The woman who cuts my hair – forty-something, old enough to remember punk but a neo-hippy these days – recently mentioned she’d been to see Patti Smith, who was touring her 1975 album, Horses, for its 40th anniversary. ‘Patti, yeah! Went to see her at the Roundhouse. Paid £30, which I didn’t think was too bad … Didn’t stay that long, though’ – snip, snip – ‘Went up the front and had a proper look, up close and personal’ – snip, snip – ‘And then I left early.’ This is fitting for a performer it’s almost de rigueur to call ‘iconic’. The price of entrance is paid to receive the benison of her holy presence, not to listen to the once volatile, trance-inducing music.

Smith (née Smith), who turns seventy this year, has had just one hit single (‘Because the Night’ in 1978, co-written with Bruce Springsteen) in forty years, and the only one of her 11 albums with an unassailable reputation is her glorious debut, Horses. I’ve known many people who dearly love Horses, but I can’t recall a single person ever declaring a passion for any of the other work, intermittent poetry and photography included. (If you type ‘patti smith lyrics’ into Google, five of the eight most popular songs are on Horses, and one is ‘Because the Night’.) For a while now, Smith has been the sort of feel-good, feels-real celeb who gets invited to ‘guest edit’ Vogue when the Dalai Lama is resting. But it’s hard to know how much anyone likes any of her post-Horses work, or what ‘popular’ really signifies in her case. Smith isn’t Bruce Springsteen or Beyoncé popular; but neither is she some divisive figure out on the blasted perimeter, like Scott Walker. Devoted fans prize her as one of our culture’s great ungovernable Outsiders. This fan club includes the grandees of the French establishment, who in 2005 named her a commander of the Ordre des Arts et des Lettres, making Smith about as much of an insider as it’s possible for an outsider to be. ‘Outside of society/That’s where I wanna be!’ she once bawled, in the lamentably titled ‘Rock’n’Roll Nigger’. This kind of earnestly meaningless rallying cry may be forgivable in the very young (or very stoned); Smith was 31 when it was recorded. ‘I’m pretty much unmanageable at this point,’ she claimed in a 2002 New Yorker profile. The same profile went on to detail a full itinerary of gigs and poetry readings, a big new official retrospective CD, new books, the continuing sales of Horses etc.

Horses is one of a handful of punk-era albums that people still listen to, and find stirringly polyvalent. It’s difficult now to capture just how wild and singular it felt when it came out. Smith crumbled scores of unspoken barriers just by being herself: spiky, garrulous, unguarded. The Robert Mapplethorpe portrait on the album cover – a deceptively simple monochrome shot – dared each viewer to find his or her own take on its sibylline RSVP: this is who I am, take it or leave it. If you were a young woman looking for a sympathetic figure to embody various inchoate feelings, the choice at the time was almost non-existent. Smith was a tiny echo from the future. White shirt, dark hair; white background, dark eyes; tiny white equine jewel, dark tie; hands in a cagy gunfighter’s arch over her wide-open heart: this hauntingly simple image anticipated so much to come in fashion, and helped launch a whole new pared-back aesthetic. Watch any BBC4 repeat of Top of the Pops from the mid to late 1970s and it seems inconceivable that the Smith of Mapplethorpe’s photo belongs to the same blithe, peppy era. She seems more real than the crinkly tinfoil stars of the time, but also a thousand times more fantastic. Think of all those 1970s prog rock sleeves and their multicoloured worlds of sauciness and sorcery – then switch to the stark monochrome field of Horses, and other images waiting in the wings: Richard Hell, Iggy Pop, the Ramones. It really was, as the old cliché has it, that black and white.

There was no commando unit of primpy stylists for Smith in 1975 – just her, Mapplethorpe and (as related in her 2010 memoir, Just Kids) a few quick shots one afternoon as the New York sun began to dip. One of the reasons the resulting image was so powerfully unnerving was the absence, back then, of any readymade ideological syntax with which to parse the experiment. (I don’t remember hearing anyone use the phrase ‘empowering’, say, until at least 1980.) Smith – rumpled, haughty, Sinatra-jacket thrown over her boy-shirted shoulder – was just oddly, naggingly sexy at a time when rock/pop was distinctly low on sexy. If you were a teenager in the 1970s you were always being told by previous generations that sex was the very essence of rock’n’roll – but sometimes you had to wonder. An arthritic Chuck Berry on TotP, slobbering the playground snigger of ‘My Ding-a-Ling’? Rod Stewart jiggling his satiny wee buttocks like some bored old burlesque artist? Any of this doing it for you, kids? The backroom intimacy spotlit by Mapplethorpe and Smith looked deeply subversive, but had none of the usual tawdry appliqué of ‘erotica’: its power emanated from one woman’s gaze and its implied sensibility.

