On 19 June 1790 the Prussian nobleman Jean-Baptiste du Val-de-Grâce, baron de Cloots, appeared at the bar of the French National Assembly. Five years earlier, he had left Paris in disgust at monarchical despotism, vowing not to return until the Bastille – its most notorious symbol – had fallen. Now he led a delegation of foreigners pleading the right to participate in the Fête de la Fédération, to commemorate the first anniversary of the fortress’s capture by the people of Paris. According to the minutes of the Assembly, his 36-man delegation included ‘Arabs, Chaldaeans, Prussians, Poles, English, Swiss, Germans, Dutchmen, Swedes, Italians, Spaniards, Americans, Indians, Syrians, Brabaçons, Liégeois, Avignonnais, Genevans’. Moved by their entreaties, the deputies not only reserved a special place for foreigners at the celebrations on 14 July, but concluded the session by pronouncing the abolition of noble titles. The former baron Cloots adopted the name Anacharsis, a homage to the philosopher-hero of Jean-Jacques Barthélemy’s bestselling novel about the defence of ancient Greek liberty.

On 26 August 1792, two weeks after the overthrow of Louis XVI, Cloots was one of 18 foreigners accorded citizenship by the new republic; in September he was elected to the successor to the National Assembly, the Convention. He let himself be known as the ‘orator of the human race’ and dreamed of a world in which all states would be abolished in favour of a single global republic. But such cosmopolitan fantasies soon evaporated as the revolutionary government turned against those to whom it had previously offered asylum. By 1793, with France at war against a coalition of European powers, non-French nationals were hounded, imprisoned and expelled. In the spring of 1794 Robespierre stormed into the Convention and denounced Cloots for his links to the Vandenyver banking family, who were accused of distributing British gold in France. ‘Can we regard a German baron as a patriot? Can we regard a man with an income of more than a thousand livres as a sans-culotte?’ Cloots’s origins had caught up with him and he was guillotined before a large and spiteful crowd.

What happened to Cloots exemplifies some of the elements of revolutionary politics: the capacity for social reinvention, as well as its dangers; the quicksilver mutation of policies into their opposites; and the ineluctable gobbling-up of radicals by insatiable Mother Revolution. Cloots’s story also captures the ecstatic reaction to the revolution outside France’s borders. Early admirers across the Rhine abstracted the struggles for rights and recognition into a clash of warring concepts resulting in the painful birth of epochal truths (what Hegel called ‘a glorious mental dawn’). Sloughing off the muck and the gore, intellectuals made the revolution the hinge of a new philosophy of history. Nietzsche relished the irony that the revolution – ‘that gruesome and, closely considered, superfluous farce’ – had become almost unrecognisable, wrapped up in layers of excitable commentary: ‘Noble and enthusiastic spectators all over Europe interpreted from a distance their own indignations and raptures so long and so passionately that the text disappeared beneath the interpretation.’

By contrast, the great merit of Peter McPhee’s new synthesis is the weight it gives to the earthy, even mundane, aspects of revolutionary experience. It examines 1789 from the peripheries, rather than Paris, as seen through the eyes of the menu peuple, rather than from the heights of the Mountain, those radical deputies who sat on the highest benches of the Legislative Assembly. Neither the provincial geography of the book, nor its broad conclusions, would have displeased Georges Lefebvre, the interwar pioneer of history from below. What is lost in terms of the familiar drama of the revolution is gained in the portrayal of innumerable ordinary citizens who were obliged to pick sides and take momentous decisions. The principles of 1789 as proclaimed in the capital had to be embedded in thousands of villages and communes across France, a process commemorated in the planting of liberty trees, the naming of babies (‘Mucius Scaevola’, ‘Faisceau Pique Terreur’ and ‘Fumier’ – or ‘dung heap’, an eccentric emblem of regeneration) and the erection of altars to the fatherland (only one still stands, a dour column in Thionville on the Moselle).

However geographically and culturally remote they were from the court at Versailles, the subjects of Louis XVI felt they had been invited to become involved in national politics. By 1789 the king was bankrupt, and the normal avenues of reform exhausted; with the crown and the nobility at loggerheads, the state’s insolvency could not be fixed by fiscal austerity or constitutional tinkering. Instead the king resorted to convening the ostensibly extinct Estates General, and asked every commune in France to elect representatives and draw up registers of grievances to provide some framework for reform. But once this process of consultation had begun, it proved impossible to dampen popular expectations of sweeping change. The storming of the Bastille, and the creation of the National Assembly, seemed to legitimate acts of defiance elsewhere in the country. In December 1789, ‘wild federations’ spontaneously assembled in the south-west, around Montauban and Rodez, to protest against paying harvest dues. The peasants marauded through nearby villages, trashing weathercocks as symbols of seigneurial authority, tossing church pews onto a bonfire and dancing around a maypole. Their slogans included ‘Woe to he who pays his rent!’ and ‘We don’t need a bourgeois or a gentleman any more!’ The old bonds of deference were in tatters. In 1790 the baron de Bouisse was horrified to observe the sudden change that had come over the once peaceful tenants of the village of Fraïsse near Narbonne, whom he used to dote on as his children: ‘All I hear now is corvée, lanternes, démocrates, aristocrates, words which for me are barbaric and I can’t use … the former vassals believe themselves to be more powerful than kings.’

