We still live among wild animals, just about: the birds that flit and scurry and sing and build in our gardens. They are like iridescent spray: the rose-flush on the breast of a male chaffinch, the gold ring round the eye of a blackbird, the jet-black cap above the slatey body of a great tit. Sparrows are said to have become much less common, but 31 of them have frequented my garden in the past seven days, to say nothing of blackbirds, collared doves, coal tits, starlings, chaffinches, a song thrush, a dunnock, a woodpigeon and a great tit, and that during a typical spring week in a village of 630 households on a detrunked A-road, half a mile from a motorway and a little more from the Glasgow-Euston railway line. A few weeks ago in a nearby wood I saw two buzzards flapping at each other on the ground in a fierce kerfuffle. I’ve heard the click of beaks as two swifts met – kissed? – in midair overhead. A few years ago my wife called out in alarm: a swift had crashed to the ground just outside the back door, struck down by a sparrowhawk: it gave one gasp and died, and I buried it at the end of the garden. Encounters with birds have enriched my life, whether it was the golden eagle spiralling silently upwards a few yards below me in a corrie of Beinn Alligin in Torridon, or a woodcock zigzagging through a deserted orchard two hundred yards east of my Cumbrian home, or a kestrel darting in and out of a Yorkshire cliff as it hunted the nestlings of the martins’ autumn broods and feathers spattered down around my feet.

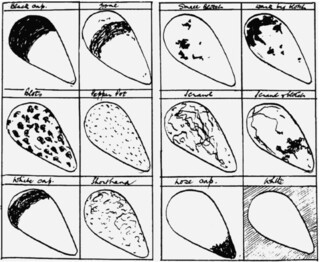

To come upon a bird’s egg is to be close to a natural wonder, even if Birkhead is perhaps a shade too purple in saying that eggs ‘have an erotic aura all of their own’. My own sightings of eggs have been infrequent (collecting the eggs of Khaki Campbell ducks from among the reeds near a house in Aberdeenshire during the war, for example, or stealing an egg from a moorhen’s nest beside a pond in Aberdeen, which was the last time I ever took an egg home to blow and keep, because it became clear to me that such an act is a violation). The birders discussed by Birkhead, from the 17th century until what he calls their heyday in the 1930s, had no such scruples, from the Native American Beothuk in Newfoundland, who harvested guillemots and great auks for their flesh and eggs, to British collectors such as George Lupton, a wealthy lawyer who, in the 1930s, paid the professional climmers – cliff-climbers – of Bempton, just north of Flamborough in Yorkshire, to collect guillemots’ eggs for his collection. That amounted to more than a thousand eggs and is now housed in the Natural History Museum’s outpost at Tring. Probably about 48,000 eggs were taken annually from the Bempton cliffs; the harvesting had been going on since the 16th century, and ended only when taking wild birds’ eggs was made a criminal offence in 1954. Guillemots’ eggs are said to be tasty scrambled. Lupton used to blow the day’s haul in the kitchen of his Bridlington landlady; when he had finished she took ‘the bowl of yolks and albumen that Lupton left – by arrangement – and scrambled them for her son’s supper’.

Such picturesque details are not the main business of this book, which is really a scientific monograph. Colleagues and predecessors are fully acknowledged in the course of an exact description of what a bird’s egg is. History is attended to in the citations of eminent ornithologists, from Aristotle onwards, that open most of the chapters. Birkhead covers the shape of eggs, their colouring, the function of albumen in keeping microbes at bay, fertilisation, laying, incubation and hatching. He tells us, for example, that the dimpled space at the blunt end of a hen’s egg is an air cell that provides the amount of air needed by the chick just before it hatches. With nearly all birds, whether their eggs are small or big, about 15 per cent of the egg’s initial weight is lost as water vapour between laying and hatching: ‘In other words, the composition of the newly laid egg has evolved through natural selection to ensure that the newly hatched chick has the right composition.’

Such facts don’t prove, and are not adduced by Birkhead to support, a rose-coloured view of nature. One gibbon in eight in the wild has fractured a bone, though we think of gibbons as supremely agile, and the equivalent in Birkhead’s account is that ‘about 10 per cent of all eggs laid by wild birds fail to hatch.’ He is frank about such failures, and what we don’t know or fully understand about them. He has spent much of his life studying guillemots, on the island of Skomer off the Pembrokeshire coast, but still doesn’t know how they warm their eggs effectively under harsh conditions: they have a brood patch, an area bare of feathers that allows the egg direct contact with the adult’s warmth, ‘but only a portion of the egg is in contact with that; the other side of the egg lies directly on the ice or the rock ledge – not even on the bird’s feet as in some other species.’