Horses mixed rock’s air of priapic heroism with the plain aromas of everyday life. Many of the album’s lyrics concern the small sadnesses and victories of family, friendship, love, but they never seem solipsistic. Smith took a handful of favourite 1960s 45s – ‘We Like Birdland’ by Huey ‘Piano’ Smith, Chris Kenner’s ‘Land of a Thousand Dances’, Them’s ‘Gloria’ – and magicked their trashy pop into convincingly ecstatic art music. She threw a block party at which a straggly line of unlikely scenes (1960s garage rock, Warhol’s Factory stars, the gay S&M underground) could finally flirt with one another, outrageously. She found fresh and unlikely sources of fuel for the traditional rock’n’roll gnosis of dance, deviance and drugs. She didn’t want to end rock’n’roll, she wanted to shake it back to life. Horses mimics classic 1960s pop-rock before its larky brashness got lost in earnest philosophising. I see the young Ray Davies – an ambiguous girly-boy who hymned his cheap-suit backstreet bohemia over blackout power chords – as Smith’s John the Baptist. Horses betrays a love of early Kinks, Them, Who, but reframes their riffy aesthetic with studied artfulness. How much credit should go to the producer, John Cale, isn’t clear. Smith never sounded this weightlessly witchy and lustful again. It’s surely no coincidence that the same thing happened with another artsy New York chanteuse: Cale’s productions for Nico were similarly intimate and askew, while left to her own devices the German diva’s default setting was a one-dimensional gothic mope. Gossip suggests that there were big disagreements between Smith and Cale during the recording of Horses, and in Just Kids he’s the only wild boy from that time who doesn’t get his long-overdue gold star.

For its awed young audience, Horses was a noisy firework inauguration; for Smith, it pretty much announced the end of an era. She had developed her work from the end of the 1960s and through the 1970s inside a small protective circle of New York friends: no pressure, no deadlines, all the time to rewrite in the world. She could experiment with how much to reveal, what to mythologise, how far to dare, how loud or quiet to read, what to hold back. One of the reasons Smith sounds so confident on her debut is that she had been working on it for years. The unforgettable intro of the opening song, ‘Gloria’ (‘Jesus died/for somebody’s sins/but not mine’), began life as a long, barely punctuated text from 1970 originally titled ‘Oath’, and later ‘In Excelsis Deo’, as she confirms in Collected Lyrics 1970-2015. If these spooky proclamations don’t sound like your average 1970s rock song it’s partly because they didn’t start out as rock songs. They started out as poems, or as the kind of avant-garde-lite poetry in vogue at the time. No capital letters, ‘w/’ instead of ‘with’ and ‘thru’ instead of ‘through’: Emily Dickinson via Charles Bukowski; Artaud and Bataille laced with American me-first and can-do.

Like many rock acts, she’d had years to dream up her world-shut-your-mouth arrival, then suddenly had no time at all to patch together a follow-up. Only ten months on from Horses, the second album, Radio Ethiopia (1976), felt as flat-footedly wrong as Horses felt uncannily right. It was merely a huge disappointment at the time; today, it’s almost unlistenable. Where Horses was warm and lively, Radio Ethiopia is curdled and flat, with standard verse-chorus-verse songs, conventional screechy guitar solos and baby-talk ‘raps’ that wouldn’t have disgraced the beatniks in It’s a Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad World. ‘I move/in another dimension!’ is her unconvincing boast. She sounds blocked-up, whiny, nasal, as if she’s singing from the bridge of her nose. ‘Ain’t It Strange?’ another track asks. Horses just was irremediably strange, off in its own world of dappled otherness; it didn’t need any call and response confirmation.

