The earliest fragments of the English language are likely to be a group of runic inscriptions on three fifth-century cremation urns from Spong Hill in Norfolk. The inscriptions simply read alu, which probably means ‘ale’. Perhaps the early speakers of Old English longed for ale in death as well as life. But, as the British Library’s exhibition Anglo-Saxon Kingdoms (until 19 February) displays, the inhabitants of early medieval Britain did more than yearn for ale. The first piece on show is a dark earthenware lid from another Spong Hill cremation urn. It shows a seated man, his elbows resting on his knees, his chin held in his hands. He appears pensive – his pose is not dissimilar from Rodin’s Penseur, except he looks outwards. Indeed, looking outwards is a theme of the exhibition. We might think of Anglo-Saxon England as an outpost at the edge of the known world, but it was connected to the world beyond its shores through a lively exchange of books, goods and ideas.

Visitors are greeted by the Sutton Hoo belt buckle, discovered in a spectacular seventh-century ship burial in East Anglia in 1939. The buckle is Anglo-Saxon bling at its best: from a distance, what you see is a massive lump of gold (it weighs nearly half a kilo). Wearing it on a belt would have been an outlandish display of wealth, power and pelvic heft. Yet, up close, what comes into view is a maze-like pattern of zoomorphic interlace. Snakes, birds and worm-limbed beasts writhe in gold niello. The interlocking bodies are hard to distinguish until you get close enough to follow the gold-stamp patterns that reveal distinct creatures. This was clearly an object made by a culture that valued complexity, one that invited repeated examination of its artefacts and ruminative readings of its texts. The initially unreadable forms of the Sutton Hoo belt buckle are of a piece with the famous Old English riddles of the tenth-century Exeter Book (also on show), or the less well-known Latin Enigmata (‘Riddles’) of Aldhelm, abbot of Malmesbury (d. 709), which require careful consideration to solve.

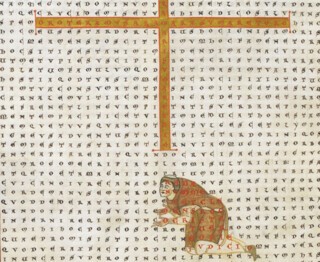

A similar complexity is in evidence in a tenth-century manuscript of De laudibus sanctae crucis (‘In Praise of the Holy Cross’) by Hrabanus Maurus (780-856). The manuscript contains 28 grid poems, which you might mistake for word puzzles. On the folio displayed in the exhibition, 1505 letters appear, arranged in 35 columns and 43 rows. The letters spell out a poem, but also conceal phrases revealed by superimposed shapes and images. At the centre of the grid is a golden cross on which appears a palindromic acrostic, ‘ORO TE RAMUS ARAM ARA SUMAR ET ORO’ – ‘I pray, O cross and altar, to be saved through you.’ The letter ‘M’ forms the central point of the cross, the hinge on which the phrase repeats itself vertically. Beneath this is an image of the author, his eyes lifted in supplication to the glittering cross above him.

I thought of the planning that would have been involved in making this piece of word-craft, at once so clever and so beautiful. This, and the way the grid poem revels in its layers of meaning, felt akin to the scabbard slider discovered at Sutton Hoo. The slider is cloisonné work, in which garnets are set in a gold waffle-shaped base. Beneath each garnet are hatched gold foils. The effect is not very different from that of cats’ eyes at the centre of a road: light is reflected back from the depths of the gems. To find so many garnets – probably mined in India or Sri Lanka – of such a uniform colour and so finely cut seems almost absurd: both an extraordinary display of craftsmanship, and evidence of the international reach of Anglo-Saxon England.

The star of the show is the Codex Amiatinus, made in the early eighth century at the monastery of Wearmouth-Jarrow in modern day Sunderland. The manuscript is a single-volume Bible, a beast made from many beasts: its spine is half a metre tall, it weighs 34 kg and has 1030 leaves, from 515 calfskins. We can only wonder at the investment of time and resources necessary for its production. In the exhibition it is displayed in a glass-fronted case, so that it can be seen almost in its entirety. I had the sensation of looking into the tank of some kind of great, aged turtle.

In 716, Ceolfrith, abbot of Wearmouth-Jarrow, set off from Northumbria bound for Rome, taking the Codex Amiatinus with him. The anonymous Life of Ceolfrith describes how the monks sang and wept as his boat set sail on the River Wear. The book was intended as a gift for the shrine of St Peter, but it never made it. Ceolfrith died en route and the Bible ended up in the monastery of Monte Amiata in Tuscany (hence its name). Ceolfrith’s abbey was a centre of learning (it was home to Bede) and its scriptorium produced works of great quality. The inky sweeps of the Bible’s script are crisp and clear and its illumination sophisticated. Until the 19th century it was thought that the manuscript could not have been made in England, an assumption bolstered by some dedicatory verses which explained that it was a gift from ‘Petrus Langobardorum’, ‘Peter of the Lombards’, to ‘Cenobium Saluatoris’, ‘the monastery of the Saviour’. But, as the Italian scholar Giovanni Battista de Rossi noted in 1888, these words are later additions. Some wily person had sought to claim the Bible for Italy. According to the Life of Ceolfrith, the words should have said that the book was a gift for the shrine of St Peter from ‘Ceolfridus, Anglorum extimis de finibus abbas’ (‘Ceolfrith, abbot from the far-away lands of the Angles’). For the exhibition, the manuscript has returned to the far-away lands of the Angles for the first time in 1300 years.