Such a passage is typical of The Most Perfect Thing both in its candour and in its closeness to fact. As is so often the case, this doesn’t deflate some sacred mystery, but enriches our sense of and our appetite for the infinitely unfolding world of nature in which we find ourselves. Although Birkhead is a scientist, this doesn’t mean he is restricted to objective measurement. In one passage he wonders why ‘paintings of eggs are extremely scarce.’ This puzzled me recently as I worked through Caroline Bugler’s monumental The Bird in Art (2012). In its 250 images eggs are to be seen only three times, and the most telling of these are in Hieronymus Bosch’s extraordinary Garden of Earthly Delights. Bosch’s eggs are monstrous and symbolic. In the large central panel a white egg lying on the shore of a lake disgorges into the water a posse of little brown men. In the ‘Hell’ of the right-hand panel a bird-man with blue limbs, a bristling beak and glossy eye swallows a pallid human whole while excreting a transparent blue egg in which a human is enclosed from the waist up. These eggs are nightmarish and menacing, not domestic or comfortable or fertile, and Birkhead’s suggestion that the reason for the scarcity of their representation is that ‘rendering them in two dimensions simply doesn’t do it for most people’ is hardly an explanation. Do lifelike and healthy eggs figure so rarely in paintings because we so rarely see them? When we see a box of eggs they are no longer themselves. The shattering of a wild bird’s egg feels like an especially acute violation of nature, partly because the egg is a symbol of life as it perpetuates itself, partly because the smooth, hard, brittle oval is the epitome of what should be left intact. Birkhead, at his most descriptive, evokes the chaos he found in 1992 on one of the Gannet Clusters, an archipelago off Labrador:

Everywhere I look I can see eggs: blue, green, red and white, but mostly an indifferent khaki colour. Almost all the eggs are intact but some are broken with their orange-yellow yolk and bloody part-grown embryos spilled out onto the rocks. There are eggs piled up in corners, eggs in shit-filled puddles and eggs wedged in crevices. Hundreds, possibly thousands of guillemot eggs have rolled away from where they were laid and now lie cold and abandoned.

Arctic foxes had ravaged the birds, after the ice retreating in summer had left them bereft of their habitat. A feast for the animals, ruin for the birds. Birkhead does not turn the predators into villains; he knows that animals must eat one another, and notices the one ‘redeeming’ feature among the chaos: ‘I found two or three isolated guillemots that had returned, found their egg and resumed incubation … With no neighbours to help protect them from predatory gulls and ravens, their chances of rearing a chick successfully were slim indeed.’

This natural chaos is dwarfed by human plundering. In Crow Country (2007) Mark Cocker records that in the 19th century a marshman in the Norfolk Broads would deliver 1920 lapwing eggs a season to game-dealers in Yarmouth to sell on to clients in London: ‘That one man in that one spring period, with his buckets of chocolate-patterned coffee-coloured eggs, was carrying away more lapwings than nested in the entire Norfolk Broads at the end of the 20th century.’ That was to gratify the taste of egg fanciers. At least the islanders of St Kilda, who could harvest sixteen thousand seabirds’ eggs in three weeks, were gathering food to keep themselves alive in that cramped and rocky environment.

Birkhead does not on the whole do science out of a sense of mission, although he is quietly sure that scrupulous research has the power to benefit us all. Developing a salmonella vaccine for commercial hen flocks reduced the number of salmonella cases in the UK from 14,700 a year to 600; in the US there are 100,000 cases every year because the cost of vaccination is thought to be too high. But the UK too is now at the mercy of government meanness and stupidity. Birkhead’s long-term guillemot study on Skomer was threatened with closure because of Welsh government cuts but has been saved by donations brought in by crowdfunding. Long-term studies are valuable, Birkhead argues, because ‘they will allow us to investigate environmental problems that we haven’t yet even imagined,’ just as ‘museum eggs collected for one purpose in the 1800s and 1900s were later used to look at the effects of acid rain.’ The Most Perfect Thing is sober and expository, and more concerned to set out the detail of membrane thickness in birds’ eggs, for example, or where pigments are located in the eggshell, than to describe, say, a bird cliff, its crowds of creatures, its chorus of yells and cackles, its looming drop, as a traveller or a novelist might do. It is much more On the Origin of Species than it is The Voyage of the ‘Beagle’. Its value is in the exactitude of its science and its implicit belief in the value of sustained and focused looking.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.