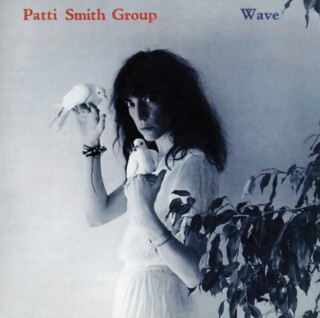

By 1978’s Easter, her once inimitable sass had been distilled into listless platitude. A boilerplate song title like ‘High on Rebellion’ invites the response: ‘Er, as opposed to what? Complacency? Neoconservatism?’ It’s as if she feels she has to offer a new, larger audience her stadium-rock bona fides. Compare the sleeves of Horses and 1979’s Wave (also by Mapplethorpe): Horses is cool and uncluttered; Wave is the rock’n’roll equivalent of one of those wacky ‘You Don’t Have to Be Mad to Work Here but It Helps!’ signs: bulging ‘I Say, Is This a Drug Fiend?’ eyes, and (oh, dear) Two Symbolic Doves. (My hypothesis at the time: the sweet intimacy of Smith & Mapplethorpe now had a third partner whose name was Too Much Cocaine.) Smith is still referring back to the 1960s canon, but all the fun is gone: she now provides study notes. Of the 1967 film Privilege she writes that it ‘merged the rock martyr with all the sacristal images of the 1960s … the cross … the Christ … the whip and the lashes that served to veil velvet weeping balls’. She mated a song from Privilege with the 23rd Psalm, and it stalled at 72 in the UK singles chart. Horses let us explore all its secrets on our own; now everything was spelled out in advance, via references to Easter, communion, psalms, fighting the good fight. (Were you by any chance brought up a Catholic, Patti?) Over droningly portentous church organ she hymns ‘the nights of rock’n’roll’, and is possibly the only person in rock’n’roll who could have made the line sound more like crippling penance than sweaty celebration.

Pretentiousness per se wasn’t the problem. The problem was that, trapped inside her new giddy-up music business schedule, she hadn’t had the time to explore any fresh ways to be pretentious. By day she posed for photo opportunities, sprawled in front of a French graffito that read ‘L’ANARCHIE’; by night she dined at glitzy high-society tables. But it was precisely because she was so different from the grubby rock’n’roll norm that she had been so wildly attractive to many of us. Rock? Rock was musty old guys in dank pubs flogging paunchy old riffs. But we’d misread her: she worshipped those musty old guys. In 1978, a tender acolyte, I attended a press launch at the ICA for the British publication of her poetry collection Babel. (My first press launch! My first book review! My first feather-cut rock’n’roll heroine in the flesh!) My memory is that she was wearing a greyish white T-shirt adorned with a Nosferatu-like image of Keith Richards. Before the assembled hacks, she launched into a risible stream-of-consciousness rap – a dithyramb to all the Keefs and Bobs and other venerable rock’n’roll patriarchs. I wanted a polysex pop music Kali, and here she was dragging it all back down to earth again, like an over-excited fan club secretary on too many diet pills. Bored and embarrassed (and quite probably on too many pills myself), I raised my schoolboy hand and said that – speaking for my own constituency of self-important young punks – all this grievous old rock’n’roll baloney was, like, strictly for the old people’s home. Instead of taking offence at my point of order, Smith seemed instantly smitten with my pale, malnourished UK gall and, oh my god, is she actually flirting with me? It would be many years before I felt able to approach Horses again. On YouTube there’s plenty of similar stuff from that time: Smith unflaggingly humourless in her own New Yawk-bohème version of Spinal Tap. (Favourite quote, to a puzzled Swedish interviewer: ‘I’m a nigger of the universe!’) She turned her non-stop round of touring, press conferences and snatched recording schedules into a fanciful turn of phrase – it was all, she said, the necessary slog of being in her own ‘rock’n’roll army’.

In 1980, she married another rock’n’roll lifer, MC5 guitarist Fred ‘Sonic’ Smith, and together they took a long time-out from the music business. They settled just outside Detroit and had two children. They released one album together, 1988’s Dream of Life. Her new book, M Train, makes this time sound like the period when life and dream merged for her, indissolubly. You get the impression her slightly more grounded partner brought her back to her senses, showing her that ordinary back-garden life could be a source of alchemical gold, too. Then, in 1994, Fred Smith had a massive heart attack and died, aged just 45; her brother Todd died unexpectedly soon afterwards. Robert Mapplethorpe had died in 1989, after complications arising from HIV/Aids; Richard Sohl, the pianist in the Patti Smith Band, had died of a heart attack aged 37, in 1990. Anyone might have been floored by such a cruel turn of events, and friends encouraged Smith to return to music as a way of coping. Grief became entwined with songwriting. She wrote about Kurt Cobain in ‘About a Boy’, and elsewhere referenced the deaths of two of her mentors, William Burroughs and Allen Ginsberg. The sleeve of Gung Ho (2000) was the first not to feature her own portrait, replacing it with an old snapshot of her late father. She seemed to be securing some kind of future by assessing her past (a not uncommon manoeuvre in middle age, even among non-artists). When Just Kids, the memoir devoted to her life-changing relationship with Mapplethorpe, came out in 2010, many readers, myself included, were pleasantly surprised by a new turn in her writing: there was far less straining for wild ‘poetic’ effect, and far more delight in the joys of everyday life.

