Two summers ago , 2015, it rained a lot in the West Midlands. A bit glum at first, I lay in the garden when I could, with my pile of madeleines – paper lieux de mémoire, novels. Like many of the old new universities, Warwick was revving up for its 50th-anniversary celebrations. The contribution of my former department to the general gaiety was to be a talk by Margaret Drabble, on the topic of young women at university in the 1960s and 1970s. I was dun gone, as we say in the trade, pensioned off, but reeled in for a last duty. ‘Or as warm-up woman,’ I said in the same breath as ‘I’d be delighted. I’ve read all her novels. I love them.’ They’ve been the Chorus to my generation, telling you what is happening in your life. Or I said something like that. And then: But no one in her novels is at university in the 1960s and 1970s; they’re there in the 1950s! Well, we are all just going to have to cope with that, was the reply.

Something strange and wonderful happens if you read every novel Drabble wrote between 1963 and 1980, in sequence, one hard on the heels of another, with your notebook page firmly headed ‘Young Women at University’. First, you realise that the novels themselves will provide you with the rhetorical solution to the problem of addressing a heterogeneous audience, to which you have to say something historical about higher education; something dull on the way to getting what they’re here for: Drabble. Frances Wingate, the protagonist of The Realms of Gold (1975), is at a party. ‘“Isn’t your father vice-chancellor of Wolverton University?” asked the woman from the Department of the Environment, and initiated a long conversation about new British universities … Frances struggled, and then gave in. It was going to be boring, after all.’

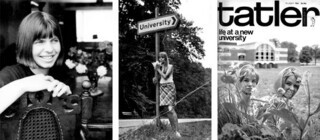

In Students: A Gendered History (2005) Carol Dyhouse says of this photograph on the cover of the 1966 Warwick Students’ Handbook: ‘A wistful-looking blonde in a mini-skirt [is] leaning against a signpost in a rural setting … marked simply “university” … the dollybird was effectively part of the branding image of the new university.’ But this isn’t a rural setting: it’s the corner of Kenilworth Road and Gibbet Hill Road to the south of the university, and the lady sitting on the bench in the background must be waiting for a bus to take her into Coventry. Maybe she’s off shopping, or going to Coventry Market. We’re in a complex, long-established, urban economy here. And the sign isn’t to some vague place called ‘university’. It’s a local road sign, put up by the Ministry of Transport and Warwickshire County Council, designating an actual place: the University of Warwick.

I think there’s room for speculating about why the – winsome, I’d say, rather than wistful – blonde is contemplating a feather duster (if that’s what it is). ‘I felt doomed to defeat,’ Sarah, Louise’s more academic sister, says in Drabble’s first novel, A Summer Bird-Cage (1963). ‘I felt all women were doomed. Louise thought she wasn’t but she was. It would get her in the end, some version of it.’ Is the young woman having a moment of reflective irony because she has escaped a woman’s lot – of dusting and getting dinner on the table? ‘What was wrong with me,’ the unhappily married Emma wonders in Drabble’s second novel, The Garrick Year (1964). ‘What had happened to me, that I, who had seemed cut out for some extremity or other, should be here now bending over a washing machine to pick out a button or two and some bits of soggy wet cotton? … They would not think much of me now, I thought, if they could see me, those Marxists in Rome, historians and photographers in Hampstead, those undergraduates, in two universities.’ I do have a very dim memory of feather dusters being a fashion accessory circa 1965 – it went along with the feather boa craze – for I had seen them at parties long before I saw this picture. I was a young woman at a new university in the 1960s too.

I spent weeks thinking about the wistful blonde’s hair, how she must have attempted a straight, thick, shiny wedge, like best friend Clelia’s in Jerusalem the Golden (1967), ‘a solid heavy piece, straight-edged, stopping sharply midway between chin and shoulder … it had a weight that made it look as though it were well cut.’ From my very first reading of Margaret Drabble’s novels I noticed that all her heroines who had been to university had hair like this –with the interesting exception of Jerusalem’s Clara Maugham from Up North and uncertain class status, whose hair we never find out about. My hair was fine and mousy and fluffy and frizzy. You could do something about it, as I did, by ironing it (really, with an iron in those pre-straightener days) every morning between 1963 and 1968. There was the option of simply not caring, like Rose Vassiliou in The Needle’s Eye (1972). She hasn’t been to university, gives her inherited wealth away out of goodness and lack of self-regard, and doesn’t give a toss about her frizz. But I did care, and that Warwick girl cared enough to straighten hers. Not all the styling advice in the world, not even from Vogue, will ever persuade me not to straighten mine.

