It seems eccentric to say it of a person richer than the queen, but J.K. Rowling is, I think, undervalued. Or rather, she gets credit for the less important things, for being a marketing phenomenon whose books have sold more than 400 million copies, and not for the painstaking intricacy of the texts themselves. In the nine years that I’ve been writing children’s fiction, one of the questions I’ve been most often asked is ‘Are they any good, the Potter books?’ – a question which, like the Latin prefix num, anticipates the answer ‘no’.

A lot of their power comes from appealing to the fairy-tale desire of every child to believe that they are secretly special, the Chosen One. An ignoble plot-engine, you could say, though one that has been deployed by narratives from King Arthur to Star Wars. Freud called it the ‘family romance’. Stylistically, the books sprawl; Rowling’s prose is laden with adverbs and adjectives, and on any one page characters might speak ‘sharply’, ‘curiously’, ‘impatiently’ and ‘suddenly’. (The same is true of Tolkien.) They are not texts that traffic in ambiguity; we are rarely left in doubt as to the precise emotion of any character in the room. (The same is true of Dickens.)

Rowling revels, too, in the humour of bodily excretions. Her books deal with ambition and corruption, power and death, but she is silly as often as she is wise. Rowling is a writer who has looked into the hearts of children, and seen immense moral seriousness compounded with frenetic energy and a measure of lunacy. Because her evocation of the Christ narrative is mixed in with jokes about troll snot, it is possible to dismiss the books as a little thin, a little cheap (this would be a mistake).

It is possible too that the Harry Potter films, as they grew larger, made the books smaller. The eight movies based on the seven books grossed $7.7 billion; and with that came the merchandise, and the use of Harry’s face to launch a thousand lunchboxes, and the brittle quality that pervades anything once it becomes a brand. The Potter films themselves were in many ways a marvel: the special effects were remarkable, the adult cast a dream, and they have heart and wit on their side. Produced by David Heyman, who went on with Rosie Alison to make the hit Paddington movies, they raised the bar for live-action family entertainment. But they are big-budget motion pictures: tap them and they ring like money. Great children’s fiction isn’t slick; the film studio’s imperatives of mass audiences and shareholders erode at the difficult edges of a work.

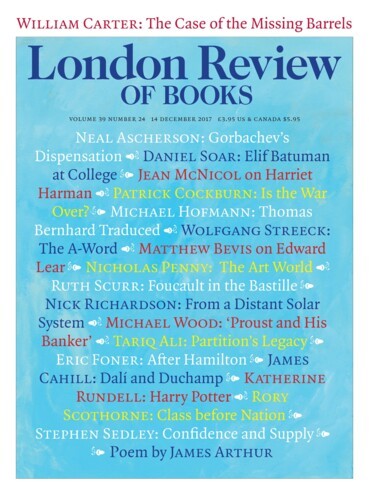

The current exhibition at the British Library, Harry Potter: A History of Magic (until 28 February), situates Rowling in a European tradition of accounts of alchemy, botany, astrology and witchcraft, and in doing so, reroots Harry Potter in a history of manuscripts and books. The show underscores the textuality of Harry Potter’s birth, makes clear that he rose from heaps of scrap paper and memories of other, far older books. It reminds visitors that the world which exists behind the eyes has movement and textures all of its own; it is coloured by the individual shades of each reader’s imagination, and is a phenomenon that film, for all its scope, can’t mimic. It does not claim that Rowling had knowledge of all the texts on display; rather, that she drew from their world. It offers her a place in that lineage.

The Potter books lend themselves to a curated exhibition in a way other stories might not. Child readers are collectors of facts, covetous of minutiae, and Rowling’s world offers a largesse of such detail. As a 12-year-old I could have told you all sorts of details about the Potter world – the complete first-year reading list, the cost in galleons of Harry’s owl – that I could not now tell you about my own books. This collector’s mindset is a quality the exhibition plays to; offering a wealth of variety, gathered up from across history and the BL’s collection, and laid out in dimly lit rooms. I went twice: both times children ran, uttering muffled screams of joy, from case to case.

The exhibition opens with a note from Alice Newton, the eight-year-old daughter of Bloomsbury’s chief executive. Alice’s review is said to be what prompted Nigel Newton to buy the first Harry Potter book: written on a scrap of paper the size of a large matchbox, it reads: ‘The excitement in this book made me feel warm inside. I think it is possibly one of the best books an 8/9 year old could read.’ It was valuable advice: the franchise, including the Fantastic Beasts films and the theme parks, is worth an estimated $25 billion.

