On 27 December 1950, 66 years ago, at the age of 66, the German émigré painter Max Beckmann suffered a heart attack and died on the corner of Central Park West and 69th Street, where for the past eight months he had rented a small apartment and a studio. He had been on his way across the park to the Metropolitan Museum of Art, to view the latest (and last) of his self-portraits, the rather gaudy and saddening Self-Portrait in Blue Jacket (and Orange Shirt and Purple Sweater-Vest), where the almost unrecognisably pinched-looking painter has lost a couple of hat sizes (as if a lifelong thumb were now an index finger). Even what the note beside the painting charmingly refers to as the ‘ubiquitous cigarette’ (recte, the inevitable cigarette: it may always be there, but it knows its place) looks shrunken to a bidi.

I take Beckmann to be one of the great painters of the 20th century, his life one of the great 20th-century artists’ lives, and his diaries, the Tagebücher 1940-50 (he destroyed earlier years, lest they fell into the hands of the Nazis), one of the great autobiographical records. His work, life, career and personality fully manage to span the unimaginable cultural shifts from the stiff collars of Wilhelmine Germany to our epoch of the artist as awkward little public client and university appendage. As someone noted, a little gnomically (but it’s the truth), ‘Beckmann was time.’

He was successful early, painting John Martin-like catastrophes on a huge scale: visionary, awful, sandy things. The first monograph on him appeared before the First World War, when he was still in his twenties. In the war, he was an ambulance man on the Western Front, before suffering a complete mental collapse in 1915. The 1920s were his decade. He was far and away the best-known painter in Germany, moving effortlessly in rarefied, moneyed circles in Berlin and Frankfurt (more books came out about him): a sought-after portraitist, painting in the half-satirical, half-faux-naif Neue Sachlichkeit manner (the people look like dolls, dolls with real skin), with a new wife, Mathilde Kaulbach (the ‘Quappi’ of many of his portraits), a pied à terre in Paris and a casual and privileged engagement at the Städel Museum in Frankfurt (where sometimes he had one student). His paintings of the time were both rickety and rackety.

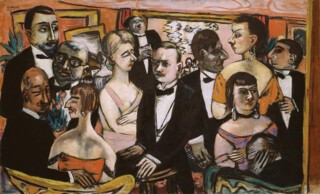

He had nothing to do with any artistic grouping or individual. (In this he resembles Otto Dix – maybe it’s all German solitudinarianism, out of Nietzsche or Caspar David Friedrich.) His boldly outlined conical or tubular forms, unconventional colour balances and bright, acidic palettes stand out anywhere. He painted social milieus of pleasure, soirées and resorts, bars and dances, the ambassador looking despondent in Paris, the vast German actor Heinrich George en famille, with dog. In self-portraits, he stylised himself as an industrialist or banker, in formal Western rig of dinner jacket and cigar, aloof and unmistakable. Still, Alfred Döblin, seeing a photograph of an unidentified Beckmann, judged him to be a sadistic public prosecutor, and one can see why: the rugby hooker’s build, the robust skull, the cold burn of the eyes, the wide, extravagantly downturned mouth (so perplexingly reminiscent of the late ‘my mother-in-law’ British comedian Les Dawson). Somehow, I am always drawn to these short, pyknic or mesomorphic creators, whether they are Brodsky, Benn, Beckmann or my father.

As the Nazis came up things grew abruptly tight for Beckmann. He lost his job in Frankfurt (‘public funds for Jew lackeys like Beckmann’), was pilloried in the press and increasingly prevented from showing. The day before – or the day after, accounts differ – the extraordinary Munich exhibition of entartete Kunst, menacing and pillorying Expressionist and Surrealist and abstract art, he and Quappi moved to Amsterdam, and Beckmann set up there, in an old tobacco warehouse. Those years were a model of artistic independence, endurance and persistence under extreme adversity and (putting it mildly) distraction. A banned painter in an occupied country: as good as a writer under censorship.

