At La Mécanique des dessous (‘The Mechanics of Undergarments: An Indiscreet History of the Silhouette’), an unexpected exhibition about underwear in Paris two years ago (Jenny Diski wrote about it in the LRB of 10 October 2013), there was a room where you could try on bustles and lobster tails and panniers and waist cinchers and other cunning elements of the dressmaker’s art made to press the body into different shapes. It turned out that the look these undergarments achieved was not the prime effect – especially as there were no overgarments to complete it. Chokers, heels, tight-lacing, hip-widening, bum-lifting straps change the feel of being inside your own body: you have to hold yourself differently, walk differently – and breathe differently. ‘Deportment’ used to be a key term in the civilising process: finishing schools taught young ladies to walk with a book balanced on their head. Keep that head up and tuck that tail in!

The word ‘deportment’ seems to have vanished along with aspidistras and parlours, but the concept hasn’t: Alexander McQueen’s designs, spectacularly displayed at the V&A in Savage Beauty (until 2 August), changed the way you walked, and not just because you were raised up on jewelled chopines like a Venetian courtesan in a period of acqua alta, or forced to balance like a tightrope walker on feet encased in hulking armadillo shoes, which did for his runway models what pointe shoes did for ballerinas after Marie Taglioni first stuffed her ballet slippers. But while Taglioni became an ethereal fairy, the armadillo shoes and fabric sheaths printed with snakeskins of the last, astonishing McQueen collection, ‘Plato’s Atlantis’ (2010), turned their wearers into aliens, creatures of the deep and outer space, something computer-generated from the film Avatar.

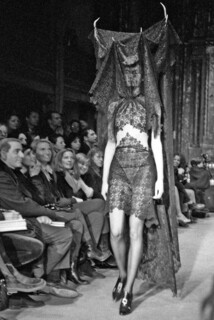

The writers and interviewees in the fine catalogue of the show, edited by Claire Wilcox, include many collaborators and models as well as art critics, and they testify to the excitement of being made to improvise a different gait and posture, of being restructured, altered in scale and in relation to the space their bodies occupied.* They defend McQueen against charges of cruelty, misogyny and racism: the black model Debra Shaw appeared manacled and hobbled, the dancer Shalom Harlow was pelted by paint-spraying robots, models paraded on a constantly tilting floor in a re-enactment of a dance marathon, as in They Shoot Horses, Don’t They? Their descriptions evoke the way a call girl may speak about her sense of being in control; they also fit with an argument about S&M that is gaining ground: that master/slave roles can be empowering for women. I am deeply sceptical about these arguments about sex and pain, but the theme is certainly present in McQueen’s work, from the notorious ‘Jack the Ripper’ student show to ‘It’s Only a Game’ (2005) to the bondage allusions (horses’ bits, braces, straps, harnesses, hoods, masks and piercings). McQueen himself made a series of comments about women which have the candour that won him many friends and admirers: ‘I think there has to be an underlying sexuality. There has to be a perverseness to the clothes. There is a hidden agenda to the fragility of romance … I’m not big on women looking naive.’ We need you, Angela Carter! We need your help!

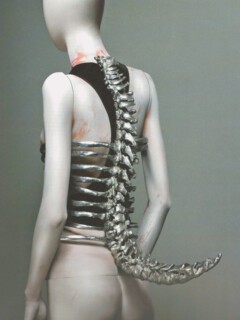

Carter thoroughly upset the bien pensants with her essay The Sadeian Woman (1978) where she argued that Sade ‘was unusual in his period for claiming rights of free sexuality for women and in installing women as beings of power in his imaginary worlds … I would like to think that he put pornography in the service of women, or, perhaps, allowed it to be invaded by an ideology not inimical to women.’ She also makes the connection between Sade’s misanthropy, as she calls it, and his splitting of women’s bodies from ‘the mothering function’. McQueen seems to me to fascinate for similar reasons. Some of the pull he exerts on huge numbers of people arises from this side of his sensibility: there’s no hint of motherhood; he disliked the way that traditional décolletage revealed the breasts, and instead encased the whole female torso in coiled silver, mussel shells or razor clams – even glass.

