Maeve Brennan could stop traffic. According to her colleague Roger Angell, she laid waste to a ‘dozen-odd’ writers and artists after the New Yorker hired her as a staff writer in 1949. She makes a cameo as the magazine’s ‘resident Circe’ in a biography of the cartoonist Charles Addams; legend tells that she was Truman Capote’s inspiration for Holly Golightly in Breakfast at Tiffany’s. Was it the clothes? As a fashion editor at Harper’s Bazaar, Brennan wore white gloves to the office, and her vintage wardrobe and showy up-dos must have seemed exotic in the New Yorker’s ascetic halls. She sported a rose in her left lapel, and carried a black and white skunk bag she was ‘inhumanly fond of’. No woman, she said, should wear a bra that cost less than $50 at Saks.

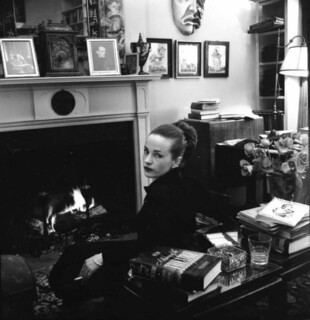

There are plenty of photographs of Brennan, but the one I remember is Karl Bissinger’s from 1948. Her black collar is high, and her eyes look behind him to a corner of the room; she’s not avoiding the camera so much as making herself opaque to it. (‘To turn away,’ one of her characters says, caught gazing at a lover, ‘would be to admit that she had been turned towards him.’) In New Yorker lore, the platitudes used of her – ‘changeling’, ‘fairy princess’ – point to something fugitive, just as the Dublin stories, on which her reputation as a fiction writer depend, have a preternatural ability to seem intimate while keeping the reader at arm’s length. The Bissinger portrait, which appears on the cover of Brennan’s reissued collection The Springs of Affection, reinforces this quality, seeming to echo the ‘lovely’ but ‘unyielding’ sentences that Anne Enright describes in the volume’s introduction. It’s difficult to look at Brennan here and not think of the words she puts in a missionary’s mouth in ‘Stories of Africa’: ‘You could say that an exile was a person who knew of a country that made all other countries seem strange.’

Maeve Brennan was born in Dublin on 6 January 1917. Her parents had both been involved in the Easter Rising. Her mother, Una, was one of the three women who raised the tricolour in Enniscorthy in April 1916, and one of only two women to be admitted to the Irish Republican Brotherhood. After the Rising was suppressed, Robert, her father, narrowly escaped the firing squad, and was in Lewes Prison when Maeve was born. Her childhood was punctuated by raids from ‘unfriendly men dressed in civilian clothes carrying revolvers’; they were looking for her father, who was often on the run. After de Valera came to power in 1932, Robert Brennan became the first Irish emissary to the United States. Maeve was 17 when the family emigrated. In Washington, she took a degree in library science at the Catholic University, and became engaged to the playwright and theatre critic Walter Kerr. He broke her heart. (Years later William Shawn told a colleague that Kerr would never write for the New Yorker ‘because of Maeve’.)

In 1941, Brennan moved to Manhattan and soon found work at Harper’s Bazaar, where she stayed for seven years, rising through the ranks from a copywriter to an editor. Life profiled her in 1945 as a model of modern flânerie, scouring the boutiques of New York for things to include in her columns. Brennan is pictured window-shopping for ceramics on Madison Avenue, and vacillating over a pair of leather sandals (shoes were rationed because of the war); there’s no hint of the crippling anxiety her new status inspired. ‘All my life,’ she told William Maxwell, her closest friend, ‘I was as ashamed of having a little talent as another would be of being born without a nose.’ Good old Catholic guilt. At convent school, the nuns had confiscated her poems and diaries. ‘Don’t go getting any notions,’ Maeve is warned by her little sister in an early autobiographical sketch.

