A half-painted wall, a bowl with a wobbly lip, the cracked shell of a crab, hair that hasn’t been brushed yet that morning: there is a certain beauty in unfinished things. It is a sort of beauty that is uncalled-for, unearned even, and so it is annoying too: the crosshatched brushstrokes of white emulsion are accidental; the crab’s golden-orange back is just on its way to ruin; the expensive haircut looks its best after eight hours of your lying on it. The beauty doesn’t last – it isn’t meant to. It is something that happens along the way, that surges up out of almost nowhere. Sometimes it is the only sort available, and to believe in it may be the only way of getting things done.

The existence of Crudo, the first novel by Olivia Laing, who has written three books of non-fiction, was first announced on Twitter on 1 August 2017:

Tipsy over dinner, I have come up with a quartet of novels which I am going to write in the first year of the next four decades.

Or forget entirely by breakfast.

argh the titles are so good!!!!!!

Then a day later: ‘Update: I’ve written the first paragraph of the first volume on a sun lounger and it is very amusing.’ And then later that day: ‘Aperitivo, I wrote 2000 words !!!’ with a photograph of the writer in sunglasses, Campari in hand, against an Italianate blue sky. Laing had been reviewing Chris Kraus’s biography of Kathy Acker for the Guardian; she had been holidaying in Val d’Orcia with her newish husband, Ian Patterson, the Cambridge academic and poet who was Jenny Diski’s husband until her death in April 2016; she was tweeting about Sam Shepard and Brexit and the Booker shortlist and a new Laure Prouvost show and Charlie Gard and Call Me by Your Name and cab drivers in Rome and John McCain’s part in the GOP vote to roll back Obamacare. And a year later, almost to the day, here is Crudo – born of accident, on holiday, like a dare – and it is already on the Sunday Times bestseller list.

‘Kathy, by which I mean I,’ it begins, ‘was getting married. Kathy, by which I mean I, had just got off a plane from New York.’ The narrator – who has written Kathy Acker’s Great Expectations and Blood and Guts in High School and is called Kathy but is still alive after Acker’s death from breast cancer in 1997 – has bought two bottles of duty-free champagne in orange boxes: ‘that was the kind of person she was going to be from now on.’ She is being met by her future husband at the airport. Kathy will soon be broken up with by the man ‘with whom she was sleeping’ by a letter ‘on headed writing paper. He didn’t think two writers should be together … The man with whom she was sleeping had not written any books. Kathy was angry. I mean I. I was angry. And then I got married.’

The prose is instantly confessional, with a directness that most reminds me of emails I’ve received rather than books I’ve read. But in emails you talk of yourself in the first person without trouble or hesitation, and this narrator can’t quite settle on herself. Going back and forth between ‘she’ and ‘I’, as if a non-fiction writer were reminding herself to inhabit a character from the inside, the prose is an engine not quite yet warmed to a purr. Or is it deliberately not purring: is it stuttering instead, punk-like in its refusal to keep to the rules of the novel, like the work of Kathy Acker? And more than that, what if it’s the stuttering that makes the writing possible? Acker’s legacy is generous: it gives permission to steal from the top of the canon to its dregs, to talk of fucking and break-ups and incest, and not to be very neat about point of view while doing it. Stealing from Kathy herself provides the cover needed for a novel to be new when its first line announces that it occupies the most ancient novelistic territory of all. (Or, as Kathy puts it halfway through Crudo: ‘What’s the novel about if not getting fucked?’)

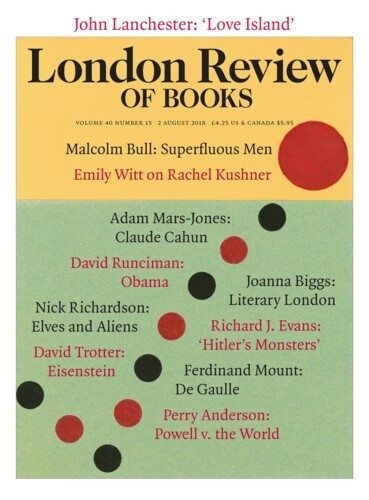

And Crudo does announce itself on its cover as a novel, even though what it requires of the reader isn’t what novels ordinarily require. Before publication, Laing wrote an article for the Sunday Times about the biographical circumstances that brought about the book, fleshing out the detail from her Tweets: yes, she wore Isabel Marant to get married as Kathy does in the novel; yes, her husband is called Ian as Kathy’s is in the novel; yes, she took him to the River Café for his birthday as Kathy does in the novel. We knew all this and more to be true, literally true, when we opened it. It isn’t that the sentences are difficult in Crudo, or the subject matter alien: it is rather that Crudo sits somewhere between a roman à clef and autofiction, the hip blend of fiction and memoir associated with writers like Knausgaard, Ben Lerner or Sheila Heti. If most of Crudo is true, then what does the novel gain by being a novel at all? At the back of the book, all the quotations are identified, providing a key of sorts. But Laing’s own Twitter feed is another key to the novel, as is the sort of knowledge of literary London that means you might know what the poetry prize being referred to is, or who Mitzi, Mary-Kay, Andy and the first owner of a plate that used to belong to Doris Lessing are. The novel doesn’t have one key, but several keys, with the last probably belonging to Laing herself. It’s like the hyperreal Wolfgang Tillmans photo on the cover of a fly landed on a crabshell that has been broken open: the detail is of such a lurid resolution you think it false, only to find out that it’s true. The confusion may be part of the appeal.

