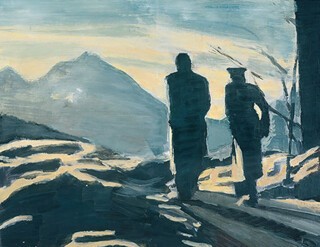

Luc Tuymans’ s painting The Walk shows Hitler and Speer silhouetted in early evening light on the Obersalzberg. The photograph that the painting is based on is mute. Tuymans’s manipulation of it is anything but. His Hitler, the Führer, the guide, is indeed guiding, just. He is stumbling awkwardly towards the last of the light while the upright Speer holds back, following certainly, but cautiously, tentatively, allowing his idol and besotted patron first dibs on divining the future – which may prove to be less golden than the sun’s shafts seem to promise. What if the guide has lost his touch, can no longer read the entrails? Speer’s detachment and poised ambiguity were not entirely affectations. He was a provincial snob who regarded himself, with cause, as socially superior to Hitler, let alone such freakish botches of Aryan manhood as Himmler, Göring, Ley and Goebbels.

It was easier than he expected for this aloof, offhand man to escape the scaffold at his trial by dissociating himself from the milieu at whose centre he had been for more than a decade while smoothly inculpating his fellow denizens. There was nothing about his mien which suggested fanaticism or a capacity for grotesque cruelty. His appearance belied his ruthlessness, occluded his indifference to the terrible suffering he caused, masked his absolute bereavement of imagination: he possessed a near sociopathic absence of empathy, a careless incapacity to understand the consequences of his orders. He was actorishly handsome. This somehow rendered plausible his barely credible expressions of ignorance, it gained him the benefit of the doubt, it supported his preposterous claim to be a morally neutral artist and technocrat rather than a mere armaments minister and slave-driver.

Speer was lucky not just in his looks. His life was a succession of felicitous opportunities which came his way without obvious effort. Of course he strove to make his luck. But he had too great a sense of entitlement to allow himself to be seen to scramble for preferment. He gave the impression that he was the insouciant recipient of chance’s beneficence. He was, however, genuinely lucky to be rejected as a student by the great Expressionist Hans Poelzig. He was obliged to study, initially reluctantly, under the super-twee Heinrich Tessenow, whose precursively völkisch, Arts and Crafts saccharine he was indifferent to, even though it would become the almost invariable idiom of bucolic settlements, agrarian expansion and, on a larger scale, of the Ordensburgen and Napola – schools for the Nazi elite. Unastonishingly, Tessenow was keenly anti-modernist, going on Luddite. Speer was impressed. He acquired a cast of mind and a gamut of tastes which would soon allow him to ingratiate himself with Hitler, whose ranting in a Berlin beerhall prompted him to join the National Socialists in January 1931, two years before they seized power. During that period Speer became, faute de mieux, the impecunious party’s interior designer of choice. His initial willingness to work without a fee eased his way. He was also lucky enough to be the only party member in Wannsee who owned a car, a prized asset during the constant electioneering and manifestations of that time. His first client was the future SS general Karl Hanke, then a local party organiser. As soon as the NSDAP was in power he received a further commission from Goebbels. Which in turn led to what would be the first step towards the mise en scène of the Nuremberg rallies, a May Day 1933 mass meeting at Templehof decorated with flags the size of sails and illumined by searchlights.

Tessenow slighted Speer: ‘All you have done,’ he said, ‘is create an impression.’ The derision was prescient; such was the sum of Speer’s artistic gifts. As much as anyone he created the potent decor and ritual choreography of this most façade-obsessed regime. He was less an architect than a Busby Berkeley with a penchant for Black Masses. It irked him that the ‘immaterial’ light-shows at Nuremberg were reckoned his greatest achievement. In Spandau Prison, with time on his hands to rewrite history over and again, he deluded himself that he would have produced a work to match the Parthenon had he not been appointed minister of armaments. But when he was offered the post he had accepted with indecent alacrity.

This was the second job he owed to luck’s efficacy in removing obstacles. Before Hitler fell for Speer, the leading contenders for architect laureate of the Third Reich were Paul Schultze-Naumburg and Paul Ludwig Troost. Schultze-Naumburg was the author of the Cecilienhof, where the Potsdam Conference would be held. He was also the author of Art and Race, a sniffer-out of degenerate art, an opponent of corporatism and decorative excess. His friend the racial theorist, eugenicist and future ill-fated minister of agriculture Richard Walther Darré wrote Race: The New Nobility of the Blood and the Soil at his estate near Jena. Both belonged to the primitive, woodworking, neo-peasant, maypole-hugging ideological left of the NSDAP, in which broad church they were about as distant from Speer as it was possible to be.