At the New Yorker, with her ‘longshoreman’s mouth’ and ‘tongue that could clip a hedge’, she made her opinions known. Daphne du Maurier was ‘witless’, Jean Stafford her ‘bête noire’. Brennan immediately set her sights on grander things than the fashion notes and short reviews she’d been hired to write. In 1952, her first story appeared; two years later, she had a piece in ‘The Talk of the Town’, the section of the magazine over which Shawn kept the tightest of reins. Brennan’s male colleagues, including Addams, Joseph Mitchell and Brendan Gill (all of them her lovers at one time or another), joked that she had served her apprenticeship in hemlines. But it was the ability to spot the difference between ‘beige’ and ‘bone’ at fifty yards that made her a natural diarist. John Updike said her ‘Talk of the Town’ pieces ‘helped put New York back into the New Yorker’.

Her first column, in January 1954, was about a careless dry cleaner, and began the dispatches from ‘a rather long-winded lady’ whom the New Yorker heard from ‘occasionally’. Introducing 47 of these pieces for a collection published in 1969, Brennan gave a sketch of her alter ego. She ‘thinks the best view of the city is the one you get from the bar that is on top of the Time-Life Building’; she likes taxis and ‘travels in buses and subways only when she is trying to stop smoking’. These columns have the quality of interludes; they’re records of time idly passed between more meaningful events. The long-winded lady skims a beauty magazine over a commuter’s shoulder on the A train; at 5 a.m. she sips a lonely coffee in Bickford’s, and at 3 p.m. she plunges a half-drunk martini out of the sightline of two passing nuns. But it’s all quite gloomy and solitary, as if she’s stuck in an Edward Hopper painting. The effect of reading about the lady is strange; you’re struck by the poignancy of your own mundane rituals, as if, all of a sudden, you were drunk.

Brennan wanted to write ‘as though the camera had never been invented’. She’s a born snoop. Hidden behind a detective novel, she eavesdrops on ‘a socialist who is interested in lust’. She spies on a couple having a row, and wonders how ‘she’ must have felt to see ‘him’ – ‘Animal Lover, Persecutor of Women at six o’clock in the morning’ – bend down to pet a poodle when he’s just jilted her in Washington Square Park. But what worries race through the lady’s head as she loiters off Fifth Avenue, ‘feeding an expensive Plaza Hotel brioche to some pigeons’? The absence of clues to her thought is curious, not least because Brennan had battled to be allowed to write her pieces in the first person.

What I’m looking for, maybe unfairly, is a way of reconciling the Brennan who basked in the ‘lavish solitude’ of ‘small, inexpensive restaurants’ – ‘the home fires of New York City’ – with the Brennan who sparkles in her colleagues’ memoirs. The New Yorker columns bear no trace of the woman who went to a party hosted by E.B. White and silenced the room by yelling: ‘Fuck you, Brendan Gill, you goddamn Roman Catholic!’ In her own telling, or the lady’s, her evenings sound desperately lonely: Billie Holiday on a loop, all that rain, all those cats. It’s difficult to imagine this being the same woman who, working on a corridor nicknamed Sleepy Hollow, pegged the door open, brought in potted plants, and painted her office ceiling Wedgwood blue. Maxwell remembered ‘so much slipping of notes under [Gill’s] door, and hers, and mine, and so many explosions of laughter as a result of our reading them that … Mr Shawn decided it wasn’t good for the office morale’; Brennan was moved to the other side of the building. Her impression of Broadway, a fray of contradictions – ‘so blatant and secret, so empty and alive, so unreal and familiar, so private and noisy’ – reads like a self-diagnosis.

In 1954, aged 37, Brennan married St Clair McKelway, formerly the New Yorker’s managing editor, an ex-pilot and manic depressive who was fond of women and drink. Maxwell wrote that ‘it may not have been the worst of all possible marriages, but it was not something you could be hopeful about.’ To another acquaintance, they were ‘like two children out on a dangerous walk: both so dangerous and so charming’. When they weren’t hiding out in McKelway’s country house upstate, they could be found chain-smoking in Costello’s on 44th Street, downing martini after martini, ‘until in the early morning’ Brennan would ‘punish him by passing out, and her exquisite head would pitch forward upon the bar, as if guillotined’. Attempts to dry out were unsuccessful; Brennan returned from one visit to Ireland to find McKelway waiting for her boat, completely slaughtered. ‘I thought you were on the wagon!’ she wailed. ‘I got up to give my seat to a lady,’ he shot back. In December 1959, the couple agreed to divorce. Brennan never remarried, and she all but abandoned romance. ‘What makes a waif?’ she had asked in her story ‘The Joker’ (1952). ‘When do people get that fatal separate look? Are waifs born? … Sometimes you could actually see people change into waifs, right before your eyes. Girls suddenly became old maids, or at least they developed an incurably single look … It was a shameful thing to be a waif, but it was also mysterious.’ She told Edith Konecky she’d never enjoyed sex, and had it ‘out of pity’ for the men whose company she liked: ‘They wanted it so much, poor things.’

