Riccardo Selvatico , the progressive mayor of Venice in the early 1890s and author of poems and comic plays, lost his post to a less secular, less intellectually minded candidate before the inauguration of his great scheme for the city, the Biennale, in 1895. Selvatico must have known his time was short: construction began in May 1894, only a month after the idea was announced at a meeting of artists and writers at Caffé Florian, starting with the demolition of the Tommaso Meduna riding school, which housed army horses and an elephant called Toni. The proposed site, the Giardini on the south-east shore of the city, was a Napoleonic initiative to provide for ‘our good city of Venice … a public promenade … with avenues and a garden’. The Palazzo Centrale, which is still the heart of the Biennale, was the only exhibition space in the early years, but visitor numbers were high from the start: 200,000 in 1895, 250,000 in 1897, 300,000 in 1899 (around the number that visit today).

Lack of space and a desire to make the exhibition truly ‘international’ – as well as to raise revenue – led to the suggestion of adding special pavilions for artists from abroad. The city would fund the construction of the new buildings, with the expectation that the beneficiary country would buy the pavilion on completion. The first to do so was Belgium, in 1907, followed by Hungary, Britain and Bavaria (now the German pavilion) in 1909, and the French and Swedish pavilions in 1912 (the latter was given to the Netherlands when the Swedes failed to pay). After the First World War came Spain, Czechoslovakia, the US, Greece and Austria and the site was expanded across the canal to incorporate the gardens of Sant’Elena. Following a hiatus from 1943 to 1947 (Mussolini’s 1942 Biennale, dedicated to military art but not mentioning the war, didn’t see many international contributions), the increasingly full Giardini gave space to Switzerland, Israel, Venezuela, Japan, Finland and Canada. Shaped roughly like a triangle, with two main boulevards leading away from the entrance to the Palazzo Centrale in the north and the British pavilion in the east, the Giardini now house 29 national pavilions and a much enlarged Palazzo Centrale. With its wide avenues, lined by tall trees (chosen by Napoleon’s botanist to withstand the lagoon climate) and flanked by pavilions of 19th-century, modernist and modern design, it reminds one of nothing so much as London Zoo.

The Palazzo Centrale has lost its original façade; eight pairs of raised Ionic columns and a bas relief of the Triumph of Pallas, topped with a statue of Glory, have been stripped down into a white square with four minimalist columns. This year it’s hung with heavy black shrouds drenched in oil by Oscar Murillo, fascistic and funereal, and in place of Pallas’ pediment is a neon by the American artist Glenn Ligon, faint in the bright sunshine, which reads ‘blues blood bruise’ – a quotation from Daniel Hamm, one of the Harlem Six. Each Biennale has a new artistic director; this time it’s Okwui Enwezor, Nigerian by birth (the first from Africa), now living between Munich and New York and previously artistic director of documenta, the Biennale’s more trendy, conceptual cousin in Kassel. Enwezor’s Biennale is called All the World’s Futures and there’s little optimistic or utopian about it. He believes we are living in dark times. ‘The global landscape,’ he writes in his introduction to the catalogue, ‘lies shattered and in disarray, scarred by violent turmoil, panicked by spectres of economic crisis and viral pandemonium, secessionist politics and a humanitarian catastrophe on the high seas, deserts and borderlands, as immigrants, refugees and desperate peoples seek refuge in seemingly calmer and prosperous lands.’

Countries manage their pavilions in different ways, though usually their ministry of culture appoints a commissioner, who chooses a curator, who chooses the artists and arranges the layout. The Biennale’s artistic director curates the two main spaces, the Palazzo Centrale and the Arsenale, which lies to the north of the Giardini. The many countries that aren’t represented in the Giardini can rent space elsewhere, either in the Arsenale or, increasingly, across the city. National pavilions are a status symbol, of course (Azerbaijan has two), but beyond that? They might honour an individual artist (the approach of the British Council) or act as a showcase for the country’s current trends, a publicity stunt, a forum for self-criticism, a curatorial opportunity. This year’s Kenyan exhibit was withdrawn after widespread criticism that its Italian curators had chosen more Chinese artists than Kenyan ones.