Kathy is on her sunlounger ‘under a hornets’ nest in the Val d’Orcia’. She is two weeks away from being married: they have been to the register office for their interview and have chosen their music (‘she’d insisted on Maria Callas because she didn’t operate via understatement’) and she is surveying the diamond on her hand:

Last night, before going out, she’d had a serious conversation with her husband about marriage. I don’t like proximity, she told him. But why he kept saying. What’s the source of that feeling. It wasn’t a feeling that had a source, except in the way the source of hayfever is flowers. It was just she kept sneezing, it was just that she needed seven hours weeks months years a day totally alone, trawling the bottom of the ocean, it’s why she spent so much time on the internet. So you like talking but you don’t like it when people talk back her husband said rudely, but that wasn’t quite it. She just didn’t know how to deal with someone else being there, especially asleep. She was right on the edge of the bed, she was doing her best. In two weeks she’d make official promises, in language as embarrassingly hewn and potentially hubristic as the Labour manifesto Ed Miliband had had carved into stone. Where was that stone, she wondered. Had it too been turned into tarmac? Were all the roads in England composed of memorials that had become publicly toxic? She looked on the internet. The EdStone was in the garden of the Ivy.

The hallmark of Kathy’s thought is a sort of zig-zagging anxiety. Elsewhere in the novel she describes herself as ‘not unevasive’ and talks of hearing voices that speak to her in ‘a sort of impassioned mumble, a communicative withholding tone’. Here she starts by outlining the most persistent worry in the book: that she is not cut out for marriage. But even as her husband (she gives him that title before they are married) presses her gently and then more insistently as to why that might be, she moves away into a metaphor about hayfever and then into the grand internet defence: that she needs several hours a day online. She approaches the subject by thinking about the promises she’ll make on her wedding day, but the internet is there again when she compares those vows to the EdStone of the 2015 general election, and googles what happened to it instead of thinking about what she wants to happen to her. It’s a sympathetic sort of evasiveness – stories of unconventional women on the verge of conventionality tend to be – but psychologically it is unsatisfying. The pinball rhythm of the prose creates the sort of movement that doesn’t seem to take you anywhere.

And when Kathy looks to the world – or more accurately, the world of the internet – it is no less anxious. When the wedding day finally comes, she puts on sunglasses and an orange coat over her Isabel Marant dress (see both in the author photo on the back flap), ten sweetheart roses ‘creamy pink, tied with straw’ are conjured into a makeshift bouquet in ten minutes, ‘then they were off, marching to Maria Callas, I do and hereby and turn and face forsaking all others till death. It was actually an openish marriage but yes she meant it.’ Her husband dances out the door and then they drink Le Mesnil and eat husband-made cake and the doorbell keeps ringing ‘when someone shouted Steve Bannon’s resigned. They all checked their phones. Bruce Forsyth had also died, he was older than Anne Frank, but the main news was Bannon. It had literally just happened, no one quite knew why, great wedding present she muttered to no one in particular. Confederate statues were being pulled down all over America, often in the night, mayors were just sending out orders and ripping them down.’ The speed of the wedding day and the speed of the newsday are in sync: momentous shifts are happening and no one knows why or can quite keep up with them. It is all unfinished and happening now. Nothing holds the attention for very long: ‘Everything was hotting up, going faster and faster.’

This is the mode of the novel, alternating between anxiety about becoming a wife to anxiety about the state of the world and back again. Laing wrote in the Sunday Times that she thought of the novel as a ‘cast’ taken of the first weeks of her marriage (which she adds is ‘calmer now, a little more regularised, a little more steady’) but there is something empty to the anxiety: after all, the Trump administration didn’t fall when Bannon did; Laing did get married and is still married. Experiencing the relentless now of last summer from the relentless now of this World-Cup-Love-Island-flossing-craze summer is strange: when it doesn’t seem futile that we worried about Bannon and North Korea and Bruce Forsyth, it seems desperate that we’ve already forgotten about the floods in Houston and the iceberg that broke away from the Larsen C iceshelf. Kathy is the right person to channel this anxiety – she almost plays it – but she is too in the moment to make much sense of it. When there’s nothing other than unfinishedness, why not get into it? Why not try and see the beauty in it?

Almost despite herself, that is what Kathy does. Most often she sees it in the natural world: that New York spring was the most beautiful she’d ever seen, ‘so green and excessive, so floral and bosomy and bedecked’; she wakes up two-days-married at ‘dawn, the greyish wheat was gone and the stubble was gold, the straw organised in shining lines’. Her anxiety begins to abate; the speed and the numbness it brings on in her can be fought by this sort of noticing, the sort that can be turned into art. (Kathy describes her husband’s poetry as like ‘someone wiggling a key in the lock of language, it’s jammed, it’s jammed, and then abruptly stepping through’.) She eats a crab with her husband that doesn’t yield its meat on the first hammer crack and realises ‘she wanted to be cracked open, that was the thing, only on her own terms and within preordained limits.’ Don’t we all? And isn’t that one of the hardest things to do?

In the middle of her life’s journey, Kathy has found herself under a hornets’ nest in Val d’Orcia rather than in a dark wood. And so perhaps we can forgive the sentimental ending, as she is boarding a plane for New York again, leaving a husband she will soon return to, now she has learned that ‘she’d never loved anyone before, not really. She’d never known how to do it, how to unfold herself, how to put herself on one side, how to give.’ It could be the novel that has literary London in a tizz this summer isn’t for literary London at all, but written to explain something to one person only.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.