of masts and spires and all the things that lived along the Thames; the early drawings show experiments with a more sail-like structure, a right-angled pyramid, dynamically spiralling upwards but tethered to the urban surface. You can still see this conceptual Shard in the building there today, with its deconstructed summit a refraction of Hawksmoor, and making it look as though the tower is still endlessly in process, unfinished, still climbing. And of course when you look again you see that it isn’t a regular pyramid at all, but a complex, multifaceted object that plays tricks with the light.

You get a sense of what it must be like to live in Piano’s mind from the show at the Royal Academy (until 20 January), which presents 16 projects from all stages of his fifty-year career, with the help of sketches, drawings, letters of commission, photographs and maquettes. A film by Thomas Riedelsheimer has him talking: if you take the cynic’s view of big-name architecture and like to do the sums relating to clients and money and cement, I challenge you not to be beguiled by this genial Genoan, twinkling with ideas and firmly rooted in the place where he started. He speaks of Genoa, and the harbour, the boats he began building as a boy: every Sunday they would go to Mass, then visit the harbour, then have lunch. He watched the ships: sailing from China, going to America. ‘So in the mind of a little boy the harbour is the great place of adventure,’ he says. ‘The ships are like buildings in a town, except that they move around. That’s probably the reason my buildings are always flying vessels.’ In Genoa, a city cut into rock with its mind on the sea, he must have found his twin interests in lightness and weight, and a sense that the world was only just over the horizon.

He also found an interest in the properties of materials: his father was a builder. It is hard structural science that enables a roof canopy – ten thousand square metres of ferrocement, just ten centimetres thick at the edges – to float above the new Stavros Niarchos Foundation Cultural Centre on the outskirts of Athens. Piano calls it a victory over gravity. You would think that putting up a €600 million megastructure in austerity Greece might be an error, but thanks to the benificence of Niarchos – a shipping magnate – the building is now in full swing, having taken in the national opera and the one million books, papers and manuscript codices of the National Library of Greece. Piano’s affinity with the artisanal is visible in the wooden models he has made of critical units that will be repeated in his constructions – like the ceiling ‘leaves’ used to diffuse natural light in the Menil Collection in Houston – but also in a drawing he made at the very beginning of his career, for a sulphur extraction plant, in which the workers appear as little action figures in Arte Povera-type smocks.

Renzo Piano Building Workshop, as his practice is called, is still based near Genoa, with further offices on Broome Steet in SoHo and on the rue des Archives in the Marais – in the shadow of the Centre Pompidou, which he designed with Richard Rogers in the early 1970s. At RPBW Genoa, on the coast just to the west of the city, meetings happen at a round table, with no notes taken: bad ideas are encouraged, because they’ll immediately be replaced by better ones as the collective musters its expertise. ‘I don’t see a lot of difference between the office and the rest of the family,’ Piano says – some of his colleagues have been with him for forty years. He’s proud of the fact that there’s no road to the office door: a three-minute ride in a funicular car takes you up the hill, giving you just enough time to catch your breath, take in the view and stop thinking too fast. Visitors to the studio are sometimes shown a shard of glass from the actual Shard, and for me there’s something telling in this memento: it is both metaphor, Shard-shaped, and synecdoche, a piece of the thing itself. Piano is unusual in finding both equally important. A building may be like a ship, as a visual and emotional metaphor, but a building next to the water can also carry over elements directly from the shipyards – like the new Whitney Museum on the Hudson, with its haphazard piles of container-like structures. Piano’s terminal at Kansai International Airport, on an artificial island off Osaka, is shaped like a long-winged glider when viewed in plan; grasp it in three dimensions and you realise it is tapered like an aerofoil.

As Luis Fernández-Galiano points out in the RA’s catalogue, Piano is known for his green felt tip but the most striking colour in his drawings is the orange you sometimes also see, which represents where the busiest zones of human activity may be – as on the lower floors of the New York Times Building, which Piano arranged so as to have the staircases touching the glass façade, in order that the full motion of the hive can be seen from the street. For all his formalism, Piano is interested in the places where people meet – in lobbies and atria, piazzas and courtyards. In Riedelsheimer’s film he talks of the value of ‘urbanity’ – diversity, encounters, all the rest – and says: ‘I see Europe like a big city. It’s a city with lakes, with forests, with mountains, with sea.’ What’s strange and unfathomable in his thinking is that his buildings – or the idea of his buildings – meet in his mind too. For him, it’s clear, his projects – all so different – are connected: like the little boy in Genoa harbour, this eighty-year-old can imaginatively be anywhere, teleported at an instant to wherever he has ever landed, from Rome to Basel to Berlin to Oslo to Cologne to Chicago to Tokyo to Boston to Valencia to Sydney to Dallas to Milan. For the Royal Academy show, RPBW Paris has constructed a model, at 1:1000 scale, of more than a hundred Piano buildings all laid out on a fictional island, complete with trees, roads and hills: in the south, the Kansai terminal; in the north, the Ushibuka Bridge. A central axis or main highway links the Shard to London’s Central St Giles to the Centre Pompidou to the New York Times Building to the Lingotto Factory in Turin. It’s a metropolitan island of the imagination on which I would rather like to live.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.