On 17 September 1862, Count Lev Nikolayevich Tolstoy, aged 34, gave his diaries of the last 15 years to Sophia Andreevna Behrs, who had just turned 18. She was the second of three daughters and her mother had been Lev’s childhood friend. Three days earlier, on 14 September, Lev had proposed to Sonya by hand-delivered letter, when her parents had been expecting him to propose to their eldest, Liza, who was twenty. Lev and Sonya had met only at family gatherings and had never been alone together for more than a few moments. On 16 September, Sonya accepted and Lev persuaded her parents to arrange the wedding as soon as possible, on the 23rd. This was extraordinary haste, as if the groom were afraid he might change his mind. Certainly, the gift of the diaries looked like an invitation to Sonya to change hers. The bride-to-be read the notebooks at once, and discovered that Lev had actually been more attracted to her younger sister, Tanya; that he had described her as ‘plain and vulgar’ but erotically exciting; that reflecting on a possible marriage with Liza he had written, ‘My God! How beautifully unhappy she would be if she were my wife.’

It was only the beginning. The reasons a future wife would become unhappy were all too clear. Lev was profligate. He had had endless women of every social extraction. He had caught gonorrhoea from a prostitute. The death of his mother before he was two and his father at eight had meant a troubled childhood, shuffled back and forth together with his three older brothers and one younger sister between quite different households – a religious aunt in the country and a worldly aunt in town. He had failed to finish his degree in law. He had dropped out of a career in the military. He gambled heavily and as a result had lost a great deal of property. His new novel, The Cossacks, had been sold in a hurry to cover his gambling debts.

The consequences of his religious background were hardly less disturbing. Lev was disgusted with himself every time he had sex. All too easily he transferred his self-loathing to the object of his lust. Women were filthy. Yearning for purity, he whored compulsively. He tried to be good, helping the peasants on his country estate, even running a school for them, but in no time at all he would be chasing women again. Even now there was a peasant woman expecting his child. A married woman. Only a few days earlier he had paused in his courting of Sonya to enjoy a country girl called Sasha.

It was a huge amount of information for an inexperienced young woman to absorb in a very short time with a crucial deadline pending. ‘I don’t think,’ Sonya wrote years later, ‘I ever recovered from the shock of reading the diaries … I can still remember … the horror of that first appalling experience of male depravity.’ But she was hooked. Hadn’t she herself, when the family visited Lev, written a short story ‘Natasha’, about a girl who meets an ugly older man, moody and inconsistent in every way, with whom nevertheless she becomes infatuated? She had given that story to Lev, who recognised himself in it. Perceptive and intelligent, Sonya perhaps understood that the proposal of marriage to a well-to-do virgin who was the daughter of old friends represented a desperate attempt to resolve profound inner conflicts. She had read his novels: Childhood, Boyhood, Youth, Family Happiness. By reading his diaries, she would have been able to see that the alter egos he presented in them were idealised, the kind of man he wanted to be rather than the kind he was. Now he meant to use marriage to become that idealised figure. She had been chosen to offer him absolution. It was frightening and hugely exciting.

When the day came, Sonya waited at the altar in the Church of the Nativity of Our Lady, close by her home for an hour before Tolstoy appeared. He had realised at the last moment that he had no shirt for the ceremony. Immediately afterwards, they set off for Yasnaya Polyana, his country estate, 120 miles south of Moscow; and a house with no company, no carpets, no comforts. Nine months later Sonya would give birth to the first of 13 children. While pregnant this teenage wife would make a fair copy from the messy manuscript of a quite wonderful new novel her husband was writing. Apparently marriage had worked. Lev was settling down. Over the next 16 extraordinary years he would publish War and Peace and Anna Karenina.