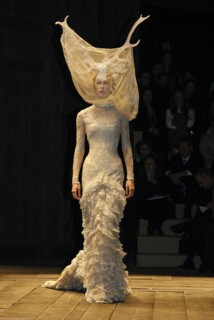

It’s perplexing that, historically, the clothes of working people are loose and comparatively comfortable, though made of rough materials, whereas elites have forced themselves into carapaces. Enveloped in vast billows of clothing, crushed under crowns and huge headdresses, so weighted down with insignia that they cannot turn their heads or lift their arms, or crippled on bound feet, men and women of high status all over the world look out from magnificent portraits, defying all encumbrances. David Cannadine’s study Ornamentalism wittily captures the ways the governors and viceroys of the British Empire vied with Indian rajahs and African kings in their spectacular apparel, all of them arrayed in plumes, festoons and baubles. Something about European culture in particular seems also to associate authority with constricting dress; radicals and reformers, French revolutionaries and feminists have all called at various times for loosening those stays, unbuttoning that collar, undoing that tie.

Joan of Arc was the subject of McQueen’s 1998 autumn/winter collection, and there is a poignant photograph in the catalogue of McQueen in full armour, dreaming of chivalry. Much young adult fantasy fiction, in which Joan often figures, also stages a stand against the maternal body. By coincidence, the most recent Hunger Games movie shows Katniss Everdeen being fitted by a couturière for her role as the symbol of the Resistance, the Mockingjay. ‘We will make you the best-dressed rebel in history,’ the designer promises, as she sheathes Katniss in a McQueen-like body-hugging cuirass. When the Mockingjay is given her customised bow and arrows – powerful enough to bring down bombers – she’s told: ‘I couldn’t just make you a fashion accessory.’ A corresponding strain in Savage Beauty is directed against mere fashionable frippery, an underlying message that McQueen wanted his work to have a deeper meaning than luxury and display. ‘I don’t want to do a cocktail party,’ he said. ‘I’d rather people left my shows and vomited.’

Andrew Bolton, the English curator and director of the Costume Institute at the Metropolitan Museum, first staged Savage Beauty in New York in 2011 (where it became one of the most successful exhibitions ever – 661,509 people went to see it, exceeding all forecasts); he praises the designer lavishly, for ‘his sweeping, unbridled imagination’, his ‘raw, emotional intensity and sublime, transcendent beauty’ and approvingly quotes Judith Thurman’s claim that McQueen’s fashions were a kind of ‘confessional poetry’. Bolton continues: ‘He was a designer of unrivalled courage who seemed to find creative freedom through his torments. What you saw in his work was the man himself.’

Savage Beauty is shadowed by the story of McQueen’s life, his troubled psyche, and eventual suicide. McQueen once called himself ‘a romantic schizophrenic’ and Bolton takes Romanticism as his organising principle: each section offers a variation – Romantic Primitivism, Nationalism, Tribalism, Exoticism, Naturalism – and wraps the visitor in a total scenario: gorgeous tarnished and gold-framed Venetian mirrors in one room, a dim mortuary cave entirely lined with bones in another, and throughout a shimmering and ravishing soundscape of layered sampling and electronics created by John Gosling (aka Mekon). Bolton avoids the term ‘gothic’, but it haunts the show.

Alexander McQueen has entered that part of the afterlife where Marilyn and Amy Winehouse, Janis Joplin, Kurt Cobain and Peaches Geldof are gathered: beautiful, doomed, striving, Dionysiac youth (though McQueen was a plain-looking London boy, he was dusted in the eyes of his audience with the glitter of his creations and he liked to pose for the camera in different guises, one very alarming image showing him with a skull mask covering his lower face).

