‘The women surrealists were considered secondary to the male,’ Leonora Carrington reported; their role was to inspire, as well as cook and clean. But she was never comfortable with being a muse, or as Breton cast her, the femme enfant whose naive access to the unconscious made her the ideal conduit for the male artist. Only women, he thought, had ‘the illuminism of lucid madness’ and ‘the sublime power of solitary conception’, and he credited Carrington with both. In photographs from the late 1930s she looks confident, daring; sure enough of herself to resist such a subservient position, though her own art kept her at the margins, and her life has often overshadowed the work. Of her writings, only a novel, The Hearing Trumpet, is still in print and nearly all her artworks are in private collections.

The curators of her first major solo exhibition in Britain (at Tate Liverpool until 31 May) would rather focus on her diverse practice than her biography, but it’s impossible to make sense of her art without it. The only daughter of a wealthy Lancashire family, Carrington was repeatedly expelled from the Catholic boarding schools her tycoon father sent her to (the nuns were disconcerted by her ambidextrous mirror-writing and attempts at levitation), though she stayed long enough at Miss Penrose’s in Florence to develop a love for Quattrocento painting. She disdained the rituals of coming out, notoriously reading Eyeless in Gaza in the royal enclosure at Ascot, and later satirised her debutante ball in a short story: the heroine sends a hyena in her place, disguised – what a mask! – by the mangled face of her maid ‘nibbled very neatly all around’.

In opposition to her parents, who thought that if you were an artist you had to be poor or homosexual, ‘more or less the same sort of crime’, Carrington moved to London to study at Chelsea School of Art, then at Amédée Ozenfant’s academy in Kensington. In 1936 the First International Surrealist Exhibition opened at New Burlington Galleries and the following year she met Max Ernst at a party organised by a fellow Ozenfant student, Ursula Goldfinger, and her architect husband, Erno. Ernst ‘opened up all sorts of worlds’ and Carrington soon went to live with him in Paris, though she later put it: ‘I ran away to Paris. Not with Max. Alone.’

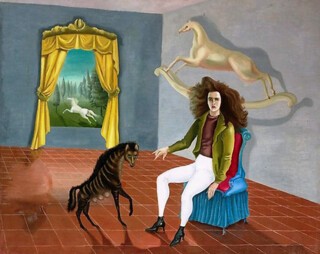

In Paris she completed her first major self-portrait, Inn of the Dawn Horse (1937). A wild-haired Leonora dressed in riding clothes sits in a room with her hyena familiar; behind her on the wall hangs a rocking horse, and through the window a second horse gallops. The painting features many of the themes she would return to in later works: anthropomorphism, wild-haired women, ambiguous interior spaces, the horse as freedom and sexuality. ‘A horse gets mixed up with one’s body,’ she said, ‘it gives energy and power.’

In 1938 Carrington and Ernst moved to a farmhouse in Provence, decorating it with bird and horse talismans to keep away disapproving parents and warring surrealists, as well as Ernst’s wife. But Max briefly returned to Marie-Berthe, and Carrington was left stranded, playing the role of ‘l’Anglaise’ at the local café like a ‘performing animal’. The triangle provided material for her story ‘Little Francis’, with Ernst as the urbane but ineffectual Uncle Ubriaco, torn between his demanding daughter Amelia (Marie-Berthe) and his nephew Francis (Leonora). Abandoned and distressed, Francis develops an equine head, which pays his bills but isolates him from other people. The story drifts between satire and obscure symbolism: bats sing Bach, a girl reads an obscene poem while the audience pinch her legs, Francis murders a caged monkey and meets the Great Architect Egres Lepereff (based on Serge Chermayeff), who is dressed as a Cossack and reads the Spew Matesman.

Shortly after Ernst returned to her, war broke out and he was interned first by the French as an enemy alien, and then by the Germans as a ‘degenerate artist’. Carrington was taken to Madrid by friends, where she began to suffer delusions – she had been starving herself for weeks – and was put into an asylum. Here her story becomes increasingly strange. She was given the drug Cardiazol, which induced terrible fits, before being rescued, possibly by her nanny, possibly in a submarine (her father was friends with Churchill). Chaperoned to Lisbon to board a boat for South Africa, she escaped through a bathroom window and went to the Mexican embassy, where Renato Leduc, a poet and diplomat she knew through Picasso, offered to marry her so she could get to America.

In New York life as it had been in Paris resumed, at least for a while. Most of her compatriots had fled there: Ernst, now with Peggy Guggenheim, Breton, Ozenfant, Duchamp, Mondrian. Guggenheim included Carrington in her Exhibition by 31 Women and her stories were published in American journals and surrealist magazines. Breton encouraged her to record her experience of madness; Down Below came out in 1944. Buñuel remembered her eccentric behaviour: getting up from a conversation she took a shower fully dressed, then returned dripping wet to continue it. In Paris she had infamously worn a sheet to a party and dropped it halfway through; now she was making omelettes with her guests’ hair and spreading mustard on her feet.

