Why should writers mind about clothes? More than any other profession they spend their most productive hours alone. They can wear anything – or nothing – and nobody is any the wiser. Yet as Virginia Woolf wrote in Orlando, clothes have ‘more important offices than merely to keep us warm. They change our view of the world and the world’s view of us.’ In the novel clothes propel the narrative of Orlando’s passage through time and gender. In Mrs Dalloway the green dress is in effect a character, an expression of what Woolf described in her diary as ‘the frock consciousness’ of life. She took considerable care about her own appearance but like most of the writers Terry Newman discusses in Legendary Authors and the Clothes They Wore (HarperCollins, £20), she was not interested in fashion per se. Her friend Madge Garland, who edited Vogue and later gave her advice on clothes, was astonished when she met Woolf for the first time and ‘she appeared to be wearing an upturned wastepaper basket on her head. There sat this beautiful and distinguished woman wearing what could only be described as a wastepaper basket.’ When she was photographed for Vogue Woolf wore a dress that had belonged to her mother. It was out of date and ill-fitting and worn with unmistakable if enigmatic intent.

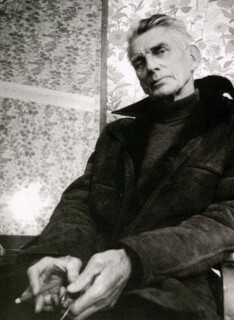

Newman’s immensely enjoyable book ranges from the 19th century to the present and rearranges the literary canon with abandon to illuminating and sometimes comic effect. Organised like an extended magazine feature it has sections on ‘Signature Looks’, which include ‘Glasses’, ‘Hats’ and ‘Suits’, the latter bringing Gay Talese and T.S. Eliot into unlikely proximity. There are also pull quotes with such fun facts as that Jacqueline Susann’s ambition as a schoolgirl ‘was to own a mink coat’, and in the early 1970s Samuel Beckett used a ‘now classic leather Gucci hobo holdall as his day-to-day man bag’. Beckett, Newman suggests, would have been an ideal model for Comme des Garçons and with that thought in mind a photograph of him gazing out in moody monochrome looks for a moment like a page from a Toast catalogue.

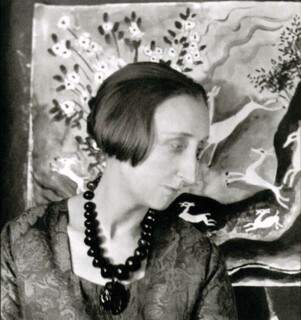

The juxtapositions are playful but not trivial. The relationship between the work and the clothes is discussed but not laboured. Unsurprisingly, perhaps, the women and the gay men make the most interesting studies. Simone de Beauvoir, whose silk dresses, turbans and perfect manicures bore witness to her willingness to undertake what she called ‘the work’ of fashion, says in The Second Sex: ‘dressing up is … a uniform and an adornment; by means of it the woman who is deprived of doing anything feels that she expresses what she is.’ Sartre, wearing a suit on the beach at Copacabana, looks dreary beside her. John Updike in his dull dad jumper feels like a token inclusion, Hunter S. Thompson naturally stands out. His Hawaiian shirts and safari suits became so recognisable that Gary Trudeau turned him into the demonic Uncle Duke of Doonsbury, much to Thompson’s chagrin. As he said, ‘nobody wants to grow up to be a cartoon character.’ On the whole, though, it is those writers who saw the potential of clothes to create an identity and visibility that society would conventionally deny them that are the most revealing. This was the impulse that propelled Quentin Crisp, ‘blind with mascara and dumb with lipstick’, through the ‘dim streets of Pimlico’. ‘Sometimes I wore a fringe so deep that it completely obscured the way ahead,’ he recalls. ‘This hardly mattered. There were always others to look where I was going.’ Edith Sitwell’s huge jewellery and flowing robes, which gave her the appearance of ‘a high altar on the move’, were also the result of a desire to turn the tables on the world. Made to feel self-conscious about her appearance as a child, as an adult she ensured that everyone else should be conscious of it too.

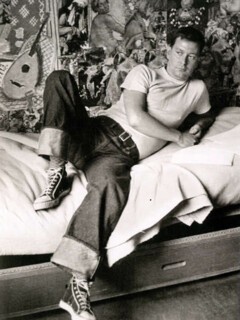

Clothes come between the naked self and the world, as does writing. Where the dividing line is drawn varies. For Crisp and Sitwell their appearance was part of their work and of themselves: they were performers as much as writers; while Oscar Wilde’s clothes were an ironic complement to his writing. A leading member, with his wife, Constance, of the Rational Dress Society, which campaigned to remove the constraints of conventional clothes, especially the corsets and bustles that afflicted women, Wilde had a conception of rational dress that saw him arrive in New York for a lecture tour wearing ‘a low-necked white shirt, with a turn-down collar of extraordinary size, and a large light-blue silk neck scarf’ set off with a fur-lined ulster, turban and pale pantaloons. His dress was a form of hiding in plain sight and it worked – it wasn’t the clothes that undid him. He was disparaging of fashion – ‘a form of ugliness so absolutely unbearable that we have to alter it every six months’ – and Newman makes the point that fashion has followed writers more often than the other way round. Beauvoir inspired the Beatniks and Joe Orton’s ‘rough casualness’, the heavy jeans with deep cuffs and tight white T-shirts, influenced Vivienne Westwood and Malcolm McLaren to call their King’s Road shop Sex after an entry in Orton’s diary: ‘sex is the only way to infuriate them.’ They stocked a suitably lurid Prick Up Your Ears T-shirt.

The most intricate and poignant of Newman’s examples is Sylvia Plath. The Bell Jar is permeated with frock consciousness. The protagonist, Esther Greenwood, who has come to New York to a dream job on Mademoiselle magazine, ends by throwing her clothes away: ‘A strapless elasticised slip which, in the course of wear had lost its elasticity, slumped into my hand. I waved it, like a flag of truce … piece by piece, I fed my wardrobe to the night wind … like a loved one’s ashes.’ Yet Plath continued to wear the shirt-waister dresses, hats and gloves that reminded Ruth Fainlight when she met her of ‘one of my New York aunts dressed for a cocktail party’. The suggestion that she was dressing for a part she couldn’t play is perhaps a little glib. There was something in those clothes that was her; she was also the loved one cast away like ashes in the wind. Newman doesn’t discuss Ted Hughes but the contrast between Plath’s knife-edge relationship with clothes and Hughes’s appearance of being made out of his subject matter, heavy corduroy, moleskin and leather, is surely telling. He was so famously enthusiastic about his trousers, occasionally measuring his guests up for a similar pair, that he was rumoured to be on commission from the makers.

Newman makes no claims to be exhaustive and ‘legendary’ is not the word everyone would use to describe all these writers, but she sets the mind going along interesting lines about others who might be given the same treatment: Barbara Pym, beneath whose twinset beat a passionate heart; Anita Brookner with her neatly tailored outfits and the fine-spun auburn up-do exuding poise and sadness; and all the others who in various ways inhabit their work.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.