The 32 rooms of Enwezor’s Palazzo Centrale are centred on Das Kapital (‘Capital is the great drama of our age’), with the main arena playing host to a reading of the entire work. Marx is artist #047 in the catalogue. The performance, organised by the installation artist Isaac Julien, is preceded by a video interview with David Harvey for those who missed ‘Reading Marx’s Capital with David Harvey’ on his website. It’s a world away from the sunshine of the gardens and spritzs on the terrace (the product of another empire that claimed the city) – just as Enwezor intended – but doesn’t quite work, like Christoph Büchel’s attempt to turn a disused church into a mosque for the Biennale: it was shut down by city authorities for having more to do with religion than art. Also in the Palazzo Centrale are Marlene Dumas’s skull paintings (not included in the recent Tate Modern retrospective), Jeremy Deller’s 19th-century broadsides and Walker Evans’s Depression-era photographs. Alexander Kluge’s installation for three projectors addresses Marx – and Eisenstein – head on, in a series of interviews and short clips with titles like ‘Lament of the Unwanted Product’, ‘Machines Abandoned by People’, ‘The Magic of Antiquity’, ‘Becoming Liquid’ and ‘I’ve never seen two dogs exchange a bone’.

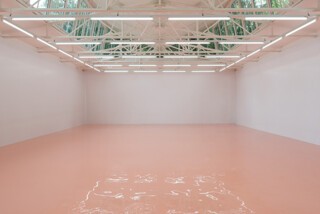

This Biennale takes itself seriously. The accompanying pamphlets are more likely to provide the political or historical context to a short documentary than try to explain a conceptual creation (though there still are some of those). The simply beautiful seem one-dimensional by comparison. The Japanese pavilion, an Instagram hit, is a maze of fine red wool, the skein twisted and knotted with impossible complexity and hung with thousands of keys like bats in a crimson cave. The Swiss have opted for a pale pink pool of water. The Nordic (i.e. Scandinavian) and Finnish pavilions seem to have commissioned to type: the Finns’ is a dark room of charcoal, tar and jute inspired by primeval forests while Camille Norment’s Rapture, in one of the Giardini’s most beautiful pavilions (designed by Sverre Fehn in 1962), is a hall of light and broken glass, where ethereal sounds are relayed by long angular speakers. The French have dug up three Scots pines and set them on slowly rotating platforms, one in the pavilion, two outside; they make an almost imperceptible waltz against the Giardini’s formal layout.

It’s hard not to be depressed by the British pavilion. Positioned at the summit of the Viale dei Platani it probably has the finest setting after the Palazzo Centrale. The building was designed by Edwin Alfred Rickards in 1908, a conversion of a former café into an Italianate British country house. The main façade is an open raised loggia, surmounted by four slender columns with a central flight of steps, which nods through its Georgian influence to the Venetian Andrea Palladio. It’s one of the few pavilions to have remained unchanged. The only advantage given to it by Sarah Lucas, so insightful in interview, so frustrating in practice, is the marigold yellow interiors (she calls them ‘deep cream’) which set off the pale terracotta façade nicely. Inside the plaster casts of her female friends’ lower halves – some sitting cross-legged, other on their knees or standing jauntily – aren’t improved by the insertion of cigarettes into orifices, though as she says, YBA style, in the accompanying text, ‘if you happen to be one of those people who feel the sculptures would have been better without the cigarettes, well, I put them there for you too.’

More intriguing are the Venezuelan pavilion, with its breastfeeding masked guerrillas, and Joan Jonas’s dreamy videos of children performing strange rituals inspired by Nova Scotian ghost stories for the American pavilion, one of the largest (and most boring) national buildings. Some countries have responded to the pavilion itself: Russia’s Irina Nakhova, a founder of Moscow Conceptualism, has restored the 1914 building to its original green. The Austrian pavilion looks empty; Heimo Zobernig’s contribution is a black false ceiling. It doesn’t have much to say, unlike the Uruguayan pavilion by Marco Maggi, which also gives the impression of having nothing in it until one gets up close. The white walls are covered with thousands of tiny paper cut-outs, connecting and intersecting like circuit boards or the map of a futuristic city. Greece and Canada have both made their pavilions into shops: the Greek a re-creation of a closed-down leather store, a casualty of economic forces; the Canadian a more fanciful affair that delights in accumulation for its own sake. If you climb to the top you can put a euro in a slide that eventually drops into a glass panel, like the slot games in seaside arcades.