After splitting from McKelway, Brennan moved from hotel to hotel. She was ‘like the Big Blonde in the Dorothy Parker story’, Gardner Botsford wrote: she could ‘transport her entire household, all her possessions, and her cats – in a taxi’. Searching for an area in which to ‘settle down’, she tried Hudson Street, 22nd Street near Ninth Avenue, Sullivan Street, Ninth Street near Fifth Avenue; but nowhere stuck. She had parquet floors installed in an apartment she was renting in Greenwich Village, then left it empty until the lease expired because she preferred living in the Algonquin. What she liked about it – as with the Westbury, Lombardy, Royalton, Iroquois, Prince Edward and all the others – was the idea that she could check out at any time. The appeal of Manhattan, it seems, was its ‘tacky temporary air’. Brennan wrote beautifully of the ‘transience’ of the city’s ‘two horizons’: one architectural (‘impermanent and stony’) and the other natural (‘created when water and sky work together in midair’). Her best columns are records of a city under siege from urban developers; of streets choked with ‘white wrecker’s dust’ clearing the way for ‘noseless architecture’. When Midtown was levelled in 1968, she felt the thrill of a child who sees their dolls’ house opened up: ‘One minute the brownstone is standing, deserted, stripped, and empty, and the next minute … its front is gone and its insides are showing, daylight streaming like cold water over curved staircases and papered walls and small interiors – doors and ceilings and corners that remain secret even with everybody looking at them.’ Her columns are vivid depictions of what Jane Jacobs called ‘the ballet of the city sidewalk’, but they also display a fascination with the forces that were making that life extinct. In ‘The Last Days of New York City’ (1955), she considers the ‘rumour’ that Robert Moses planned to run ‘an underpass through Washington Square’, and imagines her hotel with its roof off: ‘It would make a creditable corpse.’ ‘All my life,’ she wrote, ‘I’ll be scurrying out of buildings just ahead of the wreckers.’

It was Brennan’s gift, and her trouble, that she saw things most clearly when they were half-destroyed. In her non-fiction, the transience of Manhattan is described with an intensity befitting a love affair. Listen to her talking about Sixth Avenue: it ‘possesses a quality that some people acquire, sometimes quite suddenly, which dooms it and them to be loved only at the moment when they are being looked at for the very last time’. This makes it all the more strange that one house stands immovable at the centre of her fiction: 48 Cherryfield Avenue in Ranelagh, Brennan’s childhood home. The Dublin stories that made her name are, almost without exception, set here. Collected posthumously as The Springs of Affection (1997), they appeared in the New Yorker between 1953 and 1973, and consist of early autobiographical sketches and two short-story cycles about unhappy marriages. First, there’s the doomed union of Rose and Hubert Derdon, whose only son, John, has ‘vanished forever into the commonest crevasse in Irish family life – the priesthood’. Later, Brennan wrote about Martin and Delia Bagot, whose daughters are based on Maeve and her younger sister. To read The Springs of Affection is to allow 48 Cherryfield Avenue to become part of your mind: the narrow staircase with its wine-red runner, the panel of brass around the hearth, the long French windows in the front room, the laburnum in the back garden and the tennis club behind that.