The Life of Ceolfrith also tells us that the abbot originally commissioned three of these giant single-volume Bibles (known as ‘pandects’). One is lost and the third survives in three sad fragments: a few leaves were discovered being used to wrap legal documents in the 16th century, others came to light in a shop in Newcastle in 1882, and a third fragment turned up among estate papers in Kingston Lacy in 1982. One of these fragments is displayed alongside the monumental Bible, a reminder of the fate it might have suffered.

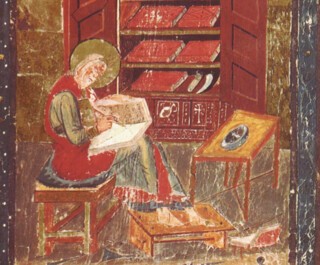

The opening of the Codex Amiatinus on display in the exhibition shows an image of a scribe. He appears with a book resting on his knees and his feet resting on a footstool. Around him are the accessories of his work – an inkwell, a compass – and behind him is a cupboard with angled shelves on which rest nine manuscripts, lying flat with their spines in a horizontal position, rather than standing in a row, as was customary in the Middle Ages. Each manuscript has a dark red binding. The image is apposite because to the left of the Codex Amiatinus display case at the BL is a manuscript in a dark red binding. Like the Codex Amiatinus, it was made in the scriptorium of Wearmouth-Jarrow. You could almost miss it next to its hefty cousin. It is only 13.7 cm x 9.5 cm and it weighs a mere 162 g. But its tiny size betrays nothing of its status as a cultural monolith. This manuscript – the Cuthbert Gospel – is the earliest intact European book. It is still in its original early eighth-century binding – its survival over the centuries is a near miracle. From the early eighth century until 1104 it was hidden inside the coffin of St Cuthbert, during which time Viking incursions destroyed many important libraries in the North of England. Sitting alongside the fragments of one of Ceolfrith’s lost pandects, it is a powerful reminder of how precious the remains of the early medieval past are.

In tiny details the Cuthbert Gospel, like the Codex Amiatinus, tells a story of Anglo-Saxon England’s connections to the wider world. It was copied from an exemplar that came from Italy, though the spacing of its words shows the influence of Irish scribal practice. It is bound in the Coptic style, using a chainstitch method, while its binding design incorporates a vine and chalice motif found in Eastern Mediterranean art – a similar design appears on the fifth or sixth-century doors of the church of Sitt Barbara in Cairo. In stitches, spaces and leather tooling, the Cuthbert Gospel shows itself to be the product of an international elite.

These manuscripts – pinnacles of their art – illuminate the intellectual sophistication of Anglo-Saxon England; other artefacts in the exhibition reveal a delicious, prosaic reality. The 11th-century Ely Farming Memoranda – made up of three slivers of parchment rescued from later bindings – describe the rental of a fen for 26,275 eels. In this fragmentary document scraps of everyday life surface. We hear about ‘þære heorde þe/alfƿold heold æt hæðfelda’ (‘the herd that Alfwold watched over at Hatfield’), which contained 13 sows and 83 young swine. Elsewhere the value of the land is quantified in boats, watercourses, workers, slaves, oxana (‘oxen’), sceapa (‘sheep’), gata (‘goats’), cealfra (‘cheeses’) and flicca (‘flitches’ of bacon). Also on show is the will of Wynflæd, a wealthy woman who lived in south-west England in the tenth century. It describes the manumission of slaves, a bequest of bed linen, books, bracelets, cups and a ‘twilibrocenan cyrtel’, which some have translated as a ‘badger-trimmed robe’. Wynflæd kept slaves and might have worn badger fur – in this she and I are worlds apart, but her care for her sheets, drinking vessels and books feels familiar.

Riddle 47 of the Exeter Book describes how a ‘moððe word fræt’ (‘a moth ate words’). This stælgiest (literally ‘stealing-guest’, or ‘pilferer’) was a ‘þeof in þystro’ (‘thief in the darkness’), who ‘ne wæs/wihte þe gleawra þe he þam wordum swealg’ (‘was not a whit wiser for the words he swallowed’). The solution is the bookworm, but it’s also a meditation on impermanence, and a reminder of how many texts and artefacts from the period have been destroyed by fire, flood, or invertebrate stælgiestas.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.