His clothes stir uneasy and morbid sensations. McQueen explored the underworlds of dress and bodies and revels in what can be done with them, to every part of them. If you imagine one of those manuscript illuminations called a Man of Wounds, which showed surgeons how to handle an injury in every part of the body, then McQueen has similarly roved over his subjects and turned his attention to every joint and limb and organ. He extended the neck with metal hoops and Napoleonic high collars, he exposed the collar bones in a chalice of roses, he carved tall elm wood prostheses like medieval caskets for the paralympic champion Aimee Mullins and, most famously, scooped the back of a dress or a pair of trousers to disclose the soft involution of the buttocks and what he saw as nature’s own line of beauty, the curve of the spine on the lower torso. The only body part he may have neglected, as far as I can see, is the armpit. In his fluid sketches, the silhouette from the side was his favourite view.

The sculptor Louise Bourgeois once said: ‘When I want to repair something I stitch it. When I want to destroy it, I cut it.’ The lumpy stuffed mannikins that she made reveal how eloquent these processes are: the slashes are violent, the suturing a gesture against further damage. McQueen himself was preoccupied with insides and injuries: anatomical figures made of wax inspired him, and the array of artefacts in the exhibition’s cabinet of curiosities includes jewellery in the form of vertebrae. The gleaming alcoves, floor to ceiling, are filled with the body armour and other pieces, many of them close to implements of torture, that the goldsmith Shaun Leane made to McQueen’s designs. The overall effect recalls a cathedral treasury in Spain, filled with reliquaries, gems, gold, disquieting and dazzling things.

McQueen showed a very early gift for making clothes – as well as a taste for bodily discipline (he enjoyed synchronised swimming with his sisters). He was apprenticed in his teens to a tailor on Savile Row and learned to cut patterns for the high end of the gentleman’s market; his spontaneous dash with the scissors astonished – and alarmed – the team at Givenchy in Paris when he arrived there, and his tailoring skills mark the wonderfully elegant suits and outfits on show in the first rooms of the exhibition. After Savile Row, he went to work for theatrical costumiers, and continued to take off into different eras and places, reprising Jacobite jabots, tartans and sashes (in the collections ‘Highland Rape’ and ‘The Widows of Culloden’), Noh theatre, Swan Lake, L’Atalante, as well as the opulent empire style of Napoleon and Josephine. At his best (and happiest?), dreamier, softer outfits, like the organza dress printed with the Portinari altarpiece, or his fabulous kimonos and ballet costumes, re-create the sensuous mood of the dressing-up trunk, and of little girls playing at wearing their mother’s party clothes.

In 1990 St Martin’s School of Art accepted McQueen, then unemployed, though he hadn’t done any of the right exams, because Bobby Hillson, the MA fashion course director, recognised his gifts; McQueen’s aunt paid the fees (he paid them back six years later when he was appointed head designer at Givenchy). Isabella Blow, then working for Vogue, was enthralled by that notorious degree show, ‘Jack the Ripper Stalks His Victims’ (1992), bought everything she could, and began to mould him for the world of high fashion. The training he received at the time no longer exists, Louise Rytter tells us in the catalogue, and a fee of £9000 pa – or more – might be hard for McQueen’s aunt to meet.

London in the 1980s and early 1990s was the proving ground of the generation who became the YBAs (Damien Hirst won the Turner Prize in 1995, and Sensation, the show that defined them, opened at the Royal Academy two years later), and McQueen’s sensibility is very close to theirs. ‘There was so much repression in London fashion,’ he once remarked, ‘it had to be livened up.’ He produced shows that reverberated with the beautiful and damned themes of the YBAs, and he shared many compass points – martyrdom, decay, hell, wild animals – with them. A group photograph taken in 2000 by Annie Leibovitz shows McQueen in a lighter mood, playing with his dogs while his studio team and friends look on; Isabella Blow and the Chapman Brothers are there, and Sam Taylor-Wood (as was), as well as the jeweller Shaun Leane, and Sarah Burton, who would take over the label after his death and made Kate Middleton’s wedding dress. All McQueen’s earliest associates seemed to have stayed with him the whole way: this was a family business built around a visionary boss.