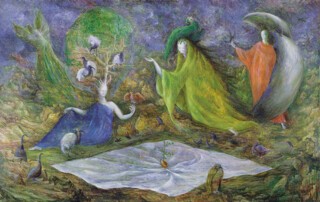

She moved to Mexico in 1943, finding a second community of émigré artists – her friendship with Remedios Varo and Kati Horna was the subject of a recent exhibition at Pallant House Gallery (Frida Kahlo called them ‘those European bitches’) – and after divorcing Leduc she married the Hungarian photographer Imre Weisz. Carrington’s better paintings are from her first decade in Mexico. The Temptation of St Anthony (1947) was painted for the Bel Ami art competition (which Ernst won); the composition – a sitting hermit and pig in front of a stream – was lifted straight from Bosch, whom she’d seen in the Prado. But Carrington’s saint has three heads (when asked why, she replied ‘Why not?’) and instead of devils he’s surrounded by female figures, one brewing a potion in her cauldron, others holding up their queen’s gigantic skirt.

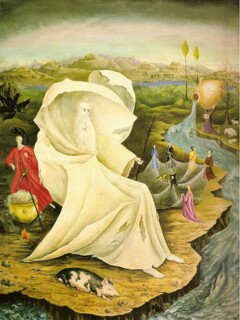

Domesticity in Carrington’s paintings and stories is the scene of Ovidian and spiritual transformations; cooking was a sort of alchemy, like painting, and she began increasingly to use egg tempera – influenced by paintings she had seen in Siena but also by its almost culinary processes (separating the egg yolk, adding wine or vinegar then water and pigment). She refused to explain her personal symbolism, but called reading The White Goddess ‘the greatest revelation of my life’. The figure of the muse, Robert Graves’s ‘Mother of all Living, the ancient power of fright and lust’, became less burdensome as manifested in The Giantess (c.1950), whose colossal central figure towers over the scene like a Madonna della Misericordia. She cradles an egg; geese fly out from beneath her pallium; her golden hair is a field of wheat. Around her feet a hunt is taking place – Uccello’s Hunt in the Forest but with a sylph instead of a stag – while the sea behind is teeming with boats, whales, crabs and bizarre creatures like monsters on a medieval map.

From 1950 the paintings become even more fantastical. Many are dominated by bald, spectral white figures: the Sidhe of Irish legends her grandmother told her. In Darvault (1950), Carrington’s two sons by Weisz, Pablo and Gabriel, stand in a de Chirico-esque courtyard, pale and cloaked with small plants growing from their heads. Is Carrington the feline figure in the apron with the elaborate white headdress and whiskers? In Down Below Carrington had described the worldview of her madness – ‘the father was the planet Cosmos, represented by the planet Saturn: the son was the Sun and I the Moon, an essential element of the Trinity, with a microscopic knowledge of the earth’ – and in Mexico she incorporated more and more elements of myth and occultism into her works; not just the Catholicism and Celtic stories of her childhood but astrological and Egyptian imagery, cabbala, Tibetan Buddhism, tarot.

‘In everybody, there is an inner bestiary,’ she claimed, and her pictures are overrun with animals and animal-headed creatures; sometimes sinister, sometimes acting as guides to the unconscious, as in The Pomps of the Subsoil (1947). As her interests grew more hermetic her paintings abandoned all trace of the world beyond. If the figures occupy any sort of space it’s rarely more than the planes of a room in muted browns or greys, and in many the surface is overlaid with geometric patterns that seem to imply some mystical framework. The canvas (or panel or board) is a decorative site where iconography is its own end: altars, eggs, rites, runes. Her stylised, amorphous figures, with their small feet, long fingers and broad childlike faces, are frozen in incomprehensible rituals; the paintwork is wispy, often transparent.

It’s a pity, because her best writing has a dryness that sets off absurdity nicely. The Hearing Trumpet, written in the early 1950s but only published thirty years later, makes having a fake log in your electric fire (an affectation of the 92-year-old narrator’s daughter-in-law) seem just as mad as the final rebirthing ritual that requires cooking yourself in a soup. Carrington’s gnomic comments about her life and work – ‘nothing is created by the imagination,’ ‘the egg is the macrocosm and the microcosm,’ ‘I am like a hyena, I get into the garbage cans’ – are surely mischievous, but in her paintings the comic element is often lost or seems closer to whimsy. Hairy monsters come out from under the table, knowing children peer round doors, a giant fairy-winged ermine is trapped by tiny huntsmen.

The Tate Liverpool show is redeemed by its variety: amassed from various private collections are drawings, etchings, textiles, costume, sculpture (sadly there is no catalogue). They show Carrington in collaboration with Leonor Fini, designing impossible hats, and posing for Kati Horna’s necrophilic photographs. She created costumes and sets for the Poesía en Voz Alta theatre group and for The Mansion of Madness (1973), a film based on Poe’s ‘System of Doctor Tarr and Professor Fether’, which is being shown in the exhibition. In more limited media her humour comes through again, her imagination is more accessible and her distinctive motifs – as in her Hunting Scene tapestry – don’t have to struggle under the weight of inscrutable meaning.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.