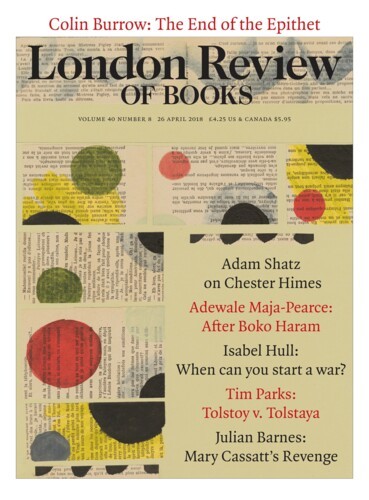

Tolstoy and Tolstaya: A Portrait of a Life in Letters offers 239 of more than 1500 letters the couple wrote to each other in the decades ahead, as Tolstoy became a celebrated author and Sonya his respected wife. It’s a weighty, fluently translated book of 400 large-format pages, a solemn product of serious scholarship, announcing itself, a little self-righteously, as an important tool for future Tolstoy studies. We are alerted to a forthcoming four-volume Russian edition of the full correspondence (to be placed alongside the many volumes of diaries, both his and hers), plus a further English volume offering a critical study of all Tolstoy’s correspondents’ personal and professional relationships. This is an industry. Given how immediately and unreservedly Tolstoy’s character declares itself, even in just a few letters, how evidently and entirely his depressions and enthusiasms overlap with the characters and dramas of the novels, one might wonder at the need for so much more. Especially since Tolstoy’s thinking always tends towards life and action. If he learns Greek and Hebrew and studies the Bible, it is in order quickly to rewrite the holy book as it should have been written and change the world. His sense of urgency is unrelenting. ‘What is to be done?’ is the question asked again and again in the letters, about the family farm, the peasants, the children’s education or toothache, about famine, politics, military service, Russia, the tsar, about a broken wrist, haemorrhoids, stomach pains, a house purchase, a train journey, about censorship, about mankind, about God. Despite Tolstoy’s attraction to monasticism, and occasional pilgrimages to Optina Pustyn, the monastery Dostoevsky made famous in The Brothers Karamazov, he had no idea at all how to let things be.

The early letters overflow with declarations of love and mutual esteem. Sonya begs Lev to hurry back from a hunting trip, or a visit to family or friends. She expresses her admiration for the parts of his novels she is transcribing (while mosquitoes bite and babies whine), laments how dependent she is on him, worries over the children’s illnesses – fever, diarrhoea, whooping cough – describes sleepless nights, disorientation and even terror when he is away: ‘When you’re around I feel like a queen, without you I’m superfluous.’ There are lists of household chores she has done; inspections of the farm stock; money she has spent, lent and borrowed; dealings with decorators, tradesmen, peasants, village elders, English nannies, visitors, relatives and so on. She wishes she could achieve her ‘ideal of the perfect housewife’. As yet there is no criticism, but the reader can feel the pressure building: she is an excellent, affectionate, industrious helpmate. Why is he away so much when he could perfectly well work at home?

In return Lev praises her capacities, speaks of his need to be alone to think, is grateful for her comments on his novel (he feels so insecure as a writer), advises her to keep busy so that his absence will weigh less heavily, says how eager he is for her news, regrets that his love for the children, particularly the boys, ‘is not very strong’. Most of all, though, he talks about himself. First, his health: the broken shoulderblade that keeps him for months in Moscow; the coughs and stomach pains that have him making long trips to Samara on the Volga 700 miles to the east, to cure himself with an exclusive diet of kumys, a mare’s milk yoghurt. We hear of his depressions, which invariably take the form of a loss of purposefulness, a fear that the work he’s involved in – writing Anna Karenina, for example – is meaningless, and prompt an anxious search for some more immediately useful task, such as scything grass, cutting wood and making shoes (all activities that go into Anna Karenina and make the writing of it more reassuringly meaningful). His current ideas and plans are always to the fore (‘I want to write you about what really interests you – about my inner mental state’) and always have to do with how to live and live intensely, but without being contaminated by life. If marriage had conferred a certain stability, it was evident the old conflict was still there. Sonya takes note and never fails to inquire after his mood.