The cacophony of voices in McPhee’s book recalls the work of Richard Cobb; it shows a similar sensitivity to regional variation and delight in anarchic individualism. McPhee offsets popular devotion to the revolution with evidence of apathy, frustration and profanity. ‘Vive le roi! The republic can get fucked,’ one woman screamed in front of the Hôtel de Ville, where executions took place at the height of the Terror. ‘I shit on the nation!’ But diaries and memoirs from these years illustrate the exhilaration felt in all social groups at the unfolding spectacle. Those who lived through the revolution, whether as friend or foe, knew they belonged to a unique historical moment. Marianne Charpentier, an artisan in Orléans, intended the diary she kept between 1788 and 1804 to be read by future generations. She wanted to show them what ‘their ancestors had suffered during the revolution of that century’, and hoped that ‘God would show the grace to allow you to pass through yours more easily’.

In contrast to interpretations that stress the importance of discourse and ideology, McPhee never loses sight of the practical inducements and calculations that structured political action. In the early years of the revolution, wealth, which was synonymous with independence, was a precondition for ‘active’ citizenship. The capacity to vote in elections, hold public office and serve in the national guard depended on property ownership. The universalism of the Declaration of the Rights of Man co-existed with toleration of colonial slavery: the planters’ claims over their human chattels were viewed as sacred by revolutionary law. And yet in its opening months, the National Assembly had demonstrated the way certain inalienable rights of ownership could be abrogated on grounds of expediency. On 4 August 1789, aware that rural France was in disarray, the deputies voted to renounce feudal rights, such as the dominion over harvests, hunting grounds, forced labour and wine presses (with the caveat that freed peasants stump up compensation). This bonfire of the privileges divided revolutionary time into ‘now’ and ‘then’, pitting the virtuous present against the wicked Ancien Régime. A similar blend of high principle and pragmatism resurfaced that autumn, when the assets of the Church were confiscated in order to plug the hole in the national debt. As many as one person in eight seized the chance to buy former church land, though wealthier purchasers predominated. The release from tithes, feudal dues and seigneurial courts was welcomed in many rural areas, and over the long term French peasants grew fatter and lived longer now that they could hold on to more of their produce.

Having secured these gains, the rural poor were determined to resist backsliding. ‘Of all the passions, hatred of the Ancien Régime was paramount,’ Tocqueville wrote. ‘No matter how much people suffered and trembled, they always considered the hazards of a return to the old order worse than all the pains and vicissitudes of their day and age.’ In many parts of central and southern France, special hatred was reserved for the clergy, those calotinocrates who for generations had leeched off the farmer’s crops, perverted his wife and misled his children. The stubborn refusal of more than a third of priests to swear allegiance to the Civil Constitution of the Clergy in 1790 confirmed their status as the enemy within. One refractory priest at Troyes, François-Pierre Juliot, complained in 1790 that his parishioners had commandeered the high altar as a dining table and urinated in the choir and the sanctuary in protest at his non-compliance with the oath. Such carnivalesque blasphemies prefigured the ritualised cruelties inflicted on the bodies of non-juring priests, whose obedience to the pope classed them as agents of subversion. Probably 25 per cent of the clergy had the sense to emigrate in the revolutionary decade, while three thousand more, around 2 per cent of the total, met violent, often gruesome, deaths.

But in abolishing feudal property, the revolutionaries also obscured the true sources of social power. Under the old regime, the ruling classes were marked out through their decorations, pomp and special exemptions. In the egalitarian society constructed after 1789, in which all men (though not women) were citoyens, and sartorial distinctions were ditched, the elite blended imperceptibly with the masses. Moreover, as Marx recognised, and as William Reddy elaborated in Money and Liberty in Modern Europe (1987), by legislating that feudal rights could be redeemed through cash compensation, the revolutionaries consecrated money as the universal equaliser. The trappings that made wealth legible had vanished, while its power remained, covered over and denied. One system of oppression had been overthrown and another had silently been put in its place, one that still generated relationships of dependence but was far harder to uproot. Even in a society founded on universal and transparent maxims, the workings of power remained mysterious, providing fertile ground for belief in cabals and subterranean plots.