Maxwell said that Brennan’s fiction was distinguished by ‘almost clinical descriptions of states of mind’. The emotions in her stories – envy, pettiness, regret – are those that find expression in the footnotes of life. A penny is lost between two floorboards; a couple bicker over the last slice of fruit cake; a dying man reaches for the font of holy water only to find that it’s dry. Brennan had a term for the digs, from name-calling to tantrums and pranks, that people ruined by disappointment use to get their kicks: she called it ‘evil mirth’. In The Visitor, an early novella unpublished in Brennan’s lifetime, Mrs Kilbride threatens suicide if the daughter she calls ‘Other Self’ marries the architect she’s fallen in love with. Hubert Derdon punishes John’s fetish for holy pictures (and Rose’s devotion to their son) by spreading an image of St Sebastian on his bread, as if it were butter, and biting it. In ‘The Rose Garden’, the crippled Mary curses her little girl for siphoning off her husband’s love: ‘I wish to God she’d been born crooked the way I was. There’d have been no pet child then.’

Brennan had the remarkable ability to move from a brutal one-liner to something more expansive and humane, as if she were merely switching camera angles:

When Hubert first saw Rose, he thought how light and definite her walk was, and that her expression was resolute. He never learned that the courage she showed came not from natural hope or from natural confidence or from any ignorant, natural source, but from her determination to avoid touching the two madnesses as they guided her, pressing too close to her and narrowing her path into a very thin line. She always walked in straight lines. She went from where she was to the place where she was going, and then back again to the place where she had been.

The rhythm of the long middle sentence gauges the movement of a body on a tightrope; the commas fall like knives, as one foot is placed in front of the other. Rose’s agility, we’re made to understand, derives not from grace but fear. This is Hubert, remembering her expression at the moment he proposed to her: ‘“It was careless of me to fall into this deep water,” her face seemed to say, “and I am all to blame for not having learned to swim, but even though I was stupid, not learning to swim, and even though the water is deep, I do not want to drown.”’ We never know, maybe couldn’t know, which one controls the other’s future; who’s holding the knife and who’s going under it. There’s such subtlety to Brennan’s writing that one might momentarily forget who’s in command of the narrative; that only Brennan could write Rose out of this situation, or force Hubert to empathise with his wife. No chance. Again and again, we watch her bid farewell to the people she’s made, as they edge towards the unhappy ending she’s prepared for them.

To be around Brennan, Maxwell wrote, ‘was to see style being invented’. But at what cost? In a letter from 1965, she cast the writing process as a precarious endeavour, requiring something like Rose’s spurious agility. There’s a ‘specific difference’, she explained, ‘between those writers who possess the natural confidence that is their birthright, and those fewer writers who are driven by the unnatural courage that comes from no alternative. It is something like this – some walk on a tightrope, and some continue on the tightrope, or continue to walk, even after they find out it is not there.’ The painstaking composition of her Dublin stories – some of which took a decade to finish – was a sort of compulsion. It arose, at least in part, from her desire to transfer ‘the disgusting guilt’ about her family to her ‘poor work’. Angela Bourke’s biography is good on the diffidence of Rose Derdon and Lily Bagot, and its roots in Brennan’s disillusion with her mother, a radical who was ‘reduced to silences and domesticities’ in her middle age. And even those sceptical about conflating a writer’s life and work will find it difficult not to see Bob Brennan as the prototype for the jealous parents who haunt his daughter’s stories. It was on account of his writerly aspirations that Brennan was riven by guilt at her own success. ‘The pain radiated by the Envious One,’ she wrote to Maxwell, ‘is terrible to endure’; a month after her father’s death, she confided to her diary: ‘I see him, bones, white hair, faded eyes, courage, wonder, naked envy, malice, longing, & high dreams, dedication, bewilderment.’ No doubt she connected his ‘frightful’ bitterness to his politics. She herself turned away from her father’s Fenianism, believing it involved ‘licking old wounds instead of getting on with things’; then again, ‘licking old wounds’ would do as a shorthand for most of her stories, and she occasionally proved far from immune to the romance of Irish insurrection. When Maxwell suggested she read the Anglo-Irish Elizabeth Bowen, Brennan took back, without a word, a favourite portrait of Colette that she had hung behind his desk. Later, visiting London, she was ‘outraged’ to find that the only available map of the city was ‘the one with the “Bastion of Liberty” on it’. (‘Blood tells,’ she wrote.)

