The history of domestic life is not a new subject. Like so much else, it was pioneered in the Victorian age, when the cult of domesticity reached its peak. In 1852 the composer Henry Bishop relaunched ‘Home, Sweet Home’, the parlour ballad which the opera singer Jenny Lind made wildly popular. Ten years later the great antiquary Thomas Wright published his History of Domestic Manners and Sentiments in England during the Middle Ages. Reissued in 1871 as The Homes of Other Days, it contained more than three hundred illustrations drawn from medieval manuscripts by the brilliant engraver F.W. Fairholt. Wright was highly informative on domestic lighting, heating, meals, clothes, furniture and recreations, though not as strong on the building and layout of the houses in which people lived. This gap was filled by Thomas Hudson Turner, who worked on household accounts and planned a three-volume work on medieval domestic architecture. It was completed after his death (in 1852) by another architectural historian, John Henry Parker, who also drew on it for Our English Home: Its Early History and Progress (1860).

Despite this encouraging start, the emergence in the later 19th and early 20th centuries of modern history as a university subject did nothing to advance the study of domesticity. The topic was not thought worthy of attention by the academic historians of the day, who saw their subject matter as public affairs, not private life. It was left to a couple involved in the Arts and Crafts movement, the architect Charles Henry Bourne Quennell and his wife, Marjorie, a painter, to produce four volumes of an immensely successful History of Everyday Things in England, published between 1918 and 1934. Addressed to teenage readers, and wonderfully illustrated by the Quennells themselves, the work was intended to bring them closer to the people of the past by ‘understanding something of the houses they built, the rooms they lived in, the games of their children and the everyday household things they used’. By the 1960s it had sold more than a million copies.

Only in the aftermath of the Second World War did academic historians begin to share the Quennells’ preoccupation with ‘everyday things’. The change owed something to postwar consumerism, which generated an interest among economic historians in the history of goods and their consumption. The study of objects also drew strength from the boom in archaeological excavation which accompanied the rebuilding of British cities. The publications of the Societies for Medieval and Post-Medieval Archaeology demonstrated that the unearthed ceramics, glassware, jewellery, pins, needles, gloves, shoes, buckles, clasps, kitchen equipment, ornaments, tools and weapons together revealed dimensions of the past impossible to glean from documentary sources alone. The collections in the Museum of London show just how varied and instructive these finds, from chamber pots to children’s rattles, have been.

The Society for the Protection of Ancient Buildings (SPAB), founded in 1877 by William Morris and others, had long opposed proposals to alter or destroy remnants of the past. The listing of historical buildings began in 1882, but intensified after 1945 and was greatly extended in the 1980s. The Vernacular Architecture Group, formed in 1952, did much to encourage the study of traditional dwellings and the uses to which they had been put. In its last decades, before it was absorbed by English Heritage in 1999, the Royal Commission on Historical Monuments (England) published Eric Mercer’s excellent survey of English Vernacular Houses (1975) and followed it with thematic volumes on cottages and farmhouses.

The micro-historical study of everyday life also derived inspiration from the late Victorian and Edwardian social surveys made by Charles Booth, Seebohm Rowntree and Beatrice Webb. It was buttressed by the traditions of anthropological fieldwork – most notably the Mass Observation project, founded by Tom Harrisson and others in 1937 – and furthered by the History Workshop movement launched in 1966 by Raphael Samuel. The modest social origins and leftish sympathies of many academic historians had generated a concern with the lives of ‘ordinary’ people rather than those of the political, social and intellectual elites. In subsequent decades, feminist historians drew attention to the unsung millions of women whose lives had been bounded by the domestic sphere.

These preoccupations were further encouraged by powerful influences from the Continent. In his study of the Kabyle of North Africa, Pierre Bourdieu showed how their values were shaped by daily interaction with the objects in their homes. His concept of habitus was founded on the belief that ways of thinking and behaving were closely related to domestic environments. In Germany advocates of Alltagsgeschichte (the history of everyday life) urged the study of the daily experience and subjective feelings of ordinary citizens. Another formidable source of inspiration was the three-volume Critique de la vie quotidienne (1947-81) by the Marxist philosopher Henri Lefebvre. Along with Fernand Braudel’s Les Structures du quotidien (1979) and the Jesuit Michel de Certeau’s influential L’Invention du quotidien (1980), it encouraged the more portentous British historians to discard the words ‘daily’ and ‘everyday’, and refer instead to ‘the quotidian’.

The result of all this is that the historical study of physical objects, once the preserve of museum curators, has become a widespread preoccupation of historians, dignified as the study of material culture. As the analysis of probate inventories has revealed, the early modern period was notable for a huge expansion in the number and variety of objects to be found in ordinary households, as well as in the luxury goods of the well-to-do. Clothes, furniture, ceramics, food, embroidery, wall paintings, plasterwork, glassware, textiles, books, jewels: all have been the subject of intensive research and most of them now have their own specialist journals. The belief that material objects can provide direct entry to the past is reflected in the titles of many well-known history books: Consumption and the World of Goods; The Social Life of Things; The Empire of Things; Superfluous Things; and, echoing the Quennells, A History of Everyday Things. Neil MacGregor’s A History of the World in 100 Objects has spawned numerous imitations, from the Smithsonian’s History of America in 101 Objects to A History of Religion in 5½ Objects.

