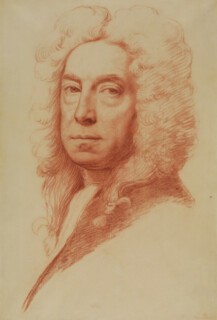

‘I wake early , think; dress me, think; walk, think; come back to my chamber, think; and as I allow no thoughts unworthy to be written, I write.’ There is a clock-like rhythm to this description of a daily routine, written by a man obsessed with time. Jonathan Richardson (1667-1745), the son of a London silk weaver, rose to prominence in the early decades of the 18th century as England’s leading art theorist and portraitist. Abandoning a career as a scrivener, he went on to paint writers (Pope, Steele, Prior), aristocrats (the Marquess of Rockingham, Lady Mary Wortley Montagu) and doctors (Richard Mead, Sir Hans Sloane). But he turned down an offer to be the King’s Painter because he objected to ‘the slavery of court dependence’. His writings on art were read widely (his Essay on the Theory of Painting, published in 1715, was on Delacroix’s reading list a century later). ‘Painting has another Advantage of Words,’ he wrote, ‘and that is, it pours Ideas into our Minds, Words only drop ’em.’ He taught Thomas Hudson, who in turn taught Joseph Wright of Derby and Joshua Reynolds. By the time of his death – suddenly, on sitting down in his chair after his usual morning walk – he owned ‘unspecified’ amounts of bank and South Sea stock, as well as five London houses.

A small selection of astonishing self-portrait drawings, on view at the Courtauld’s new Gilbert and Ildiko Butler Drawings Gallery until 20 September, shows how, after he had turned 61, Richardson compiled a visual diary, regularly scrutinising his appearance by means of mirrors and from all angles, bewigged and unwigged, frontally and in profile. As Susan Owens points out in her excellent catalogue, the drawings were done privately and autonomously, intended only for himself and close friends. They weren’t for sale, and they weren’t preparatory studies for paintings. Horace Walpole, who said that Richardson ‘drew nothing well below the head’, thought he produced a self-portrait a day; in reality it was more like every week or two. (A total of 55 are known today; 16 are exhibited here, as well as four more depicting his son.) It isn’t clear whether he always envisioned them as a sequence as such, but making them became habitual, along with writing poems. Most of them are dated with a precision more common in the 19th century: Constable’s cloud studies, Monet’s haystacks.

Richardson’s self-portraits show a man coming to terms with ageing. One of his poems, ‘My Own Old Age’, speaks of the disjunction between the way he feels and the way he looks, and of the jolt he gets from seeing the hunched shoulders and aged face of a contemporary: ‘Open my partial eyes to see,’ he wrote, ‘That thus, alas! it is with me.’ In the drawings he tried to enact the moment of seeing his face anew over and again; to create a sense of estrangement from himself, to view his most subjective attribute as objectively as possible. Among the earliest in the series are two in black and white chalk on rough blue paper – the cheapest available, used for wrapping goods like sugar, but favoured by artists for its readymade mid-tone (as well as for its art historical connection to the Venetian old masters). They are dated 4 May and 24 June 1728; in the first, Richardson, with his slouchy indoors cap, left eyebrow slightly raised and lips just parting, turns to his left; in the other, turning to his right, his eyes face out at us (or rather at himself), with lips pursed, brow furrowed. On its verso, Richardson’s son – described by his father as ‘my other self’ – has added a line from Horace indicating that the self we see here is one ‘in secret from the mob and public eye’. The interval between the two moments recorded in these drawings is significant. We are asked to consider what has changed, to think of the face in movement. On 5 December 1730, Richardson tried to capture his eyes in the act of blinking; on 21 November 1735 he seems almost to recoil from himself, eyes wide with a nervousness matched by his quivering line.

Instantaneity is a rare quality in portraits of this period. Richardson wrote of the kind of oil portrait he was used to producing for his fashionable patrons that it should be ‘a sort of General History of the Life of the Person it represents’. ‘Upon the sight of a Portrait,’ he explained, ‘the Character, and Master-strokes of the History of the Person it represents, are apt to flow in upon the Mind, and to be the Subject of Conversation: So that to sit for one’s Picture, is to have an Abstract of one’s Life written, and published.’ But the private drawings form an inventory of what he called ‘all my swift successive nows’. Together they amount to an exploded diagram of the single, ideal oil portrait that synthesises the sitter’s past and present into one ‘General History’.

The drawings allowed Richardson to position himself both in and out of time. (He considered time as much an artist’s material as canvas and oil.) He sometimes went back to earlier painted self-portraits and translated them in graphite, returning younger selves to his present; he drew himself as if memorialised in ancient cameos or coins; and he often layered his drawing style with references to the self-portraits of past artists: Rembrandt, Bernini, Palma il Giovane. (Richardson’s enormous collection of Continental drawings was one of the finest in Britain; it took 18 nights to sell 983 of them at auction in 1747.) Perhaps it was his career as a portraitist that gave him his special feeling for time. The portrait’s function, after all, was to populate the here and now with faces from the past, when ‘the Originals … are out of our reach, as being gone down with the Stream of Time, or in distant Places,’ as he put it. ‘In Picture we never dye, never decay, or grow older.’ Not only that, but artistic labour was a way to halt the march of the hours: ‘Who labours lives, commands ev’n life to wait,/And seems, with innocence, to combat fate,/With glory to reverse the rigid law,/Not to be drawn by time, but time to draw.’

Richardson’s poems and his project of graphic self-serialisation hover between the moralising memento mori and a more modern sense of resignation. He considered it a duty, in the name of virtue and of God, to make the most of his allotted time. By writing in the mornings when everyone else was asleep, he had ‘out of what most people squander away as offals of time, formed a kind of additional life’. Yet – especially in the drawings – he was a dispassionate observer of the passing seconds. ‘My life, each morning when I dress/Is four and twenty hours less,’ he wrote. Another poem exhorts a clock to stop ticking. Perhaps he was afraid of growing old, but he could also say of the ageing face that it was a ‘Beauty superior!’ whose ‘deep furrows’ were ‘scars receiv’d in honourable war’. He could lament that ‘Life now is so much shorter than it was,’ but one of his favourite phrases is reported to have been ‘as fast as possible’.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.