For the most part, M Train continues in this vein. It reads like the work of someone who has learned to trust her instincts, telling us what she genuinely takes pleasure in rather than what she thinks she ought to be seen referencing. Even if some traces of the old googly-eyed boho persona remain, she seems to have realised she is not duty bound to put on a grand show of seamy decadence when that is not really (or not always) who she is. (She also seems to have found a good, old-fashioned, no-nonsense editor; neither M Train nor Just Kids has the longueurs of many other rock memoirs.) It’s no use pretending your life is all Verlaine and Rimbaud when you’ve mostly been raising a family in suburban Michigan. Once her diaristic poem-texts let us in on her ‘urge to shit voltaire style’; now we get Our Lady of the Cat Litter Tray. A typical diary text of old was: ‘i rummage thru the closet. it takes a long time, but i finally find what i am looking for. a sack of red skin.’ Now, she tells us she spends her days sprawled in front of ITV3 for (hooray!) all-day binges of Inspector Morse, Cracker and A Touch of Frost.

Husband deceased, children grown, house empty (or at least that’s how she portrays it: this propagandist of la vie passionnelle tells us zero about her own sex life), she sustains her spirit on a drip of caffeine, stoical TV detectives and old and new books. (The one thing I don’t remember surfacing in M Train is music; you’d never know it was her day job.) Having decided to step outside the trademarked outsider role, she is an infinitely better writer. In a one-paragraph description of her father, early on in M Train, he comes completely alive: a real person, not a half-convincing plaster saint. For the first half of the book she pulled me right into the fidgety rhythm of her world. I really warmed to her. (How couldn’t I? Talking to cats, watching Inspector Morse repeats, reading Anna Kavan? She’s stolen my life!) If M Train had stayed there, as an unlikely TV addict’s pillow book, I would have been wholly won over.

In her 1979 song ‘Dancing Barefoot’, Smith sang of ‘grave visitations’. If we take M Train at its word, Smith now seems to spend half her life conducting a strange form of mourning pilgrimage – a boho death cruise – visiting the graves of writers, artists and other visionaries. She tidies up their cemetery plots, takes blurry Polaroids, meditates, sometimes takes home a mnemonic twig or pebble. She’s obsessed with objects that were once owned, or simply touched, by other artists (Hermann Hesse’s typewriter, Robert Graves’s straw hat, Margot Fonteyn’s ballet slippers). Virginia Woolf and Frida Kahlo are on her itinerary, but you get the feeling she’d have no problem with a canon largely comprised of dead (cool) white guys; strangely, or possibly not, in both Just Kids and M Train other women are largely absent. It’s not just that rock’n’roll in general, and the Patti Smith Band in particular, is a very male affair, or that Smith likes metaphors about boys’ gangs and boys’ things; deeper down, on some murky psychological level, she sometimes comes across as though she takes herself for a special exception that proves the boys’ club rule. (If you were a certain kind of a shrink, you might wonder if it’s mere coincidence that when she finally got married, it was to someone also named Smith.)