Both correspondents construe their letter writing as a duty. They complain if a day goes by without a letter arriving. They apologise if for some reason they haven’t written. They launch into long explanations of the logistical difficulties of delivery. Soon it is evident that just as Tolstoy’s novels offer him the opportunity to construct an idealised self, a Levin who is so much purer than Lev, so the letters build an ideal marriage. When Sonya begins to sound frantic and critical, Lev suggests that ‘you’re not quite feeling yourself.’ When she is transcribing the novels, participating in his projection of a positive alter ego, she feels safe and happy as though ‘a close friend were sitting with me’; the novel is ‘our “shrine”’. In 1867, five years into the marriage, he observes, ‘I always love you all the more when I’m away from you.’ Soon after she remarks that the two of them are closer in their correspondence than when together. ‘Never,’ he writes in 1883, from a safe distance, ‘have my thoughts about you been so good and absolutely pure as now.’ ‘When you are living together with the family,’ Sonya writes two years later, ‘you are more distant than when we are not together.’

All this is ominous, yet nothing prepares one for the shock of finding, on turning to the chronology tucked away at the back of the book, Tolstoy’s diary entry from 1884: ‘The break with my wife – I don’t know what’s still to come, but it’s complete.’ This was written on the same summer’s day that Sonya was delivered of a twelfth child (of whom nine survived). Three weeks later Tolstoy adds: ‘Till the day of my death she will be a millstone around my neck and the children’s.’

One feels the need to turn to a biography for context, and above all for some consideration of the self-justifying counter-narratives of the marriage that both partners were now urgently constructing and hiding from each other in their diaries, clearly with posterity in mind. A.N. Wilson’s Life will do the job; read side by side the two books provide an extraordinary record of the private turmoil from which great narrative so often springs. Nothing could be more sharply focused and transparent than Tolstoy’s prose, nothing more confused, often grotesque, than his private conduct. The need for the one apparently stems from the distress caused by the other.

It was Lev who changed, plunging the marriage into crisis. Following a deep depression complete with panic attacks in 1869, intensely aware of his mortality and ever obsessed by the idea that his existence must be justified by doing something great and good, he gradually allowed the puritan side of his personality to get the upper hand and, in the late 1870s, underwent a religious conversion. As a consequence, instead of seeming to be a means of reconciling conflicting impulses, marriage began to feel like something that prevented him from following a vocation for celibacy and sanctity. Rather than saving him, he writes, ‘the family is the flesh.’ Nevertheless, he continued to demand his ‘marriage rights’ – and to produce children.

Sonya also changed, in reaction to Lev. If he yearned to be good and understood goodness as renunciation, she needed to be safe and understood safety as possession. Initially, she had feared his carnal side, debauchery, betrayal. The letters show her amazement that, on the contrary, it is his religious vocation that is pulling him away from her. What could be more Christian than a large family, she asks? Wouldn’t it be sinful and even criminal to abandon one’s nearest and dearest? Unsurprisingly, she feels vulnerable, nags, becomes hysterical, speaks of suicide. As a result, he is all the more eager to leave. Sonya’s diary entry for 26 August 1882 reads: ‘For the first time in my life, [Lev] has run off to sleep alone in the study … he shouted at the top of his voice that his dearest wish was to leave his family. I shall carry the memory of that heart-felt, heart-rending cry of his to my grave.’

Circumstances contrived both to exacerbate their differences and render them chronic. As the older children reached adolescence, Sonya was eager to have them properly educated so they could take their place in society. This meant buying a house in Moscow, something she finally persuaded Tolstoy to do in 1881. But, like Levin in Anna Karenina, he despised the frivolities and excess of city life and would often stay in Yasnaya Polyana while she mothered the family in town. Living apart, the two could keep up the marriage their correspondence projected, though Sonya was ‘constantly racking my brains as to how to arrange our lives so that you can bear living in Moscow’.