Did Brennan keep writing about her family because she couldn’t get them off her mind, or was dwelling on her family what enabled her to keep writing? Probably both. More than thirty years after she left home, the ‘disgusting guilt’ still gave her nightmares:

The last week or so, 2 or 3 times, I woke up with the most painful awful feeling of irrevocable separation from something I could put my hand out and touch – I was in New York City & had come from Washington & they were in Washington & the sense of time drawing tight from nowhere to nowhere was, the 2 or 3 times or so, agonising, as though the feeling I woke up with was incurable & would last for every minute as long as I lived. It was as though I could see them & they were wondering about me & didn’t know I was dead. And I didn’t want them to know.

From the mid-1960s onwards, Brennan spent long periods alone in the country, and less and less time at the office. ‘All we have to face in the future is what has happened in the past,’ she complained, as she retreated further into it. She began to dictate her reviews over the phone. The more solitary she became, the more life flowed into her fiction, as if isolation and memory were twin preconditions for its creation. (‘The fewer writers you know the better, and if you’re working on anything, don’t tell them’; ‘You are all your work has. It has nobody else and never had anybody else.’)

She had financial troubles. ‘I feel as Goldsmith must have done,’ she confessed to Maxwell, that ‘grown-ups ought to pay the big ugly bills.’ In January 1964, the credit manager of Saks wrote to the New Yorker making a final request for Brennan’s outstanding balance of $1840.70. Not for the first time, the magazine stepped in. But Milton Greenstein, who took control of its purse strings in 1966, was less tolerant of Brennan’s spending than his predecessor had been. During their marriage, neither McKelway nor Brennan had bothered to file tax returns, and in 1970 the government noticed. Brennan begged for Maxwell’s help – ‘If they come in with a lien all that business of the LETTER will come up again … Milton will die of ulcers’ – and, once more, the New Yorker bailed her out. Brennan continued to live in the country and continued in the red. ‘I can’t even pay the milkman for my cottage cheese and orange yoghurt, and I have to walk 2 miles to make a phone call.’ And then, the kicker: ‘Of course it may be that none of this is really happening and that I have gone stark staring mad.’

What’s disturbing about reading Brennan’s stories alongside her biography is the growing sense that they were destined to converge. Everywhere in the fiction you encounter beggars, waifs, homeless unfortunates. Rose Derdon has a ‘constant stream of poor men and women … coming to her door to ask for food or money’; she hands out heirlooms – her dead mother’s brooch, her son’s baptismal shawl. In an early autobiographical story, Brennan’s mother is harassed by a ninety-year-old man who comes to her house every Thursday selling apples. In ‘The Joker’, Isobel takes a beggar in on Christmas Day, and he punishes her kindness by plunging a cigar into the sauce for the plum pudding. The Visitor ends with Anastasia being refused a home by her spiteful grandmother; when we last see her, she’s walking barefoot in the street and singing, a lost girl ‘full of derision and fright’.

Brennan’s best, most controlled stories were published just as her life was unravelling. ‘The Springs of Affection’, widely acknowledged as her masterpiece, appeared in the New Yorker in 1972, the same year Konecky met her at MacDowell Colony wearing a brown paper bag over her head. It’s spoken in the voice of Min Bagot, a spurned twin who harbours a lifelong grudge against the sister-in-law who dragged her brother Martin ‘all out into the open where blood didn’t count’. This is a story about ‘the gradual destructiveness of love, the erosion of the spirit through need’, as Brennan wrote of Colette’s work; Bourke describes it as a ‘kamikaze flight’ in which Brennan reaches her pinnacle as a fiction writer through a ‘suicidal assault on her own family’. For Min, Brennan borrowed the biographical details of a great-aunt, Nan Brennan, but transformed her into a monster; through the thinnest of veils, she was effectively alleging that she had committed her sister to an asylum not because she was mentally ill – which does appear to have been the case – but because she had given away the German china their mother had treasured. After ‘The Springs of Affection’ appeared in the New Yorker, Nan took a ten-year-old photograph of her niece and scrawled on the back: ‘Maeve: greatly changed for the worse, 1972.’