M Train is a self-portrait of the artist in late middle age, and it’s to her credit that she includes most of the everyday stuff other rock stars are usually afraid to mention. She potters, stares out of the window, does the laundry, reads; she buys, makes and thinks about coffee. (There’s a lot of death and coffee, but no sex or taxes.) This is not the ageing rock star à la Keith Richards or Lemmy, maintaining the gnarly crocodile-skinned persona to the bitter end. But though she gives the impression of spilling the (Arabica) beans, there are also signs of something more ambiguous – details that make you distrust the performance of homeyness, or least take it with a pinch of artisanal honeycomb. There is, for instance, her membership of something called the CDC or Continental Drift Club, which (allegedly) holds semi-annual conventions in places such as Bremen, Reykjavik, Jena and Berlin. ‘Formed in the early 1980s by a Danish meteorologist,’ she explains, ‘the CDC is an obscure society serving an independent branch of the earth science community. Twenty-seven members, scattered around the hemispheres, have pledged their dedication to the perpetuation of remembrance specifically in regard to Alfred Wegener, who pioneered the theory of continental drift.’ Reviewers seem to have taken this at face value, but even if such a strange little cloistered society did exist, why exactly would Patti Smith be asked to join? Note the ‘dedication to the perpetuation of remembrance’: is our allegorical leg being pulled here just a bit? And is it just coincidence that nestling in her book bag are authors such as W.G. Sebald, César Aira, Haruki Murakami, Roberto Bolaño, Enrique Vila-Matas and others, writers who purposively smudge the line between memoir and fiction? M Train, with its dot-dash series of woozy photographs, even looks like a Sebald text, and I got the same queasy feeling from it that I’ve often had reading him: half-admiring, half-sceptical; almost seduced, but finally left cold. As with a flawless magician, you know there’s some form of misdirection going on, and it chips away at your pleasure in the performance. (I was annoyed at myself for assuming her visit to a ‘place called Café Bohemia’ was some kind of wink-wink sign, when it’s also a fairly common name in Mexico, where she happened to be.)

The spell-casting mood of M Train demands that Smith fly off on a moment’s whim, spurred on by nothing more than a lovely line in a new book she’s picked up: she realises she loves Writer A, who either lives or is now buried in City B, decides she has to be there NOW, and before you know it she’s graveside again, the Intercity angel of death in dark Helmut Lang pants and Ann Demeulemeester cloak. It’s all so smooth and hassle-free it could be a 1980s edition of the old BBC Holiday programme. While Smith certainly wouldn’t give Mariah Carey anything to worry about in the diva stakes, she is still a well-known rock star, and this is definitely not global travel as most of us experience it. In the late 1970s, Smith’s path crossed with another mysterious traveller, Bruce Chatwin, who was part of the same moneyed, arty, cross-continental gay set as Mapplethorpe and his patron/lover Sam Wagstaff. There are things in M Train that niggle at me in the same way Chatwin’s work often did: the feeling that for all their much vaunted ‘realism’ these treks occurred in a rather privileged sphere. There’s always a rich pal to provide a bed, a dinner table, a handy castle to stay at for the season; there’s always someone in the background to make sure the plane tickets arrive; fresh figs on the bedside table. Special people, living by special rules. Like Chatwin, Smith is also a bit of a consumer fetishist: the simplest things have to have a special aura or signature – or, let’s get real, a high-toned brand name. It has to be a certain Moleskine notebook. The pencil has to be Conté. The ink has to be from a little shop no one knows in the backstreets of Florence. (Full disclosure: like many writers, I too work with a special favourite pen – it’s a freebie from my wife’s West London dentist’s.)

For the first half of the book, she had me: I happily surrendered. It was only when I got to the chapter featuring two people whose work I happen to know and love, Paul Bowles and Jean Genet, that the spell was broken. All of a sudden, this oddfellow’s odyssey didn’t feel quite so whimsical – it felt borderline exploitative, as though she was using these people, or their memory, to make herself look good. Bowles was sort of interviewed by Smith, just before his death in 1999: he was obviously not in great health, and she has nothing new or diverting to report about the man or his work. The episode as related skirts bad taste, and serves only to show Smith in her best light, as a sensitive literary pilgrim. (Just like a character in one of Bowles’s novels, in fact: one of those wan American travellers who stumble around North Africa looking for the light of revelation, when the occupants of the countries they flit through are looking merely to survive.) Earlier in the book, she and Fred Smith travel to far-flung French Guiana in order to pick up a commemorative pebble in the ruins of a French penal colony for the similarly ailing Jean Genet: ‘I envisaged bringing him its earth and stone.’ As with Bowles, at the time of this jaunt Genet was dying, refusing pain medication in order to finish Un Captif amoureux. She says that in his early work Genet painted earthly hell-holes as his own form of secular redemption, and that when they disappeared (and he was pardoned) he was in some sense ‘denied entrance into … paradise’. But later in life, Genet was apt to dismiss such talk, warning fond interviewers not to take it all so literally. Only an idiot would want to stay in prison! (‘For me, it seems that, since all my books were written in prison, I wrote them to get out of prison.’) My feeling is that Genet would find all this stagily literal Literary Pilgrim stuff absolute hooey, and contra the kind of old-fashioned existentialist values he held dear: live in the future, not the past, and never dwell on old glories or regrets.

