Arriving at his prep school in the bleak winter of 1918 the ten-year-old Osbert Lancaster was made even more miserable than the average new bug by the fact that St Ronan’s, Worthing was a spectacularly sporty school. The headmaster, Stanley Harris, had captained England at football and was also a distinguished cricketer and rugby player. Lancaster, an only child who had lost his father two years earlier at the Battle of the Somme, proved himself as the terms came and went to be uniformly hopeless at every game. He might have cut a pathetic figure, but instead he began to display the unshakeable urbanity that would characterise him as an adult. A heartier contemporary from a local school remembered playing St Ronan’s at rugby. As he thundered towards him about to make a try, Lancaster did not move but politely inquired: ‘Do you wish to pass me on the left or on the right?’ The incident, which Richard Boston recounts in his biographical memoir of Lancaster, captures something essential about a man who, as a cartoonist and writer excelled in capturing types, human and architectural, yet himself remained hard to typify.

Pillar to Post and Homes Sweet Homes, the first two of these reprinted volumes, appeared in 1938 and 1939 and were described by Ernst Gombrich as comprising ‘the best textbook of architecture ever published’. The foreword or ‘Order to View’ of Pillar to Post opens with the sentence: ‘This is not a textbook.’ Like all great satirists Lancaster had his finger on the pivotal point at which irony occurs, when something is both true and not true to the same extent at the same time. Thus he immortalised much of what he criticised. ‘Bypass Variegated’ and ‘Stockbrokers’ Tudor’ have passed into the language; ‘Pseudish’ and ‘LCC Residential’, if less familiar, once seen are easily identified. The intention was to make readers realise, like the bourgeois gentilhomme discovering that he has been speaking prose all along, that everything built is architecture, ‘the cathedral, the dean’s house in the close and the public convenience in the market square’ and that anyone is entitled to have an opinion about it. Lancaster was no egalitarian, he mourned the passing of the upper middle class and the dwindling influence of the Anglican church, but he had the English dislike of experts and ‘the vast army of salaried culture-hounds’ who had introduced to Britain that hitherto exclusively foreign concept, the intelligentsia. Pundits, he thought, had fenced off the critical high ground with specialist terms until people were made to feel they couldn’t understand their own high street.

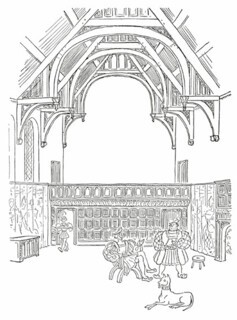

The books proceed chronologically and democratically, with each style allotted the same space: one page of text and one illustration. Pillar to Post deals with exteriors, Homes Sweet Homes with interiors. Otherwise there is no attempt at fairness, which is fatal to humour. Like his friend and contemporary Kenneth Clark, Lancaster felt the Edwardians’ horrified fascination with the Victorians in general and the Gothic Revival in particular, that ‘crazy antiquarianism’ which began with Ruskin, ‘whose distinction it was to express in prose of incomparable grandeur thought of an unparalleled confusion’, after which all hell broke loose. The ‘monstrous union that begot the Albert Memorial’ later spawned the ‘olde Tudor tea shoppes and Jacobethan filling stations’ to be found all over Britain. Lancaster’s taste, however, was only partly typical of his time. He was no respecter of styles, however academically lauded, disliking the west front of Salisbury Cathedral and almost everything Egyptian, from the ‘striking and offensive motifs’ in the painting and furniture that has ‘unfortunately been preserved all too well in the tombs of the pharaohs’, to the pyramids themselves which, though individually possessed of ‘size, dignity and durability’, were nevertheless ‘a trifle monotonous’. The point is made with a drawing of a very large pyramid beside a very small palm tree and three minuscule camels. Somehow, though drawn with the barest possible outline, Lancaster manages to make the pyramid look both smug and domineering while in the distance another one, identical, heaves over the horizon.