They stayed in Amsterdam through the war, from 1937 to 1947, he implacably, phlegmatically, heroically working, drinking, reading, pessimistically musing. The nightlife was painting, sleepless dread, or thoughtfully listening to waves of Allied bombers passing overhead. Dutch words made their way into the diaries, and stayed there: terms for ‘explosion’, ‘easel’, ‘bicycle’, ‘small gin’, things he encountered in daily life. To go out was always op straat. Twice he was examined for the military, twice failed the physical. After the war, he got invitations from Germany, but turned them down (‘Lots of mail, invitation from Berlin, ha-ha’) – he never set foot there again after 1937. A month in the south of France in the spring of 1947 is one of the great rhapsodic encounters with a place ever recorded (think of Bishop in Brazil, or Mandelstam in Georgia). ‘First time I left abroad for abroad.’ That year, the painter Philip Guston won a Guggenheim and took off for Europe; nature abhorring a vacuum, Beckmann agreed to fill in for him at Washington University in St Louis. Two years later, in 1949, he was offered a job in Brooklyn, and took it. Ergo the Met’s Beckmann in New York (until 20 February). He had just 16 months there.

America – ‘so large,/So friendly, and so rich’ (Auden) – likes to see itself as both ‘coming through’ and fervently desired, though neither is necessarily the case with Beckmann. The conventional image is the cavalry, but I wonder if the gold-sprayed angel-led equestrian statue of Sherman outside the Plaza Hotel isn’t more appropriate to Beckmann. He was of course both twice as old as Auden when he finally arrived (sixty to Auden’s thirty) and – steeped in German Kulturpessimismus – infinitely pricklier. A wild animal in a petting zoo. Gratitude was certainly a part of the picture, and wonder, but so too were irritation, anxiety, apathy and disapproval. In 1939, when he thought he really needed one, he was refused a visa. By 1947, he wondered about the wisdom of going at all. ‘Apart from death, this – departure, ugly or beautiful – will surely be the last great experience vouchsafed me by life, so better enjoy it.’ There was no chance of this ‘irascible’ getting together with the 15 Abstract Expressionist coves dubbed ‘the Irascibles’ in Life magazine in 1951.

Freshly arrived in St Louis, he put it cautiously: ‘It is possible that it may be possible to live here after all.’ He habitually expresses more enthusiasm for the art and cultures of Mexico than for anything American. Without the support of his two gallerists, J.B. Neumann and Kurt Valentin (both German-Jewish émigrés), and his two American collectors, Morton May and Joseph Pulitzer (both in St Louis), Beckmann would have cut very little ice in the States in the unfigurative, prudish, ahistorical and self-obsessed 1940s and 1950s. He sold hardly anything, received daft reviews, was unwilling to issue the explanations and justifications craved by Americans, and to keep body and soul together, taught students to whom he was at best a ‘glorious anachronism’. As for place, he was too old, too set in his ways, and too self-propelled to need it – and too briefly there to make much of it.

He already came with what I think John Cheever calls an ‘incantation’: he worked on several paintings at once, often at night, by artificial light, in his windowless studio. His gift was portable, and kept giving. He measured out his life in paintings. A Beckmann is a Beckmann. Place is little more than the difference between the ‘F’, ‘P’, ‘St Louis’ or ‘NY’ that he set next to the year at the bottom of his paintings. (The one city picture he made in New York at this time happens to have been a jaunty view of San Francisco, which he visited for a couple of weeks.) On the brink of his 65th birthday, he tried out the following unsentimental obituary for himself: ‘Finally, Beckmann removed to a large, distant land, and gradually we see his form grow indistinct, until finally it disappeared altogether in the measureless expanse.’