Visiting the city’s slums on the occasion of a census in 1882, Tolstoy witnessed the disgraceful divide between the rich and the poor. Life in high society, to which his wife was committed, was untenable. One must give away everything and follow Christ. In 1883 he renounced his property – the house in Moscow, the Yasnaya Polyana estate and another huge estate in Samara bought in 1871 – and signed it over to his wife, together, crucially, with the right to publish his books. This reassured her, but of course made her all the more worldly in his eyes; it also meant he hadn’t really given anything up at all, since he continued to enjoy the material benefits of his wealth, not least the numerous domestic staff.

The transfer couldn’t reassure Sonya entirely: the estates were poorly managed and two thirds of Tolstoy’s income came from his novels, which he had ceased to write. Instead, in 1879 he began A Confession, a powerful but grotesquely simplified presentation of his life as a passage from libertinism and intellectual nihilism to conversion, awareness of the moral and spiritual superiority of the peasantry, and commitment, not to Russian Orthodoxy, which was abstruse and self-serving, but to the teachings of the Sermon on the Mount. In 1882, when A Confession was completed and had promptly been banned by the censor, he began What Then Must Be Done?, an account of urban poverty, the inevitability of social catastrophe and the absolute need for the rich and powerful to change their ways.

Sonya copied out these books as she had copied the novels, but without the same enthusiasm. She nevertheless became more involved in the books’ publication, personally visiting various authorities and even the tsar to plead that they not be censored, for then of course they would not provide an income for the family. Her letters oscillate between attempts to remember when all was well between them, and moments of utter exasperation.

I see that you have been staying at Yasnaya not for the sake of your intellectual work, which I prize above everything else in life, but for some sort of Robinson Crusoe game. You … dismissed the cook, who would have been happy to do some work in exchange for a stipend, and from morning to night you engage in inappropriate physical labour … I can only say, ‘Enjoy!’ – and still be upset that such intellectual forces are wasted in chopping wood, putting on the samovar and sewing boots.

In a letter written the same day, Tolstoy tells her: ‘Today I had some black radishes with kvass, country soup and baked turnip.’

Reading Wilson’s biography, drama is to the fore; the assassination of the tsar in 1881 leads Tolstoy to write a bizarre letter to his heir petitioning him to pardon his father’s assassins, which is followed by Sonya’s appalled reaction, concerned that the family would be labelled revolutionaries. Reading the letters themselves, on the other hand, you are aware of an intense domestic life: children’s parties, house decorations, reflections on the marriages of brothers, sisters, cousins and friends, endless illnesses, some life-threatening, moments of happiness and depression, discussions of diet and doctors. It is as if the letters, at this point, amounted to a rearguard action in a losing battle, with just occasional admissions, usually by Sonya, that also read like pathetic appeals: ‘our lives have taken different directions.’ ‘For the first time … I was not happy that you are coming back … you’ll be a living but silent reproach to my life in Moscow.’

Finally, in December 1885, Tolstoy writes a letter that spells things out. After ‘seven or eight years’ of fruitless debate it is clear there can be no harmony between them until she comes round to his way of thinking and gives up ‘the life of our social stratum … all geared to living for one’s self, all built on pride, cruelty, oppression and evil’. There is no question of his changing position, he continues, since his convictions are the result of long reflection that has brought him to ‘the truth’ and the truth is absolute and must be the same for all. However, she and the children ‘have inculcated in yourselves a habit of forgetting, of not seeing, of not understanding, of not admitting the existence of such views’. It is an extremely long, increasingly aggressive letter, ending with the accusation: ‘you are the cause – the unintentional, unwitting cause – of my sufferings … A struggle for death is taking place between us.’ The reader wonders what could possibly follow such a missive but separation and may be surprised to see no mention of it in Sonya’s next letter. Only those who assiduously check the footnotes will realise that it was never sent. Tolstoy remained utterly conflicted. He held these views but couldn’t act on them; life was more complicated than the simple truths he yearned for; this, rather than his wife, was the source of his torment.