The first room is dominated by the Ripley Scroll. It is an astonishingly lovely thing; a 16th-century copy of an illustrated manuscript by the English alchemist George Ripley, which gives instructions on how to make the Philosopher’s Stone. It is nearly six metres long when fully unrolled. Some of the images are purposefully obscure, to protect the secrets of alchemy (rather missing the point of an instruction manual). One image, of a red lion meeting a green lion, is thought to depict sulphur and mercury being mixed in a chemical bath, but could be taken as other things too. (Harry’s school house, Gryffindor, has a lion as its symbol.)

In the same room is Bald’s Leechbook, a tenth-century manuscript open to the page detailing ‘potions and leechdoms against poison’. Some of Bald’s cures were effective – one has been recently found to combat the MRSA bacterium – while others are less medically authoritative. One, in the Cockaygne translation of 1864, reads: ‘against a woman’s chatter: taste at night fasting a root of radish, that day the chatter cannot harm thee.’ There is, too, a bezoar, a stone taken from the stomach of an animal, in a gold filigree case from the 17th century. Harry saves his friend Ron from poisoning by making him swallow a bezoar, a remedy that remained popular into the 18th century despite the fact that in 1657 the surgeon Ambroise Paré tested the properties of the stone and found them wanting. He did this by poisoning and then attempting to heal a cook who’d been condemned to death for stealing the king’s silver, on the understanding that if the man survived his life would be spared. The cook died gruesomely seven hours later.

Scattered alongside incunabula and illuminated texts are images by Jim Kay, the artist behind the new illustrated Potter books, whose work is a delight, ranging from sketches of Harry to oil paintings of the Hogwarts teachers in the style of Renaissance portraiture. Kay’s sketches act as a counterpoint to the archive; his line drawing of a magical mandrake (a screaming baby in the books) hangs above a 15th-century European manuscript, which shows the mandrake root as a middle-aged man with knee-length hair and a large penis.

Divination comes in the middle of the exhibition, which is fitting because prophecy is at the heart of the books. The exhibition has a copy of the 18th-century Wonders!!! Past, Present and to Come: Being the Strange Prophecies and Uncommon Predictions of the Famous Mother Shipton. Mother Shipton, the famously ugly witch who is said to have prophesied the fall of Cardinal Wolsey in 1530, adorns the frontispiece, with a chin so curved and a nose so hooked they nearly meet in the middle. Also attracting clamorous crowds was The Book of Solomon Called the Key of Knowledge, a 17th-century English version of the grimoire, opened to a chapter entitled ‘Howe experiments to be invisible must be prepared’ with an incantation in red ink. I tried (and failed). Possibly my pronunciation was off.

Alongside the illuminated medieval manuscripts are Rowling’s own early handwritten drafts. Rowling has sometimes been read with the benevolent misogyny which aligns male writing with intellect and knowingness and female writing with intuition; this exhibition offers a welcome corrective. In laying out the sheer work, the research and forethought, that went into the creation of the books’ complicated plots, it shows that her novels were built and not born, constructed from experiments and sparks, errors and false starts: a manuscript of an alternative opening has a giant called Hagrid visiting a muggle minister called Fudge to try to explain about a red-eyed dwarf-like creature. There is the simple pleasure, too, of seeing something very familiar in its ungainly, fledgling state. On a manuscript of The Half-Blood Prince, Rowling’s editor has struck a line through the word ‘dammit’ and written ‘typical’. A comment in the margin reads: ‘at this stage the swearing would be much stronger.’

In the final room there is a formidable hand-drawn chart from 2001, sketching out The Order of the Phoenix two years before its publication. The headings are ‘day, month, plot, prophesy, Cho/Ginny, D.A., O.P., Harry/Snape/Father, Hagrid + Grawp’. Rowling’s note for the exhibition adds: ‘I had plotted the remainder of the series in a broad sense by the time I finished Philosopher’s Stone. I knew roughly who was going to die and where, and that the story would culminate in the Battle for Hogwarts.’ Elsewhere she says: ‘I try to be meticulous and make sure that everything operates according to laws, however off, so that everyone understands exactly how and why.’ Rowling knows that children demand consistency, punctiliousness, reality within the limits of the imaginary world. That is her great achievement; for all her snot jokes, she takes the hearts and hopes of children seriously. The exhibition lays out the ways Rowling mined the history of magic, but stayed within the laws of her own making. When she built Hogwarts she created a place for children to rest in: a school large enough to hold the hundreds of millions who would come.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.