Nor did things necessarily or quickly look up for him once he was dead and filling an urn under one of his triptychs, The Argonauts (1949-50) in Quappi’s new flat on Broadway. The centenary show in 1984 put in stops in Los Angeles and St Louis, but not in New York. More grievously, the Met in 1971 ‘de-accessioned’ three of the Beckmanns they had bought. A stung Quappi duly deeded The Argonauts to the National Gallery in Washington DC. This exhibition, then, is not least a Wiedergutmachung: an act of graceful atonement and redress on the part of New York. Up to a point: The Argonauts are in the catalogue, but not in the show.

Sabine Rewald – German, or ex-German from the sound of her – has admirably curated and described the thirty-odd paintings (almost all there were) that Beckmann completed in the New York time, or that were acquired by New York collectors. It’s a good way of getting a sort of overview of the work from 1920 to 1950: seven self-portraits, a couple of portraits, three gorgeous paintings of Quappi (Vaudeville Act, Quappi with White Fur and Quappi in Grey), some of Beckmann’s typical (and very unusual) scenic or group pictures, a triptych, a few landscapes and still-lifes. Even in the minority of pictures where there are no human figures, there is grandeur and theatricality: in chuffy smoke, in clouds, in lettering and toys and games. Even the junk in the props room seems mythological.

One of the interesting things about Beckmann is how much the paintings moved and morphed under him. The form of the triptych was arrived at adventitiously; he simply had more material than could be fitted onto one canvas. Colours shifted all the time. In the course of five months, the portrait of Quappi went from ‘green and blue’ to ‘green, black and yellow’ to ‘blue, green and yellow’ to the final ‘grey’. The seated figure, outlined in black, upright, smoking, arms and legs crossed, is wearing an elegant pale grey hat and coat, against a green, round-shouldered chair and a grey and brown panelled wall. Earth colours, nature colours. The curve of necklace, ear and chin, the gleaming hair breaking on the shoulders, the bend of the arms and the endless drape of the long-fingered hands with crimson nail-varnish: it’s as lovely as anything by Matisse or Modigliani. Objects – Beckmann had a positively theatrical way with ‘speaking’ props and costumes – and expressions were there one day, gone the next: a smile, a raised forefinger. A circus trapeze gives way to a flugelhorn; a ‘Leda and the Swan’ is made over into the exquisitely provocative Woman with Mandolin in Yellow and Red.

In some way, these paintings are not copied from any reality, not Platonic approaches, or aspirations towards any ‘ideal’ scene, so much as improvised solutions to self-set problems of structure and colour. Plaza (Hotel Lobby) of 1950, one of very few New York subjects painted by Beckmann in his time there (and no exteriors), may look like a stained-glass rendering of a jam-packed subway scene, but basically it dramatises the rhythmic return of an orangey red – in a fez, a woman’s hat, a man’s face, a woman’s hair – while the tonic green appears in two versions, jade and a yellowish pea-green, strong and weak, at the top and bottom of the picture.

Some of the paintings are riots, you don’t know where to look – the triptych called The Beginning, the nightmarish fascist scene called Bird’s Hell – but most operate powerfully with reduced palettes: Portrait of Irma Simon with fawn and sky-blue; the 1938 Self-Portrait plays off maroon and eau de Nil; Paris Society runs on the black of the men in evening dress and the reds and pinks and corals of the women’s toilettes and the room; the Oyster Eaters similarly enjoys a palette of black, pink and mauve, set off by the grey-green of the oysters themselves; the voluptuous Alfi with Mask is chocolate and chartreuse, Dancer with Tambourine cobalt, ochre and black. The colours – so settled, so decided – play across a picture like the notes in a tune or the assonantal syllables in a line of verse.

Structurally, or formally, it is striking that so many of the pictures are in longish formats, in many cases further narrowed by vertical framing devices, drapes or ladders or unspecified blinkering blocks of colour or a zigzagging pattern. We see things in Beckmann’s pictures as though through closing elevator doors or theatre curtains. An image is barely retrieved: imperilled, exalted, made precious by its height. And then, as Rilke says in ‘The Panther’, it is fetched into the heart and abruptly ceases to exist.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.