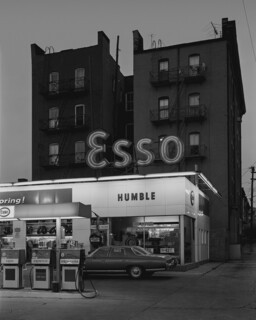

I find this image ravishing, as others might find a Vermeer or Velázquez, although it’s only a cheap copy of a 1972 platinum print, Esso Station and Tenement House, Hoboken, New Jersey (the photograph can be seen in George Tice: A Celebration, at the Nailya Alexander Gallery in New York until 13 October). In the foreground is an Esso gas station, a Ford Fairlane parked behind the pumps, filling up, a fluorescent logo above the white office area, the entire station floodlit, probably with mercury vapour lamps. Behind it, half-hidden in the shadows of early morning or evening, is a four-storey tenement, probably built in the early part of the last century, and indistinguishable from the building my maternal grandparents lived in, just a mile or two down the road.

George Tice, above all else, is a photographer of place: seaside Maine, the Yorkshire moors, Pennsylvania Amish country, or small-town Middle America, portraying the lit interior of Locust Antiques, Locust, New Jersey or Houses along Broadway, Hannibal, Missouri or the faded and layered signage against a brick background of Pentimento, Galena Avenue, Dixon, Illinois, the front of the ‘Lewis’ Restaurant, Main Street, Fairmount, Indiana or the Lincoln Triplex Cinema, North Arlington, New Jersey.

The light is very particular in these small-town landscapes, gathered in the book Hometowns. The book is his favourite format and he has published many: Paterson, Lincoln, Hometowns, Seacoast Maine, Stone Walls, Grey Skies: A Vision of Yorkshire, Fields of Peace: A Pennsylvania German Album, Urban Landscapes. In many of these land and sky take precedence over the built landscape of the photographs of Tice’s native New Jersey. A sense of quietude pervades the images. Although the Midwestern small-town photographs display many of the elements Tice is fascinated by in urban landscapes – shop fronts, hotel façades, empty public spaces, brick façades, street scenes empty of human forms – these photographs of Fairmount, Indiana; Dixon, Illinois; and Hannibal, Missouri present us with another America, of main streets, front yards, soft, riverine light: home to James Dean, Ronald Reagan and Mark Twain, three utterly dissimilar characters but emblematic for Tice of a certain idea of America.

The images in Lincoln at first seem something else entirely. In fact, through these photographs of memorials of Abraham Lincoln in statuary and signage across the Midwest and Northeast, in cities and small towns, Tice is making a different sort of portrait of America. From the solemn, marmoreal repose of statues to the Newark motel bearing Lincoln’s name and image, Tice’s camera pans across the culture, sometimes inflected through the lens of a sociologist, sometimes an anthropologist or student of urban design, sometimes a homespun surrealist.

But the place with which he is most familiar and understands best is New Jersey’s densely populated, industrial north-east corridor, from Middlesex and Union north to Hudson and Passaic Counties. His black and white urban landscapes are shot for the most part on a bulky, old-fashioned, large format 8 x 10 inch Deardorff view camera. Regarded as one of the master dark-room printers of his generation (Edward Steichen gave Tice responsibility for printing his remaining negatives in the final year of his life), Tice’s prints have a particular luminosity and clarity of detail that he seems to achieve through his use of silver gelatin and platinum emulsions.

The sorts of place that attract Tice’s restless eye are Hoboken; Newark, where he was born on 13 October 1938; Paterson (the subject of two book-length collections); and the towns along Route #1 with their VFW halls and Little League fields, shopping strips, warehouses, small factories and crowded residential districts with brick two and three-storey houses, many of them looking east, across the Hudson, over the hump of the Palisades, towards the high-rise towers of Manhattan. These landscapes again are often devoid of humans, except when they serve as scale or visual inflection – appearing in the shadows of a doorway or awning, for example. The one major exception to this is his book Artie Van Blarcum, a collection of photographs of an amateur photographer Tice met in 1960 at various camera club gatherings and competitions. ‘Artie is a 52-year-old bachelor who works in a factory (as did his father and grandfather), in Bloomfield, where fire extinguishers are manufactured. He lives in the same house he grew up in with his brother Billy, their dog Prinz, and cat Red.’ Facing most of the photographs of Artie’s domestic life is a written commentary, supplied by Artie himself. Beside a photograph of Artie and Billy having dinner, is this squib, entitled ‘Snacks’: ‘Billy’s on a diet. He starves himself at suppertime: no grease in his cooking, no bread, no sugar in his tea. But piled up by the side of his bed are big stacks of candy bars. At night he rations out the television snacks. He’ll put out a few chips in a bowl, then put the rest away for the next night.’

The absence of human forms except as props makes Tice resemble Edward Hopper, as he does in a variety of other ways: subject matter, a sense of desolation or loneliness. Tice’s Phone Booth, 3 a.m., Rahway, New Jersey, 1974, with the lit booth placed beside an empty highway, with heavily shadowed trees in the background, could not be any more Hopper-like. I had the same reaction to Tice’s New Jersey landscapes when I first encountered them in the late 1970s through a photographer friend as I had when I first saw Hopper’s paintings at the Whitney Museum, where my father liked to drag me when I was a child: I know this! This is ART? I was mesmerised, thrilled. When my friend first showed me Tice’s White Castle, Route #1, Rahway, New Jersey, 1973, I told her that one day I would have the image on the cover of a book of my poems. It took me thirty years. The affinities between the two artists are evident not only in Tice’s urban landscapes but in any number of his more rural or small-town photographs, such as Porch, Monhegan Island, Maine, 1971 (from Seacoast Maine). These images are not meant as homage. Tice simply arrived at a similar aesthetic and had a fascination with kindred subject matter and forms. They share a realism grounded in silence.

Tice’s photographs can be as pictorial as early Steiglitz – Houseboat, Jersey City, New Jersey, 1979 – or as starkly documentary as Walker Evans: National Barbershop, Bay Circle, Elizabeth, New Jersey, 1990. He is difficult to characterise. There is a formal quality to his work. The photographs are very much composed. There’s almost nothing of the glancing provisionality of the earlier generation of New York photographers, or the street photographers who are his contemporaries. There is a stillness and classical sense of balance to his work that makes it seem to belong, often, to an earlier era.

William Carlos Williams, inevitably, comes up in discussions of Tice, being, in his own work, very much rooted in New Jersey, particularly East Rutherford and Paterson. When Manhattan does make an appearance, the great metropolis is usually viewed across the Hudson River from the Jersey side. The two artists also work the same patch aesthetically. They are both keen on documentary, getting it down, the truth of it, without adornment. Both men are interested in the vernacular, in the larger sense of the term, and in the lives and habitats of working men and women: architecture, speech, subject matter. Some might characterise them as fetishising the ordinary. As someone from that neighbourhood, I’d say that they are after what claims their attention most vividly, what’s in front of them, staring back at them.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.