Lesson Three

Dad was not dad. Dad was the mad train

screaming daily into the station of his home,

white-hot brakes shrieking, exploding across

the platforms of the rooms. So regular,

so on time, you could set your watch. Five hours.

Four. Three. Two. The skies were my watch.

I saw the evening redden, and I hid.

Hiding to nowhere. A phrase I still hate.

Dad’s train shivered and splintered the front door.

He would steam home and hit me for being

home. If he didn’t hammer me, he’d waltz

on toys with his work boots and kick the wreckage

in my face. Then he’d stamp on my fingers.

I’d dive under the bed to save my hands.

Lego. He’d grind Lego to smithereens.

A hiding. That’s the toy he brought home.

When I was six, I hid inside a bottle

of corked cooking brandy. Passed out cold. Ten:

his train tore through the walls, screeched

to a halt at the buffers of the prone boy.

You’re fucking pissed, he hissed, smiling. He chugged on

on on, leaving soot and sweat all over my skin.

But I’d dodged a beating. Slight strategy.

I’d even cheered him. That was Lesson One.

Lesson Two was not to speak. Not to exhale

one white word. Silence starved the furnace.

Dad’s coal-heart cindered. The steel face flickered,

lit lightly, pistons heaving on heavy wheels.

Huff Huff as his engine snored on its sleepers.

There were no more trains that night.

Hiding. Not speaking. Habits grafting

to a character that’s there, that’s not there –

that shared dad’s table, hearth, his suddy bath

each Sunday night; and knew never, never,

never to speak or show or point or tell

or mind or feel or think, or stare. Or steal.

I stole silence. I stole hushed thunder.

Trains could come and go. Ghost-trains at night.

Rippety-trip-rippety-trip. I fell.

I fell over my tongue. Or my tongue tripped

over me. At school I had spoken, read

aloud, sang in assembly. Teacher’s pet

my brother spat (he, a half-slid train

off the rails). Silence then: then a stammer.

Nothing between or beyond. No straight sound.

All strained. Nictitating. Reined.

Dad’s train steamed, fumed, fretted on its platform.

I could hear him grinding along the rails

of loft-rafters at night. He would half-slide

my bedroom door open, in the sidings

of dark. But the boiler blew up in him.

Dad’s lungs were smoked-out. They hung with tumours

soot-thick. He coughed like a strangling:

throttled, mouthing, mantling over a bucket,

over boltings of spew. I’d take that light-blue bucket,

flush the stuff, sluice it, kneel once more beneath

his retching, ravaged, wrought-apart chest, almost like I

was waiting. Waiting for him to get some steam up.

To explode. Through the walls. So I said nothing.

The sick, the dying. They can say anything.

The Juvenile Court, Fleetwood, 1979.

My So sorry speech so slowly rehearsed

for hours to a mirror, my brother banging

and banging on the bathroom door. Will you

fucking well stop yakking to yourself!

Standing in the dock, fish-stench from the Docks

offal-pungent until the trawlers dry-docked

in the Cod War. I fell over my tongue. Or

my tongue fell over me. I had to tilt at it.

To sound like 13-year-old truth.

I realise I have done wrong. I am sorry

for my actions. I promise never to do this again.

How far did I get? I re- I re- I re- !

(then higher, panicking) I RE- ! My brother

was snorting, pissing himself. The young judge

gazed over his glasses, mystified, encouraging.

His slight kindness turned the tap – words. Words, like w-

w-w-w-w-w-W-W-W WATER

shot out as if hosed, splattering meaning

in the dropping well of conscience.

‘What did you say?’ – the judge leans forward, ‘I re-?’

I am not sorry to tell you I’m not sorry.

Am I lying? I’m not lying. This was Lesson Three.

Husbandry

When I was a baby, my mum planted a row

of four baby apple trees at the foot of our garden.

She winter-washed the saplings scrupulously.

In March mum slapped and bound grease tight around

to daunt caterpillars inching to the leaves.

Infant trees arose and poured pink blossom

each apple flower cross-pollinating.

Charles Ross. Laxton Superb and Fortune. Beauty of Bath.

I grew with these trees at the same height each year.

When I reached seven, mum took pruning shears

to them and sealed the dripping sap with tar.

This wounding only spurred a spurt of growth.

Next year the trees began pumping out apples.

I was drawn by their blossom’s scent each April

the moment that they budded on the boughs.

They seemed to burst from bud to fruit overnight.

The lure for a child was to pluck and bite

those tart infant apples before they swelled;

there were casualties by gall and codling moth

or fruit pecked putrid by blackbird or thrush.

To hide my thefts, I took only babies,

marble-like, equally, from each of the trees.

I prayed for gales. Windfalls were treasure.

In September we took them in their season.

Salted to drive out bugs; dried in the violet

of the sun’s antibiotic, buffed to a glow

then stowed in old newspaper for winter

in cardboard boxes under our parents’ bed.

Dad would lodge one apple in his pocket

when he left early for his industrial unit.

The rest were put to play: on Hallowe’en,

the children of the house would bob for them

(the apple being the prize). On Christmas Eve

they wound their way into toes of stockings,

scented by Laxton Fortune’s insulin tang,

past perfume of their being once alive.

By Easter, the boxes under the bed were bare.

Dad started dying in the eighth year

of the apples. Customs of cancer-care

could not cease mum’s raising of her trees.

Winter-washing; grease-banding; pollinating;

spraying; harvesting; pruning; tarring;

salt-cleansing; sun-drying; stowing; boxing.

Every act a clear concentrating.

The trees thrived. They began to improve on

my springing height because of her attention.

By the day dad was cremated, the trees

were out of control. My older brother

was also out of control. We lived in fear.

His arrest brought silence and a truce

because now it was only me and mum,

my sister having grown up and gone.

And the trees had grown beyond us both.

August was florid with a yield so vast

apples thudded sluggishly on slug-slick grass.

Blackbirds and thrushes, worms, larvae.

One tree’s care could take one longish day

and I was a teenager, ‘father of the house’.

Late-December, while they slept under snow

she hacked their trunks then tore the taproots free.

‘They were too much bother.’ She turned over

their bones in the snow-fire and stared past me

along the opened graves of her four trees.

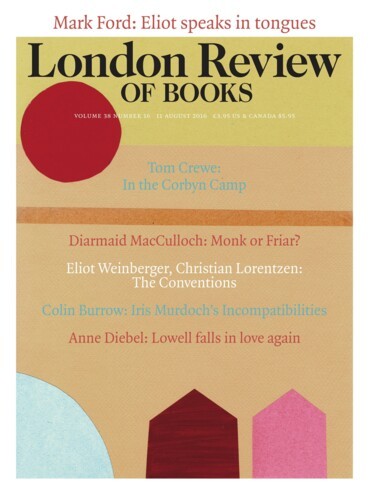

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.