When I was at the V&A, there were no fashionistas in evidence – most of us were rather middle-aged or even old, and stoutly dressed against a cold spring. In the last room, where the aquatic fantasies of ‘Plato’s Atlantis’ were swirling on the walls and Raquel Zimmermann was writhing with serpents as if in an initiation ceremony in New Mexico, I noticed the woman next to me run her fingers down the smooth white laminated wall, clearly to sample its texture and identify what it was made of. She made me realise that nothing in the show can be touched, a kind of erotic prohibition that matches McQueen’s dominant note. But there was something so knowledgeable in the way she was testing the material, I guessed she must be in the rag trade, and that many of the visitors that day were people who worked in the trades McQueen had called on: corsetières, cobblers, armourers, milliners and taxidermists; weavers of lace, braid and ribbons, makers of buttons and tassels, of carnival masks and gloves; plumassiers, who can do anything with feathers; bead embroiderers, upholsterers, leather workers (saddlers), as well as surgical limb designers and makers of medical braces.

‘Demolish the rules, but keep the tradition’ was another of McQueen’s maxims. Customising was a watchword of punk, with Malcolm McLaren and Vivienne Westwood the subject of a more recent show at the Met also created by Andrew Bolton. Customising is a form of bespoke and bespoke relies on those trades that go back to the Middle Ages and are commemorated in the names of the City Companies and Guilds (cordwainers; haberdashers, cutlers, goldsmiths). McQueen was a Londoner, and he had what Christopher Breward calls ‘the assertive pub-and-gutter glamour of London’s seamier side’ as well as the nous – his was a different kind of knowledge from his taxi driver father’s, but it was similarly rooted in the city streets. His couture thrived on old fabricating skills in the period of their decline – Soho and Brick Lane used to be full of shops and wholesalers dealing in haberdashery, in fancy stuff, buttons and bows. For his degree show, he went round begging the ends of rolls from such places. I think there is one shop of that sort left in Soho, a place of fabulous colour and skill and fantasy: the Cloth Shop in Berwick Street. Brick Lane windows are still bright with fabrics.

Haute couture has always been intertwined with exquisite stitching and other handiwork, and the new promotion of fashion as a fine art has been given ballast by the Metropolitan Museum’s Costume Institute. The ambition to be an artist, which is so evident in McQueen’s runway shows and strongly brought out by the performance-cum-installation of the luxurious mise-en-scène at the V&A, has also found support in the rise of the handmade as a value for artists – though the latter are sensitive about the label ‘craftsman’. Ruskinian theories are returning, and William Morris has been adopted as a hero by Jeremy Deller, who juxtaposed him admiringly with Andy Warhol in Love Is Enough, the show he curated recently at Modern Art Oxford. Couture perfectionism and beauty, especially when defaced and slashed and paint-splattered and generally savaged in one of McQueen’s fits of potlatch craziness, belongs in this part of the aesthetic spectrum, which is now acquiring higher status, alongside Grayson Perry’s pots and tapestries, Rachel Kneebone’s ceramic figures, or Polly Morgan’s taxidermy sculptures.

Isabella Blow and McQueen didn’t remain as close, but her death marked a change: after the 2008 collection ‘La Dame bleue’, a memorial to her wit, extravagance and hedonism, there’s a shift in the designer’s themes, from the injuries of history to anxiety about damage to nature and ecological catastrophe. Before, McQueen had found his inspiration in rage about Culloden and the Salem witch trials (his mother traced her descent to Elizabeth How, hanged there in 1692): he now turned to the environment, and the mood grew darker – crushed Coca-Cola cans and dustbin lids for headdresses, clothes made from bin liners and plastic bags, models parading amid trash heaps. When the photographer Nick Waplington was invited to chronicle the inner workings of the designer’s studio McQueen told him he’d chosen him for his ‘dirty messy’ style; Waplington’s book juxtaposes landscape shots of waste tips, recycling mountains and rubbish dumps from all over the world with McQueen’s collection ‘The Horn of Plenty’, a super chic retro homage-to-cum-satire-of the New Look and the elegance of Irving Penn.† It’s perhaps too easy to read this show with hindsight and find self-hatred seeping through it all, but self-disgust and the fear of imaginative collapse are forcefully conveyed. He rallied strongly with the digital innovations of ‘Plato’s Atlantis’, but McQueen was already threatening to stage his own death on the runway.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.