As the 1880s progressed, Tolstoy’s obsessions meshed with the political situation. Revolutionaries, anarchists and eccentrics of all kinds flocked to Yasnaya Polyana as disciples to a messiah. Sonya called them the ‘dark ones’, suggesting a struggle for her husband’s soul. Certainly she was jealous. Bolstered by this support, Tolstoy espoused radical causes, did all he could to defend a sect, the Dukhobors, whose members were pacifists who refused conscription. Sonya accuses him of seeking celebrity. ‘You will ruin us all with your provocative articles,’ she wrote. In fact, his fame was spreading faster and further with his social and religious writings than with the novels.

The arrival on the scene of Vladimir Chertkov in October 1883 provided a focus for the marital battle. A handsome, aristocratic evangelical 26 years younger than Tolstoy, Chertkov fell entirely under the writer’s spell. More surprisingly, Tolstoy was besotted with him, spoke of wishing to live with him, wrote him ecstatic letters. Sonya suspected a homosexual interest. Wilson persuasively suggests that the most attractive thing to Tolstoy about such a relationship was that it took him away from sex, not towards it. But when Chertkov launched a press with the aim of distributing cheap editions of Tolstoy’s writings for a huge public, Sonya feared for the children’s inheritance. When he took possession of Tolstoy’s diaries, she suspected he wanted to rob her of her place in history. Her husband must never deny, she told him, the central role she played in his achievements.

More and more, Tolstoy’s conflicting sides were externalised in the figures of wife and disciple (‘They are tearing me apart,’ he would eventually protest), while his children became increasingly confused, drawn this way and that, depending on whether they were staying with their father in the country or their mother in the city. Sonya insists that Lev must not try to convert the girls to vegetarianism; Lev is upset that Sonya is encouraging them to go to balls and entertainments. Tanya, the oldest daughter, who had been on her mother’s side, begins to yearn to be pure enough to marry a wonderful man like Chertkov. And so on.

In 1887 Tolstoy once more resorted to fiction to achieve some kind of synthesis. In The Kreutzer Sonata a sympathetic, neutral narrator on a long train journey hears the confession of a man who shares Tolstoy’s views on sex and society but in a fit of jealousy has murdered his wife. ‘I was wallowing in the slime of debauchery,’ he says of himself before his marriage, ‘and at the same time looking for girls who might be pure enough to be worthy of me!’ He had showed his bride-to-be his diary, he says, ‘So she could get some idea of the sort of life I’d been leading … I remember her horror, despair and perplexity … I could see she was thinking of leaving me. If only she had!’

Bizarrely, Sonya read this novel out loud to the family, rejoicing that Lev was back in the saddle, while Tolstoy himself felt delighted at ‘the recovery of my talent’. In the story, the obsessive husband describes how, producing one child after another, he and his wife came to hate and lust after each other simultaneously. Even in marriage sex was an abomination; chastity was the only hope. Yearning to leave her, he nevertheless became insanely jealous when she took on a handsome violin tutor. Returning unexpectedly from a journey and finding the two playing the ‘Kreutzer’ Sonata late in the evening, convinced they must already be lovers, he stabbed his wife to death, and was acquitted because the jury felt the woman had indeed misbehaved.