An interesting accident of this Biennale is the tension between the desire to document (which many critics have seen as earnest and un-artistic) and the imperialism of the collector, who assigns meaning. Australia’s Fiona Hall has more than a thousand works in her cabinet of curiosities: pieces of driftwood, birds’ nests made out of dollar bills, bread sculptures, cuckoo clocks, animal figures created by indigenous women. The Dutch pavilion by Herman de Vries arranges the natural world in sensory forms. The centrepiece is a two-metre-wide circle of rose petals on the floor; you can smell them from the avenue beyond. On the walls are tableaux of 84 samples of earth from different parts of the world – an abstract pattern of yellows, pale greys, orange-reds, burnt and dusky browns – and From the Laguna, a visual diary of Vries’s residency in Venice. The 123 A4 frames contain leaves (arranged by type and size), sand, soil (again), photographs, snail shells and shards of blue glass, carefully ordered and presented like displays in a museum of natural history. They aren’t as far from the Canadian pavilion’s jumble of odds and ends as they might seem to be. Both are evidence of the tangible pleasure of collecting and arranging: the art of the curator. Here though it’s the artist as curator of natural or human environments; he doesn’t interfere with the substance but simply frames it.

It’s close to the originating spirit of the Biennale. No matter how far Enwezor tries to pull it into darkness the leisurely arrangement of the Giardini, with their showrooms of national treasures, retains the grand exhibitionary spirit of the 19th century. The logistics of the Biennale are always its greatest achievement: 89 nations, hundreds of venues, a film programme, plenary sessions, performance schedule, special projects, collateral events. Enwezor’s Biennale is more interesting for what you learn than what you see; as Peter Campbell wrote of Sarah Sze, another artist of arrangement (and also at the Biennale), you don’t so much look at what’s in front of you as read it.

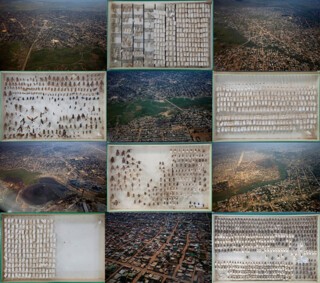

There are attempts to question underlying attitudes. The artists of the Polish pavilion, Joanna Malinowska and C.T. Jasper, ask whether 19th-century artistic forms still have the power to represent national identity and answer with a video of their trip to Haiti to stage Stanisław Moniuszko’s 1847 opera Halka (a story of class-divided love) for a bored-looking assembly of Haitians descended from Polish soldiers. The soldiers had been sent there by Napoleon to quash a slave rebellion but instead decided to join it. It doesn’t seem like the right way to go about answering their question. The Belgian pavilion, built during the reign of Leopold II, hosts European and Africans artists concerned with ‘colonial modernity’. Sammy Baloji contrasts display cases of malarial mosquitoes with photographs of the undeveloped zone between Lubumbashi’s white and black neighbourhoods, kept empty to ensure the white neighbourhoods are out of the mosquitoes’ range. In the Palazzo Centrale is an oddity, ‘Jardin d’Hiver’ (1974), a 19th-century set-piece from Marcel Broodthaers’s Décors series, a collection of potted palm trees, display cases and vitrines, as well as folding chairs from a colonial verandah. The participants have disappeared, but perhaps they’ve only wandered into a neighbouring pavilion.

The Arsenale, a complex of former shipyards and armouries dating back to the 12th century, was first used for the 1980 Biennale. The main building, the long L-shaped corderie, was built in 1303 (the current building dates from 1585) for making hawsers and naval ropes. At its peak in the 16th century, when Galileo was a consultant to its engineers, the Arsenale employed thousands of men to build merchant and naval ships: they could produce a ship a day. Now the sheds are empty, the grand hydraulic crane (British, 19th-century, the last of its kind) a relic of the site’s last era of importance, as the main naval base in a newly unified Italy. The trek down the 316m corderie is unrelenting at the best of times – room after enclosed room – and Enwezor seems determined to obliterate the ease of the Giardini. It opens with Bruce Nauman’s flashing neons – ‘life, death, love, hate, pleasure, pain’, ‘eat/death’ – and a series of angry sculptures: Adel Abdessemed’s knife bouquets, Melvin Edwards’s twisted scrap-metal assemblages, Monica Bonvicini’s black concrete chainsaws, Pino Pascali’s replica cannon. The Gulf Labor Artist Coalition has a banner asking: ‘Who is Building the Guggenheim Abu Dhabi?’ Two separate video installations, which use montage footage of different forms of labour (one mostly European, the other African), gesture to Marx. Better are the Chilean and Irish pavilions: the former includes the photographer Paz Errázuriz’s portraits of Santiago transvestites under Pinochet; the latter, by Sean Lynch, connects the flow of capital to Venice’s water-bound wealth through a series of stone sculptures and a video installation. Art as artefact, artist as historian, storyteller, ethnographer. Georg Baselitz’s monumental naked self-portraits, hung upside down in a central octagonal gallery, seem, in contrast to the density of research projects and narratorial installations, silent and exposed – not in their subject matter so much as the display of art qua art.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.