The girl is there, at the crossroads, under the road sign, because of the Robbins Report. That’s the historical story you need to know to interpret her presence. The Robbins Report was the result of the deliberations of the Committee on Higher Education, chaired by Lord Robbins, which sat between 1961 and 1963. The report, published in 1963, recommended that ‘enough places should be provided to allow the proportion of qualified school leavers who enter universities to be increased as soon as practicable.’ The committee also recommended ‘the foundation of six new universities’ to accommodate a vastly increased number of students. Warwick was one of them. According to Robbins, there were 118,400 full-time students in British universities in 1962-63. Committee members looked ahead to 1970-71 when, they estimated, 344,000 full-time places would be needed, rising to 558,000 in 1980-81.

Scholars – historians, sociologists – have been picking away at the Robbins Report since 1963, uncovering the narratives of class and gender hidden away in its appendices, or concealed in the deep structure of paragraph 50, ‘women in higher education’, in which it was reported that in 1962-63, only 7.3 per cent of the women qualified to do so entered full-time higher education, compared with 9.8 per cent of men. Which doesn’t sound so bad, historically speaking. But according to Dyhouse, the proportion of women in the undergraduate population peaked in the late 1920s. Then it declined and remained at around 23 per cent until the 1960s, reaching 28 per cent – no higher than in the 1920s – in 1968. The number of women undergraduates then rose slowly to reach 38 per cent in 1980. In 2012-13, 56 per cent of students in higher education were female.

The most revealing element of Dyhouse’s work is her uncovering of the little-told story of women in teacher training from 1950 to 1980. To understand more about young women in higher education during these years, we need to know about the training colleges (later, university departments of education). Their postwar expansion was truly dramatic: in 1939, 13,000 students were in training; in 1964, there were 111,000. In 1960 the two-year teaching certificate was replaced by a three-year course. It had less status than a university degree, but students taking that three-year course are included in all the figures given above. In the 1960s, young women were 25 per cent of the university population, and 70 per cent of the teacher training population. Colleges of education were cheap to fund and to attend; they offered a broad curriculum of the liberal arts kind. Possibly, they appealed to women who were less attracted to the specialised honours degree courses in the universities; and anyway, much of the expansion in universities after the war was in science and technology rather than in the arts and social studies, which women applicants were assumed to prefer. The ‘new world for women’ ushered in by Robbins was inhabited by a very large number of students in colleges of education and university education departments. To them could be added scholarship-girl university graduates like Clara in Jerusalem the Golden. In the late 1960s she registers for what would later be called the pgce – a teaching certificate – which is bang on the statistical trend for her era (and for the life story she is given).

I have had so very many of my personal historical myths undone – deconstructed – by a proper reading of Robbins and the commentary on it. It’s not exactly that I ever thought ‘I’m here – at university – because of Lord Robbins’; but I did have quite an elaborate Robbins story-of-the-self that turns out to be completely erroneous. I thought for fifty years that Robbins did away with Latin as a university entrance requirement. I reasoned that my girls’ grammar school sent three girls to university in 1964, and 17 in 1965 (when I went to Sussex) because you no longer needed a Latin O-level to get in. The truth of the matter is that Latin gradually disappeared as an entrance qualification in the redbrick universities between about 1950 and 1970, and the new universities never made it an entry requirement. The process by which I constructed this myth is probably not very interesting to anyone but me, but I know I ended up at university partly because of a 1963 photograph of the Jay twins, ‘Sussex students and daughters of the then Labour cabinet minister Douglas Jay … sliding down the library steps in their Courrèges boots and mini-skirts’, as the University of Sussex bulletin put it decades later.

It may well be that my mother saw the issue of the Tatler featuring the twins: she was a manicurist working in classy places in the West End which would have provided all the glossies for their clients. But she really wouldn’t have gone for the Jay twins’ style here: the white lipstick! the headscarves! – too much like a hybrid of county lady and Mandy Rice-Davies (she did do Rice-Davies’s nails). But she was very taken by the library-steps photograph from the Sunday Times Colour Supplement, which I remember as if it were still before my eyes. In the kitchen, Streatham Hill; must have been autumn 1963. The Jay twins’ style had moved on: they looked lovely, and their hair was right and the mini-skirts fabulous. Much more age-appropriate (I can’t channel my mother here so I’m not sure what she actually said). The idea – somehow – emerged that I could, would, go to university, not just any old university, but to the University of Sussex, that it was just an ordinary thing to do. And I did. And it was.