In the early 1970s, Brennan’s paranoia became full-blown. She began to suffer psychotic episodes, hiding in a colleague’s apartment because ‘they’ were trying to lace her toothpaste with cyanide. She took to sleeping in the cubicle next to the ladies’ room in the New Yorker building, and would cash her paycheque at the Morgan Guaranty Trust so she could hand out cash to passers-by. Greenstein tried to counter this by paying Brennan in instalments; she threatened to sue. (She was fond of Conrad’s claim that ‘a certain degree of self-esteem is necessary even in the mad.’) Her colleagues begged Shawn to intervene, but he would bustle away, repeating only: ‘She’s a beautiful writer.’ The final straw came when Brennan trashed Philip Hamburger’s office, wreaking particular violence on photos of his sons. Not long afterwards, she was persuaded to get psychiatric help.

After she was released from hospital in the summer of 1973, Brennan spent some time in Dublin, but the rain was ‘not the constant rain’ she’d been ‘half hoping for’, and the estate agent couldn’t find a property that pleased her. Returning to the US, she moved into a hotel near the New Yorker, and by 1975 had once again stopped taking her medication. The magazine’s staff were ordered not to let her into the office. Brennan died in a nursing home in Queens in 1993; her last twenty years were troubled and peripatetic, and their particulars are largely lost to us. As early as 1973, she was writing to Maxwell from Dublin with a sense that her life was winding down:

If you think, sadly perhaps, that I have regrets, you are wrong. I have no regrets at all … It is nice to be able to say that I spent my years. I would hate to have to say that I misspent them. If I should be hit by a car, please comfort yourself with the knowledge that I died happy, although, dear me, outside the church. THE church.

Much is made of Brennan’s darkness, but even in those bleakest of days she could sound a terrific comic note.

In ‘The Lie’, Maeve throws her sister’s sewing machine out of the window, and then confesses to the priest. Does it take being dragged up in the faith to understand the twisted logic that makes her mother angrier about the telling than about the throwing? And would those who were never herded into the choir of an Irish convent know that Brennan isn’t overstating the case when, in ‘The Devil in Us’, a poor singing voice is taken as an indication of resident evil? ‘If God had been on our side,’ one of the tone-deaf girls thinks, ‘surely He would have given us the voice to sing His praises.’

The Rose Garden, which contains some of her funniest stories, was the only collection of Brennan’s work not reissued for her centenary last year. Its stories are set in ‘Herbert’s Retreat’, ‘an exclusive community of about forty houses on the east bank of the Hudson, thirty miles above New York City’. (Its real-world counterpart, Snedens Landing, was the location of McKelway’s country house.) These are Upstairs, Downstairs comedies in which Irish servants wreak gossipy havoc on their American bosses. Maxwell never liked them as much as the Dublin stories, feeling they ‘lacked the breath of life’; nothing is further from the truth. Of a gold-digger: ‘That rip hasn’t got a nerve in her body.’ Of the gold-digger’s first husband: ‘He was dead drunk and ran himself into a young tree. Destroyed the tree and killed himself. She had to get a new car.’ Of the gold-digger’s pursuit of a river view: ‘Cut the hedge. God almighty, she couldn’t get it down soon enough. I thought she was going to go after it with her nail scissors.’ These stories cackle with ‘evil mirth’. When one New Yorker reader wrote to the magazine in 1959, asking for more of the Irish hired-helps, it was Brennan, in the spirit of those stories, who drafted a reply:

I am terribly sorry to have to be the first to tell you that our poor Miss Brennan died. We have her head here in the office, at the top of the stairs, where she was always to be found, smiling right and left and drinking water out of her own little paper cup. She shot herself in the back with the aid of a small handmirror at the foot of the main altar in St Patrick’s Cathedral one Shrove Tuesday. Frank O’Connor was where he usually is in the afternoons, sitting in a confession box pretending to be a priest and giving penance to some poor old woman and he heard the shot and he ran out and saw our poor late author stretched out flat and he picked her up and fearing a scandal ran up to the front of the church and slipped her in the poor box. She was very small. He said she went in easy … We will never know why she did what she did (shooting herself) but we think it was because she was drunk and heartsick. She was a very fine person, a very real person, two feet, hands, everything. But it’s too late to do much about that now.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.