This uncertainty encouraged the scrutiny and unmasking of false patriots, those who dissembled virtue in public while scheming and profiteering in private. From its beginnings the revolution seemed liable to betrayal from people such as Mirabeau (secretly conniving with foreign courts) and Lafayette (who fired on petitioners) – as well as from Louis XVI, who perjured his oath to uphold the constitution by making a doomed dash for the border before being arrested and returned to Paris. Conspiracy theories gained disturbing credibility as émigrés massed on France’s borders. Shortly after the king’s flight in June 1791, Pierre-François Lepoutre, a prosperous farmer near Lille, warned his wife that ‘war is inevitable, that the Prince de Condé together with the Comte d’Artois are going to descend on France with an army of about five thousand men in black clothes made from the cassocks of non-juring clergy and studded with death’s heads.’ These were not idle fears. In April 1792, an increasingly desperate Louis XVI gambled on war with Austria, calculating that victory might save his reputation and defeat might bring liberation by his wife’s Habsburg relatives. The dreaded alliance between France’s internal and external enemies seemed to be taking shape.

Distinctions between active and passive citizens, male and female, even slave and free, melted away in the fires of war. ‘Our fathers, husbands and sons may perhaps be the victims of our enemies’ fury,’ a petition from the Société Fraternelle des Minimes declared, signed by three hundred women. ‘Could we be forbidden the sweetness of avenging them or dying at their sides?’ The axioms of 1789 had to be stretched or reconfigured to fit the mounting of a national defence. Advocates of free trade found themselves voting for the imposition of price controls. Attempts to collect compensation for the abolition of feudal dues had to be abandoned because of widespread non-compliance. Most dramatically, the rebellion that erupted on Saint-Domingue saw enslaved Africans appropriate the vocabulary of the rights of man. In the scramble to protect the lucrative sugar islands from British and Spanish encroachment, the French official Légér-Félicité Sonthonax offered emancipation to any slaves who would fight under the tricolore, anticipating by six months the formal abolition of slavery by the Convention in February 1794. Time and again, political thinking lagged behind changes on the ground.

After the overthrow of the monarchy on 10 August 1792, the nascent republic drew its legitimacy and dynamism from popular participation. Six million men were enfranchised by the 1793 constitution – it would take Britain until the Third Reform Act in 1884-85 to hit comparable proportions – and the formal mechanisms of voting were supplemented through petitions, demonstrations, attendance at clubs and pseudo-sacred festivals. There was a remarkable levelling in the composition of local government: in Paris, a third of the councillors elected to the Commune came from the lower classes, as did four-fifths of those who sat on the revolutionary committees in each section of the city. The priorities – and prejudices – of artisans were brought to the heart of government. Demands for the ‘right to subsistence’ and the stern repression of counter-revolutionaries were accompanied by a profound suspicion of the swindles effected by international finance. The accusations brought against Danton and the journalist Jacques Hébert, like those against Anacharsis Cloots, turned on their consorting with foreign bankers – the Englishman John Ker, the Dutch banker Jean Conrad de Kock, the Belgian Charles Proli, the Moravian Frey brothers, the Spaniard André-Marie Guzman – and speculating in global markets. The sans-culottes distrusted any political behaviour whose workings were not local and tangible.

‘The Republic of 1793 was a demanding regime,’ McPhee acknowledges. ‘The language of patriotism, virtue and citizenship was mixed with one of sacrifice, requisitioning and conscription.’ This is putting it mildly. The order for a levée en masse in the summer of 1793, which saw the French army balloon to 700,000 men, required an ever greater blood tribute of sons to defend the patrie (not to mention crops to feed them). The crisis in the luxury trades caused unemployment in the towns, while the British blockade and the chaos in the Caribbean spelled ruin for Atlantic ports. The assault on church organisations deprived the destitute of a key source of charity; although the Jacobins pioneered the idea of welfare as a state responsibility, practice fell miserably short of the rhetoric. The same was true of education: the principle of free, compulsory, non-denominational schooling set out in the 1793 Bouquier law did not mean much in Clermont-Ferrand, where only 120 children in a population of twenty thousand went to school. Any balance sheet of winners and losers from the revolution has to reckon with the appalling levels of privation. It was in these unforgiving circumstances that emerging democratic practices were thrashed out.