It’s a devastatingly unpleasant tale, wonderfully told. The tsar thought it ‘magnificent’. Initially eager to include the book in the Collected Works she was preparing, Sonya was upset when she heard the Moscow gossip – Tolstoy had described his own marriage. To confute the sneerers, she had it put about that the couple still enjoyed marital relations, which of course was part of the problem. A thirteenth and last child was born while the novel was being written. Tolstoy was extremely pleased with the book: his condemnation of sex and society had been powerfully and persuasively expressed, but by a voice that largely disqualifies it and within a narrative frame that suggests the impossibility of ever living according to such views. This was his experience exactly. Chertkov objected that this wasn’t the way to encourage social progress, rather the contrary. Tolstoy might well have pointed out, as he had elsewhere, that novels were not pamphlets and had nothing to do with progress. But of course that was precisely the reason he had abandoned fiction after Anna Karenina. Conflicted as ever, he added an afterword in which, in his own voice, he endorsed his murderer’s condemnations of society and sex. Truth and social change were more important than art.

Just as Tolstoy was finishing The Kreutzer Sonata, Sonya met the composer and pianist Sergei Taneyev, who was 12 years younger than she was. He began to visit the Tolstoys’ house, and played duets and chess with the writer. Some six years later, shortly after the death of their last child, Ivan, aged six, Sonya, deeply depressed, asked Taneyev to become her piano teacher and became infatuated with him. It was as if she had learned from the novel how to keep her husband madly attached to her. Almost seventy now, he was furiously jealous. ‘It is terribly painful and humiliatingly shameful,’ he writes to her, ‘that a complete stranger, whom we don’t need at all and is of no interest is … poisoning the last years … of our life … just when we were drawing closer and closer together, despite everything that could divide us.’

Clearly this tangle could only get worse as the children threw themselves into the fray, as Tolstoy’s increasing celebrity attracted more disciples (excommunication in 1901 only increased his notoriety), as the political situation became intensely polarised and many of his supporters were imprisoned or exiled (justifying Sonya’s fears), and as Tolstoy himself, in old age, began to make one will after another, publicly or in secret, benefiting now the propagandists who wanted control of his writing, now his family. Many of the later letters are quite frantic, with Sonya attacking Chertkov in violent terms and demanding that Lev take back unpleasant things he has written about her in his diary (‘it enhances your glory to be a victim, [but have you ever considered] how that will ruin me?’). He offers to stop seeing Chertkov then withdraws the offer. ‘You have been caressing me with one hand while showing me a knife with the other,’ Sonya protests. Yet still she is proofreading his last novel, Resurrection, and arranging for his papers to be moved to Moscow’s Historical Museum. Still the two address each other as ‘my dove’, ‘my dear friend’; still they exchange views on the children’s marriages and careers, publishing problems, health, the weather. ‘My dove, stop the torture,’ Lev pleads. ‘My one hope,’ Sonya despairs, ‘is that you will give me for safekeeping the paper and key to the safety deposit box at the bank. Give them to me, my dove …’

Attempts to draw a line under the relationship, whether by departure or, on her part, suicide, grew ever more frequent. When finally, in November 1910, aged 82, Tolstoy escaped from Yasnaya Polyana in the night while his wife was sleeping, it is doubtful he would have managed to stay away for long had not pneumonia caught up with him 12 days later at the Astapovo railway station, 150 miles away. Sonya was pacing the platform when he died, kept from him by her overwrought children who still hoped that without the excitement of confronting her he might recover.

Reading about Tolstoy, his work, his philosophy, his marriage, the heated division over who was to blame for the unedifying melodrama of the later years, one is conscious of the overwhelming consensus that it is a terrible shame he largely abandoned fiction after Anna Karenina. In this sense critics and biographers share Sonya’s point of view, which was also that of polite society. Yet aside from his extreme antipathy to sex, most of the principles Tolstoy dedicated himself to promoting – pacifism, equality of education, freedom of speech – are widely shared today, and shared particularly by the literature-reading public. The most difficult thing to come to terms with, then, is that Tolstoy did not believe, as Victor Hugo more conveniently did, that a commitment to social or spiritual progress could be achieved through huge novels earning vast advances and aimed at entertaining the middle classes. If anything, Tolstoy had come to see literature, with its presentation of life as insoluble conundrum, as contributing to inertia, not to change.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.