Similar energy has been devoted by local historians to the study of evolving house-types. W.G. Hoskins’s celebrated essay of 1953 on the ‘The Rebuilding of Rural England, 1570-1640’ didn’t allow for regional differences and his timescale was too limited, but his essential argument still stands. The early modern period saw the remodelling of many rural houses. The high central hall, with an open hearth and a hole in the roof, was modified by the introduction of a side fireplace with a chimney and a ceiling which created a new room or rooms above, reached by an internal staircase. Thatched roofs were replaced by tiles. Windows were glazed. The use of rooms became more specialised; and there was greater physical separation between masters and servants, parents and children.

This work on housing and household goods inevitably revived the study of domestic life. Sara Pennell’s The Birth of the English Kitchen, 1600-1850 (2016) is a fine example of the genre. Today there is a Centre for Studies of Home, based at Queen Mary in partnership with the Geffrye Museum of the Home in Shoreditch. The Geffrye was founded by the London County Council as long ago as 1914. Its original concern was with the history of furniture and its first curator none other than Marjorie Quennell.

This is the intellectual background to Tara Hamling and Catherine Richardson’s ambitious A Day at Home in Early Modern England. Although they are firmly empirical in their approach and never cite Bourdieu or Lefebvre, they are strongly committed to the study of what they call ‘materiality’: Hamling is an authority on the decoration of early modern houses with religious texts and imagery, while Richardson has written extensively on the domestic life of the time. In their book they take what is now a vast body of research on early modern houses and their contents one stage further by investigating the ways in which these domestic spaces were used by those who lived in them. In particular, they seek to recover the texture of the domestic life lived by ‘the middling sort’, by which they mean those immediately below the gentry: professionals, merchants and yeomen. They are concerned with ‘the social significance of the household as a site for constructing and shaping early modern experience’ and the role played by ‘non-elite material culture’ in ‘the construction of status and identity’. Their language is different, and so is their subject matter, but their approach resembles that of Mark Girouard thirty years ago in Life in the English Country House.

The book’s splendid illustrations make it a pleasure to turn the pages, but the text itself is uningratiatingly printed in smallish type, with two columns on each page. Moreover, Hamling and Richardson engage in a good deal of methodological throat-clearing. For them, the early modern house is a ‘heuristic subject’ and shopping ‘an inherently identity-forming activity’. Nevertheless, their book is genuinely learned, abounding in rich detail and acute insights. They begin by emphasising the crucial importance of the early modern middle-class household: the smallest unit of government and a model of patriarchal power. It was of fundamental economic importance as a place of production, retailing and consumption; and it was, at least in theory, a lively centre of religious devotion. Domestic life was not something separate from the world of politics, economics and religion. It was in the household that these large impersonal forces were intimately experienced by most of the population; and it is there that we should look to find what patriarchy, gender and social differences meant in practice.

To convey the rhythms of daily existence, Hamling and Richardson structure their book around the events of a typical day in a household, from waking in the early morning to falling asleep at night. The successive stages of a hasty breakfast, a ritualised dinner at midday, and relaxation in the evening allow for the discussion, at appropriate points, of kitchens, food preparation, recipes, table manners, games, embroidery, beds, and attitudes (often fearful) to the night. But larger topics such as house design, room use, interior decoration, work, shopping and the meaning of possessions do not relate to one time of day rather than another and cannot fit convincingly into this scheme. Instead they are arbitrarily assigned to one single point in the day, like shopping, which, most commonly, it’s claimed, took place in the afternoon, or, like work, they have to be discussed more than once.

In their account of change in domestic housing, the authors supplement the work of their many predecessors with a focus on old houses in the West Country, Kent and the Midlands. They are particularly interesting on town houses, which did not usually follow the rural pattern of a single-storey, tripartite structure, with the hall in the middle, buttery and kitchen on one side and a parlour on the other. Instead, they tended to have a narrow frontage, three or more storeys high and two rooms deep, with the finest room on the first floor and the bottom room on the street frontage often serving as a shop, sometimes with the wife sitting there to entice customers.

Hamling and Richardson have much to say about the multiplication of rooms and their increasingly specialised use. They pay careful attention to the location of different household activities, from drying the washing to preparing the meals. They examine the slow decline of the hall as the place for cooking and eating and the emergence of the parlour as a place for reading, music, relaxation and the reception of visitors. But most rooms seem to have remained obstinately multifunctional. The home was the craftsman’s workshop, the shopkeeper’s counter and the administrator’s office. For women it was a place of continuous labour: washing, cooking, cleaning, childcare and, in the countryside, dairying and butchery. Cooking, in particular, appears to have become an increasingly demanding activity, with the growing use of coal, the publication of recipe books, the import of new groceries and the multiplication of utensils. As a contemporary remarked, ‘they are not looked upon to be of any great worth in personals, that have not many dishes and much pewter, brass, copper and tinware, set round about a hall, parlour and kitchen.’ The discussion of kitchen equipment introduces us to a Beatrix Potter world of porringers and pitkins, trivets and skillets, breaders, basters and pottle jugs.