Schultze-Naumburg was unquestionably an architect. Troost was an interior decorator. Much of his career had been devoted to blinging the state rooms of Norddeutscher Lloyd liners. Yet, as Despina Stratigakos observes in Hitler at Home, Hitler considered him ‘the greatest architect to grace German soil since Karl Friedrich Schinkel’. Most members of the German architectural trade had, during the Weimar Republic, turned to international modernism or Expressionism. Hitler was hardly spoiled for choice among the remaining revivalists. Gerdy Troost, who had his ear, rarely failed to excoriate her husband’s rivals. She appears single-handedly to have engineered Schultze-Naumburg’s fall from favour in revenge for a catty comment made after her husband’s early death. Learning that she was going to continue Atelier Troost he remarked: ‘I would not let a surgeon’s widow operate on my appendicitis.’

The beneficiary of these spats was Speer, the court favourite without portfolio who surefootedly negotiated the labyrinth of Nazi high command. He hardly needed to remind his many antagonists of his special relationship with Hitler. He was untouchable. Like his peers he built a kleptocratic empire within a larger kleptocratic empire. That was what was done. The boundaries of ownership between state, party and private interests were wittingly blurred. Procurement was haphazard. Agencies duplicated one another. Departments were perpetually engaged in internecine strife. Speer acquired the ability to convince himself that what he knew to be mendacious propaganda was true. This was a quality he shared with Hitler, may even have learned from him. He knew better than to burst illusion’s bubble. Until almost the very end he fed his patron a diet of welcome lies. The truth was neither to be accepted nor imparted. In this Speer was at odds with his predecessor as minister of armaments, Fritz Todt, whose pessimistic candour may have cost him his life. In Joachim Fest’s estimation, ‘his sense of reality particularly distinguished him in Hitler’s entourage.’ He had been in the habit of telling Hitler what Hitler didn’t want to hear, specifically that the war on the Eastern Front was unwinnable. A dictator’s Weltanschauung is necessarily not that of even his grandest minions; it is not an empirical construct susceptible to challenge or correction.

Todt died when his apparently sabotaged plane crashed on take-off from Rastenburg, where Hitler had his eastern HQ. Speer, en route from Russia, had happened to drop in unannounced the previous day, anxious to see Hitler after a gap of a few weeks. He was offered a place on Todt’s flight to Berlin but, having talked long into the small hours with Hitler, declared himself too tired to travel. Within hours of Todt’s death Speer succeeded him. It all seems remarkably neat. The inconsistencies of Speer’s accounts of the crash and his reaction to it multiplied with every telling. Whether he played any part in what was effectively an assassination has never been established. And, among the cannibalistic elite of the Third Reich, there was no shortage of persons anxious to be rid of Todt.

Speer’s earliest war crimes were largely restricted to evicting Jews from properties that Nazis coveted or which might provide shelter for bombing victims. He also effected the demolition of many homes to make way for the bloated white elephant of Germania, Hitler’s new capital. These clearances were paltry put beside the consequences of his work on concentration camps. He had no part in running them but it was part of his brief to get them built, to quarry and fire the materials. He was close to Himmler and enthusiastically subscribed to the Reichsführer SS’s dauntingly simplistic policy of Annihilation through Work. Those worn out by labour on such projects as an autobahn through Ukraine were executed. Those who survived ‘must be treated appropriately, since by the process of natural selection they would form the kernel of a new Jewish resistance’. The childish brutality of these measures hardly accords with the persona burnished during Speer’s long lucubrations in Spandau. A persona that has had a toxic appeal for a particular sensibility: gullible, cheek-turning, risibly generous, smugly liberal.

Martin Kitchen does not possess that sensibility. Speer: Hitler’s Architect is not a biography. It is a 200,000-word charge sheet. Kitchen is steely, dogged and attentive to the small print. He shows Speer no mercy, nailing his every exculpatory ruse and demonstrating time and again how provisional the notion of truth was to him. This was a man who persistently invented and reinvented his past. His memory was biddable. He was clever in gauging the weight of guilt he would admit. He was certainly not so crude as to attempt entirely to exonerate himself: he calculated the degree of ignorance he could profess of this or that enormity. He differentiated between what it was known that he knew, what he knew, what he might have been expected to know, what he suspected, what was rumoured, what was kept from him, what was in the archives and what was not. This was, not that he acknowledged it, a game of his devising in which he toyed with a series of mostly awed apologists, interlocutors, historians, biographers, journalists, psychologists and groupies – who always lost.

They failed to rumble him as many of his colleagues had begun to in the Reich’s death throes. Goebbels had his measure. He wrote: ‘I don’t believe Speer any more … he makes up for the missing airplanes and tanks with phoney statistical fairy tales.’ Joachim Fest and Gitta Sereny were less willing to see through him. Fest deliberately overlooked material that was presented to him because it failed to accord with his conception of his subject. Sereny was unhappily predisposed to believe the best of anyone. Kitchen notes that her studies of Mary Bell and Franz Stangl show ‘considerably more sympathy for the perpetrators than for their victims’. His work is not, however, untainted by that of his predecessors. He blithely concurs that this ‘hollow man’ (oh dear) was ‘highly intelligent’. Here, once again, we are treated to the received idea of Speer, an assertion made in defiance of all that is now known about him. The grandly titled ‘theory of the value of ruins’ is hardly the conceit of a highly intelligent man. It is merely a truistic observation that an empire – the 12-year, four-month Reich, for example – will, many millennia hence, be judged by the ruins of its buildings. As Hitler said, ‘It is only through the art of building … that a political order can experience its most beautiful immortalisation.’