And if you look behind the white-lipsticked ones on the Tatler cover, you see the Sussex Students’ Union Building where, in the autumn of 1967, the beginning of my third year, I read my first Drabble novel. I was waiting for someone and I remember clearly the passage of The Garrick Year I was on, when whoever it was arrived. Emma, recently graduated and recently married, is with her husband and their little girl, Flora, on the train to Hereford, where David has been engaged for the season at the newly opened Garrick Theatre:

It is a fact that Flora can already behave with perfect nonchalant neatness in hotels, tea-shops and classy restaurants … David and I watched Flora pursuing her peas with a unity of enthusiastic tenderness that we could not feel for anything else … As we watched her, she dropped one on her knee. ‘Oh, the pea!’ she exclaimed in her tone of pure amazement, and started to hunt for it with her spoon.

I wanted to be able to write like this. Just a line like it would do me; that perfect movement from speech to writing, that perfect observation of language, done so fast that the actual observation is dispersed, and it appears – a phrase that 18th-century people were very fond of – like life itself. I now realise that I was only able to capture something of the Reverend John Murgatroyd’s feelings, his ‘enthusiastic tenderness’, for his servant’s little bastard daughter in my book Master and Servant because that passage has been in my mind for fifty years. ‘Oh, the pea!’ I have said to myself countless times. Intertextuality is a real and historical thing.

The summer of 2015, a summer of reading and rereading, the first nine of Drabble’s novels; the Robbins Report and its attendant literature, made memory live; I reworked many histories. I started with A Summer Bird-Cage, first published in 1963, Penguined in 1967, and read by me, I think, a year later. I could still recall very precisely that first reading. In 2015 there was the same shock of delight as there had been in 1968: at Sarah’s voice, the confidence, the assurance, the almost arrogance, the length of her utterances, which she enjoys as much as her readers, right to the very edge of irony and self-parody – even the self-deprecation is marvellous, and the sense of self extraordinary. The exultation at being her. I heard it fifty years ago in the same way I hear it now: This Is Us. We – Sussex girls – thought we were marvellous. We thought we were beautiful and intelligent and extraordinary; and funny, and witty, and that we saw the world clearly in all its absurdity. Our brilliant minds did not run along the tracks laid down by Clara in Jerusalem the Golden, not at all; she, her narrator says, ‘never learned to take a simple pleasure in her own abilities; they remained for her a means, and not an end’; we took an exultant pleasure in ours, and if we ever carried a feather duster to a party, we knew full well what we were about. We talked like Emma in The Garrick Year, or Clelia in Jerusalem, with a profound belief in our absolute right to do so. We could have gone on for ever, in love with our complex utterances, in love with our own ideas. During my rereading of Drabble, I remembered that I’d found Warwick undergraduates just a little bit cowed when I first taught them in 1984. But the 1980s were a bad time for most of us, a mean time, an ice age, without much room for self-exultation anywhere under the political regime that shaped our common life. I also thought (in 1969, and in 2015): ‘You are so right!’ when Clelia pronounces to Clara that she can’t love the state and her mother. You have to choose. I’d made up my mind about which I loved by 1965.

There are no young women at university, as undergraduates, in these novels. Clara has finished her degree in French at the University of London and is working for her teacher-training certificate during the timeframe of Jerusalem. The young women from Oxford all have ‘a lovely, shiny, useless new degree’. Louise, in A Summer Bird-Cage, has just spent a year in Paris ‘in a faute-de-mieux middle-class way, to fill in time’ after Oxford. Rosamund Stacey, in The Millstone, is finishing off her PhD in London, and at the end of the book, with her little illegitimate daughter in tow, goes off to a job at ‘one of the most attractive new universities’ – so not Warwick then (architecturally speaking, of course). ‘It was gratifying, too, that my name would in the near future be Dr Rosamund Stacey,’ she thinks, ‘a form of address which would go a long way towards obviating the anomaly of Octavia’s existence.’

In my summer birdcage of reading and rereading I only cried once. It wasn’t the novels that provoked tears, but a government report. I am used to crying over government reports. Various 19th-century commissions of inquiry into child labour in libraries around the country are stained with my tears. I cried over the Robbins Report because I found for the first time something I had always known, in paragraph 810: ‘The young people who will be seeking to enter higher education in the years 1965-66 to 1967-68 were born in the period when the population of this country was beginning to return to normal life after the upheavals and separations inevitable in war.’ That’s definitely me! More babies born in March 1947 than ever before or after!

The trials that their parents had to undergo are in themselves sufficient reason for the country to exert itself to meet the needs of their children. Moreover, if great numbers of these young people are qualified and eager to enter higher education it would be gravely unjust that, simply because so many were born at the same time, a smaller proportion of those qualified should receive higher education than in the age groups coming immediately before or after them.