The authors see the early modern period as one of ‘intense change in the form and meaning of household objects’ and of what they rather unhappily call an ‘explosion of possessions’. The grandest piece of furniture was almost invariably the great curtained bed belonging to the master and mistress of the house, the place for intimate night time conversations and, of course, for ‘curtain lectures’, in which wives reproved their husbands. (The rest of the household slept all over the house.) The most common items were chests for storing valuables, tablecloths and other textiles. During the period, the number of chairs and tables possessed by a household multiplied; cushions, carpets, clocks and looking-glasses were introduced; and, eventually, upholstered furniture arrived and, with it, new notions of comfort. Wooden trenchers were replaced by pewter dishes. The coarse pottery of the 15th century gave way to stoneware, slipware, tin-glazed earthenware, glass and eventually porcelain. The authors have much to say about how and where householders managed to buy all these goods. Many furnished their houses by dealing direct with local craftsmen and met their daily needs with visits to the local market town, where grocers and mercers stocked an increasingly wide range of commodities. The socially more ambitious went one stage further by commissioning third parties to do their shopping in London.

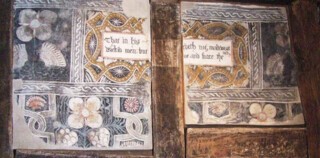

Crucial for the household’s social status was the decoration of the more important rooms with plasterwork, tiles in the hearth, wall paintings, stained wall-hangings, the royal arms, and, very often, religious texts, not all of them cheerful. ‘Make not thy boost of to morowe,’ one ran, ‘for ye knowest not what maye happe todaye.’ Others were the 17th-century equivalents of ‘Take back control’ or ‘Keep calm and carry on.’ The authors recognise that these devout inscriptions are not infallible evidence of the occupants’ piety, though they like to think of their subjects’ days as punctuated by collective prayer in the way recommended by godly handbooks and are perhaps unduly inclined to regard the pious preambles to early modern wills as expressing the real sentiments of the testators.

Privacy does not seem to have been a great consideration. On the contrary, some of the best plasterwork was often reserved for the fore-parlour on the ground floor, so that it could be admired from the street, rather like modern suburban Dutch houses, with their large picture windows, designed to display a meticulously arranged interior for the admiration of passers-by. What the upper middling sort wanted was visibility and recognition in the community. Unlike the gentry, they chose to live in the main streets of towns, and their houses were intended to be conspicuous evidence of their superior status.

Neither does there seem to have been much concern about noise. When the puritan Nehemiah Wallington was disturbed between 3 a.m. and 4 a.m. by someone crying ‘Mackerel!’ in the street, his anger was not occasioned by the disturbance so much as by the fact that it was happening on the Lord’s day. Hamling and Richardson intersperse their account with similar vignettes of daily life, like that of the Worcestershire villager ‘walking somewhere late in the night’ who spotted candlelight in a smith’s shop. Drawing near, he ‘heard a great bustlinge and puffinge and blowinge’ of a couple who were ‘naught together in the sayd shop’ and when the man ‘had donne what he could, he asked her how shee liked it and [she] answered “well eynoughe”’.

Although they would never have included such an anecdote, the Quennells would have applauded this highly informative book. Not that it covers everything. There is very little on clothes, those great signifiers of social difference, presumably because they do not regularly appear in the probate inventories on which much of the research is based. Nor, despite the ubiquity of clay pipes, is there any mention of smoking, even though many 17th-century houses must have stunk of tobacco. Most important of all, although Hamling and Richardson say something about the sentimental attachment to objects, especially those inherited from ancestors, they are silent on the emotional meaning of the idea of ‘home’. The distinctly formal and disciplined regime they describe seems unlikely to have generated much affection. It is often said that men’s work had to move out of the house before the home could be seen as a refuge from the stresses of daily life. Yet it was an Elizabethan proverb that ‘home is home, be it never so homely.’

Buildings and household objects are made by human beings. They in turn help to shape human values and behaviour. Hamling and Richardson claim to have revealed ‘the multiple ways in which the house produced middling identity’. In modern jargon, this is to claim ‘agency’ for an inanimate material object. There is nothing very paradoxical about that, since historians, like architects, have always recognised that human beings are shaped by their physical environment. If climate and terrain can influence people’s habits and values, then why should the buildings in which they live and the furniture with which they surround themselves not have a similar potency? Some would retort that house design is the result of changing social relationships, not the cause. The merging of the dining room with the kitchen in many modern middle-class houses, for example, did not result in the decline of domestic service; it was a response to it. But just as most of us feel obliged to mow the lawn created by the previous owners, so those who find themselves in a house with a formal dining room and drawing room may well feel some pressure to use them in the way their architect intended. One of the many merits of Hamling and Richardson’s book is that it makes its readers wonder whether they are in control of their own domestic environment or prisoners of it.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.