The Romans were flashy, their true genius was as engineers. The Elizabethans made technical advances, but having only a confused and provincial view of the Renaissance, misapplied them, as illustrated by an ungainly country house, a cross between two seasoned favourites of Olden Times, Hardwick Hall and Burleigh, on which the pierced parapet spells out, instead of a heraldic motto, ‘a stitch in time saves nine’. Lancaster’s high points are the Greeks, the Gothic of Chartres, the Georgian terrace and the English Renaissance of Jones and Wren, which are admired but not venerated. Wren appears inside St Paul’s, a Baroque feature in himself with curly wig and generous embonpoint, surveying the dome through a spyglass. Arriving at the present, Lancaster watches it go past on the left, ‘Marxist non-aryan’, and on the right, ‘Third Empire’, portrayed in a pair of virtually identical examples of megalomaniac neoclassicism which leaves each ideology to satirise the other. Both in the ‘declamatory and didactic idiom’, they are distinguished chiefly by the swastika on one pediment and the hammer and sickle on the other, with the added distinction that the anti-capitalists have abolished capitals on their columns. Not only was this sort of ‘sacro egoismo’ boring, as Lancaster points out, it was unoriginal, having been done earlier and much better by Napoleon. ‘It was, indeed, unfortunate for Herr Hitler,’ he writes, ‘that the German pavilion at the Paris exhibition should have been within a hundred miles of the Arc de Triomphe.’

Lancaster’s early books were part of a flourishing interwar vein of satire which the later and much written about ‘satire boom’ of the 1960s has overshadowed. It included his exact contemporary the cartoonist Pont (Graham Laidler) and Sellar and Yeatman’s 1066 and All That, which came out in the same year as Pillar to Post. The contrasts are instructive: 1066 and All That is an in-joke, all the facts are wrong and the book is only funny if you know the right answers; Lancaster’s facts are all correct. Readers who know more about architectural history will find more nuances to enjoy, but it is not necessary to know anything. The books are as Gombrich described them, an introductory course of laconic brilliance. Homes Sweet Homes is also a study of national characteristics, mostly English and Scottish, with a sidelong look at the French. It appeared just after the outbreak of war, as the ‘oil lamps, gas mantles, electroliers, olde Tudor lanthorns, standards and wall brackets’ were going out all over Europe. Its tone is similar to Pont’s The British Character of 1936, which digs gently at bad food, smoking fires and over-ambitious landscape gardening, but Lancaster has none of Pont’s underlying cosiness. His homes offer little refuge from the darker sides of life because, as he writes in the introduction, ‘whether it be a Tudor villa on the bypass or a bomb-proof chalet at Berchtesgaden, there’s no place like home.’ As age succeeds to age one kind of inconvenience gives way to another, from smoky Norman halls to the stark artistic interiors of the ‘First Russian Ballet Period’. Meanwhile in the ‘Ordinary Cottage’ a comfortable soul, with her kettle on the hob and a reproduction of The Monarch of the Glen on the wall, sits in an armchair reading the paper. Over the fireplace is written ‘The Lord Will Provide’, the headline reads: ‘torso found in bath.’

Wherever Lancaster’s genius came from, it wasn’t his education. After St Ronan’s he continued along the conveyor belt on which his class and comfortably moneyed background had set him. From Charterhouse he went to Lincoln College, Oxford to read English, maintaining all the while a steady level of underachievement, sporting and academic. His headmaster’s final report dismissed him as ‘irretrievably gauche’ and he left university with a ‘gentleman’s fourth’, the only degree, apart from a first, that had any cachet, as it implied one had better things to do than swot. Lancaster found plenty to do in the Oxford of the Brideshead generation. As a non-hearty he was the natural prey of the rowing club but avoided having his sheets shredded when his friend Robert Byron repelled the would-be invaders, who ‘fell like nine pins before a barrage of champagne bottles flung … from a strategic position at the head of the stairs with a force and precision that radically changed the pattern of Oxford rowing for the rest of the term’. Lancaster contributed cartoons to Cherwell, but his first and most lasting cartoon was undoubtedly himself. At Oxford he created the figure he would remain, a physical and social caricature. He had a strong, well-formed, bulldog head set on an incongruously small and slender body and he now further unbalanced the effect by growing a large moustache. Although this never achieved what he thought were the ideal dimensions, which would have made it visible from behind, it was nevertheless striking, and he combined it with everything he had not been allowed to wear at school, including shirts with attached collars, loud checks and a monocle. From now on he was recognisable at a considerable distance, but at the same time invisible. ‘Osbert’, as Hugh Casson later wrote, was ‘a performance’. Few people felt they knew what lay behind it.