A government report compiled in the spirit of social justice! I love the state because it has loved me. My tears were tears of acknowledgment. I think of this paragraph as a rather beautiful expression of the social-democratic contract drawn up after 1940. In its emotional and psychological aspects the contract was given clearest expression in John Bowlby’s Childcare and the Growth of Love (1953) and his thesis that love grows by caring, by loving. I love the state because it has loved me.

Or perhaps I cried because of the darker note struck here, or struck by historical hindsight, in the next paragraph of the report:

It is clear to us also that the rejection of large numbers of these young people might well adversely affect the expansion we have recommended. Their younger brothers and sisters might be reluctant, when their turn came, to consider entering higher education and to risk the disappointment of refusal after the years of hard preparation in the sixth form.

Well, the encouragement of example didn’t work for my younger sister, did it? And it didn’t work for the majority who didn’t pass the 11+ exam at the age of ten. Nineteen-year-old Eileen, Rose’s babysitter in The Needle’s Eye, sits slumped in the kitchen, ‘finished, excluded for ever from what she might want to be. She would never try to make the best of things, the gulf between her reality and her aspirations was total, and would remain so.’ I want to remember how many were excluded from the citadel on the hill, Jerusalem the Golden, between 1960 and 1980. Overall participation in higher education by age group increased from 3.4 per cent in 1950 to 8.4 per cent in 1970, 19.3 per cent in 1990 and 33 per cent in 2000, as the 1997 Dearing Report predicted. The 1960s and 1970s saw the establishment of maintenance grants, the movement from college of education to university education departments, and the development of the BEd degree, all of which made higher education seem more possible for many young women. The new universities of the 1960s, offering new kinds of courses in the arts, proved especially attractive to them. In 1960, 3.6 per cent of 18-year-olds from the bottom three social groups entered higher education, compared with an average across all groups of 5 per cent, which doesn’t look like much of a difference, but the occupations in the bottom three socioeconomic classes (unskilled occupations, partly skilled occupations and skilled manual and non-manual occupations) formed a larger part of the population in the 1960s than they did in 1985, say, when 8 per cent of working-class 18-year-olds went on to higher education compared with 35 per cent of those from the top two socioeconomic groups (professional, and managerial and technical occupations). Really, I should be plainer: not many working-class 18-year-olds ever went to university; maybe fewer in the 1990s, proportionally speaking, than in the 1930s. These figures are difficult to compare across the years, and it seems to me that the Office for National Statistics is particularly coy about class; even more coy than it is about gender. An unstatistical summary might go: the number of women pursuing higher education in the 1960s and 1970s was low; the number of working-class men and women even lower. As the narrative voice of ‘Jerusalem’ tells us: ‘Strait is the gate, and narrow the way.’ It was narrowest and straitest at the age of ten.

My friends and I developed the category of middle-class hair sometime between 1965 and 1970 in order to analyse questions of class, education and cultural capital. And yes, some of them were middle-class girls, with middle-class hair and Emma’s achingly fashionable ‘dun and mud-coloured’ complexion and coiffure. But you could easily say to your brilliant friends: ‘I’m middle class, but I don’t have middle-class hair’ – for such a thing was perfectly possible. This was an analytic device invented out of our deeply self-regarding brilliance and wit. An analytic device can transcend class position. I sometimes wonder whether Sarah and Louise in A Summer Bird-Cage are playing out the plot of Middlemarch in their own glamorous and knowing way. In Eliot’s novel, Dorothea and her sister Celia’s hair and dress signal hair and dress as cultural capital. Think of the dead mother’s jewels scene at the very beginning, quite a while before we see Destiny brooding over the West Midlands ‘with our dramatis personae folded in her hand’. As we all know, Middlemarch is Coventry and Loamshire is Warwickshire. Every plot-turn of significance in A Summer Bird-Cage takes place in Warwickshire.

‘However do most of us keep upright?’ Kate Armstrong, the disillusioned feminist, asks in The Middle Ground (1980). ‘Like tightrope walkers, by not looking to either side, I suppose, like horses in blinkers. I should never have looked. I should never have looked, I should never have looked.’ They won’t get you; but only as long as you don’t look down. ‘She would survive because she had willed herself to survive,’ Clara thinks, ‘because she did not have it in her to die. Even the mercy and kindness of destiny she would survive; they would not get her that way, they would not get her at all.’ The great story of these novels is that you can refuse your fate, refuse to be got. As long as you stay on your feet. So not much like Middlemarch then.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.