Is it fanciful to detect in M Train the odour of sanctity mingled with that of the sickroom? Does Smith see these strange journeys as improvised versions of last rites for her literary heroes? Where the fiction (and reportage) of Bowles and Genet is streaked with the immanence of sheer horror, Smith’s own quest tends to near kitsch. What saves M Train from terminal whimsy is the presence of her late husband – spectral but solid, the beer-and-football yang to her slightly scatty yin. When Smith eulogises Lennie Briscoe, a character from the American cop show Law and Order, you don’t have to be Jung to realise there’s something going on between the lines: bit of a drinker (or ex-drinker), old-fashioned guy’s guy, a straight arrow. The same qualities apply to both Fred Smith and another evanescent presence here, a strange and not entirely convincing ‘cowboy guru’ figure who bears a close resemblance to Smith’s mid-1970s ex, Sam Shepard.

The cover flap of M Train quotes Smith’s own description of the book as ‘a roadmap to my life’, and that’s how it has generally been reviewed – as a continuation of the tenderly recuperative Just Kids. But it could also be read as a cautionary tale about the frail reassurances we seek in remembrance, about nostalgia as a borderline fugue state. You can take all these great, hungry leaps out into the wider world – of course you can – but they also ensure that you are always coming back home again. As with Just Kids, one of the first things you notice about M Train (and Collected Lyrics) is that everything is tastefully monochrome, full of pasted-in samples of Smith’s handwriting, blurry Polaroids and other memory trails. (She seems obsessed with patina everywhere but in her music, which has the texture these days of thin and unadventurous Adult Oriented Rock.) Fans might see this trompe l’oeil scrapbook effect as a nice personal touch in a world of mass downloads; I couldn’t work out why it annoyed me. Eventually I realised it was because she wants even her photography to look as if it belongs to the past. She turns images of the jagged present into veiled mementos of a vanished yesteryear. There’s something of this, too, in the way she transforms low-life cruisers like Rimbaud and Mapplethorpe into virtual saints, with all the stink and bedlam of their wild ride erased. Francis Bacon minus the screams, Genet without the cocks, Bataille sans the mad laughter.

The pair of Mapplethorpe’s slippers that Smith has shown under glass in recent years (part of shrine-like exhibitions comprised of favourite and significant objets), look to most of us like nothing more than a pair of slippers – albeit quite spiffy ones. They don’t mean anything special to us because the owner wasn’t anyone special to us; he certainly doesn’t mean to us what he means to Smith. Everything she says about him has to be taken on trust, since from the evidence of his work (and Patricia Morrisroe’s eye-opening biography) you get a rather different impression: that of a distinctly un-spiritual man, cold, aloof, a manipulative careerist. You might even argue that if or when his images work, it is because they insist not on the joyously spiritual but on a darker and contrary message: this is flesh, it is nothing else. Mapplethorpe was an artist driven by carnal furies, which is not something you’d ever say of Smith. She’s too, well, nice; our own trendy rock’n’roll vicar. Robert’s monogrammed slippers rest snugly in their vitrine, like yellowing knuckle-bones in a gold-leaf reliquary, all the will, swill and semen behind his art and life deodorised away. In many ways, Smith is still the teenage Patti Lee, who stuck texts and pics and reproductions on her New Jersey bedroom wall in a crazy-paved collage of British Invasion pop, Catholic symbology and European art: saints and sinners and sexy English singers. She’s a soul collector, still indulging her artsy teenager’s habit of assuming the implied persona of every new enthusiasm, be it Virginia Woolf, Edie Sedgwick or Joan of Arc. Unfortunately, this risks turning fraught, painful lives into kitschy trinkets, designed to lend the wearer profundity by association.