John Betjeman knew more than most and was probably Lancaster’s closest friend. They met at Oxford and soon realised that they shared a sense of humour and a passion for architecture which was the basis of an enduring friendship. When Betjeman became assistant editor of the Architectural Review, Lancaster, who had been making somewhat desultory efforts at a career, was at last a round peg in a round hole. He wrote for the magazine, everything from captions to art criticism and gossip, much of it illustrated. As a critic he was predictably sharp on the old warhorses of the Royal Academy: ‘Never, surely, have Mr Farquharson’s Highland sheep had to fight their way through so fierce, so snowy, a blizzard as they do in No 89. Gallery One.’ He was, less predictably, quick to spot the value of graphic art, writing admiringly of the posters commissioned by Shell and London Underground from McKnight Kauffer, John Piper and others. Piper contributed to the Review, as did Evelyn Waugh (one of the few people Lancaster positively disliked), Osbert Sitwell and Penelope Chetwode, whom Betjeman later married. With Lancaster’s first wife, the artist Karen Harris, they made a natural foursome, Karen’s family being well up to the levels of eccentricity of the rest. Her father, who was a vice-chairman of Lloyds Bank, suffered from numerous delusions, including a belief that he had crossed the Channel with Blériot, while her mother painted what Piper called ‘terrible chi-chi’ pictures under the name of Rognon de la Flèche. Both couples enjoyed the tragicomedy of English provincial life as experienced during the weekends the Lancasters spent at the Betjemans’ home in Uffington. On one occasion, at a WI meeting to award prizes for the best homemade wine, Betjeman and Karen Lancaster were joined by Maurice Bowra to sing ‘Sumer is icumen in’, accompanied by Osbert on the flute, Penelope on the zither and Lord Berners on the piano. The performance was punctuated by successive explosions, as bottles of homemade wine blew up, showering the audience in broken glass and elderberry juice while the music carried on regardless. Lancaster later said that he had never spent an evening in such ‘continuous and unalloyed pleasure’.

It was an approach to architecture and to life very different from anything Nikolaus Pevsner had experienced in Göttingen and when, having left Germany in 1933, he joined the editorial team of the Architectural Review, he was not a natural fit. A division developed between the side of the magazine which espoused the International Modern Style, in which Pevsner was supported by his fellow émigrés Lubetkin, Gropius and Mendelsohn, and the more conservative Lancaster-Betjeman axis. Lancaster had no time for what he referred to as ‘that Bauhaus balls’, while Betjeman complained that ‘the Herr Doktor Professor’ dismissed him as a lightweight ‘wax fruit merchant’. Kenneth Clark patronised Pevsner. Once, having arrived early for an appointment with Clark at the National Gallery, Pevsner got out his notebook and went on with what he was writing. When Clark appeared he remarked drily, ‘Immer fleissig, Herr Doktor, immer fleissig’ [‘Always busy, Herr Doctor, always busy’]. No English gentleman, even one who could speak a foreign language, would ever be caught actually working. Yet although much has since been made of the supposed feud between the modernists and the traditionalists, and in particular between Pevsner and Betjeman, in reality the personal tensions were much less significant than the resulting cumulative effort. Pevsner, who was neither so rigid nor so humourless as Betjeman liked to pretend, wisely took no notice of the sniping and the Review was in effect a collaboration across the whole range of opinion. Beyond the magazine the two schools of thought continued to complement one another. Pevsner and Betjeman both became mainstays of the Victorian Society, Pevsner’s rigorously comprehensive Buildings of England volumes were the counterpart to Betjeman and Piper’s idiosyncratic Shell Guides, and Lancaster’s Here, of All Places, an omnibus published in 1958 which includes Pillar to Post and Homes Sweet Homes, if read, as Boston suggests, with Pevsner’s Outline of European Architecture, will provide ‘a sound and balanced introduction to the subject’.

