An enormous queue of well-dressed men and women formed at Tate Britain on the opening night of the Hockney exhibition in early February. It inched forward, a few more guests at a time; at the back people craned their heads trying to work out the reason for the bottleneck – or gave up and went to get a drink in one of the galleries off the octagonal hall at the centre of the building. The explanation was Hockney himself; he was in one of the first rooms, and the thrill of being in the same place as the artist evidently made it hard for people to move on. It would have been odd had Hockney not been the centre of attention. But it is a curious phenomenon even so: hundreds of people transfixed by the presence of an artist whose appearance is as distinct and as recognisable as his work.

Portrait of the Artist, an exhibition at the Queen’s Gallery (until 17 April), includes two images of Hockney. All the paintings, the prints and the sculpture are from the royal collection, which possesses an extensive range of artists and their portraits from the late 15th to the 19th century, though fewer 20th and 21st-century examples. There aren’t many collections that could mount such an extensive exhibition on a subject with such narrow parameters without borrowing from elsewhere, but the English monarchy has long liked to acquire pictures of artists. Charles I, a king much absorbed by how he was himself depicted, bought, commissioned or was given numerous artist portraits. The Commonwealth sold Charles’s collection, and although many of those pictures were reacquired by Charles II, a Dürer self-portrait, for example, given to the king in 1636, stayed in Madrid – it’s now in the Prado. As if to acknowledge the importance of that portrait and its association with the royal collection, the first exhibit at the Queen’s Gallery is Dürer’s The Bath House, a woodcut he made at much the same time as the portrait. He’s one of seven near-naked bathers and he leans on a wooden standpipe, his head resting on his raised right arm as he looks on at another bather playing a pipe. A tap obscures his loin cloth-covered penis, as if remarking on the artist’s virility.

The artist as gentleman, the artist as courtier, the artist as thinker, the artist as a young man or woman, the artist as artist and handsome figure: these are some of the varieties of representation of the artist from the Reformation and Renaissance to, say, David Hockney. Van Dyck made numerous self-portraits. His friend Rubens’s picture of him confirms the likeness Van Dyck made in his own work. Rubens’s self-portrait is both a picture of a successful man, and an advertisement for himself. He has his head turned to the right, is wearing a black, broad-brimmed hat and has the facial hair of his patron. It has become the most famous image of the painter: Charles I considered it important enough to give it a position where he could see it every day when he was in London.

The curators of the exhibition make a point of accuracy and technique: a self-portrait requires complex mirror arrangements for the artist to be able to see themselves as they are – not just their reflection. Bernini had piecing dark eyes. A French official at the court of Louis XIV tells us so. ‘His temperament is all fire. His face resembles an eagle’s, particularly the eyes. He has thick eyebrows and a lofty forehead, slightly sunk in the middle and raised over the eyes. He is rather bald, but what hair he has is white and frizzy.’ That was written in 1665; in the black and white chalk drawing he made a decade later he still resembles exactly that description.

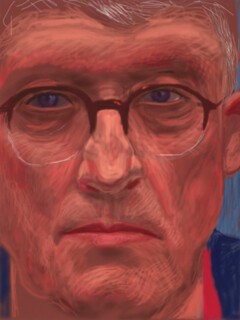

The first picture of Hockney, in order of appearance, is a self-portrait from 2012. His head is tightly cropped, and he has left out his right ear and included only half of the other. Some of his chin has been sliced away, and there’s only a hint of a hairline. The face is unfurrowed, the skin is uncannily youthful, yet the eyes have an unfocused blankness about them. It’s technologically interesting; it was drawn using an iPad, and every stroke Hockney made was recorded sequentially. The second Hockney image is a black and white photograph taken by Dimitri Kasterine in Paris in 1975: Hockney is sitting crossed-legged with his arms folded; he’s wearing a velvet suit and a dandy’s fin-de-siècle tie. In both images, he looks out to the viewer through round spectacles, his lips serious and pursed. In the more recent self-portrait he’s an ageing man hinting at his own sensory diminishment. But it’s unmistakably Hockney by Hockney.

Almost all the artists in the Queen’s Gallery show were successful, but the curators don’t entirely explain what that success meant. Last year, the National Gallery presented an exhibition of the art that artists have bought for themselves, but neither exhibition has addressed the artist as economic agent, their money or their debts. When Mark Carney announced that Turner would be on the next £20 note, he didn’t mention that Turner was a stock holder in the the Bank of England. Thomas Rowlandson was once a rake; in The Chamber of Genius he depicts a dishevelled artist at work at his easel in a chaotic room that is home to a wife, two children and their dog. Rowlandson died a rich man – it took Sotheby’s three days to sell all his drawings, prints and paintings.

Edwin Landseer’s picture of Francis Chantrey is a non-representational portrait of its subject; it’s of the interior of Chantrey’s studio. Mustard, the dog given to him by Walter Scott, lies on a table covered with a red cloth, and leans against Chantrey’s bust of Scott. Two dead woodcock lie nearby, upside down in the foreground, as if they had just fallen from the sky – Chantrey once killed two of those birds with a single shot. Chantrey too was materially successful. The £100,000 bequest given to the Royal Academy after the death of his wife in 1875 was for the purchase of work by British artists. It funded the Tate Gallery’s acquisitions for decades.

‘Do you not agree that the fate of the portrait is rather pathetic,’ Jacques-Emile Blanche, an artist famous in his day for his portraits, wrote in a letter to William Rothenstein, who was another – ‘unless the name of the artist be such a famous one that no change in public opinion could possibly prevent them from falling into oblivion.’ None of the artists on show at Buckingham Palace has been wrested from oblivion; they all have recognition. Royalty doesn’t tend to accommodate failure or moodiness: as the curators explain in their catalogue, this collection of portraits tends to favour conformity rather than rebellion.

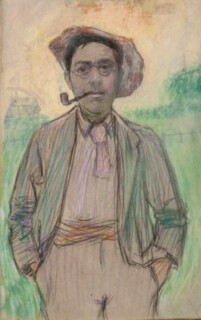

Hockney was born in Bradford; so was Rothenstein – artist, writer, teacher and one-time principal of the Royal Academy of Arts. There is no Rothenstein in the royal collection, but then none of the artists of Chelsea, Bloomsbury and Camden Town is included either. The last illustration in Rothenstein’s memoirs is a reproduction of a self-portrait: And Yet Again was its title. Rothenstein painted himself many times – typically looking out from the canvas, with his head turned over a shoulder and his face consistently bemused. ‘His work shows a fierce – an almost exasperatingly high – faith in reality,’ Roger Fry said of Rothenstein pictures. In one of his first self-portraits, painted when he was a student in Paris in the 1890s, he is smoking a pipe and wearing a straw hat and a crumpled white suit. In his dandyish get-up, he doesn’t look unlike young Hockney in Paris eighty years later.

On his last journey to Paris in 1939, Rothenstein visited Blanche. As the two men talked in Blanche’s studio about the forthcoming catastrophe, Blanche drew Rothenstein’s portrait: ‘You are pleased to have done a brilliant piece of painting,’ Rothenstein said at the end, ‘and I am relieved to look fairly intelligent and not too repugnant a person in your portrait.’ When he returned to Britain, Rothenstein had lunch with Walter Sickert – he’d first met him at Whistler’s house in Paris in the 1890s. Sickert had turned eighty and was living in a large house near Bath. He had a portrait of himself in his painting room which had been made by Thérèse Lessore, his third wife. In the painting, Sickert was dressed in an academic robe. He told Rothenstein how delighted he was with it – the artist as a doctor of letters.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.