Doesn’t the deeply ingrained habit of starstruck homage sit uneasily with her occasional Mother Courage posturing and blowsily libertarian, anarchist-lite politics? In a 2003 interview, she described herself as ‘essentially a late 18th-century, early 19th-century kind of person’, and went on: ‘There is a part of me that likes to serve the people. In a different era, I’d have liked to have worked with Thomas Paine.’ A pretty infallible rule of rock thumb is: anyone brandishing the word ‘people’ (there was also her 1988 song, ‘People Have the Power’) no longer considers themselves one of the people, and probably hasn’t for some time. Smith has always seemed to have conceived of rock’n’roll as a particular and solemn form of donning the veil. In the New Jersey childhood described in Just Kids and M Train, her future mission was already apparent. She discovered her armour early on: the pre-adolescent Patti was already ‘the commander of a small but loyal army’. Even at play with her sister and brother, Linda and Todd (‘our faithful knight’), she betrayed a messianic transport: ‘Our cardboard shields were covered in aluminium foil and embellished with the cross of Malta, our missions blessed with angels.’ ‘I secretly identified with Davy Crockett,’ she confides, though it’s unsurprising by this point, because there doesn’t seem to have been a single book, performer, archetype or cartoon character she didn’t in some way ‘identify’ with. Here are just some of the people and things she wanted to be: James Brown, Jo from Little Women, JFK, Rimbaud’s girlfriend, ‘the mistress of a great artist’. ‘I wanted to be Johnny Carson’s successor,’ she says, ‘that’s what I dreamed of. Not of being the next Jim Morrison.’ Did any child, however precocious, ever dream of being Johnny Carson and James Brown and Modigliani’s mistress and Patty Hearst and Thomas Jefferson? Did all these assumed roles co-exist daily? Did they ever get mixed up? She’s often portrayed as one of life’s eternal naifs, but she has a suspiciously handy way with a pull quote. She mentions going to see John Coltrane as a kid, and then you notice – sheer coincidence – that the most unlikely comparisons to Coltrane and Ayler start to crop up in reviews of her post-Fred music, in reality a rather plodding, pro-forma rock. Is all this real or is it shtick? Is there any meaningful difference?

Towards the end of Just Kids Smith writes:

I had explored ideas that Robert and I often discussed. The artist seeks contact with his intuitive sense of the gods, but in order to create his work, he cannot stay in this seductive and incorporeal realm. He must return to the material world in order to do his work. It’s the artist’s responsibility to balance mystical communication and the labour of creation.

Most readers probably glide over this sort of old-school Nietzsche/D.H. Lawrence boilerplate without it really registering, but there’s no question Smith herself takes it seriously, always did. There have been clinches with Catholicism, Buddhism, paganism, you name it, but Art is the one thing Smith has never stopped worshipping. By the mid-1970s, setting out to be the kind of romantic, bohemian figure Smith revered was already a specialised form of indulgence. It was too late to dedicate her art, as Baudelaire once did, ‘aux bourgeois’, and what is a bohemian without a bourgeoisie to shock? This is Smith’s core dilemma: she was too late to be a real bohemian, and too flagrantly sincere to make a provocative postmodern play of it. Forty years on from Horses, today’s bohemian hipsters are the new bourgeoisie: they have beard dialogues, coffee hobbyist mornings, oh so many petitions to sign, even an equivalent of that dread 1970s ‘Do you want to see our holiday slides?’ moment up on Instagram. It is they who now move into the kind of dilapidated prole areas Walter Benjamin and the Situationists once hymned, only to gentrify them with … the funky little coffee shops Patti Smith hymns throughout M Train.

If M Train is a kind of celebrity psychogeographica, it’s one that old-world bohemians like Rechy, Genet or Burroughs would have a hard time recognising. Smith’s wish-upon-a-star bohemia is all in her head, or up on her bookshelves. It doesn’t, it couldn’t, exist out in the workaday world: the rents are too high, and social media is too quick to smother the first tender shoots of difference. The likes of Harry Smith, Robert Frank or Sun Ra (or indeed 1970s Smith herself) wouldn’t stand a chance of a slowly nurtured career in the New York of today. M Train is fixated with the mourning process one case at a time, but there is surely cause for a wider social mourning that Smith doesn’t begin to voice or articulate. She was 15 in 1961, and her airy worldview is anchored in that time: it’s a mix of cool beatnik empathy, early rock’n’roll hysteria and (still) the idea of those supernaturally funky folks on, uh, the dark side of town. (Don’t get me started on her rap about how she learned to dance with all the funky ‘spades’.) T.S. Eliot once said of Baudelaire that he was ‘in some ways far in advance of the point of view of his own time, and yet was very much of it, very largely partook of its limited merits, faults and fashions’. Virginia Woolf said of another great street philosopher, Thomas de Quincey: ‘He shed over everything the lustre and the amenity of his own dreaming pondering absent-mindedness.’ So it is with Patti Smith: you just have to take the rough with the smooth. She is great at reminding us all of our own youthful dreams; it’s just a whole lot tougher to make them coincide with reality these days than she suggests.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.