Drayneflete Revealed, the last of these three reissued volumes, appeared in 1949. By then it was becoming apparent that the ideology that most threatened the British landscape was neither fascist nor communist, but Corbusian. The town planners of the postwar years set about ripping the heart out of towns and cities in the name of progress and slum clearance on a scale never achieved by the Luftwaffe. What was mostly cleared was people, who were driven up into high-rise flats or down into underpasses to make way for motor traffic. In his history of the microcosmic English town of Drayneflete, Lancaster takes the reader from the earliest days when ‘sabre-toothed tigers prowled through the tropical undergrowth where now stands Marks and Spencers’ through the days of Filthfroth the Brisling, the Romans, the Middle Ages, the rise of the local noble family, the Littlehamptons, especially the second earl, ‘Sensibility Littlehampton’, who much improved the landscape, to the coming of the railways and on to the present, which sees the once picturesque Poet’s Corner built up, plastered with advertisements and swamped with heavy traffic revolving round the Odium Cinema. Unsatisfactory as much of this may be, and every scene has the same beggar in the costume of the age, the worst is yet to come. In ‘The Drayneflete of Tomorrow’ there are no human figures. The church has been preserved as a cultural monument, but the rest is a panorama of ‘Communal Housing’ on pilotis, flyovers, underpasses and road bridges. It was a vision of what later became known as Croydonisation and it was remarkably prophetic. Not until 1965 did London catch up with Drayneflete, when Leslie Martin put forward a plan for Whitehall which proposed demolishing most of it, leaving the Palace of Westminster and the Abbey marooned on lawns, surrounded by concrete ziggurat office buildings which were to be connected by vast underground tunnels. In the end it was irresolution rather than outrage that led to the scheme being dropped in 1970.

But Drayneflete isn’t a polemic. Lancaster, ever even-handed, is as much amused by his friends as his adversaries, and the whole book is a parody of the Shell Guides, beginning with the acknowledgments, which typically feature effusive thanks to at least one aristocrat, ‘whose kind interest and charming sympathy added so much to the pleasures of research’, an earnest clergyman, Canon Stavely-Locker, and the local antiquarian obsessive, in this case Miss Dracula Parsley-figett, ‘a veritable mine of extraordinary information which could have been obtained from no other source’. The text is a masterpiece in the spirit of Lancaster’s hero and fellow old Carthusian Max Beerbohm, culminating with the last of the local gentry, the poet Guillaume de Vere-Tipple, who now writes under the name of Bill Tipple. Tipple’s slim lower-case volume, the liftshaft, was published by Faber in 1937. He has been unhelpfully influenced by T.S. Eliot:

Delenda est Carthago!

(ses bains de mer, ses plages fleuries,

And Dido on her lilo à sa proie attachée)

Lancaster was famous by the time Drayneflete appeared and had been since 1939, when he invented the pocket (as distinct from the strip) cartoon for the William Hickey column in the Daily Express. He drew more than ten thousand of them over the next forty years and his characters, especially Maudie, Countess of Littlehampton, Mrs Frogmarch the Tory lady and Canon Fontwater, played out the range of topical problems from the Cold War to the extremes of 1960s fashion. ‘Tell me, dear child,’ Maudie asks her pelmet-wearing daughter at Ascot, ‘which particular horse did you put your skirt on?’ The white heat of technology fails to improve the streets of Drayneflete while the Jeremy Thorpe scandal leaves Lord Littlehampton in a fixed stare of catatonic horror. Lancaster’s other work in later life included a contribution to the Festival of Britain and a distinguished and still under-recognised career as a stage designer. He continued to write and to stand his own particular ground between extremes, making fun of hippies, who he said were more fun to draw than civil servants, and left-wing student activists, yet one of his rare overtly political cartoons was an attack on apartheid, which he loathed. He was at times criticised for prejudice and exaggeration, which is surely to miss the point of satire, but he answered by explaining that his views were ‘always those of an Anglican graduate of Oxford with a taste for architecture, turned cartoonist approaching middle age and living in Kensington’. Like the moustache and the monocle it was a disarming tactic that enabled him to hide in plain sight. What lay beyond what Casson called the ‘portcullis of anecdotes’ remains obscure and probably always will, while ‘Osbert’ the performance, entertaining, ‘meticulously practised and … at times disturbing’, endures.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.