It would be wrong to disregard the aspirations of the revolutionaries, which were even more remarkable in light of the abundant evidence for the obstinately unregenerate nature of French society. But we should remember that many of the ‘modern’ ideas espoused during the revolution – natural rights, national sovereignty, meritocracy, feminism, even anti-imperialism – had to be realised in a premodern environment of scarcity, bigotry and hatred. The deputies in the Convention dreamed of Sparta and Rome, but the polis they served was constituted of citizens shaped by the inequalities and animosities of the Ancien Régime. The central task of the emergency dictatorship set up in 1793, the Committee of Public Safety, was to save the revolution and preserve the integrity of France, though the methods they deployed to prosecute the war drove the provinces into outright rebellion. The Terror, which began with vicious popular reprisals against perceived wartime enemies in 1792, was transformed a year later into an instrument of government. Terror was inseparable from the pacification of revolts in the southern cities – the vengeful deputy Georges Couthon wanted Lyon emptied of its treacherous inhabitants and razed to the ground; Marseille was renamed ‘Sans-Nom’ after an insurrection – as well as the slaughter of approximately 200,000 Catholic and royalist rebels in the Vendée. These were civil wars, stoked by religious fury and local hatreds, in which the authority of the Convention was shaky at best. The shredding of legal protections, and the efficiency of the guillotine, were chillingly simplistic solutions for complex challenges that the Jacobins in Paris could neither fully control nor comprehend.

And yet, against the odds, the centre did hold. By the summer of 1794 the Austrian and Prussian invaders had been repelled and ‘la grande nation’ was on the offensive. Now that his sanguinary ministry was no longer required, the Convention could finally turn against Robespierre, scapegoating him and his associates for the excesses of the past two years. That the Thermidor coup was the brainchild of ardent terroristes was only one among several bitter ironies in this period of transition. The vicious reprisals meted out to former Jacobins in the Midi (demonised as cannibals and ‘buveurs de sang’) claimed thirty thousand victims, making the White Terror almost as destructive as its Jacobin twin. The sans-culottes who had been the shock troops of the radical republic saw their clubs smashed and their neighbourhoods redrawn. Food shortages, rampant inflation and a pitiless winter conspired to exacerbate popular suffering. The capital’s tollgates, ripped down in 1789, were up and running again by 1798. Slaves who had fought for their freedom were coerced into labouring on plantations under the logic of ‘republican racism’, in which the full exercise of citizens’ rights was indefinitely deferred, until such a time as these ‘brutalised’ men might deserve it.

In hindsight, the Thermidorean period, in which power was taken away from the street and the village and conferred on propertied stakeholders, bureaucrats and scientific experts, was a foundational moment for liberalism in the 19th century and beyond. The disintegration of the Ancien Régime in 1789 is no more compelling or relevant a narrative than the reconstruction of a regime of inequality after 1795. ‘We should be governed by the best among us; the best are the most highly educated, and those with the greatest interest in upholding the laws,’ Boissy d’Anglas announced unashamedly in June 1795. Jean-Denis Lanjuinais agreed that it would be as absurd to extend political rights to unpropertied men in thrall to ‘crass ignorance, the basest greed and crapulous drunkenness’ as it would be to enfranchise ‘the mad, idiots, women, children and foreigners’. In the five-man executive of the Directory (1795-99) they proceeded to construct a ‘liberal authoritarian’ system, based on a restricted franchise, conquest and plunder abroad and an ever vigilant security apparatus. The participatory aspects of republicanism were so hollowed out through electoral manipulation and military intimidation that few were willing to defend the regime when it was cannibalised by its erstwhile defender, the army, in 1799.

Elevated to first consul, Napoleon ended the cycle of revolutionary instability, stamping out remaining pockets of rural brigandage, and allowing the exiled nobility and ravaged Church to resume some of their former standing. At the same time he exported the vortex across the continent, where it swallowed up millions more lives. ‘I have closed the gaping abyss of anarchy,’ he later bragged in exile on St Helena, ‘and I have unscrambled chaos.’ Reading McPhee’s book, it is hard to blame the common people for going along with the dismantling of the democratic experiment. Through disobedience and ingenuity they had already achieved great things, often pushing their representatives further than they had ever intended to go: the material and psychological underpinnings of the old regime were exploded; the authority of king, lord and bishop would never be the same; and the rights and lands won in 1789 could not be taken away. But ordinary French farmers and artisans also knew the enormous burdens these advances had entailed. In the short term at least few mourned the freezing-over of the revolution.

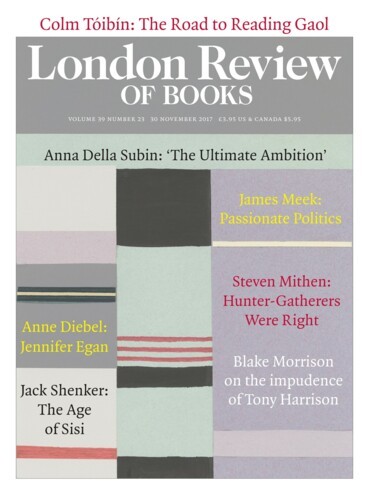

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.