And what of Speer’s architectural intelligence? The remains at Nuremberg are tatty. ‘Beautiful immortalisation’ is not the description that comes to mind. But then it’s a stage without its players. The models of Germania (of which Andy Warhol and the Prince of Wales’s adviser Léon Krier were fans) indicate that the twin attributes of his buildings were laughable vastness and imaginative impoverishment matched only by the basilica at Yamoussoukro in Ivory Coast.

The title Hitler at Home promises an exciting war crimes edition of House and Berchtesgaden. It is actually an unfamiliar, diligently researched, illuminating account of the means by which a singular private and social life was invented. Stratigakos asserts that ‘scholars of architecture and fascist aesthetics have focused on monumental building projects and mass spectacle, overlooking the domestic and the minute.’ This is unexceptionable. But leaving aside the knotty business of whether National Socialism ought to be described as fascist, the academic disregard for its quotidian vernacular architecture, which is every bit as ‘representational’ as the grandiose set-pieces, is hardly going to be amended by scrutiny of the least typical domestic buildings in the Reich.

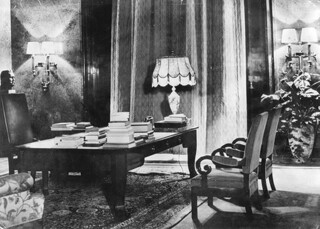

Until he was forty Hitler lived like a bohemian or a ragged student. He believed such an arrangement was electorally advantageous when the NSDAP’s appeal was chiefly to the working class. His move in 1929 to a large, expensive apartment in the Bogenhausen quarter of Munich was met with accusations of hypocrisy. His niece Geli Raubal’s suicide there provoked graver and more damaging newspaper coverage, in response to which he embarked on a vigorous PR campaign, bogus going on mendacious, which emphasised his normality and the modesty of his home life (by a dictator-in-waiting’s standards). After he came to power the Atelier Troost set about creating interiors that suggested respectability, solidity and propriety, qualities that ‘had nothing to do with a dangerous radical’. They were costly and dull. Gerdy Troost had the knack of second-guessing Hitler’s petit bourgeois antipathy towards anything that might be considered bad taste. He had a horror of kitsch and was capable of discerning it in the most improbable places. If the Berghof, his grossly distended chalet on the Obersalzberg, was decoratively understated it was nonetheless fitted out to satisfy a rich man’s infantile tastes. There was, for instance, a basement bowling alley. That, according to his valet, was the only exercise he took ‘except for the expander under his bed’, a detail that was unsurprisingly absent from the photographer Heinrich Hoffmann’s The Hitler Nobody Knows, with a foreword by Hoffmann’s son-in-law Baldur von Schirach, which mentions Hitler’s ‘library of six thousand volumes, all of which he has not just leafed through but also read’. Hoffmann’s volume set the sycophantic tone for dozens of others. Hitler the Yeoman Seer takes inspiration from mountains, he feeds animals, he holds hands with kiddies, he strides out with dogs (inevitably loyal), while Hitler the Photo Opportunist receives the world’s press in the sure knowledge that journalism feeds off journalism, that American Vogue can be relied on to publish gushing drivel that will spawn more drivel. The rather less vacuous Social Democratic paper Vorwärts wrote: ‘The great Adolf has spent the better part of his life having his picture taken … This is how Adolf has worked quietly for his people and satisfied their desire.’ It was closed down in 1933.

Among Hitler’s most doting fans was the Anglo-Irish devotee of Strong Men, William Fitz-Gerald (aka Ignatius Phayre), who wrote about his idol for, inter alia, Country Life, Current History and American Kennel Gazette, single-issue publications with a tenuous grasp of political morality and a mostly unquestioning readership. The note that Fitz-Gerald and many other dutifully credulous journalists struck was remarkably consistent and testifies to the manipulative efficiency of Hitler’s publicity machine. The same words recur: destiny, toil, youth, culture, music, authentic, sacrifice – oh the sacrifice. That publicity machine was also sedulous in courting useful idiots, none more useful than Lord Rothermere, who happened to own a newspaper and whose potential as messenger boy to the British establishment Hitler exploited, just as he exploited the New York Times Magazine, which on 20 August 1939 enthused about his love of chocolate and of gooseberry pie and his rapt attention to the petitions of ‘widows and orphans of party martyrs’. Plenty more of those presaged in the clouds.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.